Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

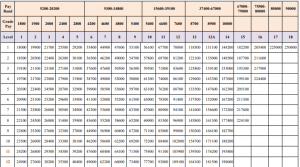

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

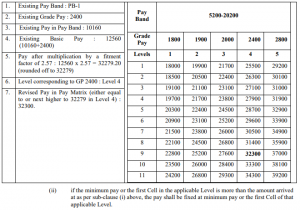

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

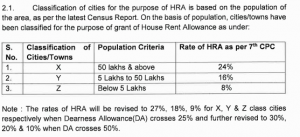

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

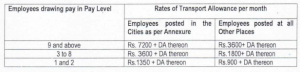

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Family Pension Rights of Railway Employees: A Comprehensive Analysis of Supreme Court’s Landmark Judgment in Mala Devi v. Union of India

Introduction

The Supreme Court of India’s recent judgment in Mala Devi v. Union of India [1] has brought significant clarity to family pension rights of railway employees, particularly those in non-permanent positions. This landmark decision, delivered on July 17, 2025, by a bench comprising Justice Sanjay Karol and Justice Satish Chandra Sharma, addresses the critical issue of family pension entitlements for widows of deceased railway employees who served as temporary or substitute workers.

The case highlights the ongoing challenges faced by families of railway employees who dedicated their lives to serving the nation but were denied pension benefits due to technicalities in service regulations. The court’s decision reflects a progressive interpretation of social welfare legislation and emphasizes the importance of substantive justice over procedural formalities.

Legal Framework Governing Railway Pension Rights

Railway Services (Pension) Rules, 1993

The Railway Services (Pension) Rules, 1993 [2] form the cornerstone of pension administration for railway employees in India. These rules were formulated to provide comprehensive guidelines for the grant of pension and other retirement benefits to railway servants and their families. The rules recognize various categories of railway employees and establish specific criteria for pension eligibility.

Rule 75 of the Railway Services (Pension) Rules, 1993 specifically addresses family pension entitlements. According to this rule, “In the event of death in harness of a railway servant who had completed one year of continuous service, the family of the deceased shall be entitled to family pension.” This provision establishes the fundamental principle that families of railway employees who die while in service are entitled to pension benefits, subject to certain qualifying conditions.

The rules also distinguish between different categories of railway employees, including permanent employees, temporary employees, and substitute employees. Each category has specific provisions governing their pension rights, with the underlying principle being to provide social security and uphold the family pension rights of railway employees who have served the railways with dedication and commitment.

Indian Railway Establishment Manual

The Indian Railway Establishment Manual [3] provides detailed guidelines for the administration of railway personnel policies. Rule 1515 of this manual specifically addresses the rights and privileges of substitute employees. It states that “Substitutes should be afforded all the rights and privileges as may be admissible to temporary railway servants, from time to time on completion of four months continuous service.”

This provision is crucial as it establishes the principle of parity between substitute employees and temporary railway servants. The manual recognizes that substitute employees, despite their nomenclature, perform the same duties and responsibilities as regular employees and therefore deserve similar treatment in terms of benefits and privileges.

The manual also outlines the screening and regularization process for substitute employees, emphasizing that those who successfully complete the prescribed screening procedures and demonstrate satisfactory performance should be considered for regularization. This process ensures that deserving substitute employees are not discriminated against merely due to their initial appointment status.

Case Background and Factual Matrix

The Appellant’s Circumstances

Mala Devi, the appellant in this case, was the widow of a substitute Porter who was appointed by the Indian Railways in 1986. Her husband was subsequently posted as a Guard/Shuntman at Garhara station after undergoing the mandatory medical screening process. The deceased employee served diligently for more than nine years and eight months before passing away while in service in 1996.

The significance of the deceased employee’s service cannot be understated. He had successfully completed the initial screening process, which included medical fitness tests and performance evaluations. His appointment as a Guard/Shuntman, a position of responsibility within the railway system, demonstrates that he was a trusted and capable employee who contributed meaningfully to railway operations.

Following her husband’s death, Mala Devi was appointed as a Substitute Gangman on compassionate grounds, which itself is a recognition of her husband’s service and her family’s contribution to the railway system. She was later regularized in this position, indicating that the railway administration recognized her capability and the legitimacy of her family’s connection to the railway service.

Administrative Rejection and Legal Challenges

Despite her husband’s substantial service and her own subsequent employment with the railways, Mala Devi’s application for family pension was rejected by the railway administration. The rejection was based on two primary grounds: first, that her husband had not completed the mandatory ten-year qualifying service period, falling short by approximately three months; and second, that he was never formally regularized during his lifetime.

This rejection led to a prolonged legal battle that spanned multiple judicial forums. The Central Administrative Tribunal, Patna Bench, initially dismissed her application in 2015, upholding the railway administration’s decision. The tribunal’s reasoning was primarily technical, focusing on the strict interpretation of service rules without considering the broader principles of social justice and equity.

The Patna High Court subsequently upheld the tribunal’s decision in 2016, further complicating Mala Devi’s quest for justice. The High Court’s decision reflected a narrow interpretation of the pension rules, emphasizing literal compliance with service requirements rather than considering the substantive contribution of the deceased employee.

Supreme Court’s Legal Analysis

Interpretation of Rule 75

The Supreme Court’s analysis began with a detailed examination of Rule 75 of the Railway Services (Pension) Rules, 1993. The Court emphasized that this provision clearly states a temporary railway servant becomes eligible for family pension after completing just one year of continuous service. This interpretation is crucial, as it affirms that the ten-year qualifying service often cited by administrative authorities does not apply uniformly to all categories of employees. In doing so, the Court reinforced the legal foundation for safeguarding the family pension rights of railway employees, particularly those in temporary or substitute roles.

The court’s interpretation reflects a purposive approach to statutory construction, where the intent and spirit of the legislation are given precedence over rigid literal interpretation. The judges recognized that the rule was designed to provide social security to families of railway employees who had made meaningful contributions to the railway system, regardless of their formal employment status.

Assessment of Substitute Employee Rights

The Supreme Court carefully examined the status of substitute employees within the railway system. The court noted that Rule 18(3) of the Pension Rules specifically addresses the treatment of substitute employees, equating them with temporary railway servants for pension purposes. This provision ensures that substitute employees are not discriminated against merely because of their initial appointment category.

The court emphasized that the deceased employee had successfully completed the screening process and had been performing his duties satisfactorily for over nine years. This performance record, combined with his successful completion of medical fitness tests and assignment to a responsible position, demonstrated that he was effectively functioning as a regular railway employee despite his technical classification as a substitute.

Critique of Administrative Approach

The Supreme Court strongly criticized the railway administration’s approach to denying pension benefits. The court observed that “the denial of family pension from her deceased husband for not completing 10 years of qualifying service by falling short of hardly 3 months, is not in congruence with the legislative intent of the Indian Railway Establishment Manual & the Railway Pension Rules, 1993.”

