Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

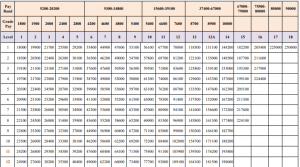

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

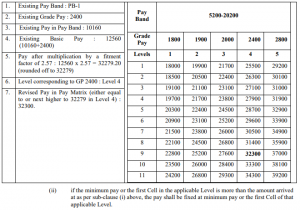

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

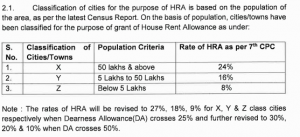

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

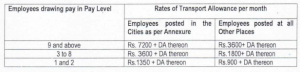

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

India’s Legal Reforms 2025: Extended Producer Responsibility and Live-Streaming Court proceedings

Introduction

India’s legal landscape has witnessed significant transformations in 2025, particularly in environmental law and judicial proceedings. The evolution of Extended Producer Responsibility and Live-Streaming Court frameworks, along with the growing adoption of digital judicial practices, represent pivotal shifts in how the Indian legal system addresses contemporary challenges. These developments reflect the nation’s commitment to environmental sustainability and judicial accessibility while maintaining the integrity of legal processes.

The convergence of environmental regulation and digital judicial processes demonstrates India’s adaptive approach to modern governance challenges. While Extended Producer Responsibility mechanisms continue to evolve under existing environmental protection frameworks, the integration of technology in court proceedings has become increasingly institutionalized across multiple High Courts and the Supreme Court of India.

Extended Producer Responsibility: Legal Framework and Recent Developments

Constitutional and Legislative Foundation

Extended Producer Responsibility operates under the umbrella of India’s constitutional commitment to environmental protection as enshrined in Article 48A and Article 51A(g) of the Constitution. The legislative framework primarily derives its authority from the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, which provides the Central Government with comprehensive powers to regulate environmental matters [1].

The Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, under Section 3, empowers the Central Government to take measures necessary for protecting and improving the quality of the environment. Section 6 specifically authorizes the government to make rules for regulating the discharge of environmental pollutants, which forms the legal basis for Extended Producer Responsibility regulations.

Evolution of EPR Regulations in 2025

The year 2025 has marked significant developments in the Extended Producer Responsibility framework, particularly through amendments to the Hazardous Waste Management Rules. The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change introduced comprehensive modifications to ensure safe handling, generation, processing, treatment, packaging, storage, transportation, and disposal of hazardous waste [2].

These regulatory changes emphasize the principle that producers must assume responsibility for the entire lifecycle of their products, particularly post-consumer waste management. The framework requires manufacturers, importers, and brand owners to establish comprehensive waste management systems that comply with Central Pollution Control Board regulations.

Implementation Mechanisms and Compliance Structure

The Extended Producer Responsibility system operates through a structured compliance framework that requires producers to register with appropriate regulatory authorities and submit detailed waste management plans. The Central Pollution Control Board has established centralized portals for different categories of waste, including plastic packaging, to streamline the registration and monitoring process [3].

Under the current regulatory structure, producers must demonstrate their capacity to handle projected waste generation through approved collection and recycling networks. The system mandates annual reporting of waste collection and recycling activities, with regular audits to ensure compliance with established targets and standards.

Legal Implications and Penalty Structure

Non-compliance with Extended Producer Responsibility requirements attracts penalties under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986. Section 15 of the Act prescribes imprisonment for a term which may extend to five years, or a fine which may extend to one lakh rupees, or both [4]. For continuing violations, additional fines may be imposed for each day the violation continues.

The penalty structure reflects the seriousness with which environmental violations are treated under Indian law. Foreign companies importing products into India are equally subject to these requirements, establishing the extraterritorial application of EPR obligations for businesses operating in the Indian market.

Live-Streaming and Mobile Court Hearings: Judicial Innovation

Legal Authority and Regulatory Framework

The implementation of live-streaming court proceedings finds its legal foundation in the inherent powers of the judiciary to regulate its own procedures, as recognized under Article 145 of the Constitution for the Supreme Court and corresponding provisions for High Courts. The Supreme Court’s decision to introduce live-streaming was formalized through specific guidelines that balance transparency with judicial dignity.

The Department of Justice, Ministry of Law and Justice, has provided oversight for the implementation of live-streaming across multiple High Courts. As of 2025, live-streaming has been operationalized in High Courts of Gujarat, Orissa, Karnataka, Jharkhand, Patna, Gauhati, Uttarakhand, Calcutta, Madhya Pradesh, Meghalaya, and Telangana, along with Constitutional Bench proceedings of the Supreme Court [5].

Technical Standards and Implementation Guidelines

The e-Committee of the Supreme Court of India has developed comprehensive Model Rules for Live-Streaming and Recording of Court Proceedings, which establish technical standards and procedural requirements for implementing digital broadcasting of judicial proceedings [6]. These rules address critical aspects including video quality standards, audio clarity requirements, and security protocols to prevent unauthorized access or manipulation.

The technical infrastructure for live-streaming requires robust internet connectivity, professional-grade audio-visual equipment, and secure streaming platforms that can handle multiple concurrent viewers while maintaining the sanctity of court proceedings. The National Informatics Centre provides technical support and hosting services for these digital initiatives.

