Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

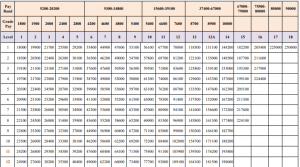

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

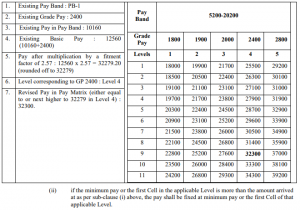

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

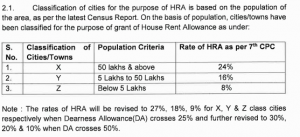

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

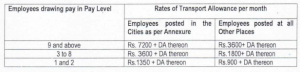

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Supreme Court on Land Acquisition Framework: Monetary Compensation Sufficient Unless Exceptional Circumstances Exist

Introduction

In a significant judgment that reshapes the understanding of landowner rights, the Supreme Court on land acquisition has clarified that rehabilitation for those displaced is not an absolute legal entitlement in every case. In its landmark ruling dated July 14, 2025, the apex court held that monetary compensation alone may suffice unless exceptional circumstances warrant additional rehabilitative measures.

This decision, delivered by a bench comprising Justices J.B. Pardiwala and Justice R. Mahadevan, represents a crucial clarification of the legal framework governing land acquisition in India. The judgment addresses the complex interplay between fair compensation and rehabilitation obligations, providing much-needed guidance to state governments, development authorities, and affected landowners across the country.

The ruling comes at a time when India continues to grapple with the challenges of balancing development needs with landowner rights, making this judicial pronouncement particularly significant for future acquisition proceedings.

The Supreme Court’s Landmark Ruling

Core Principles Established

The Supreme Court’s decision establishes several fundamental principles that will guide land acquisition proceedings moving forward. The court emphasized that when land is acquired for public purposes under the Land Acquisition Act or similar legislation, affected parties are entitled primarily to fair monetary compensation as per established legal principles.

Justice Pardiwala, speaking for the bench, articulated the court’s position clearly: “If land is required for any public purpose, law permits, the government or any instrumentality of government to acquire in accordance with the provisions of the Land Acquisition Act or any other State Act enacted for the purpose of acquisition. When land is acquired for any public purpose, the person whose land is taken away is entitled to appropriate compensation in accordance with the settled principles of law.”

The “Rarest of the Rare” Standard

The court introduced a significant threshold for additional rehabilitation measures, establishing that such provisions should only be considered in the “rarest of the rare” category of cases. This standard applies specifically to situations where the loss of land leads to complete insolvency or causes irreparable damage to the landowner’s livelihood.

This formulation draws inspiration from the established jurisprudence in criminal law while adapting it to the unique context of land acquisition proceedings. The court’s approach reflects a careful balance between protecting landowner interests and preventing the creation of unreasonable financial burdens on acquiring authorities.

Humanitarian Considerations and Fairness

While establishing monetary compensation as the primary remedy, the court recognized that exceptional circumstances might warrant additional measures. The bench emphasized that any such additional rehabilitation measures must be guided solely by humanitarian concerns of fairness and equity, rather than political considerations or populist motivations.

This distinction is crucial for understanding the court’s approach, as it acknowledges the human dimension of land acquisition while maintaining legal clarity and consistency in application.

Legal Framework Governing Land Acquisition in India

Evolution of Land Acquisition Laws

India’s land acquisition framework has undergone significant evolution since independence. The original Land Acquisition Act of 1894, enacted during British rule, remained the primary legislation for over a century before being replaced by the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013.

The 2013 Act represented a paradigm shift in approach, introducing comprehensive provisions for rehabilitation and resettlement alongside compensation. The Act regulates land acquisition and lays down procedures and rules for granting compensation, rehabilitation and resettlement to affected persons in India.

Constitutional Foundations

The constitutional framework surrounding land acquisition is anchored in Article 300A of the Constitution, which states that no person shall be deprived of property except by authority of law. This provision, while not conferring a fundamental right to property, establishes the legal foundation for acquisition proceedings.

The Supreme Court has consistently interpreted this provision to require adequate compensation for acquired land, though the scope and nature of such compensation has been subject to judicial interpretation over the decades.

Statutory Provisions Under the 2013 Act

The 2013 Act contains detailed provisions addressing both compensation and rehabilitation. Section 26 of the Act mandates that the Collector shall calculate compensation based on the higher of the registered sale deeds in the area, the average sale price under the Indian Stamp Act, or the minimum land value specified under the Indian Stamp Act.

The Act also provides for rehabilitation and resettlement packages under Chapter V, which includes provisions for infrastructure development, employment opportunities, and social security measures for affected families.

Case Analysis: Estate Officer, Haryana Urban Development Authority vs. Nirmala Devi

Background and Context

The dispute that gave rise to this important ruling centered on the interpretation of Haryana’s rehabilitation policies, specifically the schemes introduced in 1992 and 2016 (as amended in 2018). The case involved landowners who claimed entitlement to residential plot allotments under these rehabilitation schemes.

The landowners argued that they were prepared to pay the required fees under the 1992 scheme, positioning their claim as a legal right rather than a discretionary benefit. This framing of the issue brought into sharp focus the fundamental question of whether rehabilitation measures constitute legal entitlements or policy benefits.

State’s Defense and Temporal Challenges

The Haryana government opposed the landowners’ claims on multiple grounds, with the primary argument being that the civil suit was filed too late, some 14 to 20 years after the final acquisition award. This temporal dimension raised important questions about the statute of limitations and the continuing nature of rehabilitation obligations.

The state’s position reflected broader concerns about the practical challenges of implementing rehabilitation schemes, particularly when claims are made years or decades after the initial acquisition proceedings.

The Court’s Reasoned Decision

The Supreme Court’s analysis of the case demonstrates a careful consideration of both legal principles and practical realities. The court ruled that landowners could not claim allotment rights as a matter of law under the 1992 scheme, emphasizing the discretionary nature of such benefits.

However, the court also recognized the legitimate expectations of affected parties, allowing them to seek relief under the 2016 policy while establishing specific timelines for application and decision-making.

Judicial Precedents and Constitutional Principles

Historical Development of Compensation Jurisprudence

The Supreme Court’s approach to land acquisition compensation has evolved significantly over the decades. Early cases like Bella Banerjee v. State of West Bengal established the principle that compensation must be just and reasonable, while later decisions expanded this concept to include various factors affecting land value.

The landmark decision in Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, while primarily addressing constitutional amendment powers, also touched upon property rights and the scope of state authority in acquisition proceedings.

Contemporary Judicial Approach

Recent Supreme Court decisions have consistently emphasized the need for fair and adequate compensation while recognizing the state’s legitimate development objectives. The court has laid down constitutional tests for land acquisition, establishing procedural safeguards against arbitrary and illegal acquisition.