This criticism highlights the court’s concern with the mechanical application of rules without considering the underlying principles of social justice and equity. The court emphasized that the deceased employee’s service of over nine years and eight months represented a substantial contribution to the railway system, and denying pension benefits for a shortfall of three months defeated the very purpose of social welfare legislation.

Judicial Reasoning and Legal Principles

Social Welfare Legislation Interpretation

The Supreme Court’s judgment reflects a broader philosophy regarding the interpretation of social welfare legislation. The court emphasized that such legislation should be interpreted liberally to achieve its intended social objectives. The judges noted that “the salutary purpose of the rules thereunder is to extend the benefit of family pension to the families of those servants who have served for a considerable strength of time.”

This approach aligns with established jurisprudence that recognizes social welfare legislation as remedial in nature, designed to protect vulnerable sections of society. The court’s emphasis on the “salutary purpose” of pension rules underscores the importance of considering the broader social objectives of such legislation rather than focusing solely on technical compliance.

Substantive Justice Over Procedural Formalities

The judgment demonstrates the Supreme Court’s commitment to substantive justice over procedural formalities. The court recognized that while the deceased employee may not have been formally regularized, he had effectively performed the duties of a regular railway employee for an extended period. The court noted that “it is an admitted factum that the deceased had reached the necessary stage of scrutiny/screening for regularization of the post, and had been carrying out his services, literally till his last breath.”

This approach reflects the court’s understanding that justice should not be sacrificed at the altar of technical procedural requirements. The emphasis on the deceased employee’s continuous service and satisfactory performance highlights the court’s focus on substantive contribution rather than formal categorization.

Critique of Narrow Interpretation

The Supreme Court specifically criticized the narrow interpretation adopted by lower courts and administrative authorities. The court observed that such a narrow approach “defeats the spirit of social welfare legislation” and fails to achieve the intended objectives of pension rules. The judges emphasized that the employee, having served with the Railways for a substantial period before dying in harness, could not be excluded from posthumous benefits merely due to technical deficiencies in his service record.

This critique reflects the court’s broader concern with the tendency of administrative authorities to adopt overly restrictive interpretations of beneficial legislation. The court’s emphasis on the “spirit of social welfare legislation” underscores the importance of considering the broader social objectives of such laws rather than focusing solely on technical compliance.

Regulatory Framework and Implementation

Pension Administration Mechanism

The administration of railway pension benefits involves multiple layers of authority and oversight. The Railway Board, as the apex body, issues guidelines and clarifications regarding pension policies. These guidelines are then implemented by various railway zones and divisions through their respective pension disbursing agencies.

The current system requires pension cases to be processed through the concerned railway administration, which verifies service records, calculates pension amounts, and ensures compliance with applicable rules. However, the complexity of this system often leads to delays and disputes, particularly in cases involving temporary or substitute employees whose service records may be incomplete or ambiguous.

Challenges in Implementation

The implementation of pension rules faces several challenges, particularly in cases involving temporary or substitute employees. Service records for such employees may be incomplete or scattered across different administrative units. The lack of standardized procedures for verifying service periods and determining eligibility often leads to inconsistent decisions and prolonged disputes.

The Supreme Court’s judgment in Mala Devi’s case highlights the need for more streamlined and equitable procedures for processing pension claims. The court’s emphasis on substantive justice over procedural formalities suggests that administrative authorities should adopt a more flexible approach to pension administration, particularly in cases involving long-serving employees who may have been affected by administrative inefficiencies.

Implications and Future Directions

Impact on Railway Employee Rights

The Supreme Court’s judgment has significant implications for the rights of railway employees and their families. The decision establishes important precedents regarding the treatment of substitute and temporary employees, ensuring that they receive equitable treatment in pension matters. The court’s emphasis on the one-year qualifying service requirement for temporary employees, as opposed to the ten-year requirement for permanent employees, provides clarity and protection for vulnerable categories of railway workers.

The judgment also reinforces the principle that social welfare legislation should be interpreted liberally to achieve its intended objectives. This approach is likely to influence future cases involving pension disputes and may encourage administrative authorities to adopt more equitable approaches to benefit administration.

Administrative Reforms

The judgment suggests the need for comprehensive administrative reforms in pension administration. Railway authorities should review existing procedures to ensure that they align with the Supreme Court’s interpretation of pension rules. This may involve updating administrative guidelines, training personnel on the proper interpretation of social welfare legislation, and establishing more streamlined procedures for processing pension claims.

The court’s criticism of the narrow interpretation adopted by administrative authorities also suggests the need for greater sensitivity to the social objectives of pension legislation. Training programs for administrative personnel should emphasize the importance of considering the broader social context of pension rules rather than focusing solely on technical compliance.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s judgment in Mala Devi v. Union of India represents a significant milestone in the protection of family pension rights of railway employees. The decision demonstrates the court’s commitment to substantive justice and its willingness to interpret social welfare legislation in a manner that achieves its intended objectives. The judgment provides important guidance for administrative authorities and establishes clear principles for the treatment of temporary and substitute railway employees.

The case also highlights the ongoing challenges faced by families of railway employees in securing their rightful pension benefits. The court’s award of ex gratia compensation to Mala Devi recognizes the hardship caused by prolonged litigation and administrative delays. This aspect of the judgment serves as a reminder to administrative authorities of their responsibility to process pension claims efficiently and equitably.

The judgment’s emphasis on the “spirit of social welfare legislation” provides a framework for future cases involving pension disputes. It encourages a more holistic approach to benefit administration that considers the broader social objectives of such legislation rather than focusing solely on technical compliance. This approach is likely to benefit numerous railway employees and their families who have faced similar challenges in asserting their family pension rights.

References

[1] Mala Devi v. Union of India & Ors., 2025 INSC 855, Supreme Court of India.

[2] Railway Services (Pension) Rules, 1993, Ministry of Railways, Government of India. Available at: https://railwayrule.com/the-railway-services-pension-rules-1993

[3] Indian Railway Establishment Manual, Railway Board, Ministry of Railways. Available at: https://indianrailwayemployee.com/content/indian-railways-establishment-manual-irem

[4] Railway Services (Pension) Second Amendment Rules, 2024, Ministry of Railways. Available at: https://www.gconnect.in/orders-in-brief/railways-orders-in-brief/railway-services-pension-second-amendment-rules-2024-invalid-pension.html

[5] Supreme Court of India Official Website. Available at: https://www.sci.gov.in/

[6] AdvocateKhoj Legal Database, Supreme Court Judgments. Available at: https://www.advocatekhoj.com/library/judgments/announcement.php

Edited and Authorized by Vishal Davda

The Powers of the Enforcement Directorate: Constitution, Purpose and Alleged Political Misuse in Financial Crime Cases

Introduction: The Enforcement Directorate’s Growing Significance in India’s Financial Crime Framework

The Enforcement Directorate (ED) has emerged as one of India’s most powerful and controversial investigative agencies, wielding extensive powers under several financial crime statutes. Established on May 1, 1956, as a specialized enforcement unit, the ED has evolved from a modest agency handling foreign exchange violations to a formidable financial intelligence organization with sweeping powers to investigate, arrest, attach properties, and prosecute complex economic crimes.