Privacy and Confidentiality Considerations

The implementation of live-streaming court proceedings necessitates careful consideration of privacy rights and confidentiality requirements. Certain categories of cases, including those involving minors, matrimonial disputes, and sensitive commercial matters, are typically excluded from live-streaming to protect the interests of the parties involved.

The judicial system has established protocols to ensure that sensitive information disclosed during proceedings is not inappropriately broadcast or recorded. These measures include the ability to temporarily suspend live-streaming when confidential matters are being discussed and the implementation of delayed broadcasting for certain types of proceedings.

Impact on Legal Practice and Access to Justice

Live-streaming of court proceedings has significantly enhanced public access to judicial processes, allowing legal practitioners, academic institutions, and the general public to observe court proceedings in real-time. This development aligns with the constitutional principle of open justice while utilizing technology to overcome geographical barriers.

The availability of live-streamed proceedings has particular significance for legal education, enabling law students and practitioners to observe high-quality judicial discourse and procedural practices. Additionally, it facilitates better preparation for legal professionals who can observe similar matters being argued before different benches.

Convergence of Environmental Law and Digital Proceedings

Case Law Developments Through Digital Platforms

The combination of evolving environmental law and digital court proceedings has created new opportunities for developing environmental jurisprudence. Several significant environmental cases have been live-streamed, allowing for broader public engagement with environmental legal issues and increasing transparency in judicial decision-making processes.

The Supreme Court’s approach to environmental matters, as demonstrated in cases such as M.C. Mehta v. Union of India and subsequent environmental jurisprudence, continues to evolve through digital platforms that make these proceedings accessible to environmental lawyers, activists, and researchers across the country [7].

Regulatory Enforcement Through Digital Monitoring

The integration of digital technologies in both environmental regulation and judicial proceedings has enhanced the effectiveness of regulatory enforcement. Environmental compliance monitoring can now be more effectively adjudicated through courts that utilize digital evidence presentation and remote hearing capabilities.

The Central Pollution Control Board and State Pollution Control Boards can present real-time environmental data and monitoring reports through digital court systems, enabling more informed judicial decision-making in environmental matters. This technological integration has improved the speed and accuracy of environmental litigation.

Challenges and Future Considerations of EPR and Live-Streaming Courts in India

Technical Infrastructure Requirements

The successful implementation of both Extended Producer Responsibility systems and live-streaming court proceedings requires substantial technical infrastructure investments. Rural and remote areas may face challenges in accessing high-speed internet connections necessary for participating in digital court proceedings or complying with online EPR reporting requirements.

The digital divide presents ongoing challenges for ensuring equitable access to both environmental compliance systems and judicial proceedings. Addressing these technological disparities remains crucial for the effective implementation of these legal innovations.

Regulatory Harmonization Needs

The rapid evolution of both environmental regulations and digital judicial procedures requires careful coordination to ensure regulatory coherence. Different states may implement varying standards for EPR compliance and digital court proceedings, potentially creating compliance challenges for businesses and legal practitioners operating across state boundaries.

Harmonizing technical standards, procedural requirements, and reporting mechanisms across different jurisdictions will be essential for maintaining the effectiveness and accessibility of these legal innovations. The development of uniform national standards while respecting state autonomy presents an ongoing regulatory challenge.

Privacy and Security Considerations

Both Extended Producer Responsibility and live-streaming court proceedings involve the collection and dissemination of potentially sensitive information. Ensuring robust cybersecurity measures and privacy protections while maintaining transparency and accessibility requirements creates complex technical and legal challenges.

The protection of commercial sensitive information in EPR reporting systems and the safeguarding of personal information in court proceedings require sophisticated technical solutions and comprehensive legal frameworks that balance competing interests.

International Perspectives and Comparative Analysis

Global Best Practices in Extended Producer Responsibility Implementation

India’s Extended Producer Responsibility framework draws upon international best practices while adapting to local conditions and requirements [8]. European Union directives on Extended Producer Responsibility have influenced the development of Indian regulations, particularly in areas such as packaging waste management and electronic waste handling.

The implementation of EPR systems in developed countries provides valuable insights into effective regulatory structures, monitoring mechanisms, and compliance frameworks that can inform the continued evolution of India’s environmental regulations.

Digital Court Proceedings: International Trends

The adoption of live-streaming court proceedings in India aligns with global trends toward greater judicial transparency and accessibility. Several countries have implemented similar systems, providing comparative data on the effectiveness and challenges associated with digital judicial proceedings [9].

International experience suggests that successful implementation of digital court proceedings requires careful attention to technical standards, procedural safeguards, and ongoing training for judicial officers and legal practitioners. These lessons inform India’s continued development of digital judicial infrastructure.

Economic and Social Impact Analysis

Economic Implications of EPR Implementation

The Extended Producer Responsibility framework creates significant economic implications for businesses operating in India. Companies must invest in waste management infrastructure, establish recycling networks, and implement comprehensive tracking systems to demonstrate compliance with regulatory requirements.

While these requirements impose additional costs on producers, they also create new economic opportunities in the recycling and waste management sectors. The development of EPR compliance services has emerged as a significant business sector, providing specialized services to help companies meet their regulatory obligations.