The current ruling builds upon this jurisprudential foundation while providing specific guidance on the relationship between compensation and rehabilitation obligations.

Balancing Development and Individual Rights

The Supreme Court’s approach reflects a sophisticated understanding of the competing interests at stake in land acquisition proceedings. The court recognizes that development projects serve important public purposes while acknowledging that individual property rights deserve protection and fair treatment.

This balancing act requires careful consideration of factual circumstances, legal principles, and policy objectives, making each case unique while maintaining consistency in judicial approach.

Implications for State Governments and Development Authorities

Policy Formulation and Implementation

The Supreme Court’s ruling has significant implications for how state governments approach rehabilitation policy formulation. The court’s criticism of “unwarranted rehabilitation schemes purely for appeasement” serves as a clear warning against politically motivated policy decisions that lack proper legal foundation.

State governments must now ensure that rehabilitation schemes are grounded in genuine humanitarian concerns and supported by adequate legal authority. This requirement may necessitate review of existing policies and more careful consideration of future initiatives.

Administrative Vigilance and Anti-Fraud Measures

The court’s specific direction regarding vigilance against “land grabbers and miscreants forming cartels” highlights the practical challenges of implementing rehabilitation schemes. Development authorities must establish robust verification mechanisms to ensure that benefits reach legitimate beneficiaries rather than opportunistic actors.

This administrative burden requires investment in capacity building, technology systems, and oversight mechanisms to prevent fraud and ensure policy effectiveness.

Transfer Restrictions and Long-term Planning

The court’s mandate that allotted plots carry transfer restrictions for at least five years represents a significant policy intervention. This restriction aims to prevent commercial speculation while ensuring that rehabilitation serves its intended purpose of providing genuine resettlement opportunities.

Development authorities must now establish mechanisms for monitoring compliance with these restrictions and processing applications for subsequent transfers through competent authorities.

Impact on Landowner Rights and Expectations

Clarification of Legal Entitlements

The Supreme Court’s ruling provides important clarity for landowners regarding their legal rights in acquisition proceedings. By establishing that rehabilitation is not an automatic entitlement, the court has clarified the scope of landowner expectations while maintaining protection for truly deserving cases.

This clarification helps landowners understand their position and make informed decisions about legal strategy and settlement negotiations.

Procedural Safeguards and Remedy Mechanisms

While limiting rehabilitation entitlements, the court has maintained important procedural safeguards for landowners. The requirement for fair compensation, coupled with humanitarian considerations for exceptional cases, ensures that landowner interests remain protected within the legal framework.

The court’s approach also preserves judicial oversight of acquisition proceedings, allowing for intervention in cases where genuine hardship or procedural irregularities occur.

Strategic Considerations for Legal Representation

The ruling has implications for legal strategy in land acquisition cases. Lawyers representing landowners must now focus on demonstrating exceptional circumstances that warrant additional rehabilitation measures, rather than claiming automatic entitlements.

This shift requires more nuanced legal arguments and comprehensive factual development to establish cases for special consideration.

Comparative Analysis with International Practices

Global Approaches to Land Acquisition

International experience with land acquisition reveals diverse approaches to balancing development needs with landowner rights. Some jurisdictions emphasize monetary compensation exclusively, while others incorporate comprehensive rehabilitation programs as standard practice.

The Supreme Court’s approach aligns with international trends toward proportionate responses that match remedial measures to the severity of impact, rather than adopting one-size-fits-all solutions.

Best Practices in Rehabilitation Policy

Successful rehabilitation programs in other jurisdictions typically feature clear eligibility criteria, transparent implementation mechanisms, and robust monitoring systems. The Supreme Court’s emphasis on preventing fraud and ensuring genuine resettlement reflects these international best practices.

The court’s approach also recognizes the importance of avoiding perverse incentives that might encourage false claims or speculative behavior.

Future Implications and Recommendations

Legislative Considerations

The Supreme Court’s ruling may prompt legislative review of existing land acquisition laws, particularly regarding the relationship between compensation and rehabilitation provisions. Future amendments might seek to codify the court’s principles while providing additional clarity for implementation.

Such legislative action could help reduce litigation by establishing clearer standards and procedures for determining when additional rehabilitation measures are appropriate.

Institutional Capacity Building

Effective implementation of the court’s directives requires significant institutional capacity building within development authorities and state governments. This includes training programs for officials, development of standard operating procedures, and establishment of monitoring systems.

Investment in these institutional capabilities is essential for ensuring that the court’s principles translate into effective policy implementation.

Technology and Transparency

Modern land acquisition processes increasingly rely on technology for mapping, valuation, and stakeholder engagement. The Supreme Court’s emphasis on preventing fraud and ensuring transparency aligns with trends toward digital governance and automated verification systems.

Development authorities should consider investing in technology solutions that enhance transparency, reduce administrative discretion, and improve accountability in rehabilitation program implementation.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Estate Officer, Haryana Urban Development Authority vs. Nirmala Devi represents a landmark clarification of India’s land acquisition framework. By establishing that monetary compensation is generally sufficient while preserving humanitarian exceptions for exceptional cases, the court has provided much-needed clarity for all stakeholders.

This judgment reflects the court’s sophisticated understanding of the competing interests at stake in land acquisition proceedings. The decision balances the legitimate development needs of the state with the property rights of individual landowners, while establishing clear standards for when additional measures may be warranted.

The ruling’s emphasis on preventing fraudulent claims and ensuring genuine resettlement demonstrates the court’s awareness of practical implementation challenges. By requiring transfer restrictions and administrative vigilance, the court has sought to protect the integrity of rehabilitation programs while maintaining their humanitarian purpose.

For state governments and development authorities, this decision provides clear guidance on policy formulation and implementation while emphasizing the importance of legal foundation and genuine humanitarian justification for rehabilitation measures. The court’s warning against politically motivated schemes serves as an important reminder of the need for principled governance in this sensitive area.

For landowners and their legal representatives, the ruling clarifies the scope of legal entitlements while maintaining protection for genuinely deserving cases. The decision encourages realistic expectations while preserving important procedural safeguards and judicial oversight.

As India continues its development trajectory, the balance between progress and individual rights remains a crucial challenge. The Supreme Court’s ruling provides a framework for navigating this balance in a manner that serves both public purposes and individual justice. The long-term impact of this decision will depend on how effectively it is implemented by lower courts, administrative authorities, and policy makers across the country.

The judgment ultimately reinforces the principle that land acquisition, while necessary for development, must be conducted with fairness, transparency, and genuine regard for the rights and welfare of affected individuals. This balance is essential for maintaining public confidence in development processes while ensuring that India’s growth trajectory remains inclusive and just.