Operating under the Department of Revenue, Ministry of Finance, the ED’s primary mandate centers on enforcing three key legislations: the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA), the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999 (FEMA), and the Fugitive Economic Offenders Act, 2018 (FEOA). However, it is the agency’s powers under PMLA that have generated the most significant legal and constitutional debates, particularly regarding its alleged misuse for political purposes.

Historical Evolution and Constitutional Framework

Genesis and Early Development

The origins of the Enforcement Directorate trace back to the post-independence era when India faced significant challenges in managing foreign exchange reserves and preventing capital flight. Initially established as an “Enforcement Unit” within the Department of Economic Affairs, the organization was created to handle violations under the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, 1947 (FERA ’47).

The unit’s early structure was modest, comprising a Legal Service Officer as Director of Enforcement, an officer from the Reserve Bank of India, and three inspectors from the Special Police Establishment, with branches in Mumbai and Calcutta. This humble beginning would eventually transform into a multi-disciplinary organization with 49 offices across India and over 2,000 officers.

Legislative Expansion of Powers

The powers of the Enforcement Directorate underwent significant expansion through successive legislative amendments:

1973-1999: The FERA Era During this period, FERA 1973 replaced its 1947 predecessor, granting the ED broader regulatory powers over foreign exchange transactions. The agency primarily functioned as a civil enforcement body with limited criminal jurisdiction.

2000-2002: Transition to FEMA and Introduction of PMLA The economic liberalization of the 1990s brought fundamental changes. FERA was replaced by the more liberal Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999 (FEMA), which shifted the focus from regulation to management of foreign exchange[2]. More significantly, the enactment of PMLA in 2002 marked a watershed moment, transforming the ED from primarily a civil enforcement agency to a powerful criminal investigation body.

2005-Present: PMLA Implementation and Amendments The ED assumed responsibility for enforcing PMLA provisions from July 1, 2005[2]. Subsequent amendments in 2009, 2012, 2015, 2018, and 2019 progressively expanded the agency’s powers, broadened the definition of money laundering, and introduced stringent bail conditions.

Statutory Powers of the Enforcement Directorate and Jurisdiction Under PMLA

Comprehensive Investigation Powers

The Prevention of Money Laundering Act grants the ED extraordinary powers that set it apart from conventional law enforcement agencies. These powers include:

Search and Seizure (Section 17) ED officers can search premises and seize documents, records, and assets without prior judicial warrant if they have reason to believe that money laundering activities are being conducted. The Supreme Court has upheld these powers, noting that they contain adequate safeguards against misuse.

Power of Arrest (Section 19) Perhaps the most controversial provision, Section 19 empowers ED officers to arrest individuals based on “reason to believe” that they have committed money laundering offences. Unlike regular criminal law, no First Information Report (FIR) is required, and arrests can be made based on the internal Enforcement Case Information Report (ECIR).

Attachment and Confiscation of Property (Sections 5 and 8) The ED can provisionally attach properties suspected to be proceeds of crime for up to 180 days, which can be extended with court approval. This power operates independently of conviction in the underlying criminal case.

Summoning Powers (Section 50) The agency can summon any person to give evidence or produce documents during investigation. Non-compliance attracts penalties under Section 63 of PMLA and Section 174 of the Indian Penal Code.

The Relationship Between ED and CBI: Coordinated Financial Crime Investigation

A critical aspect of ED’s functioning is its relationship with other investigative agencies, particularly the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). Under the PMLA framework, money laundering is not a standalone offence but depends on the existence of a “scheduled offence” or “predicate offence”.

Mechanical Registration of ED Cases

In practice, ED cases are often registered mechanically following CBI complaints in financial crime matters. This coordination operates through the following mechanism:

- Primary Investigation by CBI: The CBI registers an FIR for offences like corruption, bank fraud, or economic offences listed in the PMLA Schedule.

- Automatic ED Involvement: Based on the CBI’s findings of criminal activity generating proceeds of crime, the ED registers an ECIR and initiates parallel investigation.

- Information Sharing: Both agencies share intelligence through formal and informal channels, with the Financial Intelligence Unit-India (FIU-IND) serving as a coordination mechanism.

This coordinated approach has led to criticism that ED cases are mechanically filed without independent evaluation of money laundering elements, effectively creating a parallel prosecution mechanism for the same underlying criminal activity.

Landmark Supreme Court Judgments on Powers of the Enforcement Directorate

Vijay Madanlal Choudhary v. Union of India (2022): The Watershed Judgment

The most significant judicial pronouncement on powers of the enforcement directorate came in the Vijay Madanlal Choudhary case, where a three-judge Supreme Court bench comprehensively upheld various PMLA provisions.

Key Holdings:

- Constitutional Validity: The Court upheld Sections 5, 8(4), 15, 17, 19, and 45 of PMLA as constitutionally valid.

- ED Not Police: The judgment established that ED officers are not police officers and hence not bound by Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) safeguards.

- ECIR Disclosure: The Court held that supplying ECIR to accused persons is not mandatory, as it is an “internal document” unlike an FIR.

- Broad Definition of Money Laundering: The Court adopted an expansive interpretation of money laundering, holding that “projecting” proceeds as untainted is not essential for the offence.

Nikesh Tarachand Shah v. Union of India (2017): The Bail Controversy

In a significant constitutional ruling, the Supreme Court struck down Section 45(1) of PMLA, which imposed stringent “twin conditions” for bail[33][34][35]. The Court held that these conditions violated Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution by creating arbitrary distinctions between different categories of offences.

Twin Conditions Struck Down:

- Opportunity to prosecution to oppose bail

- Court’s satisfaction that accused is prima facie not guilty and unlikely to commit offence while on bail[36][37]

However, Parliament subsequently reintroduced these conditions through the Finance Act 2018, leading to ongoing constitutional challenges.

Recent Judicial Interventions: Limiting ED Powers

Despite the broad validation in Vijay Madanlal Choudhary, recent Supreme Court decisions have begun placing limitations on powers of the enforcement directorate:

Tarsem Lal v. Directorate of Enforcement (2024) The Supreme Court held that ED cannot arrest an accused after a Special Court takes cognizance of a PMLA complaint. This represents a significant limitation on the agency’s arrest powers during the trial stage.

Territorial Jurisdiction and Summoning In Abhishek Banerjee v. Directorate of Enforcement, the Supreme Court clarified that ED’s summoning powers override territorial limitations under CrPC, but emphasized the need for reasonable nexus between the investigation and the place of summoning.

Bail Jurisprudence Under PMLA: The Evolving Landscape

The Stringent Bail Regime

Section 45 of PMLA creates one of the most stringent bail regimes in Indian criminal law. The provision establishes that no person accused of money laundering can be released on bail unless:

- Public Prosecutor Opposition: The prosecutor gets an opportunity to oppose bail

- Twin Test: If the prosecutor opposes, the court must be satisfied that there are reasonable grounds to believe the accused is not guilty and will not commit any offence while on bail

This regime places the burden of proof on the accused to establish their innocence—a reversal of the fundamental principle of presumption of innocence.