Social Benefits of Digital Court Access

Live-streaming court proceedings democratizes access to judicial processes, allowing citizens who cannot physically attend court sessions to observe proceedings and understand legal processes. This enhanced accessibility particularly benefits rural communities, students, and individuals with mobility limitations.

The educational value of accessible court proceedings cannot be understated, as it provides opportunities for civic education and legal awareness that contribute to a more informed citizenry. This transparency also enhances public confidence in the judicial system by making court proceedings more visible and accountable.

Conclusion and Future Outlook

The developments in Extended Producer Responsibility regulations and live-streaming court proceedings represent significant advances in India’s legal and regulatory framework. These innovations demonstrate the country’s commitment to environmental protection and judicial accessibility while embracing technological solutions to contemporary challenges.

The continued evolution of these systems will require ongoing attention to technical infrastructure development, regulatory harmonization, and the balance between transparency and privacy. Success in these areas will depend upon sustained collaboration between government agencies, the judiciary, the legal profession, and technology providers.

As India continues to develop as a major economy with growing environmental consciousness and technological capabilities, these legal innovations position the country as a leader in adaptive governance. The integration of environmental responsibility and digital judicial processes provides a foundation for addressing future challenges while maintaining the rule of law and environmental sustainability.

The experience gained from implementing these systems will inform future legal and regulatory developments, contributing to a more effective, accessible, and environmentally responsible legal framework that serves the needs of India’s diverse population while meeting international standards for environmental protection and judicial transparency.

References

[1] Environment (Protection) Act, 1986.

[2] Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. (2025). Hazardous Waste Management Rules Amendment. Available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/07/04/hazardous-waste-management-rules-epr-amendment-2025/

[3] Central Pollution Control Board. (2025). Centralized EPR Portal for Plastic Packaging. Available at: https://eprplastic.cpcb.gov.in/

[4] Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, Section 15. Penalty for contravention of the provisions of the Act and the rules, orders and directions.

[5] Department of Justice, Ministry of Law and Justice. (2025). Live Streaming of Court Cases. Available at: https://doj.gov.in/live-streaming/

[6] e-Committee, Supreme Court of India. Model Rules for Live-Streaming and Recording of Court Proceedings. Available at: https://ecommitteesci.gov.in/document/model-rules-for-live-streaming-and-recording-of-court-proceedings/

[7] Supreme Court of India. (2025). Live Streaming Portal. Available at: https://www.sci.gov.in/live-streaming/

[8] Recykal. (2025). EPR Registration Guide in India 2025: Compliance, Process, and Sustainability. Available at: https://recykal.com/blog/epr-registration-guide-in-india-all-you-need-to-know-in-2025/

[9] Climeto. (2025). Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) in India: A Complete Guide for Businesses. Available at: https://climeto.com/extended-producers-responsibility-epr-in-india-a-complete-guide-for-businesses/

Legislative developments of 2025: Key Labor, Environment, and Technology Law Updates in India

Introduction

Recent months have witnessed notable legislative developments in India, particularly in labor relations, environmental protection, and technology regulation. These reforms reflect the government’s effort to modernize the legal framework while addressing emerging challenges in the digital age. New labor codes, updates to digital personal data protection rules, and evolving environmental regulations are reshaping how India governs workplace relations, protects citizen privacy, and safeguards the environment.

The legislative developments of 2025 have been marked by the phased implementation of long-awaited reforms that promise to reshape the employment landscape, enhance data security measures, and strengthen environmental compliance mechanisms. These changes carry profound implications for businesses, workers, and citizens across the country, necessitating a thorough understanding of their scope, application, and regulatory framework.

Labor Law Transformation: The New Codes Revolution

Implementation Timeline and Framework

India’s labor law reform journey has reached a critical juncture with the systematic implementation of four comprehensive labor codes that will replace 29 existing labor laws [1]. The Code on Wages 2019, Industrial Relations Code 2020, Code on Social Security 2020, and Occupational Safety, Health, and Working Conditions Code 2020 represent the most ambitious restructuring of India’s employment regulatory framework since independence.

The Ministry of Labor and Employment has established March 31, 2025, as the deadline for all 36 states and Union Territories to finalize and pre-publish harmonized draft rules for the four labor codes. This coordinated approach ensures uniform implementation across the country while allowing states to incorporate region-specific requirements within the central framework.

The implementation strategy follows a phased approach, with the first phase focusing on the Code on Wages and Social Security Code. This staged rollout allows for systematic adaptation by employers, workers, and regulatory authorities while minimizing disruption to existing employment relationships.

Wage Structure and Minimum Wage Revisions

The Code on Wages 2019 introduces revolutionary changes to India’s wage determination mechanism. Under the new framework, unskilled workers will earn a daily minimum wage of ₹783, semi-skilled workers ₹868, and highly skilled workers ₹1,035. This adjustment represents a significant increase from previous wage structures and is designed to help workers manage the rising cost of living.

The new wage code establishes a scientific methodology for wage determination that considers regional economic conditions, cost of living variations, and skill requirements. The framework moves beyond the traditional approach of state-specific minimum wage fixation to create a more standardized yet flexible system that can adapt to local economic realities while maintaining fairness across regions.

