Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

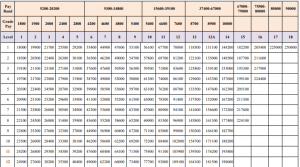

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

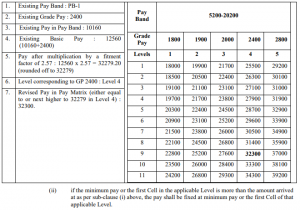

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

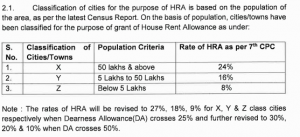

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

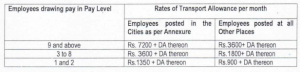

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Mental and Workplace Harassment Laws in India: Legal Framework and Key IPC Provisions

Introduction

Mental and workplace harassment continues to be a pressing concern in contemporary Indian society, affecting thousands of individuals across various professional and personal contexts. While India lacks a singular statute exclusively dedicated to mental harassment, the Indian Penal Code of 1860 provides several provisions that address different dimensions of harassment, intimidation, and cruelty. These provisions serve as critical legal instruments for victims seeking redress against psychological abuse, workplace bullying, and various forms of mental torture that often leave invisible yet deeply damaging scars on individuals.

The challenge with mental and workplace harassment lies in its intangible nature. Unlike physical injuries that present visible evidence, psychological distress manifests through behavioral changes, emotional trauma, and mental health deterioration that may not be immediately apparent or easily provable in legal proceedings. Nevertheless, the Indian legal system has evolved to recognize that mental cruelty can be equally, if not more, damaging than physical violence. Through various sections of the Indian Penal Code, lawmakers have attempted to provide protective mechanisms for individuals facing different forms of harassment, particularly focusing on vulnerable groups including women in marital relationships and workplace environments.

This examination delves into five crucial sections of the Indian Penal Code that specifically address mental and workplace harassment: Section 503 dealing with criminal intimidation, Section 294 concerning obscene acts, Section 509 protecting women’s modesty, Section 354A addressing sexual harassment, and Section 498A dealing with cruelty against married women. Understanding these provisions, their scope, limitations, and judicial interpretations becomes essential for anyone seeking protection against harassment or defending against potential misuse of these laws.

Understanding Criminal Intimidation Under Section 503 IPC

Criminal intimidation represents one of the most common forms of mental harassment in both workplace and personal contexts. Section 503 of the Indian Penal Code defines criminal intimidation as threatening any person with injury to their person, reputation, or property, or to the person or reputation of anyone in whom that person is interested, with intent to cause alarm, or to compel that person to do any act they are not legally bound to do, or to omit any act which that person is legally entitled to do. This provision recognizes that threats and intimidation, even without physical violence, constitute serious offenses that undermine an individual’s sense of security and autonomy.

The application of this section extends broadly to workplace environments where employees may face threats from superiors, colleagues, or subordinates. Such intimidation might involve threats of termination without cause, threats to damage professional reputation, or coercion to perform tasks beyond job responsibilities. The mental distress caused by continuous intimidation can lead to anxiety, depression, and other psychological conditions that significantly impact an individual’s quality of life and professional performance. Courts have recognized that the essence of this offense lies in the threat itself and the mental impact it creates, rather than requiring actual execution of the threatened action.

The punishment prescribed under Section 503 includes imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to two years, or with fine, or with both. While this may appear lenient compared to offenses involving physical harm, the provision acknowledges the serious nature of psychological pressure and its potential to cause significant distress. The legal framework requires prosecutors to establish that the accused deliberately made threats with the intention of causing alarm or compelling specific actions, thereby protecting individuals from frivolous allegations while ensuring genuine victims receive appropriate legal recourse.

In workplace contexts specifically, Section 503 becomes particularly relevant when employees face systematic intimidation designed to force resignations, accept unfavorable terms, or remain silent about organizational malpractices. The provision empowers victims to seek criminal action against perpetrators without necessarily having to prove physical harm or visible injury. However, successful prosecution requires demonstrating that the threats were credible, intentional, and caused genuine apprehension in the victim’s mind, making proper documentation and evidence collection crucial for pursuing cases under this section.

Addressing Public Obscenity Through Section 294 IPC

Section 294 of the Indian Penal Code addresses situations where obscene acts or songs are performed in public places, causing annoyance to others. This provision states that whoever, to the annoyance of others, does any obscene act in any public place, or sings, recites or utters any obscene song, ballad or words, in or near any public place, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three months, or with fine, or with both. While seemingly focused on public decency, this section has significant implications for workplace harassment cases where verbal abuse, inappropriate comments, or obscene behavior creates hostile environments for employees.

The interpretation of what constitutes obscenity under this section has evolved through judicial pronouncements, with courts recognizing that obscenity must be viewed in context rather than through absolute standards. In workplace settings, this provision becomes applicable when employees are subjected to vulgar language, sexual innuendos, or inappropriate jokes that create discomfort and undermine professional dignity. The key requirement is that such acts occur in public spaces or within hearing or viewing distance of others, thereby distinguishing it from private communications or isolated incidents.

The relationship between Section 294 and workplace harassment becomes particularly evident in cases involving verbal abuse during meetings, inappropriate comments made in common areas, or circulation of obscene materials in office environments. The provision recognizes that exposure to obscene behavior, even without direct physical contact or explicit threats, constitutes a form of harassment that affects mental well-being and creates toxic work atmospheres. Victims can invoke this section to address situations where they are subjected to crude language or behavior that violates professional decorum and personal dignity.

However, the application of Section 294 requires careful consideration of several factors including the public nature of the act, the intention behind the behavior, and whether it genuinely caused annoyance to others. Courts have held that mere use of colorful language or casual profanity may not automatically constitute obscenity unless it crosses certain thresholds of decency and causes genuine distress. This nuanced approach ensures that the provision is not used to stifle free expression while simultaneously protecting individuals from genuinely offensive and harassing behavior in professional and public spaces.

Protecting Women’s Modesty Under Section 509 IPC

Section 509 of the Indian Penal Code specifically addresses acts intended to insult the modesty of women through words, gestures, sounds, or the display of objects. The provision states that whoever, intending to insult the modesty of any woman, utters any word, makes any sound or gesture, or exhibits any object, intending that such word or sound shall be heard, or that such gesture or object shall be seen, by such woman, or intrudes upon the privacy of such woman, shall be punished with simple imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years, and shall also be liable to fine. This section recognizes that harassment need not involve physical contact and that verbal and non-verbal actions can constitute serious offenses against women’s dignity.