Recent Judicial Trends: Towards Liberalization

Despite the stringent statutory provisions, recent Supreme Court decisions indicate a trend towards liberalizing bail in PMLA cases:

Manish Sisodia Case (2024) The Supreme Court granted bail after 17 months of incarceration, emphasizing the right to speedy trial. The Court noted that with 69,000 pages of evidence and 493 witnesses, the trial had not even commenced.

Satyendar Jain Case (2024) A Delhi trial court granted bail after 18 months, with the judge observing that “trial is yet to begin, let alone conclude”. The court held that constitutional rights under Article 21 supersede statutory twin conditions when liberty is the core consideration.

- Chidambaram Precedent In the landmark P. Chidambaram cases, the Supreme Court granted bail in both CBI and ED matters, establishing important precedents for bail jurisprudence in economic offences.

Contemporary Bail Analysis

The evolving bail jurisprudence reveals several key principles:

- Right to Speedy Trial: Courts are increasingly emphasizing that prolonged incarceration without trial violates Article 21

- Proportionality: The nature of the offence and likely sentence are being weighed against the period of incarceration

- Constitutional Supremacy: Constitutional rights are being held to supersede statutory twin conditions in appropriate cases

Alleged Political Misuse: Supreme Court’s Growing Concerns

Recent Supreme Court Interventions

The Supreme Court has expressed increasing concern about the alleged misuse of Powers of the Enforcement Directorate for political purposes, particularly in 2025:

MUDA Case Criticism (July 2025) In the Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah’s wife case, the Supreme Court made scathing observations:

- “Why are you being used for political battles?”

- “Let political battles be fought amongst the electorate”

- The Court warned: “Please don’t ask us to open our mouth… otherwise we will be forced to make some harsh comments about the ED”

TASMAC Liquor Case Observations (May 2025) The Supreme Court stayed ED proceedings against Tamil Nadu State Marketing Corporation, observing:

- “ED is crossing all limits”

- “You are totally violating the federal structure of Constitution”

- The Court questioned how a criminal matter could be registered against a corporation rather than individuals

Summoning of Senior Advocates: Constitutional Concerns

In a shocking development that prompted Supreme Court intervention, the ED summoned Senior Advocates Arvind Datar and Pratap Venugopalfor legal opinions provided to their clients.

Supreme Court’s Response:

- “How can lawyers be summoned like this? This is privileged communication”

- The CJI expressed being “shocked” after reading about the summons

- The Court initiated suo motu proceedings and contemplated guidelines to prevent such overreach

The ED subsequently withdrew the summons and issued a circular requiring Director-level approval for any summons to advocates.

Pattern of Political Targeting: Statistical Analysis

While comprehensive statistics on political targeting are contested, several concerning patterns emerge:

Opposition Leaders Under Investigation: Recent high-profile ED cases have predominantly involved Opposition leaders and their associates:

- Arvind Kejriwal (Delhi Chief Minister) – Delhi Liquor Policy case

- Manish Sisodia (Former Deputy CM Delhi) – Same case, granted bail after 17 months

- Satyendar Jain (AAP leader) – Money laundering case, granted bail after 18 months

- Hemant Soren (Jharkhand Chief Minister) – Land scam case

- Various Congress leaders in multiple states

Judicial Recognition of Pattern: The Supreme Court has noted this pattern, with the CJI observing: “We are seeing it multiple times” regarding ED pursuing political matters.

Constitutional and Legal Challenges

Federal Structure Violations

The Supreme Court has increasingly highlighted ED’s violations of India’s federal structure:

State vs. Central Jurisdiction Conflicts:

- ED investigations in state subjects without clear central nexus

- Overriding state government objections in investigations

- Creating parallel prosecution mechanisms that bypass state law enforcement

Due Process Concerns

Several constitutional principles are under strain due to ED’s expansive powers:

Article 20(3) – Self-Incrimination: While the Supreme Court in Vijay Madanlal Choudhary held that ED officers are not police and hence Article 20(3) protections don’t apply at the summoning stage, this interpretation remains controversial.

Article 21 – Life and Personal Liberty: Courts are increasingly invoking Article 21 to counter PMLA’s stringent provisions, particularly regarding prolonged incarceration without trial.

Procedural Safeguards and Guidelines

The Supreme Court is moving towards establishing guidelines to regulate powers of the enforcement directorate:

Proposed Areas for Regulation:

- Lawyer-Client Privilege: Clear guidelines on when advocates can be summoned

- Arrest Procedures: Greater judicial oversight of arrest powers

- Territorial Jurisdiction: Clarification on when investigations can cross state boundaries

- Asset Attachment: Proportionality requirements for property attachment

International Comparisons and Best Practices

Global Anti-Money Laundering Frameworks

India’s PMLA framework, while comprehensive, raises concerns when compared with international best practices:

United Kingdom:

- Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 provides similar powers but with greater judicial oversight

- Independent oversight body (National Crime Agency) with parliamentary accountability

- Clearer separation between investigation and prosecution functions

United States:

- Bank Secrecy Act and related legislation provide extensive powers

- However, stronger constitutional protections and independent judiciary provide better safeguards

- Grand jury system ensures independent evaluation of evidence before prosecution

Canada:

- Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act balances enforcement with rights protection

- Independent review mechanisms and sunset clauses for extraordinary powers

- Greater integration with provincial law enforcement agencies

Recommendations for Reform

Based on international best practices and judicial concerns, several reforms merit consideration:

Institutional Reforms:

- Independent Oversight: Establishment of an independent oversight body for ED operations

- Parliamentary Accountability: Regular reporting to Parliament on ED activities and conviction rates

- Judicial Review: Mandatory judicial approval for arrests in politically sensitive cases

Procedural Reforms:

- Time-bound Investigations: Statutory timelines for completing investigations

- Proportionality Requirements: Matching the severity of enforcement action with the gravity of alleged offences

- Coordination Protocols: Clear guidelines for coordination between ED, CBI, and state agencies

Conclusion: Balancing Enforcement with Constitutional Values

The Enforcement Directorate represents a critical component of India’s financial crime enforcement architecture. Its establishment and evolution reflect genuine needs to combat increasingly sophisticated economic crimes, money laundering, and financial terrorism. The agency’s comprehensive powers under PMLA, FEMA, and FEOA are designed to address complex multi-jurisdictional financial crimes that traditional law enforcement agencies may struggle to investigate effectively.

However, the Supreme Court’s recent interventions highlight serious concerns about the agency’s functioning and its potential misuse for political purposes. The Court’s observations about ED being used for “political battles,” crossing “all limits,” and violating the “federal structure of Constitution” represent unprecedented judicial criticism of a central investigative agency.

Key Challenges Requiring Urgent Attention

- Political Neutrality: The predominant targeting of opposition leaders raises questions about the agency’s political neutrality and independence from executive influence.

- Constitutional Compliance: The tension between PMLA’s stringent provisions and constitutional rights requires careful judicial balancing to prevent the law from becoming a tool for harassment.

