Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

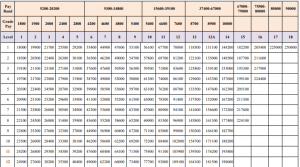

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

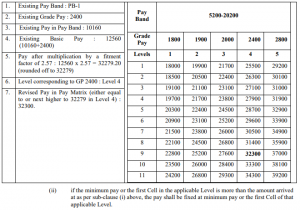

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

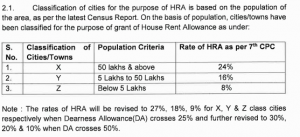

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

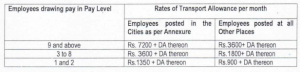

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Capital Punishment Jurisprudence in India: Recent Supreme Court Precedents Explained

Introduction

The Supreme Court of India has once again demonstrated the evolving capital punishment jurisprudence in India by commuting two death sentences to life imprisonment without remission in separate cases decided in July 2025. These landmark decisions by a bench comprising Justice Vikram Nath, Justice Sanjay Karol, and Justice Sandeep Mehta underscore the Court’s emphasis on considering mitigating circumstances, psychological factors, and social background studies in death penalty cases. The judgments mark a significant shift in capital punishment jurisprudence in India, moving beyond the mere brutality of crimes to examine the holistic circumstances surrounding both the offense and the offender.

Legal Framework Governing Death Penalty in India

Constitutional Provisions

The death penalty in India finds its constitutional foundation in Article 21 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to life and personal liberty. However, this right is not absolute and can be curtailed through a procedure established by law. The Constitution expressly recognizes capital punishment in Article 72, which empowers the President to grant pardons, reprieves, respites, or remissions of punishment, including death sentences [2].

Statutory Framework

The Indian Penal Code, 1860, under Section 302, prescribes punishment for murder as either death or imprisonment for life. The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, under Section 354(3), mandates that when a court sentences a person to death, it must state special reasons for such punishment in the judgment. This provision ensures that death sentences are not awarded arbitrarily and require specific justification based on the facts and circumstances of each case.

The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 (POCSO Act), under Section 6, provides for aggravated sexual assault on minors, which can attract capital punishment in the rarest of rare cases. This legislation was particularly relevant in one of the cases decided by the Supreme Court, where the convict was charged under POCSO provisions alongside the Indian Penal Code.

The ‘Rarest of Rare’ Doctrine

Evolution of the Doctrine

The ‘rarest of rare’ doctrine was established in the landmark case of Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab (1980), which laid down that death penalty should be awarded only in the rarest of rare cases when the alternative option is unquestionably foreclosed. The Supreme Court in Bachan Singh held that the death sentence should be imposed only when the crime is committed in an extremely brutal, grotesque, diabolical, revolting, or dastardly manner so as to arouse intense and extreme indignation of the community.

Modern Application

The recent judgments reflect a more nuanced application of the ‘rarest of rare’ doctrine, incorporating factors beyond the mere nature of the crime. The Court has emphasized that psychological analysis, social background studies, and mitigating circumstances must be thoroughly examined before imposing capital punishment. This approach aligns with the evolving international standards on human rights and the abolition of death penalty.

Analysis of Recent Supreme Court Decisions

Case 1: Karnataka Murder Case – Byluru Thippaiah

The first case involved Byluru Thippaiah, who was convicted for the brutal murder of his wife, sister-in-law, and three children in Karnataka in 2017. The convict believed that his wife had an immoral character and that the three children were born from such immoral activities. Both the trial court and the Karnataka High Court had sentenced him to death.

Mitigating Circumstances Considered

The Supreme Court examined several mitigating factors that were inadequately considered by the lower courts. The probation report revealed that Thippaiah had no criminal antecedents, and his conduct and behavioral report from prison authorities showed good moral character and excellent conduct with fellow prisoners and prison officials. Significantly, he had become literate while in prison through the Basic Literacy Program organized by the Zilla Lok Shiksha Samiti and had obtained a good rank [3].

Psychological Analysis

The Court noted that the convict had suffered from mental health struggles throughout his incarceration. He had attempted suicide on two occasions within jail – once upon learning about his family’s death and again when he was sentenced to death. The mitigation report revealed his troubled past, including lack of parental love, extreme insecurity following his brother’s death, school dropout, and depression following the breakdown of his first marriage.

Legal Reasoning

Justice Sanjay Karol, writing for the bench, observed that while the crime was of the most reprehensible nature, the sum total of circumstances that drove the appellant to commit the crime suggested that the death penalty might not be appropriate. The Court held that “considering the sum-total of circumstances that drove the appellant-convict to this point of committing this crime of a most reprehensible nature, the death penalty may not be appropriate.”

Case 2: Uttarakhand Rape and Murder Case – Jai Prakash

The second case involved Jai Prakash, who was convicted for the rape and murder of a minor girl in Dehradun in 2018. The convict had lured the child to his hut where she was raped and subsequently strangled to death. Both the trial court in 2019 and the Uttarakhand High Court in January 2020 had concurrently sentenced him to death.

Charges and Conviction

Jai Prakash was convicted under Sections 302 (murder), 201 (destruction of evidence), 376 (rape), and 377 (unnatural offences) of the Indian Penal Code, as well as Section 6 of the POCSO Act for aggravated sexual assault on a minor. The conviction was upheld by the Supreme Court, but the sentence was modified.

Mitigating Factors

The District Probation Officer’s report from Ayodhya revealed that the convict’s family condition was “very pathetic” as they earned their livelihood through manual labor. The psychological report indicated that he had not attended school due to poor socio-economic conditions at home and had been engaged in menial jobs to support his family from the tender age of 12 years. His conduct in jail was satisfactory, maintaining good relations with fellow inmates without any psychiatric disturbances.

Court’s Observation

Justice Karol observed that the lower courts had only commented on the brutality of the crime to justify the death penalty, without discussing other circumstances that would place the case in the ‘rarest of the rare’ category. The Court noted that “such an approach in our view cannot be sustained,” emphasizing that a holistic evaluation of both aggravating and mitigating circumstances is essential.