References

[1] Supreme Court of India, Rehabilitation Not Necessary In Land Acquisition Cases Except For Those Who Lost Residence Or Livelihood, LiveLaw, Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/supreme-court/rehabilitation-not-necessary-in-land-acquisition-cases-except-for-those-who-lost-residence-or-livelihood-supreme-court-297857

[2] Estate Officer, Haryana Urban Development Authority vs. Nirmala Devi, Supreme Court of India, Civil Appeal No. 7707 of 2025, Available at: https://lawchakra.in/supreme-court/supreme-court-land-acquisition/

[3] Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Right_to_Fair_Compensation_and_Transparency_in_Land_Acquisition,_Rehabilitation_and_Resettlement_Act,_2013

[4] Supreme Court lays down 7 Constitutional Tests for Land Acquisition, CJP, Available at: https://cjp.org.in/supreme-court-lays-down-7-constitutional-tests-for-land-acquisition/

[5] Land Acquisition Law in India: Legal Framework, Challenges, and Reforms, Law Blend, Available at: https://lawblend.com/articles/land-acquisition-law-in-india/

[6] Supreme Court Ruling: Land Acquisition Rehabilitation Not Always Required, Down to Earth, Available at: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/environment/daily-court-digest-major-environment-orders-july-16-2025

Supreme Court Clarifies Application of Limitation Act to MSMED Act Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

Introduction

The Supreme Court of India has delivered a landmark judgment that significantly impacts the dispute resolution landscape for micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in the country. In a recent ruling, the apex court clarified the application of the Limitation Act, 1963, to proceedings under the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Act, 2006 (MSMED Act). This decision addresses longstanding confusion regarding the temporal boundaries within which MSME disputes must be initiated and resolved.

The judgment, delivered by a bench comprising Justices P.S. Narasimha and Joymalya Bagchi, has drawn a crucial distinction between arbitration and conciliation proceedings under the MSMED Act. This differentiation has far-reaching implications for how businesses approach dispute resolution, particularly in the context of delayed payments and contractual disputes involving MSMEs.

The Supreme Court’s Ruling: A Detailed Analysis

Core Findings of the Judgment

The Supreme Court’s decision establishes a clear framework for understanding the application of the Limitation Act to proceedings under the MSMED Act. The Court held that while the Limitation Act, 1963, applies to arbitration proceedings initiated under Section 18(3) of the MSMED Act, it does not extend to conciliation proceedings under Section 18(2) of the same Act.

Justice Narasimha, in his comprehensive 51-page judgment, emphasized that the distinction between these two forms of dispute resolution is fundamental to understanding the legislative intent behind the MSMED Act. The court’s reasoning reflects a nuanced understanding of the different purposes served by conciliation and arbitration in the context of MSME disputes.

Impact on Arbitration Proceedings

The ruling confirms that arbitration proceedings under the MSMED Act are subject to the same temporal limitations as other arbitration proceedings in India. This means that parties seeking to initiate arbitration for MSME-related disputes must do so within the prescribed limitation period, typically three years from the date when the cause of action arose [2].

This aspect of the judgment provides clarity for businesses and legal practitioners who had been uncertain about whether the special provisions of the MSMED Act created an exemption from general limitation principles. The court’s decision ensures consistency in the application of limitation law across different arbitration frameworks in India.

Conciliation Proceedings Remain Exempt

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the judgment is the court’s finding that conciliation proceedings under the MSMED Act remain exempt from the Limitation Act. The court reasoned that the expiry of the limitation period does not extinguish the underlying right to recover amounts due, and therefore, time-barred claims can still be referred to conciliation [3].

This distinction recognizes the fundamentally different nature of conciliation as a dispute resolution mechanism. Unlike arbitration, which results in a binding award, conciliation focuses on facilitating voluntary settlement between parties. The court’s approach acknowledges that the collaborative nature of conciliation makes it less appropriate to impose strict time limits.

Legal Framework: Understanding the MSMED Act’s Dispute Resolution Mechanism

Section 18 of the MSMED Act: The Foundation

Section 18 of the MSMED Act, 2006, establishes a comprehensive dispute resolution framework specifically designed for MSME-related disputes. This section provides a structured approach that begins with conciliation and may proceed to arbitration if conciliation fails.

The section reads: “Where any amount due to any micro or small enterprise under section 17 remains unpaid by the buyer, the supplier may make a reference to the Micro and Small Enterprises Facilitation Council.” This provision creates a statutory right for MSMEs to seek redress through specialized mechanisms rather than relying solely on traditional court proceedings.

The Three-Tier Dispute Resolution Process

The MSMED Act establishes a three-tier dispute resolution process that begins with reference to the Micro and Small Enterprises Facilitation Council (MSEFC). The process is designed to be efficient and cost-effective, recognizing the resource constraints typically faced by small businesses.

Under Section 18(2), the Council is required to conduct conciliation proceedings to resolve disputes. If conciliation fails, Section 18(3) provides for arbitration proceedings, either by the Council itself or through referral to an appropriate arbitration center. This structure ensures that parties have multiple opportunities to resolve their disputes without resorting to lengthy court proceedings.

Interaction with the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

The MSMED Act explicitly references the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, in Section 18(3), stating that “the provisions of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 shall then apply to the dispute as if the arbitration was in pursuance of an arbitration agreement.” This incorporation brings the entire framework of the Arbitration Act into play once arbitration proceedings commence [4].

This integration has been the subject of considerable judicial interpretation, with courts struggling to balance the special provisions of the MSMED Act with the general principles of arbitration law. The Supreme Court’s recent ruling provides much-needed clarity on this complex interaction.

Judicial Precedents and Their Evolution

Early Jurisprudence: The Silpi Industries Case

The foundation for understanding the application of Limitation Act to MSMED Act proceedings was laid in the Supreme Court’s decision in Silpi Industries v. Kerala State Road Transport Corporation [5]. This 2021 judgment established that the Limitation Act applies to arbitration proceedings under the MSMED Act, setting a precedent that has been consistently followed by subsequent courts.

The Silpi Industries case also addressed the maintainability of counter-claims in MSMED Act proceedings, holding that such claims are permissible within the statutory framework. This decision recognized the practical reality that commercial disputes often involve reciprocal claims and counter-claims.

The Bombay High Court’s Approach

The Bombay High Court has played a significant role in shaping the jurisprudence around MSMED Act proceedings. In several decisions, the court has emphasized that the MSMED Act’s provisions override general arbitration agreements between parties, reflecting the protective intent of the legislation.

The court’s approach has generally favored broad interpretation of the MSMED Act’s protective provisions, recognizing that the legislation was designed to address the specific challenges faced by small businesses in recovering dues from larger entities.

Recent Developments in High Courts

Various High Courts across India have contributed to the evolving understanding of MSMED Act proceedings. The Calcutta High Court recently ruled that even-numbered arbitration panels do not invalidate MSMED Act arbitrations, unlike under the general Arbitration Act [6]. This decision reflects the special nature of MSMED Act proceedings and their departure from standard arbitration principles.