- Federal Balance: ED’s operations must respect India’s federal structure and not undermine state governments’ legitimate functions.

- Due Process: The agency’s extraordinary powers must be exercised within constitutional bounds, with adequate safeguards against misuse.

The Path Forward

The ED’s role in combating financial crimes remains vital, but its powers must be exercised with greater accountability and judicial oversight. The Supreme Court’s ongoing review of the Vijay Madanlal Choudhary judgment and contemplation of guidelines for ED operations represent important steps toward achieving this balance.

The challenge lies in preserving the agency’s effectiveness in investigating complex financial crimes while ensuring that its powers are not misused to undermine democratic institutions and constitutional values. This balance is essential not just for the rule of law, but for maintaining public confidence in India’s investigative agencies and judicial system.

As the legal and constitutional frameworks continue to evolve, the ED must demonstrate that it can operate as an independent, professional agency committed to combating financial crimes without fear or favor. Only through such commitment can the agency fulfill its constitutional mandate while respecting the democratic principles that underpin India’s legal system.

The ongoing judicial scrutiny and the prospect of clearer guidelines offer hope that India’s financial crime enforcement framework will emerge stronger, more accountable, and better aligned with constitutional values. The ultimate test will be whether these reforms translate into genuine changes in the agency’s functioning and public perception of its role in India’s democratic system.

[1] Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prevention_of_Money_Laundering_Act,_2002

[2] Powers of the ED Under Various Laws – Samisti Legal

https://samistilegal.in/powers-of-the-enforcement-directorate-under-various-laws-and-the-rights-of-the-accused-aggrieved-persons

[3] ED’s Arrest Powers in Money Laundering – B&B Legal

https://bnblegal.com/article/eds-arrest-powers-in-money-laundering

[4] Bail under PMLA – National Judicial Academy PDF

https://nja.gov.in/Concluded_Programmes/2019-20/P-1204_PPTs/6.PMLA%20BAIL.pdf

[5] Review of the SC’s Vijay Madanlal Judgment – SC Observer

https://www.scobserver.in/cases/karti-p-chidambaram-v-enforcement-directoratereview-of-the-scs-vijay-madanlal-judgement

[6] Nikesh Tarachand Shah v. Union of India – In House Lawyer

https://www.inhouselawyer.co.uk/legal-briefing/nikesh-tarachand-shah-v-union-of-india-constitutionality-of-the-pre-bail-conditions-provided-in-the-prevention-of-the-money-laundering-act-2002

[7] A Narrow Check on ED’s Wide Powers – SC Observer

https://www.scobserver.in/journal/a-narrow-check-on-the-eds-wide-powers-pmla-supreme-court

[8] SC Orders Judicial Review of ED Arrests – Metalegal (Kejriwal Case)

https://www.metalegal.in/post/arvind-kejriwal-v-ed-supreme-court-mandates-judicial-review-of-ed-arrests-under-pmla

[9] ED’s Power to Arrest After Cognisance – Tarsem Lal v. ED – SC Observer

https://www.scobserver.in/cases/enforcement-directorates-power-to-arrest-under-pmla-after-special-courts-cognisance-tarsem-lal-v-directorate-of-enforcement

[10] In Prem Prakash, SC Moves Away from Vijay Madanlal – SC Observer

https://www.scobserver.in/journal/in-prem-prakash-the-supreme-court-takes-another-step-away-from-vijay-madanlal-bail

[11] Accused Entitled to Records Seized by ED – SC Observer (Sarla Gupta Case)

https://www.scobserver.in/supreme-court-observer-law-reports-scolr/pmla-accused-entitled-to-records-seized-by-ed-including-list-of-unrelied-documents-sarla-gupta-v-directorate-of-enforcement

[12] SC Slams Political Weaponization of ED – Hans India

https://www.thehansindia.com/news/national/supreme-court-slams-enforcement-directorate-for-political-weaponization-in-legal-proceedings-989717

Supreme Court on Section 7: ‘May’ Clause Not a Valid Arbitration Agreement in BGM v. Eastern Coalfields

The Supreme Court’s Landmark Ruling

The Indian Supreme Court’s recent judgment in BGM and M-RPL-JMCT (JV) vs Eastern Coalfields Limited has provided much-needed clarity on what constitutes a valid arbitration agreement under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996[1]. The Court’s unequivocal ruling that a contract clause stating disputes “may be” referred to arbitration does not amount to a binding arbitration agreement has significant implications for commercial contracting and dispute resolution practice in India.

Understanding Section 7 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

Section 7 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, forms the cornerstone of arbitration law in India. The section defines an “arbitration agreement” as:

“an agreement by the parties to submit to arbitration all or certain disputes which have arisen or which may arise between them in respect of a defined legal relationship, whether contractual or not”[2][3]

The statutory requirements under Section 7 mandate that:

- An arbitration agreement must be in writing

- It may be in the form of an arbitration clause in a contract or a separate agreement

- It must demonstrate clear intention to refer disputes to arbitration

The Critical Distinction: Enabling Clauses vs. Binding Agreements

What the Supreme Court Said

In the BGM case, the Supreme Court examined Clause 13 of a contract between Eastern Coalfields Limited and a joint venture. The relevant portion of the clause read:

“In case of parties other than Govt. Agencies, the redressal of the dispute may be sought through Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 as amended by Amendment Act of 2015″[1]

The Court observed that this phraseology created merely an enabling clause rather than a binding arbitration agreement. Justice PS Narasimha and Justice Manoj Misra held:

“It is just an enabling clause whereunder, if parties agree, they could resolve their dispute(s) through arbitration. The phraseology of clause 13 is not indicative of a binding agreement that any of the parties on its own could seek redressal of inter se dispute(s) through arbitration”[1][4][5]

Legal Principles Established

The Supreme Court established several crucial principles:

- Language Matters: The use of “may be sought” implies no subsisting agreement between parties to arbitrate[1]

- Mandatory vs. Permissive: An enabling clause requiring future consent differs fundamentally from a binding arbitration agreement[6]

- Intention Test: The clause must demonstrate unequivocal intention to refer disputes to arbitration without requiring further consent[7][8]

Global Perspective on “May” vs. “Shall” in Arbitration Clauses

The International Approach

Courts worldwide have grappled with the interpretation of permissive language in arbitration clauses. The distinction between mandatory and permissive arbitration clauses has evolved differently across jurisdictions:

United States: Most American courts hold that language providing a party “may” submit disputes to arbitration creates mandatory arbitration once invoked[9][10]. The rationale is that without this interpretation, arbitration clauses would become meaningless since parties could always voluntarily arbitrate[11].

United Kingdom: The Privy Council in Anzen Ltd v. Hermes One Ltd held that “may” language creates an option to arbitrate, exercisable by either party, rather than a binding obligation[12][13]. English courts require “shall” or “must” for binding arbitration agreements[12].

India: The Supreme Court’s approach aligns more closely with the English position, requiring clear mandatory language for valid arbitration agreements.