Under Section 9 of the Code on Wages 2019, the central government gains authority to fix minimum wages for scheduled employments in railway administration or major ports, mines, oilfields, and any other employment where the central government is the appropriate government. This centralization ensures consistency in wage standards for critical sectors while maintaining state autonomy for local industries.

Industrial Relations and Social Security Reforms

The Industrial Relations Code 2020 fundamentally alters the landscape of employer-employee relationships in India. The code introduces new definitions of “worker” and “industrial dispute” while streamlining dispute resolution mechanisms. Under Section 2(y) of the Industrial Relations Code 2020, a worker is defined as “any person employed in any industry to do any skilled, semi-skilled or unskilled, manual, operational, supervisory, managerial, administrative, technical or clerical work for hire or reward, whether the terms of employment be express or implied.”

The code establishes a three-tier dispute resolution system comprising conciliation officers, industrial tribunals, and National Industrial Tribunals. This structured approach aims to reduce litigation time and provide more efficient resolution of workplace disputes. The framework also introduces provisions for fixed-term employment, recognizing the changing nature of work relationships in the modern economy.

The Code on Social Security 2020 extends social security benefits to gig workers and platform workers for the first time in Indian labor law history. Section 2(35) defines a gig worker as “a person who performs work or participates in a work arrangement and earns from such activities outside of traditional employer-employee relationship.” This recognition addresses the growing gig economy and ensures that millions of platform workers receive social security protection.

Occupational Safety and Health Enhancements

The Occupational Safety, Health, and Working Conditions Code 2020 consolidates 13 existing laws related to workplace safety and working conditions. The code expands the definition of “factory” under Section 2(21) to include establishments with 20 or more workers using power or 40 or more workers without power, broadening the scope of safety regulations to cover more workplaces.

The code introduces stricter penalties for safety violations and establishes a framework for regular safety audits. Under Section 89, penalties for violations can extend up to ₹5 lakh for serious violations, with additional provisions for imprisonment in cases of gross negligence leading to worker fatalities. This enhanced penalty structure reflects the government’s commitment to ensuring workplace safety across all sectors.

Digital Personal Data Protection: India’s Privacy Revolution

Legislative Framework and Scope

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023 represents India’s first comprehensive data protection legislation, marking a significant milestone in the country’s digital governance framework [2]. The DPDP Act applies to the processing of digital personal data within the territory of India collected online or collected offline and later digitized, and is also applicable to processing digital personal data outside the territory of India if it involves offering goods or services to data principals within India.

The Act received presidential assent on August 11, 2023, and establishes a robust framework for data protection that balances individual privacy rights with business innovation requirements. The legislation draws inspiration from global best practices while incorporating India-specific considerations related to digital infrastructure and socio-economic realities.

The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) has initiated public consultation for the draft Digital Personal Data Protection Rules 2025, which will operationalize the Act’s provisions and provide detailed implementation guidelines for data fiduciaries and processors.

Data Processing Principles and Compliance Framework

The DPDP Act establishes seven fundamental principles for data processing: lawfulness, fairness, transparency, purpose limitation, data minimization, accuracy, storage limitation, and accountability. These principles create a comprehensive framework that governs how organizations collect, process, and store personal data.

Under Section 6 of the DPDP Act, data fiduciaries must obtain valid consent from data principals before processing their personal data. The Act defines consent as “any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data principal’s wishes by which she signifies her agreement to the processing of her personal data for a specified purpose.”

The legislation introduces the concept of “deemed consent” for specific categories of data processing, including voluntary provision of data by the data principal, compliance with legal obligations, medical emergencies, employment-related processing, and reasonable purposes as may be prescribed. This balanced approach ensures that essential services can continue while maintaining strong privacy protections.

Rights of Data Principals and Obligations of Data Fiduciaries

The DPDP Act grants data principals several fundamental rights, including the right to obtain information about personal data processing, seek correction and erasure of inaccurate data, exercise data portability, and withdraw consent. These rights establish individual control over personal data and align with international best practices in data protection.

Data fiduciaries bear significant obligations under the Act, including implementing appropriate technical and organizational measures to ensure data security, conducting regular audits of their data processing activities, and appointing Data Protection Officers for organizations processing large volumes of personal data. The Act also requires data fiduciaries to report personal data breaches to the Data Protection Board within prescribed timelines.

Section 17 of the DPDP Act establishes penalties ranging from ₹50 crore to ₹500 crore for various violations, reflecting the government’s intention to ensure strict compliance with data protection requirements. These substantial penalties underscore the seriousness with which the legislation treats privacy violations and data security breaches.

Cross-Border Data Transfer Regulations

The DPDP Act addresses cross-border data transfers through a notification-based approach, where the central government will specify countries and territories to which personal data may be transferred. This mechanism provides flexibility while ensuring that data transferred outside India receives adequate protection equivalent to the standards established under Indian law.

The legislation prohibits transfer of personal data to countries that may be notified as restricted territories, ensuring that geopolitical considerations and data security concerns are appropriately addressed in international data flows. This approach balances India’s digital sovereignty objectives with the practical requirements of global business operations.

Environmental Law Evolution: Strengthening Ecological Protection

Regulatory Framework Modernization

India’s environmental regulatory framework continues to evolve in response to climate change challenges and sustainable development imperatives. Recent amendments to the Environment Protection Act 1986 and updates to the National Green Tribunal procedures have strengthened the country’s environmental governance mechanisms [3].