The scope of Section 509 extends to various forms of workplace harassment including catcalling, whistling, making suggestive gestures, staring inappropriately, or making comments about a woman’s appearance or body that are intended to embarrass or demean her. The provision specifically criminalizes intrusion upon privacy, which has gained increased relevance in the digital age where workplace harassment may extend to unwanted messages, sharing of inappropriate images, or surveillance without consent. The emphasis on intention distinguishes this provision from accidental or innocent actions that might inadvertently cause discomfort.

In workplace contexts, Section 509 provides crucial protection against what is commonly termed as gender-based harassment. Women employees facing persistent unwanted attention, comments about their physical appearance, or gestures of a sexual nature can invoke this provision regardless of whether such behavior escalates to physical assault. The provision acknowledges that such conduct creates hostile work environments, undermines professional relationships, and causes significant psychological distress that can affect career progression and mental health. The relatively lower threshold of proof compared to more serious sexual offenses makes this provision accessible for addressing everyday mental and workplace harassment that might otherwise go unreported. Judicial interpretation has expanded the understanding of modesty beyond Victorian notions to encompass contemporary concepts of dignity, respect, and personal autonomy. Courts have recognized that what insults a woman’s modesty should be determined not by outdated social mores but by whether the action violated her sense of personal dignity and caused mental anguish. This progressive interpretation ensures that Section 509 remains relevant in addressing modern forms of harassment while providing flexibility to accommodate diverse cultural contexts and individual sensibilities regarding appropriate workplace behavior and interpersonal interactions.

Comprehensive Protection Against Sexual Harassment Under Section 354A IPC

Section 354A represents one of the most significant legislative interventions addressing sexual harassment in India, introduced through the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 2013 following the horrific Delhi gang rape case that sparked nationwide outrage and demands for stronger protection against sexual violence. This provision defines sexual harassment as any man who commits physical contact and advances involving unwelcome and explicit sexual overtures, demands or requests for sexual favors, shows pornography against the will of a woman, or makes sexually colored remarks. The section recognizes multiple forms of sexual harassment rather than limiting itself to physical assault, thereby providing broader protection against various manifestations of sexual misconduct.

The punishment prescribed under Section 354A varies based on the nature of harassment. For unwelcome physical contact and advances, demands for sexual favors, or showing pornography against a woman’s will, the provision prescribes rigorous imprisonment which may extend to three years, or fine, or both. For making sexually colored remarks, the punishment includes imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to one year, or fine, or both. This graduated approach recognizes varying degrees of severity while ensuring that even verbal harassment carries criminal consequences, thereby addressing the continuum of sexual misconduct rather than focusing solely on the most serious offenses.

In workplace environments, Section 354A operates in conjunction with the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act of 2013, commonly known as the POSH Act. While the POSH Act provides a civil and administrative framework for addressing workplace sexual harassment through Internal Complaints Committees and redressal mechanisms, Section 354A offers criminal remedies for more serious instances of harassment. This dual framework ensures that victims have multiple avenues for seeking justice, ranging from organizational interventions to criminal prosecution depending on the severity and nature of the harassment faced.

The provision’s recognition of sexually colored remarks as a distinct category of harassment addresses a common form of workplace misconduct that often goes unreported due to normalization or fear of being labeled as oversensitive. Such remarks, which may include comments about physical appearance, sexual orientation, marital status, or inappropriate jokes with sexual connotations, create uncomfortable and hostile work environments that undermine professional relationships and career advancement. By criminalizing such behavior, Section 354A sends a clear message that sexual harassment in any form will not be tolerated and provides legal backing to organizational policies against such conduct.

Addressing Marital Cruelty Through Section 498A IPC

Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code, introduced through the Criminal Law (Second Amendment) Act of 1983, addresses cruelty against married women by their husbands or relatives of their husbands. This provision states that whoever, being the husband or the relative of the husband of a woman, subjects such woman to cruelty shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years and shall also be liable to fine. The explanation to this section defines cruelty as any willful conduct likely to drive the woman to commit suicide or to cause grave injury or danger to life, limb or health (whether mental or physical) of the woman, or harassment with a view to coercing her or any person related to her to meet any unlawful demand for property or valuable security.

The significance of Section 498A lies in its explicit recognition of mental cruelty as a form of domestic violence deserving criminal sanction. Before its introduction, cases of cruelty against wives were addressed through general provisions relating to assault or grievous hurt, which required proof of physical injury and failed to capture the psychological dimensions of domestic abuse. The provision acknowledges that systematic harassment, emotional abuse, and psychological torture within marital relationships can cause severe mental anguish and drive victims to desperate measures including suicide. By including mental health explicitly in the definition of cruelty, the legislature recognized that psychological violence can be as destructive as physical assault.

The scope of Section 498A extends beyond the husband to include his relatives, acknowledging the reality that in many Indian households, married women face harassment not just from their spouses but also from in-laws, particularly in joint family settings. This broader application addresses situations where the husband may not be the primary perpetrator but his family members subject the wife to continuous harassment, often related to dowry demands, inability to bear children, or failure to meet unrealistic expectations. The provision recognizes that domestic cruelty frequently involves multiple perpetrators and requires a systemic response rather than focusing solely on the husband-wife relationship.

The case of Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar [1] represents a landmark judgment that addressed concerns about misuse of Section 498A. The Supreme Court observed that while the provision serves a crucial protective function, it had increasingly been weaponized in matrimonial disputes, leading to harassment of husbands and their relatives through arbitrary arrests. The Court laid down guidelines requiring police officers to satisfy themselves about the genuineness and seriousness of allegations before making arrests, and directed magistrates to exercise caution in authorizing detention. This judgment reflects the judiciary’s attempt to balance protection of genuine victims with safeguards against malicious prosecution.

In another significant case, Manju Ram Kalita v. State of Assam [2], the Supreme Court emphasized that cruelty under Section 498A must be established in context rather than through isolated incidents. The Court held that petty quarrels and normal wear and tear of married life cannot be termed as cruelty attracting criminal liability. The judgment clarified that to constitute cruelty, the conduct must be of such nature as to be likely to drive the woman to commit suicide or cause grave injury to her life, limb, or health. This interpretation prevents trivial matrimonial disputes from being criminalized while ensuring that genuine cases of systematic harassment receive appropriate legal intervention.