Essential Elements of a Valid Arbitration Agreement

Based on judicial precedents and statutory requirements, a valid arbitration agreement must contain[7][8]:

1. Clear and Unambiguous Intention to Arbitrate

The agreement must demonstrate an unequivocal intention of parties to refer disputes to arbitration without leaving the decision to future consent or negotiation.

2. Obligation to Submit Disputes

The Supreme Court in Jagdish Chander v. Ramesh Chander held that an arbitration agreement cannot require further agreement for reference to arbitration[7][8].

3. Reference to Neutral Tribunal

The agreement should provide for resolution by an impartial arbitrator or arbitral tribunal.

4. Defined Scope

The agreement must clearly specify which disputes are covered by the arbitration clause.

Drafting Best Practices: Avoiding Pathological Clauses

Recommended Language

For Mandatory Arbitration:

“Any dispute, controversy or claim arising out of or relating to this contract shall be settled by arbitration in accordance with [applicable rules]”

Avoid:

“Disputes may be referred to arbitration if parties agree”

“The parties can resolve disputes through arbitration”

Key Drafting Principles

- Use Mandatory Language: Employ “shall,” “will,” or “must” rather than “may,” “can,” or “might”[12][14][15]

- Be Specific: Clearly define the scope of disputes covered[15]

- Avoid Ambiguity: Ensure the clause leaves no room for interpretation regarding the parties’ obligation to arbitrate[15]

- Include Essential Details: Specify the seat of arbitration, applicable rules, and method of appointing arbitrators[14][15]

Section 11 and Judicial Intervention

Section 11 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act empowers courts to appoint arbitrators when parties cannot agree. However, the 2015 Amendment restricted judicial intervention through Section 11(6A), which limits courts to examining only the “existence” of an arbitration agreement[16][17].

The Supreme Court in BGM confirmed that courts must confine their examination to whether a valid arbitration agreement exists, without delving into the merits of the dispute[1][5].

Recent Judicial Trends

The Pro-Arbitration Stance

Recent Supreme Court decisions demonstrate a pro-arbitration approach while maintaining strict standards for what constitutes a valid arbitration agreement:

- Tarun Dhameja v. Sunil Dhameja: The Court held that arbitration cannot be “optional” requiring mutual consent of all parties[18][19][20]

- N.N. Global Mercantile v. Indo Unique Flame: A seven-judge Constitution Bench held that unstamped arbitration agreements remain valid[17]

Evolution of Jurisprudence

Indian arbitration law has evolved significantly since the BALCO case (2012), which restricted judicial intervention in international arbitrations[21]. The 2015 amendments further strengthened this approach by limiting court interference[16].

Practical Implications for Commercial Practice

For Businesses

- Review Existing Contracts: Companies should audit their dispute resolution clauses to ensure they contain mandatory arbitration language

- Standardize Language: Adopt model arbitration clauses from recognized institutions

- Legal Consultation: Engage experienced counsel when drafting arbitration agreements

For Legal Practitioners

- Careful Drafting: Pay close attention to the language used in arbitration clauses

- Client Education: Inform clients about the difference between enabling clauses and binding arbitration agreements

- Precedent Awareness: Stay updated with evolving jurisprudence on arbitration agreements

Comparative Analysis: Different Types of Arbitration Clauses

| Type | Language | Effect | Enforceability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mandatory | “shall,” “must,” “will” | Binding obligation to arbitrate | Fully enforceable[12][14] |

| Permissive/Optional | “may,” “can,” “might” | Creates option, not obligation | Limited enforceability[9][22] |

| Enabling | “may be sought,” “can be resolved” | Requires further consent | Not enforceable as standalone agreement[1][6] |

The Doctrine of Separability and Arbitration Agreements

The doctrine of separability, codified in Section 16(1) of the Arbitration Act, treats arbitration clauses as separate agreements independent of the main contract[23]. This principle ensures that even if the main contract is void, the arbitration agreement can survive, provided it meets the requirements of Section 7[24][23].

Future Outlook and Legislative Developments

The establishment of the Arbitration Council of India under Part IA of the Act (Sections 43A-43M) represents a significant step toward institutionalizing arbitration in India[2]. The Council’s role in grading arbitral institutions and accrediting arbitrators will likely influence how arbitration agreements are interpreted and enforced.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s decision in BGM v. Eastern Coalfields Limited provides essential clarity on the distinction between binding arbitration agreements and mere enabling clauses. The ruling reinforces that intention matters in arbitration law – parties must demonstrate clear, unambiguous commitment to resolve disputes through arbitration.

For the legal community and business practitioners, this judgment serves as a crucial reminder that words matter in contract drafting. The difference between “may” and “shall” can determine whether a dispute ends up in arbitration or faces prolonged litigation over the validity of the arbitration clause itself.

As India continues to strengthen its position as an arbitration-friendly jurisdiction, understanding these fundamental principles becomes increasingly important for all stakeholders in the dispute resolution ecosystem. The key takeaway is clear: if parties genuinely intend to arbitrate their disputes, their agreement must reflect that intention in mandatory, unambiguous language that creates binding obligations rather than mere possibilities.

Citations:

[1] Contract clause saying disputes ‘may be’ referred to arbitration is not an arbitration agreement: Supreme Court https://www.barandbench.com/news/litigation/contract-clause-saying-disputes-may-be-referred-to-arbitration-is-not-an-arbitration-agreement-supreme-court

[2] Arbitration agreement – India Code: Section Details https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_3_46_00004_199626_1517807323919&orderno=7

[3] Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 – India Code https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1978/3/a1996-26.pdf

[4] COMMERCIAL ARBITRATION ACT 2011 – SECT 11 Appointment of arbitrators (cf Model Law Art 11) http://www8.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/legis/vic/consol_act/caa2011219/s11.html

[5] V101- Arbitration Law -1 || Appointment of Arbitrators in India by High Courts & Supreme Court https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t322oag6JKU

[6] October 19 2023 https://www.cliffordchance.com/content/dam/cliffordchance/briefings/2023/10/supreme-court-provides-guidance-on-matters-falling-within-scope-of-an-arbitration-agreement.pdf

[7] Arbitration Agreements Outside The Scope Of A Signed Document: An Unconventional Mechanism To Submit https://www.mondaq.com/india/trials-amp-appeals-amp-compensation/1059004/arbitration-agreements-outside-the-scope-of-a-signed-document-an-unconventional-mechanism-to-submit-a-dispute-to-arbitration

[8] Arbitration in 2024: Landmark Rulings and Key Takeaways https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/01/08/arbitration-2024-landmark-cases/

[9] Examining the Validity of Asymmetrical and Optional Arbitration … https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2022/02/15/examining-the-validity-of-asymmetrical-and-optional-arbitration-clauses/

[10] Arbitration Clauses in Construction Agreements: Mandatory or … https://www.airdberlis.com/insights/publications/publication/arbitration-clauses-in-construction-agreements-mandatory-or-permissive