The Manoj vs State of MP Precedent

Background of the Case

The Supreme Court relied heavily on its 2023 decision in Manoj vs State of MP, which established crucial precedents for death penalty sentencing. This case involved a triple murder committed during a robbery, where the Court emphasized the need for courts to consider the entire background of facts and circumstances before sending a person to the “precipice of death” [4].

Key Principles Established

The Manoj case established several important principles for capital punishment jurisprudence:

- Comprehensive Background Study: Courts must conduct thorough social background studies and psychological analyses before imposing death sentences.

- Individualized Sentencing: Each case must be evaluated on its unique circumstances, focusing on both the crime and the criminal.

- Mitigation Evidence: Courts must actively seek and consider mitigation evidence, including the convict’s personal history, family background, and potential for rehabilitation.

- Procedural Safeguards: The judgment emphasized the need for proper procedural safeguards to prevent arbitrary imposition of death sentences.

Regulatory Framework and Procedural Safeguards

Mandatory Requirements

The Supreme Court has established several mandatory requirements for death penalty cases:

- Special Reasons: Under Section 354(3) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, courts must provide special reasons for awarding death sentences.

- Confirmation by High Court: All death sentences must be confirmed by the High Court under Section 366 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

- Mitigating Circumstances: Courts must examine all mitigating circumstances, including the convict’s background, mental state, and potential for rehabilitation.

Social Background Studies

The Court has emphasized the importance of comprehensive social background studies in death penalty cases. These studies should include:

- Family history and socio-economic background

- Educational background and employment history

- Mental health assessment and psychological evaluation

- Criminal antecedents and character assessment

- Conduct in prison and potential for reformation

International Perspective and Human Rights Considerations

Global Trend Towards Abolition

The Supreme Court’s approach reflects the global trend towards abolition of the death penalty. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which India is a signatory, encourages the abolition of capital punishment and restricts its application to the most serious crimes.

Safeguards and Guarantees

The United Nations Economic and Social Council has established safeguards guaranteeing protection of the rights of those facing the death penalty, including:

- Restriction to the most serious crimes

- Exclusion of persons under 18 years of age

- Prohibition of execution of pregnant women

- Right to seek pardon or commutation

- Adequate legal representation

Impact on Indian Criminal Justice System

Precedents in Capital Punishment Jurisprudence

These recent decisions create important precedents for lower courts in death penalty cases. The emphasis on psychological analysis and social background studies will likely influence future capital punishment jurisprudence across Indian courts.

Prison Reforms

The Court’s consideration of prison conduct and rehabilitation potential highlights the importance of prison reforms and educational programs for convicts. The case of Byluru Thippaiah, who became literate in prison, demonstrates the potential for reformation even in serious criminal cases.

Legal Practice in Capital Punishment

The judgments will likely influence legal practice in capital punishment cases, with defense lawyers placing greater emphasis on mitigation evidence and comprehensive background studies. Prosecutors will need to establish not only the brutality of the crime but also the absence of mitigating circumstances.

Challenges and Future Directions

Implementation Challenges

While the Supreme Court has established clear guidelines, implementation at the trial court level remains challenging. Many trial courts lack the resources and expertise to conduct comprehensive psychological evaluations and social background studies.

Need for Specialized Training

There is a pressing need for specialized training for judges, prosecutors, and defense lawyers in capital punishment cases. This training should focus on identifying and evaluating mitigating circumstances, understanding psychological factors, and conducting proper social background studies.

Infrastructure Development

The criminal justice system requires infrastructure development to support comprehensive evaluation in death penalty cases. This includes establishing specialized units for psychological evaluation, social work departments for background studies, and proper documentation systems.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s recent decisions in commuting death sentences to life imprisonment represent a significant evolution in Indian capital punishment jurisprudence. By emphasizing the importance of psychological analysis, social background studies, and comprehensive evaluation of mitigating circumstances, the Court has moved beyond a purely retributive approach to criminal justice.

These judgments underscore the principle that the death penalty should truly be reserved for the rarest of rare cases, where not only the crime is exceptionally heinous but also where there are no mitigating circumstances that could justify a lesser punishment. The Court’s approach reflects a more humane and scientifically informed understanding of criminal behavior and the factors that contribute to criminal conduct.

The decisions also highlight the importance of proper procedural safeguards in capital punishment jurisprudence and the need for courts to look beyond the immediate circumstances of the crime to understand the broader context in which it was committed. This holistic approach to criminal justice is essential for ensuring that the death penalty, if retained, is applied fairly and consistently.

As India continues to grapple with the question of capital punishment, these judgments provide valuable guidance for maintaining the delicate balance between protecting society from the most serious crimes and ensuring that the ultimate punishment is imposed only after the most careful consideration of all relevant factors. The emphasis on rehabilitation potential and the possibility of reformation also reflects a more progressive approach to criminal justice that prioritizes human dignity and the potential for redemption.

References

[1] Verdictum. (2025). “He Should Spend His Days In Jail Attempting To Repent For The Crimes: Supreme Court Commutes Death Sentence Of Man Who Killed Wife & Children.” Available at: https://www.verdictum.in/court-updates/supreme-court/byluru-thippaiah-byaluru-thippaiah-nayakara-thippaia-v-state-of-karnataka-2025-insc-862-commutes-death-sentence-jail-repent-crimes-killing-wife-children-1585117

[2] Constitution of India, Article 21 and Article 72. Available at: https://www.india.gov.in/my-government/constitution-india

[3] LiveLaw. (2025). “Supreme Court Commutes Death Penalty Of Man Convicted For Rape-Murder Of 10 Yr Old Girl To Life Term Without Remission.” Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/supreme-court/supreme-court-commutes-death-penalty-of-man-convicted-for-rape-murder-of-10-yr-old-girl-to-life-term-without-remission-297950