Regulatory Framework and Institutional Mechanisms

The Micro and Small Enterprises Facilitation Council

The MSEFC serves as the primary institutional mechanism for MSMED Act dispute resolution. Established under Section 18 of the Act, the Council is designed to provide specialized expertise in handling MSME-related disputes. The Council’s composition typically includes representatives from relevant ministries, financial institutions, and industry associations.

The Council’s dual role as both a conciliation body and an arbitration facilitator reflects the Act’s emphasis on flexible dispute resolution. This institutional design allows for continuity in dispute handling while providing parties with multiple avenues for resolution.

State-Level Implementation

The implementation of MSMED Act provisions varies significantly across different states, reflecting local business environments and administrative capacities. Some states have established robust facilitation councils with regular sitting arrangements, while others have struggled with resource constraints and administrative challenges.

This variation in implementation has contributed to inconsistent application of the Act’s provisions, making the Supreme Court’s clarification all the more important for ensuring uniform standards across the country.

Practical Implications for Businesses and Legal Practitioners

Strategic Considerations for MSMEs

The Supreme Court’s ruling has significant strategic implications for MSMEs seeking to recover outstanding dues. The distinction between arbitration and conciliation proceedings means that businesses must carefully consider which mechanism to pursue based on their specific circumstances.

For time-barred claims, conciliation represents the primary avenue for recovery, as arbitration proceedings would be subject to limitation challenges. This reality may influence how MSMEs approach dispute resolution, potentially favoring early conciliation efforts over protracted negotiations.

Impact on Contractual Arrangements

The ruling also affects how parties structure their contractual relationships. While arbitration clauses remain valid and enforceable, the special provisions of the MSMED Act mean that MSMEs retain the right to invoke statutory dispute resolution mechanisms regardless of contractual terms.

This protection ensures that MSMEs cannot be forced to waive their statutory rights through contract negotiations, maintaining the protective intent of the MSMED Act even in sophisticated commercial arrangements.

Compliance Requirements for Buyers

Large enterprises and government entities that regularly engage with MSMEs must ensure compliance with both contractual obligations and statutory requirements. The Supreme Court’s ruling on the application of the Limitation Act to MSMED Act proceedings clarifies that limitation periods apply to formal arbitration, creating incentives for prompt dispute resolution

Buyers must also recognize that conciliation proceedings can be initiated even for time-barred claims, requiring ongoing attention to MSME relationships and potential disputes regardless of the passage of time.

Comparative Analysis with Other Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

Distinction from Commercial Court Proceedings

The MSMED Act’s dispute resolution mechanisms differ significantly from commercial court proceedings in terms of both procedure and limitation periods. While commercial courts are bound by general limitation principles, the MSMED Act’s conciliation provisions create a more flexible framework for older disputes.

This distinction reflects the recognition that MSMEs often face practical constraints in pursuing timely legal action, making rigid limitation periods particularly burdensome for smaller businesses.

Relationship with Insolvency Proceedings

The interaction between MSMED Act proceedings and insolvency law remains complex and evolving. Recent judicial decisions have emphasized that MSMED Act rights are not automatically extinguished by insolvency proceedings, but the practical enforcement of these rights in insolvency contexts requires careful consideration.

The Supreme Court’s ruling on limitation periods may influence how MSME claims are treated in insolvency proceedings, particularly regarding the timing of claim submissions and the validity of older claims.

Future Implications and Recommendations

Legislative Considerations

The Supreme Court’s decision highlights the need for continued legislative attention to MSME dispute resolution. While the current framework provides important protections, there may be scope for further refinement to address practical challenges in implementation.

Future amendments might consider standardizing procedures across states, establishing clear timelines for Council proceedings, and addressing the interaction between MSMED Act provisions and other commercial laws.

Institutional Strengthening

The effectiveness of MSMED Act dispute resolution depends heavily on the capacity and resources of facilitation councils. Strengthening these institutions through better funding, training, and administrative support could significantly improve outcomes for MSMEs.

Investment in technology and digital platforms could also enhance accessibility and efficiency, making it easier for small businesses to access dispute resolution services.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s clarification on the application of the Limitation Act to MSMED Act proceedings represents a significant development in Indian commercial law. By distinguishing between arbitration and conciliation proceedings, the court has provided a framework that balances the need for timely dispute resolution with the protective intent of MSME legislation.

This judgment will likely influence how businesses approach MSME disputes, encouraging early resolution efforts while preserving important rights for smaller enterprises. The decision also provides valuable guidance for legal practitioners and institutional stakeholders working within the MSMED Act framework.

As India continues to emphasize the importance of MSMEs in economic development, clear and consistent legal frameworks become increasingly crucial. The Supreme Court’s ruling contributes to this objective by providing certainty in an area that has been subject to considerable confusion and inconsistent interpretation.

The long-term impact of this decision will depend on how effectively it is implemented by lower courts, arbitration institutions, and facilitation councils across the country. With proper implementation, this clarification should enhance the effectiveness of MSME dispute resolution while maintaining the protective spirit of the MSMED Act.

References

[1] Supreme Court of India, Limitation Act Provisions Will Apply To Arbitration Proceedings Initiated Under Section 18(3) MSMED Act, LiveLaw, Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/limitation-act-provisions-arbitration-proceedings-msmed-act-supreme-court-176520

[2] Silpi Industries v. Kerala State Road Transport Corporation, Supreme Court of India, June 29, 2021, Available at: https://www.argus-p.com/updates/updates/supreme-court-decides-upon-the-aspects-of-limitation-counter-claim-and-registration-under-the-msmed-act/

[3] Navigating MSME Law in 2024: Key Judicial Pronouncements, SCC Times, Available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/01/29/navigating-msme-law-in-2024-key-judicial-pronouncements/

[4] Section 18 of MSMED Act, 2006: Reference to Micro and Small Enterprises Facilitation Council, IBC Laws, Available at: https://ibclaw.in/section-18-reference-to-micro-and-small-enterprises-facilitation-council/

[5] Court addresses limitation provisions under MSMED Act, Law.Asia, Available at: https://law.asia/court-addresses-limitation-provisions-msmed-act/

[6] Even if the number of Arbitrators are even, it does not attract any bar in an Arbitration under the MSMED Act, AM Legals, Available at: https://amlegals.com/even-if-the-number-of-arbitrators-are-even-it-does-not-attract-any-bar-in-an-arbitration-under-the-msmed-act/

Authorized and Published by Rutvik Desai

FIR Registration in India (2025): Supreme Court Guidelines and Section 173 of BNSS & CrPC Explained

Introduction

The Supreme Court’s recent ruling in Anurag Bhatnagar v. State (NCT of Delhi) (25 July 2025) has redrawn the roadmap for getting a First Information Report (FIR) registered. At the same time, India’s new procedural code — the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) — has overhauled the statutory mechanics of FIRs with fresh concepts like e-FIR, Zero-FIR and the legally recognised preliminary enquiry. This article unpacks the judgment, analyses the relevant provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) and the BNSS, and provides a step-by-step guide to FIR registration in 2025.