The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change has introduced stricter environmental impact assessment requirements for industrial projects, expanding the scope of mandatory assessments to include previously exempt categories. These changes reflect India’s commitment to balancing economic development with environmental sustainability.

New guidelines for carbon credit trading and emissions monitoring have been established under the Environment Protection Act 1986, creating a framework for market-based environmental protection mechanisms. These regulations support India’s commitment to achieving net-zero emissions by 2070 while providing businesses with flexible compliance pathways.

Judicial Interpretation and Case Law Developments

Recent Supreme Court judgments have clarified the scope of environmental protection obligations and strengthened the precautionary principle in environmental decision-making. The Court’s interpretation of Article 21 of the Constitution continues to expand the right to a clean environment as a fundamental right, creating stronger legal foundations for environmental protection.

The National Green Tribunal has established important precedents regarding environmental compensation and restoration requirements, particularly in cases involving industrial pollution and ecological damage. These decisions provide clearer guidance for businesses regarding their environmental liabilities and restoration obligations.

State High Courts have also contributed to environmental jurisprudence through decisions addressing local environmental issues, creating a rich tapestry of case law that guides environmental compliance and enforcement across different regions.

Technology Regulation and Emerging Legal Frameworks

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Governance

The government has initiated development of comprehensive AI governance frameworks that address algorithmic accountability, bias prevention, and ethical AI deployment [4]. These emerging regulations will complement the DPDP Act by addressing specific challenges posed by automated decision-making systems and machine learning applications.

Draft guidelines for AI system certification and audit requirements have been circulated for stakeholder consultation, indicating the government’s proactive approach to technology regulation. These frameworks aim to ensure that AI systems deployed in critical sectors meet appropriate safety and fairness standards.

Cybersecurity and Critical Information Infrastructure

Recent amendments to the Information Technology Act 2000 have strengthened cybersecurity requirements for critical information infrastructure sectors. These changes establish mandatory security standards and incident reporting requirements for organizations operating essential digital services.

The Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-In) has issued updated guidelines for cybersecurity incident reporting and response, creating clearer obligations for organizations to maintain cybersecurity resilience. These measures support India’s digital infrastructure security while enabling rapid response to cyber threats.

Compliance Challenges and Implementation Strategies

Organizational Adaptation Requirements

The simultaneous implementation of new labor codes, data protection regulations, and environmental compliance requirements highlights recent legislative developments, presenting significant challenges for Indian businesses. Organizations must develop integrated compliance strategies that address multiple regulatory frameworks while maintaining operational efficiency.

Human resource departments face particular challenges in adapting to new labor code requirements, including revised wage calculation methods, enhanced social security obligations, and modified dispute resolution procedures. Training programs and system updates are essential for successful implementation.

Data protection compliance requires substantial investment in technology infrastructure, staff training, and process redesign. Organizations must conduct comprehensive data audits, implement privacy-by-design principles, and establish robust data governance frameworks to meet DPDP Act requirements.

Regulatory Enforcement and Monitoring Mechanisms

Government agencies are strengthening enforcement capabilities through enhanced monitoring systems, increased inspection frequencies, and improved inter-agency coordination. The establishment of specialized compliance monitoring units reflects the government’s commitment to effective implementation of new regulations.

Technology-enabled monitoring systems are being deployed to track compliance with environmental standards, labor law requirements, and data protection obligations. These systems enable real-time monitoring while reducing compliance costs for businesses and regulatory agencies.

Future Outlook and Policy Implications

Legislative Development Trends

The current wave of legislative developments indicates a broader trend toward modernizing India’s legal framework to address 21st-century challenges. Future legislative developments are likely to focus on emerging technologies, climate resilience, and social protection mechanisms.

Integration of digital technologies in regulatory compliance and enforcement is expected to accelerate, creating opportunities for more efficient and transparent regulatory processes. Businesses should prepare for increased digitalization of compliance reporting and monitoring mechanisms.

Economic and Social Impact Projections

The implementation of comprehensive labor law reforms is expected to improve working conditions for millions of Indian workers while providing businesses with greater flexibility in employment arrangements. The long-term economic impact will depend on successful implementation and stakeholder adaptation.

Data protection regulations will likely accelerate the growth of India’s digital economy by enhancing consumer trust and creating competitive advantages for compliant businesses. International businesses are expected to increase their India investments as data protection standards align with global requirements.

Environmental regulations will drive innovation in clean technologies and sustainable business practices, potentially positioning India as a leader in green technology development and deployment. The economic benefits of environmental compliance are expected to outweigh short-term implementation costs.

Conclusion

The legislative developments examined in this analysis represent a fundamental transformation of India’s regulatory landscape across multiple domains. The implementation of new labor codes, data protection regulations, and environmental standards creates both opportunities and challenges for businesses, workers, and citizens.

Successful navigation of this evolving regulatory environment requires proactive compliance strategies, stakeholder engagement, and continuous monitoring of legislative developments. Organizations that invest early in compliance capabilities and adopt best practices will be better positioned to thrive in India’s modernized regulatory framework.

The government’s commitment to phased implementation and stakeholder consultation provides opportunities for businesses to adapt gradually while ensuring effective compliance. However, the scale and complexity of these changes demand sustained attention and resources from all stakeholders.