[4] Indian Kanoon. (2023). “Manoj Kumar Soni vs The State Of M.P. on 11 August, 2023.” Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/167720008/

[5] Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab, (1980) 2 SCC 684

[6] SCCOnline. (2023). “Supreme Court, in a balancing act, commutes Death Sentence to 20 Years Imprisonment in Indiscriminate Firing case that killed 6.” Available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2023/11/14/supreme-court-commutes-death-sentence-to-20-years-imprisonment-in-indiscriminate-firing-case-legal-news/

The Enforcement Directorate’s Coercive Actions and Their Impact on Economic Growth: A Critical Analysis

Introduction

The Enforcement Directorate’s recent summoning of industrialist Anil Ambani highlights a concerning pattern in India’s approach to financial crime enforcement that warrants critical examination. While the Enforcement Directorate plays a crucial role in combating money laundering and economic offenses, its reliance on coercive powers such as personal summons, arrests, and asset attachments raises serious questions about proportionality, due process, and the broader impact on economic growth.

The Economic Growth Engine Under Threat

Industrialists as Economic Catalysts

India’s industrialists serve as the primary engines of economic growth, mobilizing human capital on a massive scale and channeling it toward productive activities[1]. They create employment, drive innovation, generate tax revenue, and contribute significantly to GDP growth. Business confidence is directly correlated with economic performance – research shows that a one percent increase in business confidence can lead to a 0.23 percent increase in economic growth[2]. When enforcement agencies target these key economic actors through harsh coercive measures, they risk undermining the very foundation of economic progress.

The Confidence Crisis

The ED’s enforcement approach is creating a climate of fear among business leaders that extends far beyond those directly investigated. Fitch Ratings has explicitly warned that Enforcement Directorate searches at corporate premises “may tarnish business prospects and constrict funding access due to reduced market confidence”[3]. This reputational damage occurs “even if no wrongdoing is identified,” highlighting the disproportionate impact of the current enforcement methodology.

The FICCI Business Confidence Survey demonstrates how quickly business sentiment can deteriorate – the Overall Business Confidence Index has shown significant volatility in response to regulatory actions and enforcement activities[4]. When confidence drops, investment follows suit, creating a cascading effect on employment and economic growth.

The Coercive Power Problem

Gunboat Bureaucracy in Action

The ED’s current approach exemplifies what can be termed “gunboat bureaucracy” – the use of overwhelming state power to achieve compliance through fear rather than cooperation. Research on coercive power demonstrates that while it may yield short-term compliance, it “increases an antagonistic climate and enforced compliance” while undermining long-term cooperation[5].

The Supreme Court has already criticized the Enforcement Directorate for “crossing all limits” and “violating the federal structure” in some of its enforcement actions[6]. This judicial pushback reflects growing concern about the agency’s overreach and its impact on constitutional principles.

The Arrest-First, Question-Later Approach

The ED’s practice of personal summons followed by potential arrest creates an inherently coercive environment. Unlike civil enforcement mechanisms, criminal enforcement carries the threat of imprisonment, which fundamentally alters the power dynamic between the state and business leaders. This approach prioritizes punishment over prevention and compliance, contrary to modern enforcement best practices.

International evidence suggests that “private tools are more effective than public forms of enforcement” in developing economies like India[7]. The current emphasis on criminal enforcement over administrative remedies represents a regressive approach that may actually reduce overall compliance effectiveness.

Due Process Deficits

The Case for Legal Representation

Modern due process principles recognize that complex financial investigations require sophisticated legal expertise. Allowing legal representation during the summoning and questioning process would not undermine the ED’s investigative capabilities but would ensure that proceedings are conducted fairly and efficiently.

The current practice of personal summons without adequate provisions for legal representation violates basic principles of natural justice. As established in Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, any procedure affecting life or liberty must be “just, fair, and reasonable”[8]. The ED’s approach falls short of this constitutional standard.

Alternatives to Coercive Enforcement

Several alternatives could achieve the ED’s legitimate objectives without resorting to coercive measures:

- Administrative Enforcement: Many regulatory violations can be addressed through administrative penalties and compliance orders rather than criminal prosecution.

- Voluntary Disclosure Programs: Incentivizing self-reporting and cooperation through reduced penalties could improve compliance while preserving business relationships.

- Civil Recovery Mechanisms: Asset recovery through civil proceedings would be less disruptive to business operations while still addressing economic losses.

- Regulatory Settlements: Negotiated settlements with compliance monitors could ensure future adherence to regulations without the stigma of criminal prosecution.

International Best Practices

Proportionate Enforcement Models

The OECD emphasizes that “enforcement needs to be risk-based and proportionate: the frequency of inspections and the resources employed should be proportional to the level of risk”[9]. This principle suggests that the ED should reserve its most coercive powers for cases involving the highest risk to the financial system.

Countries with successful enforcement regimes emphasize graduated responses, using criminal enforcement only as a last resort for the most egregious violations. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, for instance, employs a range of enforcement tools from warning letters to civil penalties before resorting to criminal referrals[10].

Corporate Governance Solutions

Rather than relying primarily on punitive enforcement, India should strengthen corporate governance mechanisms that prevent violations before they occur. Research shows that “good corporate governance practices will detect and prevent fraud and corruption”[11]. Investing in preventive measures would be more cost-effective than reactive enforcement.

The Constitutional Dimension

Fundamental Rights at Stake

The current enforcement approach raises serious constitutional concerns about the fundamental rights of business leaders. The right to carry on business under Article 19(1)(g) includes protection from arbitrary state interference. The ED’s broad use of coercive powers may violate this fundamental right, particularly when applied without sufficient procedural safeguards.

Federalism and Separation of Powers

The Supreme Court’s criticism of the Enforcement Directorate for “violating the federal structure” points to broader constitutional concerns[6]. When federal agencies overstep their bounds in pursuit of enforcement objectives, they undermine the delicate balance of power that underpins India’s democratic system.