[11] [PDF] Guide to Drafting ADR Clauses https://sadr.org/assets/uploads/download_file/Guide_To_Drafting_ADR_Clauses_EN.pdf

[12] Drafting an Arbitration Agreement – CMS LAW-NOW https://cms-lawnow.com/en/ealerts/1999/04/drafting-an-arbitration-agreement

[13] [PPT] Drafting Arbitration Clause – University of Delhi https://lc2.du.ac.in/DATA/VI%20Tth%20Semester%20(ADR)%20PPT%20Drafting%20Arbitration%20Clause%20by%20Dr.%20Ashish%20Kumar.pptx

[14] INDIAN SUPREME COURT CLARIFIES APPLICABILITY OF THE … https://www.hsfkramer.com/notes/arbitration/2023-12/indian-supreme-court-clarifies-applicability-of-the-group-of-companies-doctrine-in-cox-and-kings-ltd-v-sap-india-private-ltd

[15] [PDF] ARBITRATION IN INDIA – Lakshmikumaran & Sridharan https://www.lakshmisri.com/Media/Uploads/Documents/L&S_Arbitration_Booklet_Oct2014.pdf

[16] Opening Pandora’s Box: Unpacking the Principles Relating to the Law Governing the Arbitration Agreement Across Various Jurisdictions | Withers https://www.withersworldwide.com/en-gb/insight/read/unpacking-principles-relating-to-law-governing-arbitration-agreement-across-various-jurisdictions

[17] Supreme Court Of India Clarifies ‘What Is Arbitrable’ Under Indian Law And Provides Guidance To Forums In Addressing The Question https://www.livelaw.in/law-firms/articles/supreme-court-clarifies-arbitrable-indian-law-168218

[18] Differential and More Favourable Treatment Reciprocity and Fuller … https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/enabling1979_e.htm

[19] When An Arbitration Clause Sounds Permissive But Is Not — Does “May” Really Mean “Must”? https://natlawreview.com/article/when-arbitration-clause-sounds-permissive-not-does-may-really-mean-must

[20] International Commercial https://www.skadden.com/-/media/files/publications/2014/04/april2014_draftingnotes.pdf

[21] The law of the arbitration agreement – which law applies and why does it matter? https://www.herbertsmithfreehills.com/notes/arbitration/2012-05/the-law-of-the-arbitration-agreement-which-law-applies-and-why-does-it-matter

[22] Jurisdiction: permissive arbitration clause https://www.arbitrationlawmonthly.com/arbitration/jurisdiction/jurisdiction-permissive-arbitration-clause–1.htm

[23] [PDF] REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL … https://api.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2021/20788/20788_2021_1_1501_61506_Judgement_30-Apr-2025.pdf

[24] Arbitration Agreement and Doctrine of Separability – LawTeacher.net https://www.lawteacher.net/free-law-essays/contract-law/arbitration-agreement-and-doctrine-of-separability-contract-law-essay.php

Gujarat High Court’s Jurisdiction to Issue Writs Against DRI Mumbai: A Comprehensive Legal Analysis Based on the Swati Menthol Judgment

Understanding Territorial Jurisdiction and Cross-Border Enforcement in Customs Matters

The landmark judgment in Swati Menthol & Allied Chemicals Ltd. v. Joint Director, DRI has established crucial precedents regarding the Gujarat High Court’s authority to issue writs against DRI Mumbai for actions taken outside its territorial jurisdiction. This detailed analysis explores the legal foundations, procedural requirements, and practical implications of such cross-jurisdictional enforcement powers

The Core Issue: When Can Gujarat High Court Exercise Jurisdiction Over DRI Mumbai?

The fundamental question addressed in paragraphs 6-8 of the Swati Menthol judgment centers on whether the Gujarat High Court has territorial jurisdiction to entertain writs petition against DRI officers stationed in Mumbai when their actions affect businesses operating in Gujarat[1].

Key Holdings from Paragraphs 6-8

The Gujarat High Court’s analysis in paragraphs 6-8 specifically addressed the principal grievance that DRI authorities stationed at Ahmedabad (outside the place of import at Mumbai) had taken action regarding goods imported at Nhava Sheva, Mumbai[1]. The Court examined whether such cross-jurisdictional actions could be challenged through Writs Against DRI Mumbai before the Gujarat High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution.

Critical Legal Framework: The Court established that a High Court can exercise writ jurisdiction if any part of the cause of action arises within its territorial jurisdiction, even when the principal customs action occurs outside its boundaries[1][2]. This interpretation significantly broadens the scope of remedial jurisdiction available to affected parties.

Constitutional Provisions Enabling Cross-Border Writ Jurisdiction

Article 226(2): The Foundation of Territorial Expansion

Article 226(2) of the Constitution provides the legal basis for the Gujarat High Court’s expanded jurisdiction[2][3]. The provision states:

“The power conferred by clause (1) to issue directions, orders or writs to any Government, authority or person may also be exercised by any High Court exercising jurisdiction in relation to the territories within which the cause of action, wholly or in part, arises for the exercise of such power, notwithstanding that the seat of such Government or authority or the residence of such person is not within those territories”[2].

Cause of Action Doctrine vs. Situs Doctrine

The Court’s decision reflects the cause of action doctrine, which allows High Courts to exercise jurisdiction based on where the cause of action arises, rather than being limited by the situs doctrine that restricts jurisdiction to where the authority is physically located[4][5].

Practical Application: In customs matters, this means that if a Gujarat-based company faces adverse action from DRI Mumbai, the cause of action partly arises in Gujarat due to:

- The company’s business operations in Gujarat[6]

- Economic impact on Gujarat-based activities[6]

- Documentary and payment transactions occurring in Gujarat[6]

The Proper Officer Concept and DRI’s Authority

Section 2(34) of the Customs Act: Defining Proper Officer

A crucial aspect of the Swati Menthol case involved determining whether DRI officers qualify as “proper officers” under Section 2(34) of the Customs Act, 1962[1][7][8]. The provision defines proper officer as:

“The officer of customs who is assigned those functions by the Board or the Commissioner of Customs”[7][8].

Notifications Empowering DRI Officers

The Court examined several key notifications that established DRI’s authority:

- Notification dated 6-7-2011: This critical notification assigned functions under Sections 17 and 28 of the Customs Act to DRI officers, specifically designating them as “proper officers” for issuing show cause notices[1].

- Notification dated 2-5-2012: While this subsequent notification did not explicitly assign adjudication functions to DRI officers, the Court held that it did not rescind the earlier notification, allowing both to operate simultaneously[1].

Jurisdictional Limitations and Safeguards

The Court noted an important safeguard: DRI officers can issue show cause notices but cannot adjudicate them[1]. The clarification issued by C.B.E. & C. on 23-9-2011 specified that DRI officers “would continue the practice of not adjudicating the show cause notice issued under Section 28 of the Act”[1].