Overview

The Supreme Court has clarified that a magistrate should not ordinarily entertain a direct application under Section 156(3) CrPC unless the complainant has first exhausted the two-tier police remedy under Section 154(1) and (3). Simultaneously, BNSS Section 173 recasts FIR practice, introducing electronic filing and statutory recognition for Zero-FIRs and preliminary enquiries. This article explains the dual framework, offers practical filing tips, and contrasts CrPC versus BNSS procedures.

The Supreme Court’s July 2025 Decision

Key Facts

- Case: Anurag Bhatnagar & Anr. v. State (NCT of Delhi) & Anr.

- Bench: Justices Pankaj Mithal & S.V.N. Bhatti.

- Context: Complaint filed directly under Section 156(3) without first approaching Station House Officer (SHO) or Superintendent of Police (SP).

Core Holdings

| Holding | Exact Judicial Quote |

|---|---|

| Exhaust police remedies first | “An informant who wants to report about a commission of a cognizable offence has to, in the first instance, approach the officer-in-charge… It is only subsequent to availing the above opportunities… he may approach the Magistrate under Section 156(3).” |

| Magistrate’s jurisdiction not barred but use is “irregular” if remedies skipped | “Entertaining an application directly by the Magistrate is a mere procedural irregularity… the action of the Magistrate may not be illegal or without jurisdiction.” |

| Step-wise hierarchy reaffirmed | “The Magistrate ought not to ordinarily entertain an application under Section 156(3) CrPC directly unless the informant has availed and exhausted his remedies provided under Section 154(3).” |

The Classical CrPC Framework

Sequential Remedies Under CrPC

| Stage | Provision | What the Complainant Must Do | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Section 154(1) | Go to officer-in-charge (SHO) of jurisdictional police station, give information orally/writing. | SHO must register FIR or record refusal. |

| 2 | Section 154(3) | If SHO refuses, send the complaint in writing (by post/email) to the SP/DCP. | SP may investigate or direct investigation. |

| 3 | Section 156(3) | If SP also fails, file an application before the Magistrate (supported by affidavit as per Priyanka Srivastava 2015). | Magistrate may order registration/investigation. |

| 4 | Section 190 | Alternatively, file a private complaint for direct cognisance. | Magistrate follows Sections 200-204. |

Failure to follow Steps 1-2 makes a direct S. 156(3) plea “irregular”, not void, but courts may dismiss it[1].

BNSS 2023: A New FIR Architecture

Section 173 – Five Game-Changing Elements

| BNSS Feature | Clause | Practical Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Universal jurisdiction & Zero-FIR | 173(1) | Any police station must register, even if the crime occurred elsewhere. |

| e-FIR | 173(1)(ii) | Information can be sent electronically; complainant must sign within 3 days. |

| Women & vulnerable-friendly recording | First & second provisos | Mandatory woman officer, video-recording, interpreter/special educator where applicable. |

| Preliminary Enquiry window | 173(3) | For offences punishable ≥3 years <7 years, SHO may with DSP-rank approval conduct a 14-day enquiry before FIR. |

| SP-level escalation retained | 173(4) | Mirrors Section 154(3), preserving escalation to SP before magistrate approach. |

CrPC vs BNSS: A Side-by-Side Snapshot

| Theme | CrPC (Section 154) | BNSS (Section 173) |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic filing | Not recognised | Explicit e-FIR with 3-day signature rule |

| Zero-FIR | Only via SC/HC jurisprudence | Statutory mandate |

| Preliminary Enquiry | Generally impermissible post Lalita Kumari | Statutory 14-day window for 3-7 year offences |

| Victim-centric safeguards | Limited to sexual-offence proviso | Expanded to disability, video-graphy |

“Sub-Section (3) … is a significant departure from Section 154 of the CrPC.”[2]

Step-by-Step Guide to FIR Registration in 2025

1. Collect Basic Data

Prepare offence date, place, accused details (if known), witness list, documentary/proof material, and your ID proof.

2. Choose Filing Mode (BNSS-Era Options)

- Physical FIR: Walk into any police station (Zero-FIR concept removes jurisdiction barrier).

- e-FIR: Upload complaint via State/UT online portal or email to SHO; sign within 3 days.

- Helpline / Telephone: Record becomes FIR only after written/e-signed confirmation.

3. Demand the FIR Number

Under BNSS s.173(2) the informant must receive a free copy instantly.

4. If SHO Refuses

- Send a written complaint to the SP/DCP by post or email (BNSS s.173(4)).

- Track acknowledgment; keep postal receipt/email log.

5. If SP/DCP Fails

- File a sworn application under Section 156(3) CrPC (still applicable despite BNSS) before the jurisdictional Magistrate.

- Attach (i) copy of complaint to SHO, (ii) copy of letter/email to SP, (iii) affidavit of truth, (iv) supporting documents.

6. Alternative: Private Complaint

Proceed under Section 190 CrPC; Magistrate takes cognisance after recording of statement under Section 200.

Practical Drafting Tips for the Section 156(3) Application

-

Chronology: Clearly date each police approach.[3]

-

Affidavit: Follow Priyanka Srivastava requirement to deter frivolous filings .[3]

-

Relief Clause: Explicitly pray for registration of FIR and monitored investigation.

-

Annexures: Serial-number and paginate every document.

-

Court Fee: Check State amendments (some require nominal fees).

Tables for Quick Reference

Table 1: Remedies Ladder – From SHO to High Court

| Level | Provision | Decision-Maker | Typical Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHO | 154(1) CrPC / 173(1) BNSS | Sub-Inspector/Inspector | Immediate |

| SP | 154(3) CrPC / 173(4) BNSS | Superintendent of Police | Few days |

| Magistrate (Investigation) | 156(3) CrPC | Judicial Magistrate | Varies; 1–3 weeks |

| Magistrate (Cognisance) | 190 CrPC | Judicial Magistrate | Same day/short |

| High Court | 482 CrPC | High Court | Discretionary, exceptional |

Table 2: Major FIR-Related Innovations in BNSS

| Innovation | Section | Purpose | Impact |

| e-FIR | 173(1)(ii) | Paperless lodging | Faster, transparent |

| Zero-FIR | 173(1) | Any PS can register | Ends jurisdiction excuse |

| Preliminary Enquiry | 173(3) | Filter borderline cases | Balances rights |

| Mandatory SP escalation | 173(4) | Oversight | Reduces SHO arbitrariness |

| Victim-centric recording | 173 provisos | Inclusivity & dignity | Safer reporting for women, disabled |

Draft Sample Complaint Templates

A. Police Station Complaint Format (Physical or Email)

To

The Station House Officer

[Police Station Name & Address]

Subject: Information regarding cognizable offence under Sections 420/406 BNS

Sir/Madam,

I, [Name, age, address], state as follows:

1. On 12 July 2025 at 10:30 AM…

2. The accused, [details]…

3. Offence description…

Kindly register an FIR under Section 173 BNSS and investigate.