Economic Impact Assessment

Quantifying the Costs

While precise figures are difficult to obtain, the economic costs of the current enforcement approach are substantial:

- Business Confidence: Declining confidence translates directly into reduced investment and slower economic growth[2][12].

- Compliance Costs: Businesses must invest heavily in legal defense and compliance systems to protect against enforcement actions.

- Opportunity Costs: Resources diverted to enforcement proceedings are unavailable for productive economic activities.

- International Perception: Harsh enforcement creates negative perceptions among foreign investors, potentially reducing FDI inflows[13].

The Growth Opportunity Cost

India’s bureaucratic inefficiencies already rank among the world’s worst, with the country scoring 9.41 out of 10 on bureaucratic burden measures[14]. Adding aggressive enforcement to this existing burden creates a compound negative effect on economic growth potential.

Reform Recommendations

Immediate Reforms

- Legal Representation Rights: Guarantee the right to legal counsel during all Enforcement Directorate proceedings.

- Graduated Enforcement: Implement a tiered approach with administrative remedies preceding criminal enforcement.

- Transparency Requirements: Publish clear guidelines on when criminal enforcement will be pursued versus administrative remedies.

- Appeals Process: Create an independent review mechanism for enforcement decisions.

Structural Changes

- Specialized Courts: Establish fast-track commercial courts for financial crime cases to reduce delays and uncertainty.

- Alternative Dispute Resolution: Develop arbitration and mediation mechanisms for regulatory disputes.

- Compliance Incentives: Create safe harbor provisions for businesses that maintain robust compliance programs.

- International Cooperation: Align enforcement practices with international best practices and mutual legal assistance treaties.

Conclusion: Balancing Enforcement and Growth

The challenge facing India is to maintain effective enforcement of financial laws while preserving the business environment necessary for economic growth. The current approach of coercive enforcement may satisfy short-term political objectives but risks long-term economic damage.

A reformed enforcement system would recognize that industrialists are partners in economic development, not adversaries to be subdued. By adopting proportionate enforcement measures, respecting due process rights, and emphasizing prevention over punishment, India can maintain regulatory integrity while fostering the business confidence necessary for sustained economic growth.

The ED’s role should evolve from that of an enforcement hammer to that of a regulatory partner, working with business leaders to build a transparent, compliant financial system. This transformation is not just desirable but essential if India is to achieve its economic growth aspirations while maintaining the rule of law and constitutional governance that underpin democratic society.

The path forward requires courage to reform entrenched practices, wisdom to balance competing interests, and commitment to the constitutional principles that make India a democracy rather than an autocracy. The stakes could not be higher – India’s economic future hangs in the balance.

References

[1] Enforcement Directorate (ED): Structure, Jurisdiction, and Impact on … https://blog.upscgeeks.in/blog/general-studies-II/polity/enforcement-directorate-structure-jurisdiction-impact

[2] [PDF] 115 an econometric analysis on the impact of business confidence … https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/889962

[3] ED’s searches at corporates may tarnish business prospects … https://economictimes.com/industry/banking/finance/banking/eds-searches-at-corporates-may-tarnish-business-prospects-constrict-funding-access-fitch/articleshow/100121230.cms

[4] [PDF] ficci business confidence survey https://ficci.in/public/storage/SEDocument/20267/FICCI_Voice_SGs%20Desk.pdf

[5] Authorities’ Coercive and Legitimate Power: The Impact on … https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5241301/

[6] As SC raps ED, a look at agency’s powers, role and red lines https://indianexpress.com/article/upsc-current-affairs/upsc-essentials/sc-pulls-up-ed-what-are-the-powers-of-indias-financial-crime-watchdog-10044091/

[7] [PDF] Corporate Governance and Enforcement – CiteSeerX https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=9258a5b2302fc042db545e821d900708139347ec

[8] The Curious Case of ‘Due Process’ in the Indian Constitution https://www.theindiaforum.in/law/curious-case-due-process-indian-constitution

[9] [PDF] Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections (EN) – OECD https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2014/05/regulatory-enforcement-and-inspections_g1g3b1b4/9789264208117-en.pdf

[10] Protecting Everyday Investors and Preserving Market Integrity https://www.sec.gov/newsroom/speeches-statements/avakian-protecting-everyday-investors-091720

[11] How corporate governance can prevent fraud and corruption | CGI https://www.thecorporategovernanceinstitute.com/insights/guides/how-corporate-governance-can-prevent-fraud-and-corruption/

[12] The Role of the Business Climate Index in Economic Forecasting https://www.worldgovernmentssummit.org/observer/reports/detail/assessing-business-confidence-the-role-of-the-business-climate-index-in-economic-forecasting

[13] [PDF] The Economic Impact of White Collar Crime on India’s Growth https://www.ijarsct.co.in/Paper24883.pdf

[14] India’s bureaucracy is ‘the most stifling in the world’ – BBC News https://www.bbc.com/news/10227680

Article 142 Under Scrutiny: Supreme Court’s Rare Self-Correction in the BPSL Case

Introduction

In an extraordinary demonstration of judicial accountability, Chief Justice B.R. Gavai recently acknowledged that the Supreme Court’s invocation of Article 142 in a corporate insolvency case “resulted in injustice” rather than delivering complete justice.[1]This admission, coupled with the Court’s decision to recall its own judgment in the Bhushan Power and Steel Limited (BPSL) case, has reignited the debate over the proper scope and application of Article 142 of the Constitution.