As India continues its journey toward becoming a developed nation by 2047, these regulatory reforms will play a crucial role in creating the institutional framework necessary for sustained economic growth, social progress, and environmental sustainability. The success of these initiatives will depend on effective implementation, stakeholder cooperation, and continuous refinement based on practical experience.

References

[1] Ministry of Labour & Employment. (2025). Labour Codes Implementation Update. Government of India. https://labour.gov.in/labour-codes

[2] Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology. (2023). Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023. Government of India.

[3] Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. (2025). Environmental Law Updates and Implementation Guidelines. Government of India. https://moef.gov.in/

[4] India-Briefing. (2025). Indian States, UTs to Finalize Labor Codes Rules by March 2025. https://www.india-briefing.com/news/indian-states-uts-to-finalize-labor-codes-rules-by-march-2025-35588.html/

[5] EY India. (2024). Decoding the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023. https://www.ey.com/en_in/insights/cybersecurity/decoding-the-digital-personal-data-protection-act-2023

[6] PRS Legislative Research. (2024). The Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2023. https://prsindia.org/billtrack/digital-personal-data-protection-bill-2023

[7] Privacy World. (2025). The Impact of India’s New Digital Personal Data Protection Rules. https://www.privacyworld.blog/2025/04/the-impact-of-indias-new-digital-personal-data-protection-rules/

[8] Global Privacy Blog. (2024). India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023 vs. the GDPR: A Comparison. https://www.globalprivacyblog.com/2023/12/indias-digital-personal-data-protection-act-2023-vs-the-gdpr-a-comparison/

[9] Lexology. (2024). Update on implementation of new labour codes. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=5fd6969e-48ad-458a-86e0-9025e3da840e

Supreme Court Expands Prisoner Appellate Rights: Gutierrez v. Saenz and the 2025 Revolution in Post-Conviction DNA Testing

Introduction

The United States Supreme Court’s recent jurisprudence has significantly advanced the constitutional rights of prisoners seeking to challenge their convictions through the appellate process, strengthening prisoner appellate rights across the country. Most notably, the landmark decision in Gutierrez v. Saenz [1] decided on June 26, 2025, represents a pivotal moment in criminal justice reform, establishing crucial precedents for prisoner access to DNA evidence and post-conviction relief. This decision, alongside other recent orders, demonstrates the Court’s commitment to ensuring that fundamental due process rights extend meaningfully to incarcerated individuals asserting their prisoner appellate rights.

The Supreme Court’s approach to criminal appeals has evolved considerably, particularly in addressing systemic barriers that have historically prevented prisoners from mounting effective challenges to their convictions. These developments occur against the backdrop of mounting evidence regarding wrongful convictions and the critical role of scientific evidence, particularly DNA testing, in ensuring judicial accuracy. The Court’s recent orders reflect a nuanced understanding of how procedural obstacles can undermine substantive constitutional protections.

The Gutierrez v. Saenz Decision: A Watershed Moment

Background and Factual Context

In Gutierrez v. Saenz, the Supreme Court confronted a fundamental question about prisoner standing to challenge state DNA testing procedures [2]. Ruben Gutierrez, convicted in 1999 for the murder of Escolastica Harrison and sentenced to death, sought post-conviction DNA testing to prove that while he participated in robbing Harrison, he was not involved in her murder and therefore ineligible for the death penalty under Texas law.

The case presented a classic Catch-22 scenario that exemplifies the procedural barriers facing prisoners. Texas Chapter 64 of the Code of Criminal Procedure entitles convicted persons to DNA testing only if such testing would likely result in a not guilty verdict [3]. However, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals held that even if DNA testing showed Gutierrez never entered Harrison’s house, he could still receive the death penalty due to his role in the robbery under Texas’s law of parties.

The Supreme Court’s Analysis

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, writing for the 6-3 majority, addressed the standing doctrine’s application to prisoner rights cases with unprecedented clarity [4]. The Court held that Gutierrez had standing to challenge the constitutionality of Texas’s DNA testing procedures, finding that the state’s position created an unconstitutional burden on the right to seek post-conviction relief.

The majority opinion emphasized the fundamental unfairness of allowing prisoners to file habeas corpus petitions challenging their death sentences while simultaneously precluding them from obtaining DNA testing to support those petitions. The Court stated that this procedural framework violated basic due process principles by creating insurmountable evidentiary obstacles for prisoners seeking to prove their constitutional claims.

Constitutional Implications

The decision establishes several critical constitutional principles. First, it clarifies that procedural injuries – harm caused by the denial of access to evidence necessary for constitutional challenges – constitute sufficient injury for Article III standing purposes. This represents a significant expansion of traditional standing doctrine in the prisoner rights context.

Second, the Court recognized that access to potentially exonerating evidence is not merely a statutory privilege but implicates fundamental constitutional protections. The decision builds upon earlier precedents establishing that the Constitution requires states to provide meaningful procedures for post-conviction relief, particularly in capital cases where the stakes are literally life and death.

Statutory Framework Governing Criminal Appeals

Federal Appellate Procedures

The federal system governing criminal appeals operates under several key statutes that establish time limits and procedural requirements. Under 28 U.S.C. § 2107, appeals to courts of appeals must generally be filed within 30 days after entry of judgment in criminal cases [5]. For petitions for writs of certiorari to the Supreme Court, 28 U.S.C. § 2101 establishes a 90-day deadline, with possible extensions of up to 60 days for good cause shown [6].

The Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, particularly Rule 4, provide additional procedural safeguards by specifying exactly when appeals must be filed and what constitutes proper notice [7]. These rules recognize that technical procedural requirements should not operate to deny prisoners meaningful access to appellate review, particularly when delays may result from institutional factors beyond the prisoner’s control.

State Criminal Procedure Codes

Most states have adopted similar temporal frameworks for criminal appeals, though with significant variations in their application to different categories of cases. The Indian Code of Criminal Procedure serves as an instructive comparative example, with Section 374 establishing the general right to appeal from convictions [8]. Under this framework, any person convicted by a Sessions Judge or Additional Sessions Judge, or any person sentenced to imprisonment for more than seven years, has the right to appeal to the High Court.

Section 384 of the Criminal Procedure Code provides additional protections by establishing specific time limits for filing appeals and creating mechanisms for extending these deadlines in cases where prisoners face institutional barriers to timely filing [9]. These provisions recognize that incarcerated individuals may face unique challenges in preparing and filing appeals within standard timeframes.

Recent Supreme Court Orders and Their Impact

Enhanced Standing Requirements

Following Gutierrez v. Saenz, lower federal courts have begun applying more liberal standing requirements in prisoner rights cases. The decision has particular significance for cases involving access to evidence, as it establishes that prisoners need not demonstrate that relief would definitely result in overturning their convictions, but merely that access to evidence could meaningfully support their constitutional challenges.

This shift represents a departure from previous, more restrictive approaches that often required prisoners to make nearly impossible showings of likelihood of success before gaining access to potentially exonerating evidence. The new framework recognizes that the purpose of post-conviction proceedings is to test the validity of convictions, not to relitigate guilt or innocence under impossible evidentiary standards.

DNA Testing and Scientific Evidence

The Supreme Court’s recent orders reflect growing recognition of scientific evidence’s crucial role in ensuring accurate criminal convictions. Beyond Gutierrez v. Saenz, the Court has issued several orders that facilitate prisoner access to advanced forensic testing techniques that were unavailable at the time of their original trials.

These developments acknowledge the rapidly evolving nature of forensic science and the potential for new testing methods to provide crucial evidence bearing on conviction validity. The Court’s approach recognizes that rigid application of traditional procedural barriers could result in the execution or continued imprisonment of actually innocent individuals.

Procedural Due Process Enhancements

Recent Supreme Court orders have strengthened procedural due process protections for prisoners throughout the appellate process. These enhancements include clarifications regarding adequate assistance of counsel during post-conviction proceedings, requirements for meaningful notice of appellate deadlines, and protections against institutional delays that could prejudice prisoner appeals.

The Court has been particularly attentive to situations where prison conditions or administrative failures could prevent prisoners from exercising their appellate rights effectively. This includes recognition that limited library access, mail delays, and other institutional factors cannot serve as the basis for denying constitutional protections.

Regulatory Framework and Implementation

Federal Court Administration

The implementation of enhanced prisoner appellate rights operates through established federal court administrative mechanisms. The Administrative Office of the United States Courts has developed specific protocols for handling prisoner appeals that account for the unique challenges facing incarcerated litigants.

These protocols include expedited review procedures for capital cases, special forms designed for pro se prisoner litigants, and coordination mechanisms between federal courts and correctional institutions to ensure timely document delivery. The regulatory framework recognizes that effective prisoner appellate rights require more than formal procedural availability – they require practical accessibility.

State Implementation Mechanisms

States have varied considerably in their implementation of enhanced prisoner appellate rights. Progressive jurisdictions have established dedicated post-conviction review units, expanded access to legal libraries and research resources, and created electronic filing systems that accommodate the practical constraints of prison environments.

Other jurisdictions have been slower to adapt, creating potential constitutional vulnerabilities where state procedures fail to provide the meaningful access that federal constitutional principles require. The Supreme Court’s recent orders suggest that such disparities may face increasing federal constitutional scrutiny.

Case Law Development and Precedential Impact

Building on Established Precedents

The Supreme Court’s recent orders build upon a substantial body of precedent establishing prisoner appellate rights to meaningful post-conviction review. Cases like Brady v. Maryland established prosecutorial obligations to disclose exculpatory evidence, while Strickland v. Washington created frameworks for evaluating the adequacy of defense representation.

Gutierrez v. Saenz extends these principles by recognizing that post-conviction access to evidence is essential for making these earlier protections meaningful. The decision acknowledges that constitutional rights established at trial become hollow if prisoners cannot subsequently obtain evidence necessary to demonstrate violations of those rights.

Circuit Court Applications

Federal circuit courts have begun applying the principles from Gutierrez v. Saenz in diverse contexts beyond DNA testing. These applications include cases involving access to police investigation files, expert witness testimony, and other forms of evidence that could support constitutional challenges to convictions.

The emerging pattern suggests that courts are moving toward a more holistic understanding of what meaningful post-conviction review requires. Rather than treating each evidentiary request in isolation, courts are increasingly evaluating whether prisoners have reasonable access to the evidence necessary to present their constitutional claims effectively.