The case of Rajesh Kumar v. State of Uttar Pradesh [3] led to further refinement of procedural safeguards to prevent misuse of Section 498A. The Supreme Court constituted Family Welfare Committees at district levels to examine complaints before arrests are made, though this direction was later modified in Social Action Forum for Manav Adhikar v. Union of India [4]. The Court recognized that while preventing misuse is important, overly restrictive procedures should not undermine the provision’s protective purpose or make it difficult for genuine victims to access justice. These judicial interventions demonstrate ongoing efforts to strike appropriate balance between victim protection and prevention of abuse of process.

Regulatory Framework and Complementary Legislation

The Indian Penal Code provisions addressing mental and workplace harassment operate within a broader regulatory framework that includes specialized legislation and constitutional protections. The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act of 2013 provides a specific framework for addressing workplace sexual harassment through preventive measures, complaints mechanisms, and redressal procedures. This Act mandates that organizations with ten or more employees must constitute Internal Complaints Committees to receive and investigate complaints, thereby creating institutional mechanisms for addressing harassment before it escalates to criminal proceedings.

The interplay between IPC provisions and the POSH Act creates a multi-layered approach to addressing workplace harassment. While the POSH Act provides civil and administrative remedies including warnings, censure, transfer, or termination of employment, IPC sections offer criminal sanctions including imprisonment and fines. This dual framework allows victims to choose appropriate remedies based on the severity of harassment and their desired outcomes. Organizations are required to inform employees about their rights under both frameworks and cannot prevent victims from pursuing criminal remedies even while internal complaints are being addressed.

Constitutional provisions, particularly Article 14 guaranteeing equality before law, Article 15 prohibiting discrimination on grounds of sex, and Article 21 protecting life and personal liberty, provide foundational support for laws addressing harassment. Courts have interpreted these provisions to include protection against mental torture and harassment as fundamental rights, thereby elevating harassment from a mere criminal offense to a constitutional violation. This constitutional dimension strengthens enforcement mechanisms and ensures that protection against harassment receives priority in policy formulation and judicial decision-making.

Labor legislation including the Industrial Employment (Standing Orders) Act, the Factories Act, and various state-specific labor laws also contain provisions addressing workplace conditions and employee welfare that intersect with harassment prevention. These laws empower labor commissioners and inspectors to investigate complaints about hostile work environments and unsafe conditions, providing additional institutional mechanisms for addressing harassment. The multiplicity of legal frameworks, while potentially creating complexity, ensures that victims have various avenues for seeking redress depending on their specific circumstances and needs.

Evidentiary Challenges and Documentation Requirements

Prosecuting cases under IPC provisions addressing mental and workplace harassment presents unique evidentiary challenges given the intangible nature of psychological harm. Unlike physical assault cases where injuries can be documented through medical examination, mental harassment requires establishing psychological impact through testimony, behavioral evidence, and expert opinions. Courts have recognized that in harassment cases, the victim’s testimony assumes particular significance and corroboration, while desirable, may not always be available given that such incidents often occur in private or in the absence of independent witnesses.

Documentation becomes crucial in establishing harassment claims, particularly in workplace contexts where formal communication channels exist. Emails, text messages, recorded conversations, and written complaints create documentary evidence that can substantiate allegations of harassment and demonstrate patterns of behavior rather than isolated incidents. Legal practitioners advise victims to maintain detailed records of harassment incidents including dates, times, locations, witnesses, and specific actions or statements, as such documentation significantly strengthens cases and helps overcome the challenge of proving mental distress.

Medical evidence including psychological assessments, treatment records, and expert testimony from mental health professionals can establish the impact of harassment on victims’ mental health. Courts have increasingly recognized conditions such as depression, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder as manifestations of mental cruelty and harassment, thereby validating psychological harm as worthy of legal protection and remedy. However, accessing such medical evidence requires victims to seek professional help, which many may be reluctant to do due to stigma, cost, or lack of awareness about its legal significance.

The role of witness testimony in harassment cases cannot be understated, as colleagues, friends, or family members who observed changes in the victim’s behavior or were confided in about the harassment can provide crucial corroboration. However, witnesses may be reluctant to come forward due to fear of retaliation, particularly in workplace harassment cases where testifying against colleagues or superiors might jeopardize their own positions. Courts have developed principles for assessing credibility and corroboration that recognize these practical difficulties while ensuring that genuine cases receive appropriate consideration and that fabricated allegations can be identified and dismissed.

Limitations and Scope for Reform

Despite the existence of various IPC provisions addressing mental and workplace harassment, significant gaps remain in the legal framework. The absence of a specific provision exclusively addressing mental harassment in non-marital relationships means that victims of harassment by partners in live-in relationships, dating relationships, or same-sex relationships may find existing provisions inadequate. Similarly, male victims of harassment face challenges in accessing legal protection as several provisions are gender-specific, reflecting societal assumptions about victimization that may not align with contemporary reality.

The procedural complexities involved in prosecuting harassment cases, including lengthy investigation periods, court backlogs, and the adversarial nature of criminal proceedings, can deter victims from pursuing legal remedies. The prospect of cross-examination, repeated court appearances, and potential counter-allegations creates significant psychological burden on complainants, particularly when harassment has already caused mental trauma. Reforms aimed at simplifying procedures, protecting victims during trials, and expediting disposal of cases could enhance the effectiveness of existing legal provisions in providing meaningful relief.

Concerns about misuse of harassment provisions, particularly Section 498A, have sparked debates about appropriate safeguards to prevent malicious prosecution while protecting genuine victims. The challenge lies in developing mechanisms that screen out frivolous complaints without creating insurmountable barriers for legitimate cases. Some commentators have suggested measures including penalties for false complaints, mandatory conciliation before criminal prosecution, or requiring complainants to provide security for costs. However, others argue that such measures could have chilling effects on reporting and shift focus from perpetrator accountability to victim verification.

The need for comprehensive anti-harassment legislation that consolidates various provisions, extends protection to all individuals regardless of gender or relationship status, and provides both preventive and remedial mechanisms has been widely recognized. Such legislation could incorporate best practices from international frameworks, establish specialized institutional mechanisms for addressing mental and workplace harassment, mandate training and awareness programs, and ensure that legal remedies are accessible, affordable, and effective. Until such reforms materialize, existing IPC provisions continue to serve as primary legal instruments for addressing mental and workplace harassment, despite their limitations and gaps.