The Constitutional Provision at the Center of Controversy

Article 142 empowers the Supreme Court to “pass such decree or make such order as is necessary for doing complete justice in any cause or matter pending before it”.[2] Originally conceived as an extraordinary remedy to fill gaps where laws are silent or justice would otherwise be denied, this provision has increasingly become a subject of intense constitutional debate.[3]

The Growing Criticism

The provision gained unprecedented attention when Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar characterized Article 142 as a “nuclear missile against democratic forces available to the judiciary 24×7”.[4] This criticism emerged particularly after the Supreme Court’s April 8, 2025 judgment in the Tamil Nadu Governor case, where Justices J.B. Pardiwala and R. Mahadevan invoked Article 142 to grant “deemed assent” to bills that had been indefinitely delayed by the Governor.[5]

The BPSL Case: From Resolution to Liquidation to Recall

The Original Crisis

The Bhushan Power and Steel Limited case exemplifies the complexities surrounding Article 142’s application. In May 2025, a bench comprising Justice Bela M. Trivedi (now retired) and Justice Satish Chandra Sharma rejected JSW Steel’s ₹19,700 crore resolution plan for BPSL and ordered the company’s liquidation.[6] The Court found multiple procedural violations, including:

- JSW Steel’s failure to comply with statutory timelines for over two years

- Inappropriate funding structure combining equity and optionally convertible debentures

- The Resolution Professional’s failure to discharge duties under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code[7]

- The Committee of Creditors’ alleged failure to exercise proper commercial wisdom[8]

The Human Cost

The liquidation order threatened the livelihoods of approximately 25,000 workers and put at risk JSW Steel’s investment of nearly ₹20,000 crore in reviving the company. This stark human dimension became central to CJI Gavai’s subsequent analysis of the case.[6]

The Unprecedented Recall

On July 31, 2025, in a rare exercise of judicial introspection, CJI B.R. Gavai and Justice Satish Chandra Sharma recalled the May 2 judgment. The Chief Justice’s observations were particularly striking:[6]

“Prima facie, we are of the view that the impugned judgment does not correctly consider the legal position as has been laid down by a catena of judgments… 25,000 people cannot be thrown onto the road. Article 142 has to be utilised to do complete justice, not to do injustice to 25,000 workers”.

Legal Precedents and Commercial Wisdom

The Doctrine of Commercial Wisdom

The BPSL case highlights the tension between judicial review and the well-established doctrine of commercial wisdom under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code. The Supreme Court has consistently held in cases like K. Sashidhar v. Indian Overseas Bank (2019) that courts cannot interfere with the commercial decisions of the Committee of Creditors once a resolution plan is approved by the requisite majority.[9]

The limited judicial review under Section 30(2) of the IBC is restricted to ensuring that resolution plans do not contravene statutory provisions and conform to regulatory requirements.[10] As the Court noted in multiple precedents, “the adjudicating authority cannot interfere on merits with the commercial decision taken by the Committee of Creditors”.

Procedural vs. Substantive Review

The BPSL judgment’s recall raises fundamental questions about the boundaries of judicial intervention. While the original May 2025 judgment criticized procedural lapses, the recall suggests that such technical violations may not justify setting aside an otherwise successful resolution plan that has created substantial value and employment.[11]

The Presidential Reference and Constitutional Questions

The Tamil Nadu Governor case has prompted President Droupadi Murmu to invoke Article 143 of the Constitution, seeking the Supreme Court’s advisory opinion on 14 crucial questions.[12] The Presidential Reference, scheduled for hearing from August 19, 2025, will examine whether:

- Courts can impose timelines on constitutional authorities like the President and Governors

- Article 142 can substitute constitutional powers of executive authorities[13]

- The concept of “deemed assent” violates the doctrine of separation of powes[14]

Implications for Legal Practice

Constitutional Law

The BPSL case demonstrates both the power and the perils of Article 142. While the provision serves as a crucial tool for ensuring justice where traditional remedies fall short, its application requires careful consideration of constitutional boundaries and practical consequences. The Court’s self-correction mechanism, though rare, shows the judiciary’s capacity for introspection and course correction.

Corporate Law and Insolvency Practice

For practitioners in corporate law and insolvency, the BPSL case offers several important lessons:

- Timeline Compliance: While the IBC emphasizes time-bound resolution, courts may consider the practical realities of complex corporate restructuring[6]

- Commercial Wisdom Doctrine: The recall reinforces that judicial interference with creditor decisions should be minimal, particularly when resolution plans have been successfully implemented[7]

- Finality vs. Accountability: The case raises questions about the finality of insolvency proceedings and the circumstances under which implemented resolution plans can be challenged[15]

Procedural Safeguards

The judgment recall also highlights the importance of comprehensive judicial review at all levels. The case suggests that when fundamental procedural requirements are met and commercial wisdom has been exercised, courts should be cautious about invoking extraordinary powers like Article 142 to overturn business decisions.[11]

Looking Forward: Balancing Justice and Institutional Integrity

The BPSL case represents a watershed moment in Indian constitutional jurisprudence. CJI Gavai’s acknowledgment that Article 142 was misused to cause injustice rather than deliver complete justice sets an important precedent for judicial accountability. This self-correction mechanism, while creating short-term uncertainty, ultimately strengthens institutional integrity and public confidence in the judiciary.

The upcoming Presidential Reference hearings will likely provide much-needed clarity on the scope and limitations of Article 142. As legal practitioners, understanding these evolving boundaries will be crucial for advising clients on matters involving extraordinary judicial remedies.

The case also underscores the human dimension of legal decisions. With 25,000 jobs and thousands of crores in investments at stake, the Court’s eventual recognition that “ground realities” must inform judicial decision-making reflects a mature understanding of law’s practical impact on society.

As the legal community awaits the August 7, 2025 fresh hearing of the BPSL case and the broader constitutional questions to be addressed in the Presidential Reference, one thing remains clear: the balance between judicial activism and restraint continues to evolve, shaped by the practical consequences of constitutional interpretation in India’s complex legal landscape.

References

[1] CJI Gavai Recalls May 2 Verdict That Ordered Liquidation of Bhushan Power & Steel Available at: https://lawchakra.in/supreme-court/verdict-liquidation-bhushan-power-steel/

[2] Article 142 of the Constitution of India Available at: https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/to-the-point/ttp-constitution-of-india/article-142-of-the-constitution-of-india

[3] Article 142: The Supreme Power or Judicial Overreach? Available at: https://ddnews.gov.in/en/article-142-the-supreme-power-or-judicial-overreach/

[4] Has the Supreme Court been trigger-happy with Article 142?