Attached: Evidence list (Annexures A-D).

Thank you,

[Signature / digital signature]

[Contact]

B. Section 156(3) Application Skeleton

IN THE COURT OF THE Ld. [Chief Metropolitan Magistrate]

[District & State]

Application under Section 156(3) CrPC read with Section 173 BNSS

Applicant: [Name & address]

Versus

Respondent: State (through SHO, …)

Most respectfully submitted:

1. FIR refusal dated… enclosed as Annexure P-1.

2. SP representation dated… Annexure P-2.

3. Facts constitute offences under Sections 420, 406 BNS.

4. Prayer: a) Order SHO to register FIR;

b) Monitor investigation;

c) Pass further orders.

Filed by

[Advocate details]

Enforcement Timelines & Future Litigation Trends

-

July 2024 – BNSS came into force; Section 173 immediately applicable.

-

July 2025 & beyond – SC’s Anurag Bhatnagar ruling serves as binding precedent for magistrates nationwide.

-

Tech integration – State DGPs mandated to roll out e-FIR portals; expect writs on delayed portal deployment.

-

Preliminary Enquiry Challenges – Defence counsel likely to attack FIRs citing non-compliance with 14-day PE window. Courts will evolve PE jurisprudence.

Compliance Checklist for Police Officers

| Task | CrPC / BNSS Clause | Deadline | Cross-Check |

| Enter oral information in FIR register | 173(1)(i) | Immediate | GD entry number |

| Acknowledge e-FIR & collect signature | 173(1)(ii) | Within 3 days | Digital audit log |

| Provide free FIR copy | 173(2) | Immediate | Signature of receipt |

| Decide PE vs direct investigation | 173(3) | 14 days | DSP approval memo |

| Update victim on progress | 193 BNSS | 90 days | Email/SMS record |

Conclusion

The twin forces of Supreme Court jurisprudence and the BNSS statutory overhaul have together created a clearer, more technology-friendly and citizen-centric pathway for FIR registration in India. Complainants must, however, respect the hierarchy: approach the police twice (SHO, then SP) before invoking judicial machinery under Section 156(3). Conversely, police officers are now bound by stricter timelines, digital transparency mandates, and enhanced victim-sensitive protocols.

By understanding these layered procedures and citing the July 2025 Supreme Court ruling alongside Section 173 BNSS, litigants, journalists and legal professionals can navigate FIR registration with clarity and confidence.

Key Takeaways

-

Police First: Always attempt SHO and SP before filing under Section 156(3).

-

BNSS Section 173: Embraces e-FIR, Zero-FIR, preliminary enquiry.

-

Magistrate Power: Still intact, but ordinarily secondary.

-

Digital Evidence: Ensure email receipts, online acknowledgments; they are admissible.

-

Victim-Friendly: Women, children and disabled complainants enjoy enhanced safeguards.

Following these guidelines will ensure your FIR journey is legally sound, efficient and fully compliant with India’s updated criminal justice framework.

Frequently Asked Questions

| Question | Answer |

| Can I file an FIR from abroad? | Yes. Send e-complaint; BNSS requires SHO to record and later obtain your signature by electronic authentication or embassy facilitation. [4] |

| What if the offence is punishable with 5 years? | SHO may open a 14-day preliminary enquiry with DSP permission under 173(3). If prima facie case exists, FIR follows. |

| Is Zero-FIR transferable? | Yes. After registration, the Zero-FIR is digitally transferred to the station of actual jurisdiction for investigation. |

| Do I need a lawyer to file an FIR? | Not mandatory. Legal counsel helps in complex or sensitive matters. |

| Are false FIRs punishable? | Yes. Sections 194–195 Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) penalise false information. |

References

1. ANURAG BHATNAGAR & ANR. …PETITIONER(S) VERSUS STATE (NCT OF DELHI) & ANR. Available at : https://api.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2024/43744/43744_2024_12_1501_62665_Judgement_25-Jul-2025.pdf

2. The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 Available at : https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/20099

3. Om Prakash Sharma Vs. State of M.P. and another Available at: https://mpsja.mphc.gov.in/Joti/pdf/LU/Guidelines%20for%20Magistrates%20156.pdf

4. BNSS Section 173 – Information in cognizable cases Available at : https://www.latestlaws.com/bare-acts/central-acts-rules/bnss-section-173-information-in-cognizable-cases/

Supreme Court Upholds UGC Regulations Supremacy: Landmark Judgment Quashes Punjab Assistant Professor Appointments for Constitutional Violations

Introduction

The Supreme Court of India delivered a landmark judgment on July 14, 2025, in the case of Mandeep Singh & Ors. v. State of Punjab & Ors. [1], fundamentally reaffirming the supremacy of University Grants Commission (UGC) regulations over state-specific recruitment procedures in higher education. The judgment, delivered by a bench comprising Justice Sudhanshu Dhulia and Justice K. Vinod Chandran, quashed the appointments of 1,091 Assistant Professors and 67 Librarians made by the Punjab Government in October 2021, marking a significant victory for academic integrity and constitutional governance. In a moment that will shape recruitment practices across the country, the Supreme Court upholds UGC regulations as binding on states that have adopted them, effectively resolving tensions between national standards and regional autonomy in academic hiring.

This decision represents a crucial intervention in the ongoing tension between federal educational standards and state autonomy in recruitment processes. The court’s ruling not only addresses the immediate concerns regarding the Punjab appointments but also establishes important precedents for the future conduct of academic recruitment across all states in India. The judgment emphasizes that once a state adopts UGC regulations, it becomes constitutionally bound to follow them, regardless of any conflicting state-specific procedures.

Constitutional and Legal Framework

Federal Structure and Educational Governance

The Indian Constitution’s Seventh Schedule delineates the distribution of powers between the Union and State governments through three lists: Union List, State List, and Concurrent List. Education finds its place in the Concurrent List as Entry 25, which grants both Union and State governments the power to legislate on educational matters. However, Entry 66 of the Union List specifically empowers the Union government to coordinate and determine standards in institutions of higher education, including research and technical institutions.

This constitutional framework creates a hierarchy where Union legislation on educational standards takes precedence over state laws when there is a conflict. The Supreme Court has consistently held that coordination of educational standards at the national level is essential for maintaining uniformity and quality in higher education across the country.