Conclusion

The legal framework for addressing mental and workplace harassment in India, though fragmented across multiple provisions of the Indian Penal Code and complementary legislation, represents significant evolution in recognizing psychological harm as deserving legal protection and criminal sanction. Sections 503, 294, 509, 354A, and 498A provide various avenues for victims to seek redress against different forms of harassment, intimidation, and cruelty. These provisions acknowledge that harassment need not involve physical violence to constitute serious offenses and that psychological trauma can be as damaging as physical injury.

The judicial interpretation of these provisions through landmark judgments has shaped their practical application, establishing principles for determining what constitutes harassment, how evidence should be evaluated, and what safeguards are necessary to prevent misuse while protecting genuine victims. The ongoing tension between ensuring victim protection and preventing malicious prosecution reflects broader societal debates about gender relations, power dynamics, and appropriate boundaries in both personal and professional settings. As society evolves and new forms of harassment emerge, particularly in digital spaces, mental and workplace harassment laws in India must continually adapt to remain relevant and effective.

Understanding these legal provisions empowers individuals to recognize harassment, document incidents, and pursue appropriate remedies. Equally important is awareness among organizations, educational institutions, and employers about their responsibilities in preventing harassment and providing safe environments. The effectiveness of legal provisions ultimately depends not just on their existence but on their implementation through sensitized law enforcement, an accessible justice system, and a societal commitment to dignity and equality for all individuals regardless of gender, position, or relationship status.

References

[1] Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar, (2014) 8 SCC 273 – https://blog.ipleaders.in/top-5-supreme-court-judgment-on-misuse-of-498a/

[2] Manju Ram Kalita v. State of Assam, (2009) 13 SCC 330 – https://blog.ipleaders.in/top-5-supreme-court-judgment-on-misuse-of-498a/

[3] Rajesh Kumar v. State of Uttar Pradesh, (2017) SCC OnLine SC 821 – https://blog.ipleaders.in/top-5-supreme-court-judgment-on-misuse-of-498a/

[4] Social Action Forum for Manav Adhikar v. Union of India, Writ Petition (Criminal) No. 129 of 2013 – https://blog.ipleaders.in/top-5-supreme-court-judgment-on-misuse-of-498a/

[5] Indian Penal Code, 1860, Section 354A – https://lawrato.com/indian-kanoon/ipc/section-354a

[6] Indian Penal Code, 1860, Section 498A – https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_5_23_00037_186045_1523266765688&orderno=562

[7] Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 – https://lawrato.com/indian-kanoon/criminal-law/laws-related-to-mental-harassment-in-india-2835

[8] Mental Harassment at Workplace: Legal Framework – https://www.chambersofmohitsingh.in/blog/mental-harassment-at-workplace/

Overview of Workplace Harassment Act in India: The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 (POSH Act)

Introduction

The workplace should be a sanctuary of professional growth and dignity, yet for decades, women in India faced an invisible battle against sexual harassment that remained largely unaddressed by formal legal mechanisms. The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, commonly known as the POSH Act, emerged as a watershed legislative intervention that fundamentally transformed how workplace safety and dignity are protected in India. This landmark legislation, which received Presidential assent on April 23, 2013, and came into force on December 9, 2013, represents the culmination of years of advocacy, judicial intervention, and societal recognition of women’s fundamental right to work in an environment free from harassment [1].

The genesis of this Act lies in the recognition that sexual harassment at the workplace is not merely an interpersonal conflict but a violation of fundamental constitutional rights guaranteed under Articles 14, 15, 19(1)(g), and 21 of the Constitution of India. The Act extends to the whole of India and applies to all workplaces, whether organized or unorganized, in the public or private sector. What makes this legislation particularly significant is its attempt to create a preventive, prohibitory, and redressal framework that places the responsibility of ensuring safe workplaces squarely on employers while empowering women to seek justice without fear of retaliation.

The POSH Act, 2013 was enacted to address a critical legislative vacuum that existed despite India’s ratification of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1993. For nearly two decades before the Act’s enactment, workplaces in India were governed by the Vishaka Guidelines, which, while groundbreaking, lacked the enforcement mechanisms and statutory backing necessary for effective implementation [2]. The transition from judicially mandated guidelines to codified legislation marked a significant evolution in India’s commitment to workplace gender equality and women’s safety.

Historical Background and the Vishaka Guidelines

Understanding the POSH Act requires examining the historical context that necessitated its creation. The story begins with a heinous incident in 1992 when Bhanwari Devi, a social worker employed by the Government of Rajasthan’s Rural Development Programme, was gang-raped by five men from an upper-caste community while she was attempting to prevent a child marriage in her village. The brutal attack was an act of revenge for her efforts to stop the illegal practice. What followed was not just a legal battle but a social awakening to the pervasive reality of sexual harassment and violence against women in workplaces across India.

The incident prompted women’s rights organizations and activists to approach the Supreme Court of India through a public interest litigation. In the landmark case of Vishaka and Others v. State of Rajasthan (1997) [3], the Supreme Court recognized that the absence of domestic legislation on workplace sexual harassment violated India’s international obligations and constitutional mandate to protect women’s rights. The Court observed that sexual harassment at the workplace violates a woman’s fundamental right to gender equality under Articles 14 and 15, her right to life and to live with dignity under Article 21, and her right to practice any profession or carry on any occupation, trade, or business under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution.

In this historic judgment delivered on August 13, 1997, the Supreme Court laid down detailed guidelines known as the Vishaka Guidelines. These guidelines defined sexual harassment, mandated the creation of complaints committees in workplaces, outlined complaint procedures, and prescribed preventive measures. The Court explicitly stated that these guidelines would have the force of law until appropriate legislation was enacted by Parliament. The Vishaka Guidelines became the legal framework governing workplace sexual harassment for the next sixteen years, serving as the foundation upon which the POSH Act would eventually be built.

The Vishaka judgment was revolutionary for several reasons. First, it expanded the definition of workplace to include not just traditional office settings but any place visited by an employee during or arising out of employment. Second, it recognized that sexual harassment creates a hostile work environment and amounts to discrimination on the grounds of sex. Third, it placed affirmative obligations on employers to prevent and redress sexual harassment, moving beyond mere prohibition to active prevention. The judgment drew upon international conventions, particularly CEDAW, and utilized Article 253 of the Constitution, which permits Parliament to make laws for implementing international agreements, to justify the application of international standards in the absence of domestic legislation.