Available at: https://www.scobserver.in/journal/has-the-supreme-court-been-trigger-happy-with-article-142/

[5] Pendency of bills before Tamil Nadu Governor | Judgement Summary Available at: https://www.scobserver.in/reports/pendency-of-bills-before-tamil-nadu-governor-judgement-summary/

[6] SC withdraws Bhushan Power liquidation order, review hearing on Aug 7 Available at: https://www.business-standard.com/industry/news/sc-recalls-judgement-jsw-resolution-plan-bhushan-power-liquidation-125073101593_1.html

[7] ‘Bhushan Steel’ Judgement: Commercial wisdom sidelined in favour of narrow procedural view Available at: https://www.scobserver.in/journal/bhushan-steel-judgement-commercial-wisdom-sidelined-in-favour-of-narrow-procedural-view/

[8] Commercial Wisdom vs Judicial Review: The Supreme Court’s BPSL Verdict and the Future of IBC Available at: https://nliulawreview.nliu.ac.in/blog/commercial-wisdom-vs-judicial-review-the-supreme-courts-bpsl-verdict-and-the-future-of-ibc/

[9] IN THE NATIONAL COMPANY LAW TRIBUNAL DIVISION BENCH – II, CHENNAI Available at: https://nclt.gov.in/gen_pdf.php?filepath=%2FEfile_Document%2Fncltdoc%2Fcasedoc%2F3305118003002019%2F04%2FOrder-Challenge%2F04_order-Challange_004_1712057631850786731660bed1f10fad.pdf

[10]’ JUDICIAL REVIEW ON COMMERCIAL WISDOM OF COMMITTEE OF CREDITORS IN RESPECT OF APPROVED RESOLUTION PLAN Available at: https://www.taxtmi.com/article/detailed?id=14757

[11] SC Recalls Bhushan Power Liquidation Judgment, Admits JSW’s Review Petition Available at: https://www.outlookbusiness.com/corporate/sc-recalls-bhushan-power-liquidation-judgment-admits-jsws-petition

[12] Presidential Reference: Can the Supreme Court Clarify Past Rulings? Available at: https://vajiramandravi.com/current-affairs/presidential-reference-can-the-supreme-court-clarify-past-rulings

[13] Presidential Reference concerns all States, will answer all questions raised: Supreme Court avaialble at: https://www.cdjlawjournal.com/long.php?id=5018

[14] SC fixes Presidential Reference hearing from August 19, to first hear Tamil Nadu and Kerala on maintainability Available at: https://theleaflet.in/leaflet-reports/sc-fixes-presidential-reference-hearing-from-august-19-to-first-hear-tamil-nadu-and-kerala-on-maintainability

[15] Rejection of Resolution Plan: Review of Judgment? Available at : https://indiacorplaw.in/2025/06/19/rejection-of-resolution-plan-review-of-judgment/

Supreme Court’s Historic Ruling on Tribal Women’s Inheritance Rights: A Landmark Victory for Gender Equality

Introduction

The Supreme Court of India delivered a groundbreaking judgment on July 17, 2025, that fundamentally transformed the inheritance rights landscape for tribal women across the country. The bench comprising Justice Sanjay Karol and Justice Joymalya Bagchi ruled that tribal women and their legal heirs are entitled to equal shares in ancestral property, marking a watershed moment in India’s journey toward gender equality and constitutional justice [1]. This judgment is now being seen as a turning point in the legal recognition of tribal women’s inheritance rights in India, addressing a long-standing gap in the country’s property and succession laws. The case emerged from a dispute involving Dhaiya, a tribal woman whose children sought equal inheritance rights in their maternal grandfather’s property. The ruling not only resolved the individual grievance but also established a broader precedent that challenges patriarchal customs and affirms the constitutional principles of equality and non-discrimination.

Background and Legal Context

The Case of Dhaiya and the Genesis of the Judgment

The case that led to this historic ruling originated when Dhaiya’s children, representing her legal heirs, approached the Supreme Court seeking equal inheritance rights in ancestral property. The family’s male heirs had categorically denied this claim, citing customary practices that excluded women from succession and inheritance rights within their tribal community.

Dhaiya’s legal journey began in lower courts, where her plea for equal inheritance rights was consistently rejected. Two lower courts had denied her petition, requiring her to prove the existence of a custom that would allow women to inherit property rather than placing the burden on male heirs to demonstrate the legal validity of exclusionary practices. This flawed approach in the lower courts became a central point of criticism in the Supreme Court’s eventual judgment.

The Supreme Court’s intervention became necessary when it became apparent that the lower courts had fundamentally misapplied the burden of proof. The apex court recognized that requiring a woman to prove her right to inherit, rather than requiring those who sought to exclude her to justify such exclusion, violated basic principles of justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution.

Constitutional Framework and Legal Principles

The Supreme Court’s judgment was anchored in fundamental constitutional principles, particularly Article 14 and Article 15 of the Indian Constitution. Article 14 guarantees equality before the law and equal protection of laws to all persons within the territory of India. Article 15 specifically prohibits discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth [2].

The court’s opening observation captured the essence of the constitutional imperative: “One would think that in this day and age, where great strides have been made in realising the constitutional goal of equality, this Court would not need to intervene for equality between the successors of a common ancestor, and the same should be a given, irrespective of their biological differences… but it is not so.”

This statement reflects the court’s recognition that despite decades of constitutional governance and legal reform, gender-based discrimination in inheritance matters persists, particularly within marginalized communities like Scheduled Tribes. The judgment emphasizes that constitutional principles must prevail over discriminatory customs, regardless of their historical or cultural significance.

The Hindu Succession Act and Tribal Communities

Statutory Framework and Exemptions

The Hindu Succession Act, 1956, serves as the primary legislation governing inheritance rights for Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs in India. However, Section 2(2) of the Act specifically exempts Scheduled Tribes from its purview unless the Central Government directs otherwise through official notification [3]. This exemption was designed to preserve tribal autonomy and protect customary laws that govern tribal communities.