Maintainability Conditions for Writ Petitions

Five Exceptional Circumstances

For a writ petition to be maintainable against government authorities, particularly in cross-border enforcement scenarios, courts have established five exceptional circumstances[7][8]:

- Violation of Fundamental Rights

- Violation of Principles of Natural Justice

- Orders passed wholly without jurisdiction

- Challenge to the vires of legislation

- Pure questions of law devoid of disputed facts[7][8]

Distinction Between Maintainability and Entertainability

Recent jurisprudence has clarified that *maintainability and entertainability are distinct concepts*[9][10]. A writ petition may be legally maintainable but still not entertained by the Court due to factors such as:

- Availability of alternative remedies

- Application of the doctrine of forum conveniens

- Discretionary considerations under Article 226[9][10]

Practical Implications for Legal Practice

Strategic Considerations for Practitioners

When advising clients on challenging DRI Mumbai actions before Gujarat High Court, practitioners should consider:

Establishing Cause of Action: Clearly demonstrate how the impugned action creates consequences within Gujarat’s territorial jurisdiction[5][2]. This may include:

- Impact on business operations in Gujarat

- Financial consequences affecting Gujarat-based assets

- Disruption to Gujarat-based supply chains or contractual obligations

Jurisdictional Challenges: Be prepared to address potential objections regarding territorial jurisdiction by citing the expanded interpretation under Article 226(2)[2][3].

Alternative Remedies: Address the availability and efficacy of alternative remedies, as courts may decline to entertain writ petitions where adequate alternative forums exist[9][10].

Documentation and Evidence Requirements

For successful writ petitions under these circumstances, ensure comprehensive documentation of:

- Business registration and operations in Gujarat

- Financial impact statements showing Gujarat-specific consequences

- Correspondence and transactions occurring within Gujarat

- Timeline demonstrating the sequence of events affecting Gujarat interests

Comparative Analysis with Other High Courts

Divergent Approaches Across Jurisdictions

Different High Courts have adopted varying approaches to cross-border enforcement issues[4]. While the Gujarat High Court in Swati Menthol adopted a liberal interpretation favoring expanded territorial jurisdiction, other High Courts have been more restrictive[11][12].

Recent Trends: There’s been growing recognition that strict territorial limitations may unduly restrict access to justice in an interconnected economy[4][16]. This has led to more flexible interpretations of Article 226(2) across various High Courts.

Recent Developments and Legislative Changes

Impact of Customs (Amendment and Validation) Act, 2011

The insertion of sub-section (11) to Section 28 of the Customs Act through the 2011 amendment was specifically designed to address jurisdictional challenges following the Supreme Court’s decision in Commissioner of Customs v. Sayed Ali[1][13].

Retrospective Validation: The amendment retrospectively validated notices issued by customs officers who were appointed before July 6, 2011, thereby addressing potential jurisdictional defects[1][13].

Current Practice and Procedure

In contemporary practice, the following procedure is generally followed:

- Notice Issuance: DRI officers can issue show cause notices under Section 28[1]

- Adjudication Transfer: Adjudication proceedings are transferred to competent customs officers at the relevant port[1]

- Writ Remedies: Affected parties can approach High Courts based on cause of action principles[1][2]

Conclusion and Future Outlook

The Swati Menthol judgment represents a significant milestone in expanding territorial jurisdiction for writ remedies in customs matters. By establishing that Gujarat High Court can issue writs against DRI Mumbai actions when part of the cause of action arises within Gujarat, the judgment enhances access to justice for businesses operating across state boundaries.

Key Takeaways

- Expanded Jurisdiction: Article 226(2) allows High Courts to exercise writ jurisdiction based on partial cause of action within their territory

- DRI Authority: DRI officers are proper officers for issuing notices but not for adjudication

- Strategic Litigation: Businesses can strategically choose forums based on where consequences of government action are felt

- Procedural Safeguards: Multiple layers of review exist to prevent abuse of cross-border jurisdiction

Looking Forward

As India’s economy becomes increasingly integrated, courts are likely to adopt more flexible approaches to territorial jurisdiction. The Swati Menthol precedent provides a strong foundation for challenging administrative actions such as Writs Against DRI Mumbai across state boundaries while maintaining appropriate checks and balances.

Legal practitioners should stay informed about evolving jurisprudence in this area, as cross-border enforcement mechanisms continue to develop in response to modern commercial realities. The balance between territorial limitations and access to justice will remain a key consideration in future developments of administrative law practice.

This comprehensive framework established by the Gujarat High Court ensures that businesses are not denied effective remedies merely due to the administrative convenience of government authorities operating across state boundaries, while maintaining the integrity of jurisdictional principles that underpin India’s federal judicial structure.

Citations:

[1] Swati Menthol & Allied Chem. Ltd. v. Jt. Dir., DRI | Gujarat High Court https://www.casemine.com/judgement/in/5ba0bdc560d03e57b21bbc57

[2] Exercise Of Territorial Jurisdiction Of High Court Under Article 226 (2) Of Constitution Can Only Be Invoked Where the Cause Of Action Arises | Legal Service India – Law Articles – Legal Resources https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-2259-exercise-of-territorial-jurisdiction-of-high-court-under-article-226-2-of-constitution-can-only-be.html

[3] A Legal Marketer’s SEO Cheat Sheet for Improving Your Writing and Rankings https://www.attorneyatwork.com/a-legal-marketers-seo-cheat-sheet-for-improving-your-writing-and-rankings/

[4] High Courts’ Territorial Jurisdiction under Articles 226 and 227 Over … https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/04/10/high-courts-territorial-jurisdiction-under-articles-226-and-227-over-orders-passed-by-appellate-tribunals-a-need-for-course-correction/

[5] [PDF] 1 WP-19795-2024 The present petition, under Article 226/227 of the … https://mphc.gov.in/upload/gwalior/MPHCGWL/2024/WP/19795/WP_19795_2024_FinalOrder_24-07-2024.pdf

[6] territorial jurisdiction doctypes: judgments https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=territorial+jurisdiction+doctypes%3Ajudgments

[7] [PDF] JSA Prism Dispute Resolution https://www.jsalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/JSA-Prism-Dispute-Resolution-February-2023-Godrej.Final0768.pdf

[8] [PDF] Cross-border Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judicial … https://assets.hcch.net/docs/76e4926e-962d-4621-97b5-c3e98d20eb53.pdf

[9] Resolving cross-border commercial disputes: jurisdiction and enforcement considerations https://www.cripps.co.uk/thinking/resolving-cross-border-commercial-disputes-jurisdiction-and-enforcement-considerations/?pdf=9919

[10] Cross-Border Litigation and Comity of Courts – Conflict of Laws .net https://conflictoflaws.net/2024/cross-border-litigation-and-comity-of-courts-a-landmark-judgment-from-the-delhi-high-court/

[11] High Court Rejects Writ Petition over Territorial Jurisdiction Limits in … https://www.taxtmi.com/tmi_blog_details?id=818052

[12] High Court Rejects Writ Petition over Territorial Jurisdiction Limits in … https://www.taxmanagementindia.com/web/tmi_blog_details.asp?id=818052

[13] http://JUDIS.NIC.IN https://main.sci.gov.in/jonew/judis/26138.pdf