However, the Vishaka Guidelines, despite their legal force, faced significant implementation challenges. Many workplaces, particularly in the private sector and smaller establishments, either remained unaware of these guidelines or failed to establish the required complaints committees. The lack of statutory penalties for non-compliance meant that enforcement was inconsistent and often dependent on the willingness of individual organizations to take the guidelines seriously. These limitations underscored the urgent need for comprehensive legislation with clear definitions, wider applicability, stronger enforcement mechanisms, and prescribed penalties for violations.

Genesis and Enactment of the POSH Act, 2013

The journey from the Vishaka Guidelines to the enactment of the POSH Act, 2013 was neither swift nor straightforward. It took sixteen years of persistent advocacy by women’s groups, civil society organizations, legal experts, and progressive lawmakers to translate the spirit of the Vishaka Guidelines into statutory law. During this period, various draft bills were proposed, debated, and refined. The Protection of Women against Sexual Harassment at Workplace Bill was first introduced in the Rajya Sabha in 2010 but underwent several modifications based on feedback from stakeholders, parliamentary committees, and public consultations.

The Bill that would eventually become the POSH Act was introduced in the Lok Sabha and passed on September 3, 2012. It was subsequently passed by the Rajya Sabha on February 26, 2013, with certain amendments aimed at strengthening its provisions and expanding its scope. The Act received Presidential assent on April 23, 2013, and was officially notified as Act No. 14 of 2013 [4]. The implementation rules, known as the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Rules, 2013, were notified later that year, and the Act came into force on December 9, 2013.

The POSH Act consists of 32 sections divided into seven chapters, covering definitions, internal complaints mechanisms, district-level committees, inquiry procedures, penalties, and miscellaneous provisions. The Act superseded the Vishaka Guidelines, providing a more detailed and enforceable framework for preventing and addressing sexual harassment at workplaces. Unlike the Guidelines, which were judge-made law, the POSH Act derives its authority from parliamentary legislation, giving it greater legitimacy, wider acceptance, and stronger enforcement teeth.

One of the most significant aspects of the POSH Act is its inclusive definition of workplace and employee. The Act recognizes that modern employment relationships extend beyond traditional employer-employee dynamics and that women work in various capacities across diverse settings. Consequently, it applies to organized and unorganized sectors, public and private establishments, and covers women employees, workers, interns, volunteers, apprentices, and even those visiting workplaces for professional purposes. This expansive scope ensures that the protective umbrella of the Act extends to all women who may be vulnerable to sexual harassment in professional settings.

Defining Sexual Harassment Under the POSH Act, 2013

The POSH Act 2013 provides a comprehensive definition of sexual harassment, recognizing that such behavior manifests in various forms and may not always involve physical contact. Section 2(n) of the Act defines sexual harassment to include any one or more of the following unwelcome acts or behavior, whether directly or by implication: physical contact and advances, a demand or request for sexual favors, making sexually colored remarks, showing pornography, or any other unwelcome physical, verbal, or non-verbal conduct of a sexual nature.

Importantly, the Act specifies that unwelcome behavior is the cornerstone of sexual harassment. This means that the subjective feeling of the woman is paramount; if she perceives the conduct as unwelcome, it constitutes harassment regardless of the alleged harasser’s intent. This woman-centric approach marks a departure from traditional legal frameworks that often required proof of intent or malice, which were difficult to establish and placed unfair burdens on complainants.

The Act also recognizes certain circumstances where sexual harassment occurs even in the absence of explicit sexual conduct. These circumstances, outlined in Section 2(n), include situations where there is an implied or explicit promise of preferential treatment in employment, an implied or explicit threat of detrimental treatment in employment, an implied or explicit threat about the woman’s present or future employment status, interference with her work or creating an intimidating or offensive or hostile work environment, or humiliating treatment likely to affect her health or safety. This recognition that hostile work environments and quid pro quo harassment are equally serious forms of sexual harassment was groundbreaking and aligned Indian law with international best practices.

By providing such a detailed definition, the POSH Act ensures that various manifestations of sexual harassment are legally cognizable. It covers verbal harassment such as sexually explicit comments, jokes, or innuendos; non-verbal harassment including leering, making obscene gestures, or displaying pornographic material; and physical harassment ranging from unwelcome touching to more serious forms of sexual assault. The Act’s definition also recognizes that harassment can occur through electronic means, including emails, messages, or social media, acknowledging the evolving nature of workplace interactions in the digital age.

The definition’s emphasis on unwelcomeness is critical because it centers the experience of the aggrieved woman. What one person might perceive as harmless banter could be experienced by another as deeply offensive and threatening. The Act respects this subjective reality while providing an objective framework for adjudication. This balance ensures that women are not dismissed when they report uncomfortable experiences while also providing fair procedures for the accused to present their case.

Regulatory Framework and Institutional Mechanisms

The POSH Act, 2013 establishes a dual redressal mechanism comprising Internal Complaints Committees (ICC) at the workplace level and Local Complaints Committees (LCC) at the district level. This two-tier structure ensures that all women, regardless of their workplace size or organizational structure, have access to a forum where they can file complaints and seek redress.

Every employer of a workplace with ten or more employees is mandated to constitute an Internal Complaints Committee. The composition of the ICC is carefully prescribed to ensure impartiality, gender sensitivity, and inclusion of external expertise. The ICC must consist of a Presiding Officer who must be a woman employed at a senior level at the workplace, not less than two members from amongst employees preferably committed to the cause of women or who have experience in social work or have legal knowledge, and one external member from amongst NGOs or associations committed to the cause of women or a person familiar with issues relating to sexual harassment. Importantly, at least one-half of the total members must be women.

This composition serves multiple purposes. The requirement for a senior woman employee as Presiding Officer ensures that the person leading the inquiry has both organizational standing and an understanding of workplace dynamics. The inclusion of internal members provides institutional knowledge and context, while the external member brings objectivity, prevents potential conflicts of interest, and ensures that the process is not entirely controlled by the employer. The gender balance requirement ensures that women’s perspectives are adequately represented in the decision-making process.

For establishments with fewer than ten employees, or in cases where a woman is unable or unwilling to file a complaint with the Internal Committee, the Act provides for Local Complaints Committees at the district level. The District Officer is responsible for constituting the LCC, which has a similar composition to the ICC but operates independently of any specific workplace. The LCC plays a crucial role in ensuring that women working in smaller establishments, those in the unorganized sector, domestic workers, and women working in private homes as employees have access to a complaints mechanism.