The statutory exemption reads: “Sub-section (2) of Section 2 of the Hindu Succession Act significantly provides that nothing contained in the Act shall apply to the members of any Scheduled Tribe within the meaning of clause (25) of Article 366 of the Constitution unless otherwise directed by the Central Government by means of a notification in the Official Gazette.”

This exemption was affirmed by the Supreme Court in its 1996 judgment in Madhu Kishwar versus State of Bihar, which recognized the special constitutional status of tribal communities and their right to be governed by customary laws in matters of personal law, including succession and inheritance [4].

Implications of the Exemption

The exemption of Scheduled Tribes from the Hindu Succession Act created a legal vacuum that often worked to the disadvantage of tribal women. While the Act, particularly after its 2005 amendment, granted equal inheritance rights to daughters and sons in Hindu families, tribal women remained subject to customary laws that frequently discriminated against them.

The Supreme Court in the current judgment acknowledged this disparity while emphasizing that exemption from the Hindu Succession Act could not automatically deprive tribal women of their inheritance rights. The court stated that the exemption was meant to preserve tribal autonomy, not to perpetuate gender-based discrimination that violates constitutional principles.

Legal Analysis and Judicial Reasoning

Application of Justice, Equity, and Good Conscience

The Supreme Court’s judgment extensively relied on the principle of “justice, equity, and good conscience,” a fundamental tenet of Indian jurisprudence that guides courts when statutory law provides inadequate guidance. Justice Karol, writing for the bench, emphasized that courts must exercise these principles when confronted with customs that deny women their rightful inheritance.

The court observed: “When applying the principle of justice, equity and good conscience, the courts have to be vigilant in ensuring that discrimination against women is not perpetuated under the garb of customs or traditions.” This principle becomes particularly relevant in cases involving tribal communities where customary laws may conflict with constitutional guarantees of equality.

The application of justice, equity, and good conscience in this context serves as a bridge between constitutional principles and customary practices. The court recognized that while customs deserve respect and protection, they cannot be used as shields to perpetuate discrimination that violates fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution.

Burden of Proof and Evidentiary Standards

One of the most significant aspects of the Supreme Court’s judgment was its critique of the evidentiary burden placed on Dhaiya by the lower courts. The Supreme Court noted that the lower courts had erroneously required Dhaiya to prove the existence of a custom allowing women to inherit, rather than requiring the male heirs to demonstrate the legal validity of exclusionary practices.

The court established that when inheritance rights are disputed, the burden of proof should not fall on those seeking equal treatment but rather on those who claim the right to exclude others based on discriminatory customs. This shift in evidentiary burden represents a significant advancement in protecting the rights of marginalized individuals within tribal communities.

The judgment states: “The Supreme Court acknowledged Dhaiya had been unable to establish a custom of female succession, but said it was equally true that no custom to the contrary could be proved.” This observation highlights the court’s recognition that the absence of evidence supporting women’s inheritance rights does not automatically validate discriminatory practices.

Evolution of Customs and Legal Adaptation

The Supreme Court’s judgment contains a profound observation about the evolutionary nature of customs and their relationship with contemporary legal principles. Justice Karol noted: “Like law, customs also cannot be bound by time. Others cannot be allowed to take refuge in customs or hide behind them to deprive others of their rights.”

This statement reflects the court’s understanding that customs, while deserving of respect, must adapt to changing social and legal realities. The judgment emphasizes that customs that perpetuate discrimination cannot claim immunity from constitutional scrutiny simply because of their historical prevalence.

The court’s approach represents a balanced perspective that respects cultural diversity while ensuring that cultural practices conform to constitutional principles. This balance is particularly important in the context of tribal communities, where the tension between tradition and modernity often manifests in legal disputes over inheritance rights.

Regulatory Framework and Implementation

Central Government’s Role and Notification Powers

The Supreme Court’s judgment implicitly calls for greater Central Government involvement in regulating inheritance rights within tribal communities. Under Section 2(2) of the Hindu Succession Act, the Central Government possesses the power to extend the Act’s provisions to Scheduled Tribes through official notifications.

The court’s judgment suggests that the Central Government should consider exercising this power to ensure that tribal women receive equal inheritance rights. Such notifications would provide a statutory framework for inheritance rights while respecting the autonomy of tribal communities to maintain their cultural practices in other areas.

The regulatory framework would need to balance several competing interests: constitutional guarantees of equality, tribal autonomy protected under various constitutional provisions, and the practical realities of implementing uniform inheritance laws across diverse tribal communities with varying customs and practices.

State-Level Implementation and Monitoring

The implementation of the Supreme Court’s judgment requires coordinated efforts at both central and state levels. State governments, particularly those with significant tribal populations, must ensure that local courts and administrative officials understand and implement the new legal standard established by the Supreme Court.

State-level implementation would involve training judicial officers, revenue officials, and other administrators who deal with inheritance disputes in tribal areas. Additionally, legal aid programs would need to be strengthened to ensure that tribal women can access the legal system to enforce their newly recognized rights.

The regulatory framework must also address practical challenges such as documentation of property ownership, resolution of existing disputes, and prevention of future discrimination. These challenges require a comprehensive approach that combines legal reform with social awareness programs and institutional capacity building.

Impact on Gender Equality and Social Justice

Transformative Potential of the Judgment

The Supreme Court’s ruling represents more than a legal victory; it embodies a transformative potential that could reshape gender relations within tribal communities across India. By establishing tribal women’s inheritance rights, the judgment challenges deeply entrenched patriarchal structures that have historically marginalized women within these communities.

The transformative impact extends beyond individual cases to encompass broader social change. When women possess equal inheritance rights, they gain economic independence and social status that can positively influence their roles within families and communities. This economic empowerment can lead to improved decision-making power, better access to education and healthcare, and enhanced overall quality of life.