UGC’s Statutory Authority

The University Grants Commission was established under the University Grants Commission Act, 1956 [2], as a statutory body responsible for the coordination, determination, and maintenance of standards of university education in India. The UGC’s authority extends to all universities and colleges affiliated with universities, making it the apex body for higher education regulation.

The UGC Regulations on Minimum Qualifications for Appointment of Teachers and Other Academic Staff in Universities and Colleges and Measures for the Maintenance of Standards in Higher Education, 2018 [3], form the cornerstone of academic recruitment in India. These regulations establish comprehensive guidelines for the appointment of faculty members, including detailed criteria for academic qualifications, research experience, and selection procedures.

Article 14 and Equal Protection

Article 14 of the Constitution guarantees equality before the law and equal protection of laws to all persons within the territory of India. This fundamental right encompasses the principle of reasonableness in state action, requiring that government decisions be based on relevant considerations and follow established procedures. The Supreme Court has consistently held that arbitrary state action, particularly in matters of public employment, violates Article 14.

The doctrine of equality under Article 14 requires that similarly situated individuals be treated equally, and any classification must be reasonable and have a nexus with the object sought to be achieved. In the context of public employment, this means that recruitment procedures must be fair, transparent, and based on merit.

Case Background and Factual Matrix

The Punjab Recruitment Process

The controversy surrounding the Punjab appointments began when the state government decided to recruit 1,158 faculty members for its government degree colleges through an expedited process that deliberately bypassed established UGC norms. The recruitment was conducted through a Departmental Selection Committee rather than the Punjab Public Service Commission (PPSC), which is the constitutional body mandated to conduct such recruitments under the Punjab Educational Services Class II Rules, 1976.

The state government replaced the comprehensive UGC selection procedure, which includes evaluation of Academic Performance Index (API), teaching experience, research contributions, and structured interviews, with a single written test consisting of multiple-choice questions. This dramatic deviation from established norms was justified by the state on grounds of urgency and the need to fill vacant positions in newly established colleges.

Timeline and Political Context

The recruitment process was initiated with unprecedented speed, with the entire exercise completed within two months, including a 45-day application period. The timing of this recruitment, coming just before the 2022 State Assembly elections, raised serious questions about the political motivations behind the decision. The petitioners argued that the hasty nature of the recruitment was designed to benefit certain candidates and constituencies in the run-up to the elections.

The state government’s decision to abandon the established UGC procedure was made without any prior consultation with stakeholders, academic bodies, or the PPSC. This unilateral decision-making process violated principles of administrative fairness and transparency that are fundamental to constitutional governance.

Impact on Academic Community

The Punjab government’s decision affected not only the candidates who were appointed through the irregular process but also those who had been preparing for recruitment under the established UGC norms. The deviation from standard procedures created uncertainty in the academic community and undermined confidence in the merit-based selection process.

The irregular appointments also had broader implications for the quality of education in Punjab’s government colleges, as the abbreviated selection process failed to adequately assess the teaching capabilities and research potential of candidates. This raised concerns about the long-term impact on educational standards in the state.

Supreme Court’s Analysis and Reasoning

Supremacy of UGC Regulations

The Supreme Court’s analysis began with a thorough examination of the constitutional framework governing education and the specific powers of the UGC. The court reaffirmed the principle established in the Adhyaman Educational Institute case [4] that UGC regulations have primacy over conflicting state regulations due to the Union’s power under Entry 66 of List I, which overrides Entry 25 of List III in the Seventh Schedule.

In this context, the Supreme Court upholds UGC regulations as constitutionally binding, underscoring that the UGC’s role in coordinating and determining standards in higher education institutions is not merely advisory but carries the force of law. Once a state adopts UGC regulations, it becomes constitutionally obligated to follow them in letter and spirit. The court noted that the Punjab government had officially adopted the UGC Regulations 2018, making compliance mandatory rather than optional.

Analysis of Selection Procedures

The Supreme Court conducted a detailed analysis of the UGC’s prescribed selection procedures for Assistant Professors and Librarians. The UGC Regulations 2018 establish a comprehensive framework that includes multiple components: academic record evaluation (50% weightage), domain knowledge and teaching skills assessment (30% weightage), and interview performance (20% weightage). This multi-faceted approach ensures that candidates are evaluated holistically rather than on the basis of a single parameter.

The court noted that the Academic Performance Index (API) system, which forms a crucial component of the UGC selection process, is designed to evaluate candidates’ research contributions, teaching experience, and academic achievements in a standardized manner. This system ensures that appointments are based on merit and academic excellence rather than subjective considerations.

Violation of Natural Justice

The Supreme Court found that the Punjab government’s decision to abandon the established selection procedure without providing adequate justification violated principles of natural justice. The court emphasized that the sudden change in procedure, implemented without prior notice or consultation, denied candidates the opportunity to prepare adequately for the selection process under the new system.

The court also noted that the elimination of the interview component, which allows for direct assessment of candidates’ teaching abilities and subject knowledge, fundamentally altered the nature of the selection process. This change was made without any reasoned justification and appeared to be motivated by considerations of convenience rather than merit.

Article 14 Violations

The Supreme Court held that the Punjab government’s recruitment process violated Article 14 of the Constitution in multiple ways. First, the arbitrary nature of the decision to change the selection procedure without adequate justification constituted unreasonable state action. Second, the hasty implementation of the new procedure denied equal treatment to candidates who had been preparing under the established system.

The court referenced several precedents, including Ramana Dayaram Shetty v. International Airport Authority of India [5], to establish that state action must be reasonable, non-arbitrary, and based on relevant considerations. The Punjab government’s decision failed to meet these constitutional standards.

Consultation with Public Service Commission

The Supreme Court also addressed the violation of Article 320(3) of the Constitution, which mandates consultation with the Public Service Commission in matters of recruitment to public services. The court noted that the Punjab government’s decision to bypass the PPSC and conduct recruitment through a Departmental Selection Committee violated this constitutional requirement.

Article 320(3) requires that the Public Service Commission be consulted on all matters relating to methods of recruitment to civil services and civil posts. This consultation is not merely procedural but serves the important function of ensuring that recruitment processes are conducted fairly and transparently.

Judicial Precedents and Legal Principles

Adhyaman Educational Institute Precedent

The Supreme Court, while reaffirming its position, extensively relied on the Adhyaman Educational Institute (P) Ltd. v. Union of India [4] case, which established the fundamental principle that UGC regulations are binding on all educational institutions, including state-run institutions. This precedent clarified that the Supreme Court upholds the primacy of UGC regulations and that state laws, including delegated legislation, cannot be inconsistent with the standards specified by the UGC.