Both the ICC and LCC are vested with the same powers as those vested in a civil court under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, when dealing with certain matters. These powers include summoning and enforcing the attendance of any person and examining them on oath, requiring the discovery and production of documents, and any other matter which may be prescribed. This grant of quasi-judicial powers ensures that complaints committees can conduct thorough investigations and that parties cannot refuse to cooperate with the inquiry process.

The Act mandates that every employer must provide all necessary facilities to the ICC for dealing with complaints and conducting inquiries. This includes providing a safe and confidential space for conducting hearings, ensuring that the complainant and witnesses are not intimidated or retaliated against, and making available such other facilities as may be prescribed. Employers are also required to organize orientation and awareness programs at regular intervals for sensitizing employees about the provisions of the Act and organizing workshops and seminars for members of the ICC. These preventive measures are essential for creating a culture of respect and dignity in workplaces.

The Act also addresses the issue of interim relief for complainants during the pendency of inquiry. Upon receiving a complaint, the ICC or LCC may recommend to the employer measures such as transferring the complainant or the respondent to any other workplace, granting leave to the complainant, or restraining the respondent from reporting on the work performance of the complainant or writing confidential reports. These provisions recognize that the inquiry process may take time and that the complainant should not be forced to continue working in a hostile environment or facing potential retaliation while the complaint is under investigation.

Complaint and Inquiry Procedures under the POSH Act

The POSH Act, 2013 prescribes detailed procedures for filing complaints and conducting inquiries, ensuring that the process is fair, transparent, and efficient. Any aggrieved woman may make a complaint of sexual harassment in writing to the ICC or LCC within a period of three months from the date of the incident. In cases where a series of incidents occur, the complaint must be filed within three months from the date of the last incident. The Act recognizes that in certain situations, women may not be able to file complaints themselves, and therefore permits complaints to be made on behalf of the aggrieved woman by her legal heir in case of her death or mental or physical incapacity, or by any person who has knowledge of the incident with the written consent of the aggrieved woman.

The three-month limitation period has been a subject of discussion, with some arguing that it may be insufficient given that women may take time to process traumatic experiences, fear retaliation, or initially attempt informal resolution. However, the Act does provide that the ICC or LCC may extend this period by another three months if they are satisfied that circumstances prevented the complainant from filing the complaint within the initial period. This flexibility ensures that genuine cases are not dismissed on technical grounds while also providing some certainty and closure.

Upon receiving a complaint, the ICC or LCC must send a copy to the respondent within seven working days. The respondent is then given an opportunity to submit a written response within ten working days of receipt. This ensures that principles of natural justice are followed and that the accused has adequate opportunity to understand the allegations and prepare a defense. The Act mandates that the ICC or LCC must complete the inquiry within a period of ninety days from the date of receipt of the complaint.

Before initiating the inquiry, the Act provides for an important mechanism of conciliation at the request of the complainant. However, this conciliation process cannot involve any monetary settlement and must be handled sensitively to ensure that the complainant is not pressured into withdrawal. If a settlement is reached through conciliation, the ICC or LCC records the settlement and provides copies to both parties, and no further inquiry is conducted. If the settlement terms are not complied with, the ICC or LCC may proceed with the inquiry or take action as recommended. This provision recognizes that in some cases, particularly those involving misunderstandings or less serious offenses, reconciliation may be appropriate and preferred by the complainant.

During the inquiry process, both parties are given an opportunity to be heard and present their case. The inquiry must be conducted in accordance with principles of natural justice, ensuring fairness, impartiality, and due process. The ICC or LCC has the discretion to call witnesses, examine documents, and seek expert opinions as necessary for arriving at a just conclusion. The Act specifically mandates that the identity of the complainant, respondent, witnesses, and all information relating to conciliation and inquiry proceedings must be kept confidential. This confidentiality provision is crucial for protecting the dignity and privacy of all parties involved and for encouraging women to come forward without fear of public humiliation or retaliation.

The Act also addresses situations where complaints may be false or malicious. While emphasizing that the mere inability to substantiate a complaint or provide adequate proof does not amount to a false or malicious complaint, the Act provides that if the ICC or LCC arrives at a conclusion that the allegation was false or malicious or made with a mischievous intent, it may recommend action against the complainant. However, such a finding must be based on concrete evidence and cannot be made merely because the complaint could not be proved. This balance ensures that women are not deterred from filing genuine complaints while also protecting against deliberate misuse of the law.

Recommendations, Actions, and Enforcement

Upon completion of the inquiry, the ICC or LCC prepares an inquiry report within ten days, which must be made available to the concerned parties. If the inquiry reveals that the allegation of sexual harassment is proved, the Committee makes recommendations for action to be taken against the respondent. For employees, this may include written apology, warning, reprimand, withholding of promotion, withholding of pay rise or increments, termination from service, undergoing counseling, or carrying out community service. For respondents who are not employees, the Committee may recommend appropriate action according to the provisions of service rules applicable to them.

In cases where sexual harassment amounts to an offense under the Indian Penal Code or any other law, the ICC or LCC may recommend initiation of criminal action. This provision recognizes that some forms of sexual harassment are also criminal offenses such as assault, criminal intimidation, or stalking, and that civil remedies under the POSH Act do not preclude criminal prosecution. The employer or District Officer, as the case may be, is mandated to implement the recommendations within sixty days of their receipt and inform the ICC or LCC about the action taken.

The Act also provides for compensation to be awarded to the aggrieved woman. If the ICC or LCC arrives at the conclusion that the allegation is proved, it may recommend payment of compensation to the complainant by the respondent. The compensation should be determined based on the mental trauma, pain, suffering, and emotional distress caused to the complainant, the loss of career opportunity arising from the incident, medical expenses incurred by the victim for physical or psychiatric treatment, the income and financial status of the respondent, and feasibility of such payment. The employer must facilitate payment of this compensation, which can be recovered as an arrear of land revenue if not paid.

The POSH Act prescribes penalties for non-compliance with its provisions, making it one of the few gender-specific laws with built-in enforcement mechanisms. If any employer fails to constitute an ICC, the penalty is a fine up to fifty thousand rupees. For subsequent contraventions of the same provision, the fine may extend to one lakh rupees. Similarly, contravention of other provisions of the Act, such as not providing necessary facilities to the ICC, not assisting in securing attendance of respondent and witnesses, not making available necessary information to the ICC or LCC, or discharging or otherwise discriminating against the complainant, attracts penalties ranging from ten thousand to fifty thousand rupees.