The judgment also sends a powerful message about the universality of constitutional principles. It demonstrates that equality and non-discrimination are not merely aspirational goals but enforceable rights that apply to all citizens, regardless of their community affiliation or cultural background.

Addressing Historical Injustices

The Supreme Court’s judgment represents a significant step toward addressing historical injustices faced by tribal women. For generations, these women have been denied equal inheritance rights based on customs that reflected patriarchal power structures rather than legitimate cultural practices.

The court’s recognition of tribal women’s inheritance rights acknowledges that gender equality is not a modern Western concept imposed on traditional societies but rather a fundamental human right that transcends cultural boundaries. This recognition helps correct historical narratives that have portrayed gender discrimination as an integral part of tribal culture.

The judgment also provides a foundation for addressing other forms of gender-based discrimination within tribal communities. By establishing that customs cannot override constitutional principles, the court has created a legal framework that can be applied to other areas where tribal women face discrimination.

Comparative Analysis with Other Inheritance Laws

Hindu Succession Act Amendments and Their Impact

The 2005 amendment to the Hindu Succession Act granted daughters equal inheritance rights with sons in Hindu families, representing a significant advancement in women’s property rights. However, the exemption of Scheduled Tribes from the Act’s purview meant that tribal women did not automatically benefit from these progressive changes.

The Supreme Court’s current judgment effectively extends the spirit of the 2005 amendment to tribal communities, ensuring that tribal women receive similar protection against inheritance discrimination. This extension is achieved not through direct application of the Hindu Succession Act but through constitutional principles that mandate equal treatment.

The comparative analysis reveals that while Hindu women gained statutory protection against inheritance discrimination through legislative amendment, tribal women have achieved similar protection through judicial interpretation of constitutional principles. This difference in approach reflects the complex relationship between statutory law, customary practices, and constitutional guarantees in India’s diverse legal landscape.

International Human Rights Standards

The Supreme Court’s judgment aligns with international human rights standards that recognize women’s equal inheritance rights as fundamental human rights. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), to which India is a signatory, specifically addresses inheritance discrimination and requires states to ensure equal rights for women in property matters [5].

The judgment demonstrates India’s commitment to international human rights obligations while respecting cultural diversity. By grounding its decision in constitutional principles rather than imposing external standards, the court has achieved compliance with international norms while maintaining the legitimacy of its ruling within the Indian legal system.

Challenges and Future Implications

Implementation Challenges

Despite the Supreme Court’s clear ruling, implementation of tribal women’s inheritance rights faces several practical challenges. These challenges include resistance from traditional power structures within tribal communities, lack of awareness about legal rights among tribal women, and inadequate legal infrastructure in remote tribal areas.

The implementation process must address these challenges through comprehensive strategies that combine legal reform with social awareness programs. Legal aid organizations, women’s rights groups, and tribal welfare departments must work together to ensure that the court’s ruling translates into practical benefits for tribal women.

Documentation and proof of inheritance claims present additional challenges in tribal areas where formal property records may be incomplete or non-existent. The implementation framework must address these documentation challenges while ensuring that procedural requirements do not become barriers to accessing inheritance rights.

Future Legal Developments

The Supreme Court’s judgment is likely to influence future legal developments in several related areas. Courts may apply similar reasoning to other forms of gender-based discrimination within tribal communities, potentially leading to broader reforms in tribal personal laws.

The judgment may also prompt legislative action to formally extend tribal women’s inheritance rights in India through amendments to existing laws or enactment of new legislation specifically addressing tribal women’s rights. Such legislative developments would provide additional statutory protection beyond the constitutional principles established in this judgment.

Future legal developments may also address the intersection between tribal autonomy and individual rights, potentially leading to more nuanced frameworks that respect cultural diversity while protecting fundamental rights. These developments could serve as models for other jurisdictions grappling with similar tensions between traditional practices and modern legal standards.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s judgment on tribal women’s inheritance rights represents a landmark victory for gender equality and constitutional justice in India. By establishing that tribal women and their legal heirs are entitled to equal shares in ancestral property, the court has taken a significant step toward eliminating gender-based discrimination in one of the most marginalized communities in Indian society.

The judgment’s significance extends beyond its immediate impact on inheritance rights to encompass broader principles of equality, justice, and human dignity. It demonstrates that constitutional principles must prevail over discriminatory customs, regardless of their historical or cultural significance. The court’s reasoning provides a framework for addressing other forms of discrimination while respecting cultural diversity and community autonomy.

The successful implementation of this judgment will require sustained efforts from government agencies, legal aid organizations, and civil society groups. These stakeholders must work together to ensure that the court’s ruling translates into practical benefits for tribal women across India. The judgment’s ultimate success will be measured not only by its legal impact but also by its contribution to broader social transformation within tribal communities.

As India continues its journey toward gender equality and social justice, the Supreme Court’s ruling on tribal women’s inheritance rights will be remembered as a pivotal moment when the highest court of the land affirmed that constitutional principles of equality and non-discrimination apply to all citizens, regardless of their community affiliation or cultural background. The judgment represents both an end and a beginning: an end to centuries of discrimination and a beginning of a more equitable future for tribal women and their families.

References

[1] ‘Excluding Female Heirs From Inheritance Discriminatory’: Supreme Court Allows Tribal Women Equal Succession Rights As Men. Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/supreme-court/excluding-female-heirs-from-inheritance-discriminatory-supreme-court-allows-tribal-women-equal-succession-rights-as-men-297937

[2] Constitution of India. (1950). Article 14 and Article 15.

[3] The Hindu Succession Act, 1956. Section 2(2).

[4] Madhu Kishwar v. State of Bihar, (1996) 5 SCC 125.

[5] United Nations. (1979). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-elimination-all-forms-discrimination-against-women

[6] The Print. (2025, January 24). SC grants inheritance rights to ST women via 1875 law, urges Centre to amend their succession laws. Available at: https://theprint.in/judiciary/sc-grants-inheritance-rights-to-st-women-via-1875-law-urges-centre-to-amend-their-succession-laws/2413607/