The Adhyaman judgment recognized the UGC’s role as the national coordinating body for higher education and established that uniformity in educational standards is essential for maintaining quality across the country. The court noted that allowing states to deviate from UGC norms would undermine the fundamental purpose of having a national coordinating body.

Reasonableness and State Action

The court referenced the landmark judgment in Sivanandan C.T. v. High Court of Kerala [6], which established that state orders must follow principles of consistency, foreseeability, and transparency. The Punjab recruitment process failed to meet these standards, as it was implemented hastily without adequate consultation or justification.

The court also cited Zenit Mataplast v. State of Maharashtra [7] to establish that arbitrary and precipitate state action violates Article 14. The Punjab government’s decision to change the recruitment procedure at short notice without adequate justification constituted such arbitrary action.

Legitimate Expectations Doctrine

The Supreme Court applied the doctrine of legitimate expectations, which holds that when a government creates expectations through its policies and procedures, it cannot arbitrarily change those expectations without adequate justification. The Punjab government had adopted the UGC Regulations 2018, creating legitimate expectations among potential candidates that recruitment would be conducted according to those standards.

The court noted that candidates who had been preparing for recruitment under the UGC norms had legitimate expectations that the established procedure would be followed. The arbitrary change in procedure violated these expectations and constituted unfair treatment.

Regulatory Framework and Implementation Challenges

UGC Regulations 2018: Comprehensive Framework

The UGC Regulations on Minimum Qualifications for Appointment of Teachers and Other Academic Staff in Universities and Colleges, 2018 [3], represent a comprehensive framework designed to ensure quality and uniformity in academic appointments across India. These regulations establish detailed criteria for different academic positions, including minimum educational qualifications, research experience requirements, and standardized selection procedures.

The regulations require that candidates for Assistant Professor positions possess a Master’s degree with at least 55% marks and qualify in the National Eligibility Test (NET) or State Eligibility Test (SET). Additionally, the regulations establish the Academic Performance Index (API) system, which quantifies candidates’ research contributions, teaching experience, and academic achievements.

Implementation Challenges in State Systems

The implementation of UGC regulations in state educational systems faces several challenges, including resource constraints, administrative capacity limitations, and resistance to change. Many states have established their own procedures and systems over the years, creating institutional inertia that makes it difficult to adopt new standards and procedures.

The Punjab case highlights the need for better coordination between the UGC and state governments to ensure smooth implementation of national standards. This includes providing adequate support for capacity building, training of personnel, and development of necessary infrastructure.

Role of Public Service Commissions

Public Service Commissions play a crucial role in ensuring fair and transparent recruitment processes in state government services. Article 320 of the Constitution establishes the constitutional mandate for Public Service Commissions and requires their consultation in matters of recruitment. The Punjab case demonstrates the importance of maintaining this constitutional requirement and the consequences of bypassing these institutions.

The expertise and experience of Public Service Commissions in conducting fair and transparent recruitment processes make them essential partners in implementing UGC regulations at the state level. Their involvement ensures that recruitment processes meet constitutional standards and maintain public confidence in the merit-based selection system.

Impact on Higher Education Governance

Strengthening Federal Standards

The Supreme Court’s judgment in the Punjab case significantly strengthens the federal framework for higher education governance in India. By reaffirming that the Supreme Court upholds UGC regulations over state-specific procedures, the court has ensured that national standards for academic appointments will be maintained across all states.

This decision is particularly important in the context of India’s federal structure, where the tendency toward state autonomy can sometimes conflict with the need for national coordination in critical areas like education. The judgment establishes clear boundaries and ensures that the UGC’s coordinating role is not undermined by state-specific deviations.

Implications for Academic Quality

The enforcement of UGC regulations has significant implications for academic quality in Indian higher education. The comprehensive selection procedures prescribed by the UGC ensure that appointments are based on merit and academic excellence rather than political considerations or administrative convenience.

The judgment also sends a strong message to state governments that attempts to compromise academic standards for political or administrative reasons will not be tolerated by the courts. This is likely to encourage greater compliance with UGC norms and improve the overall quality of academic appointments.

Protection of Merit-Based Selection

The Supreme Court’s decision provides strong protection for merit-based selection in academic appointments. By striking down the Punjab government’s attempt to replace comprehensive evaluation procedures with a simple written test, the court has reinforced the principle that academic appointments must be based on thorough assessment of candidates’ qualifications and capabilities.

This protection is particularly important in the current context, where there are increasing pressures on academic institutions to compromise on merit for various reasons. The judgment establishes clear judicial backing for maintaining high standards in academic recruitment.

Constitutional Principles and Administrative Law

Separation of Powers and Judicial Review

The Punjab case demonstrates the important role of judicial review in maintaining constitutional governance and preventing administrative overreach. The Supreme Court’s intervention prevented the Punjab government from implementing a recruitment process that violated constitutional principles and statutory requirements.

The judgment also illustrates the delicate balance between respecting state autonomy and ensuring compliance with constitutional requirements. While states have significant autonomy in governance matters, this autonomy cannot be exercised in a manner that violates constitutional principles or statutory obligations.

Procedural Due Process

The court’s emphasis on procedural due process in the Punjab case highlights the importance of following established procedures in administrative decision-making. The requirement that government decisions be based on adequate consultation, proper justification, and compliance with statutory requirements is fundamental to constitutional governance.

The violation of procedural due process in the Punjab case not only affected the specific recruitment process but also undermined public confidence in the fairness and transparency of government decision-making. The court’s intervention helped restore confidence in the system and established important precedents for future cases.

Transparency and Accountability

The Supreme Court’s judgment emphasizes the importance of transparency and accountability in government decision-making. The Punjab government’s decision to change the recruitment procedure without adequate consultation or justification violated these fundamental principles of democratic governance.

The court’s requirement that government decisions be based on reasoned justification and proper consultation serves as an important check on arbitrary exercise of power. This requirement is particularly important in matters of public employment, where fairness and transparency are essential for maintaining public confidence.

Future Implications and Recommendations

Strengthening Coordination Mechanisms

The Punjab case highlights the need for stronger coordination mechanisms between the UGC and state governments to ensure smooth implementation of national standards. This includes regular consultation, capacity building programs, and technical support for states in implementing UGC regulations.

The development of standardized procedures and guidelines for states to follow when implementing UGC regulations would help prevent future conflicts and ensure consistent application of national standards across all states.

Enhancing Compliance Monitoring

The case also demonstrates the need for enhanced monitoring of compliance with UGC regulations. The UGC should establish robust monitoring mechanisms to ensure that states are following prescribed procedures and standards in academic appointments.

Regular audits and reviews of state recruitment processes would help identify potential violations early and allow for corrective action before problems escalate to litigation. This would benefit both the states and the academic community by ensuring consistent application of standards.

Capacity Building for State Institutions