The Act designates the appropriate government to appoint or authorize any officer to be the competent authority to ensure compliance. This officer has the power to inspect workplace records, recommend prosecution for violations, and monitor implementation of the Act’s provisions. The District Officer is specifically tasked with ensuring compliance with the Act at the district level, particularly regarding the constitution and functioning of Local Complaints Committees. State governments are required to submit annual reports to the central government on the number of cases filed and their disposal, providing a mechanism for monitoring nationwide implementation.

Landmark Judicial Pronouncements

Since the enactment of the POSH Act, several judicial pronouncements have interpreted its provisions and clarified its application, building upon the foundation laid by the Vishaka judgment. These cases have addressed various aspects of the law, from definitional issues to procedural requirements, and have played a crucial role in shaping the practical implementation of workplace sexual harassment laws in India.

In the case of Medha Kotwal Lele v. Union of India and Others (2013) [5], which was decided just before the POSH Act came into force, the Supreme Court directed all states and union territories to implement the Vishaka Guidelines strictly until the new legislation was brought into effect. The Court expressed concern over the lack of compliance with the Guidelines and emphasized the government’s constitutional obligation to protect women’s rights. The judgment reinforced that judicial guidelines have the force of law and that authorities cannot take a casual approach to their implementation. The Court’s proactive stance in this case demonstrated the judiciary’s commitment to ensuring that women’s workplace safety was not compromised during the transition from guidelines to statutory law.

The Supreme Court case of Aureliano Fernandes v. State of Goa and Others (2023) [6] provided crucial directions for effective implementation of the POSH Act. The Court observed that despite the Act being in force for nearly a decade, many establishments had not constituted Internal Complaints Committees or were not functioning effectively. The judgment directed all state governments to ensure strict compliance with the Act and to take action against employers who failed to constitute ICCs. The Court also emphasized the need for regular training of ICC members and awareness programs for employees. This judgment was significant for recognizing that the mere enactment of legislation is insufficient without robust implementation mechanisms and government oversight.

In various High Court decisions across India, courts have addressed specific issues arising under the POSH Act. Courts have held that the definition of workplace extends beyond traditional office premises to include locations such as client sites, transportation provided by employers, and even social events organized by the employer. This expansive interpretation ensures that women are protected wherever their professional duties take them. Courts have also clarified that the three-month limitation period for filing complaints should be interpreted liberally, particularly in cases involving power imbalances or where the complainant faced threats or intimidation that delayed her complaint.

Judicial pronouncements have also emphasized the importance of maintaining confidentiality during inquiry proceedings. Courts have held that unauthorized disclosure of the complainant’s identity or inquiry details amounts to a violation of the Act and can attract contempt proceedings. This protection is essential for encouraging women to file complaints without fear of public exposure or character assassination. At the same time, courts have balanced this with the respondent’s right to a fair hearing, ensuring that confidentiality does not compromise due process.

Courts have also addressed the relationship between proceedings under the POSH Act and criminal proceedings under the Indian Penal Code. It has been consistently held that civil remedies under the POSH Act and criminal prosecution can proceed simultaneously; one does not bar the other. However, if criminal charges are filed, the ICC or LCC inquiry may be stayed pending the outcome of the criminal case, particularly if the accused demonstrates that proceeding with both simultaneously would prejudice their defense. This nuanced approach recognizes the different purposes served by civil and criminal proceedings while preventing harassment through multiple proceedings.

Challenges in Implementation of the POSH Act

Despite the robust legal framework established by the POSH Act,2013 its implementation faces several challenges that limit its effectiveness in achieving the goal of workplace safety for women. One of the primary challenges is awareness. Many workplaces, particularly small and medium enterprises and those in the unorganized sector, remain unaware of their obligations under the Act. Women employees in such establishments often do not know their rights or the existence of redressal mechanisms. This information gap is especially pronounced in rural areas and among women with lower educational backgrounds or those engaged in informal employment.

Compliance with the requirement to constitute Internal Complaints Committees remains inconsistent. While larger corporations and government establishments generally have ICCs in place, smaller private sector establishments frequently fail to constitute committees or constitute them only on paper without actual functionality. The lack of regular monitoring and enforcement by competent authorities allows non-compliance to persist. Even where ICCs exist, their effectiveness varies significantly depending on the commitment of the organization, the training provided to committee members, and the organizational culture regarding gender issues.

The quality of inquiries conducted by ICCs and LCCs is another area of concern. Many committee members lack proper training in conducting sensitive inquiries, understanding trauma-informed approaches, or applying legal principles of evidence and natural justice. This can result in inquiries that are either too lenient, failing to establish harassment even when it occurred, or too harsh, violating the respondent’s right to fair hearing. The quasi-judicial nature of ICC proceedings requires a delicate balance between being victim-centric and ensuring due process, which untrained members may struggle to maintain.

Fear of retaliation remains a significant barrier to women filing complaints. Despite the Act’s provisions prohibiting retaliation and providing for interim relief, many women fear that complaining will jeopardize their careers, result in isolation at work, or lead to hostile treatment from colleagues. This fear is particularly acute when the alleged harasser is a superior or someone in a position of power within the organization. While the Act provides legal protection, changing organizational culture to genuinely support complainants requires sustained effort beyond legal compliance.

The provision regarding Local Complaints Committees, while important for covering smaller establishments, faces serious implementation challenges. Many districts have not constituted LCCs or have done so without adequate resources, infrastructure, or trained personnel. Women who might want to approach LCCs often do not know where to find them or how to access them. The lack of dedicated resources for LCCs means that they cannot function effectively as parallel redressal mechanisms for women in smaller workplaces or the unorganized sector.

Another challenge relates to the intersection of the POSH Act with other labor laws and organizational practices. Questions arise about how sexual harassment complaints should be handled when they involve workers governed by different service rules, contract employees, or third-party vendors. The Act’s applicability to various employment relationships is sometimes unclear in practice, leading to situations where women fall through the cracks because of jurisdictional confusion.

The Road Ahead for the POSH Act, 2013

The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplac e (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, represents a significant milestone in India’s journey toward gender equality and workplace safety. It transforms the judicial innovation of the Vishaka Guidelines into a robust statutory framework with clear obligations, procedures, and enforcement mechanisms. However, the journey from legislative enactment to effective implementation and cultural transformation is ongoing and requires sustained commitment from all stakeholders.

Moving forward, several measures are necessary to strengthen the Act’s implementation and effectiveness. First, there must be a concerted effort to increase awareness about the Act among both employers and employees across all sectors. Government agencies, civil society organizations, and industry associations must collaborate to conduct widespread sensitization programs, particularly targeting smaller enterprises and the unorganized sector. Such programs should not merely explain legal compliance requirements but should focus on building understanding of what constitutes sexual harassment, why it violates fundamental rights, and how everyone in the workplace has a role in preventing it.

Second, capacity building for ICC and LCC members is essential. Standardized training modules should be developed and mandated for all committee members, covering areas such as gender sensitivity, understanding power dynamics, trauma-informed inquiry techniques, principles of natural justice, and confidentiality. Regular refresher training should be required to ensure that committee members remain updated on evolving jurisprudence and best practices. The government could consider creating a certification system for ICC members to ensure minimum standards of competence.

Third, enforcement mechanisms must be strengthened. The designated competent authorities under the Act need adequate resources and support to conduct regular audits of workplace compliance. The penalties for non-compliance, while significant on paper, are often not imposed in practice because of lack of monitoring. Creating dedicated cells within labor departments or women and child development departments specifically for POSH Act enforcement would demonstrate government commitment and facilitate better compliance.

Fourth, the collection and publication of data on sexual harassment complaints, inquiries, and their outcomes is crucial for understanding the Act’s impact and identifying areas for improvement. Currently, data collection is inconsistent, and even when data is collected, it is rarely made public or analyzed systematically. Transparent reporting would help identify patterns, assess whether penalties are being imposed consistently, and determine if certain sectors or types of workplaces have particular challenges that need targeted interventions.

Fifth, there should be periodic review of the Act’s provisions to address emerging challenges. For instance, the rise of remote work and virtual workplaces raises questions about how sexual harassment in digital spaces should be addressed. The applicability of the Act to gig economy workers and platform-based employment relationships is another area that may require clarification. As work arrangements evolve, the law must adapt to ensure that all women remain protected regardless of how or where they work.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there must be a focus on prevention rather than merely responding to complaints. While having robust redressal mechanisms is essential, the ultimate goal should be to create workplaces where sexual harassment does not occur. This requires fundamental shifts in organizational culture, gender sensitization at all levels, clear messaging from leadership about zero tolerance for harassment, and accountability structures that make prevention everyone’s responsibility. Employers must move beyond viewing POSH compliance as a legal checkbox to recognizing it as a core component of creating healthy, productive, and equitable workplaces.

Conclusion

The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, stands as a testament to the power of sustained advocacy, judicial innovation, and legislative commitment to gender justice. From the tragic incident involving Bhanwari Devi to the landmark Vishaka Guidelines and finally to comprehensive legislation, the journey reflects India’s evolving understanding of women’s rights and workplace dignity. The Act provides a framework that is both preventive and remedial, placing clear obligations on employers while empowering women to seek redress without fear.

Yet, the true measure of the Act’s success lies not in its provisions but in its implementation and the cultural change it engenders. Laws alone cannot eliminate sexual harassment; they must be accompanied by genuine commitment from organizations, awareness among all workplace participants, effective enforcement by authorities, and a societal recognition that women’s right to work with dignity is non-negotiable. The POSH Act provides the tools; it is now incumbent upon all stakeholders to use these tools effectively to create workplaces where every woman can pursue her professional aspirations without fear of harassment or discrimination.

As India continues its journey toward becoming a more inclusive and equitable society, the effective implementation of the POSH Act will remain a crucial indicator of our commitment to women’s rights and gender justice. The Act is not merely about handling complaints; it is about building a culture of respect, dignity, and equality in every workplace across the nation. This cultural transformation, more than any legal provision, will be the Act’s lasting legacy.

References

[1] Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India. (2013). The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2104

[2] Department of Women and Child Development, Delhi Government. Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013. Available at: https://wcd.delhi.gov.in/wcd/sexual-harassment-women-workplaceprevention-prohibition-and-redressal-act-2013sh-act-2013

[3] Vishaka and Others v. State of Rajasthan, AIR 1997 SC 3011. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1031794/

[4] Wikipedia. (2025). Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sexual_Harassment_of_Women_at_Workplace_(Prevention,_Prohibition_and_Redressal)_Act,_2013

[5] India Corporate Law. (2023). Supreme Court’s landmark ruling: Directions for effective implementation of the POSH Act. Available at: https://corporate.cyrilamarchandblogs.com/2023/06/supreme-courts-landmark-ruling-directions-for-effective-implementation-of-the-posh-act/

[6] LegalOnus. (2025). Landmark Cases and Evolution of POSH Act. Available at: https://legalonus.com/landmark-cases-and-evolution-of-posh-act/

[7] iPleaders. (2025). Vishaka & Ors. vs. State of Rajasthan & Ors. (1997). Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/vishaka-ors-vs-state-of-rajasthan-ors-1997/

[8] Ungender. (2024). Everything you need to know about Vishaka Guidelines. Available at: https://www.ungender.in/here-is-everything-you-need-to-know-about-vishaka-guidelines/

[9] POSH at Work. (2024). Judicial precedents leading to the implementation of POSH Act. Available at: https://poshatwork.com/judicial-precedents-leading-to-the-implementation-of-posh-act/

Published and Authorized by Rutvik Desai

Income Tax Department Imposes ₹23 Crore Penalty on ACC Limited: A Comprehensive Analysis of Tax Compliance and Penalty Provisions

Introduction

The Income Tax Department recently imposed a substantial penalty totaling ₹23.07 crore on ACC Limited, one of India’s leading cement manufacturing companies currently owned by the Adani Group. This enforcement action involves two separate penalty orders pertaining to Assessment Years 2015-16 and 2018-19, both predating the company’s acquisition by the Adani conglomerate.[1] The penalties stem from alleged violations related to furnishing inaccurate particulars of income and under-reporting of income, highlighting the stringent compliance requirements under Indian tax legislation. This case underscores the critical importance of accurate financial reporting and the severe consequences that corporate entities face when tax authorities identify discrepancies in their income declarations.

The penalties were imposed on October 1, 2025, affecting periods when ACC Limited was still under the ownership of Switzerland’s Holcim Group, before its acquisition by the Adani Group in September 2022 in a significant $6.4 billion transaction.[1] ACC Limited has announced its intention to contest both tax penalty orders before the Commissioner of Income Tax (Appeals) while simultaneously seeking a stay on the penalty demands. The company maintains that these penalties will not impact its ongoing financial operations, given its substantial revenue base of ₹21,762 crore in Financial Year 2024-25, with cement sales volume reaching 39 million tonnes.[1]

Background of the Tax Penalty Imposition on ACC Limited