Challenges and Limitations

Resource Constraints

Despite constitutional mandates for meaningful post-conviction review, many jurisdictions face significant resource constraints that limit their ability to provide adequate appellate protections for prisoners. These constraints affect everything from court-appointed counsel availability to laboratory capacity for DNA testing.

The Supreme Court’s recent orders implicitly recognize these practical challenges while maintaining that resource limitations cannot justify constitutional violations. This creates ongoing tension between constitutional mandates and practical implementation capabilities that continues to shape the development of prisoner appellate rights.

Institutional Resistance

Some state systems have shown resistance to implementing enhanced prisoner appellate protections, viewing them as imposing excessive administrative burdens or undermining finality in criminal cases. This resistance has led to continued litigation over the scope and application of constitutional protections established in recent Supreme Court orders.

The Court’s approach suggests that such resistance will not justify failure to provide constitutionally adequate procedures, but the practical implementation of this principle remains challenging in jurisdictions with limited resources or philosophical opposition to expanded prisoner rights.

Future Implications and Developments

Expanding Access to Scientific Evidence

The principles established in Gutierrez v. Saenz seem likely to extend beyond DNA testing to other forms of scientific evidence that could bear on conviction validity. This could include advances in fingerprint analysis, ballistics testing, digital forensics, and other evolving scientific disciplines.

The Court’s approach suggests recognition that the constitutional right to meaningful post-conviction review must evolve alongside scientific capabilities. This creates an ongoing obligation for courts to evaluate whether existing procedures provide adequate access to potentially exonerating evidence using current scientific methods.

Technology and Electronic Filing

Recent Supreme Court orders have also addressed the role of technology in facilitating prisoner access to appellate procedures. Electronic filing systems, video conferencing for court appearances, and digital access to legal research materials all represent areas where technological advances could enhance constitutional protections.

The regulatory framework continues to evolve to accommodate these technological possibilities while ensuring that digital divides do not create new barriers to constitutional protections. This balance between technological enhancement and universal accessibility remains an ongoing challenge.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s recent orders on timely criminal appeals represent a significant advancement in ensuring meaningful access to justice for prisoners. The landmark Gutierrez v. Saenz decision, in particular, establishes crucial precedents that recognize procedural barriers cannot be allowed to undermine fundamental constitutional protections.

These developments reflect the Court’s sophisticated understanding of how technical procedural requirements can operate to deny substantive constitutional rights. By clarifying standing requirements, expanding access to scientific evidence, and strengthening procedural due process protections, the Court has created a framework that better ensures the accuracy and fairness of criminal convictions.

The implementation of these enhanced protections continues to face practical challenges, including resource constraints and institutional resistance. However, the constitutional principles established in recent orders provide a foundation for continued development of more effective post-conviction review procedures.

As scientific capabilities continue to advance and understanding of wrongful convictions deepens, the frameworks established in these recent Supreme Court orders will likely prove essential for maintaining public confidence in the criminal justice system. The Court’s commitment to meaningful appellate access represents not just a protection for individual prisoners, but a crucial safeguard for the integrity of criminal justice itself.

The path forward requires continued attention to both constitutional principles and practical implementation challenges. The Supreme Court’s recent orders provide the constitutional framework, but realizing their promise requires sustained commitment from courts, legislatures, and correctional systems across the country. Only through such coordinated effort can the enhanced access to justice envisioned in these landmark decisions become a practical reality for all prisoners seeking to challenge their convictions.

References

[1] Gutierrez v. Saenz, 606 U.S. ___ (2025), available at https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/606/23-7809/

[2] U.S. Supreme Court Rules in Favor of Texas Death Row Prisoner Seeking DNA Testing, Death Penalty Information Center (June 27, 2025), https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/u-s-supreme-court-rules-in-favor-of-texas-death-row-prisoner-seeking-dna-testing

[3] Gutierrez v. Saenz: Standing in Cases Challenging State Post-Conviction DNA Testing Laws, Constitution Annotated, Congress.gov, https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/intro.9-3-13/ALDE_00000124/

[4] US Supreme Court allows Texas death row inmate to sue over state’s DNA testing procedure, JURIST News (June 29, 2025), https://www.jurist.org/news/2025/06/us-supreme-court-allows-texas-death-row-inmate-to-sue-over-states-dna-testing-procedure/

[5] 28 U.S.C. § 2107 – Time for appeal to court of appeals, Legal Information Institute, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/28 /2107

[6] 28 U.S.C. § 2101 – Supreme Court; time for appeal or certiorari, Legal Information Institute, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/28/2101

[7] Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure Rule 4, Legal Information Institute, https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frap/rule_4

[8] Section 374 in The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, Indian Kanoon, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1903086/

[9] Section 374 CrPC, iPleaders Blog (December 26, 2022), https://blog.ipleaders.in/section-374-crpc/

Authorized by Rutvik Desai

Bombay High Court Child Custody Ruling: Prioritizing Child Welfare Over Personal Law in Aurangabad Bench

Introduction

The Bombay high court child custody ruling delivered by the Aurangabad Bench on July 21, 2025, fundamentally reinforced the paramount importance of child welfare over religious personal laws in custody disputes [1]. This pivotal judgment granted custody of a nine-year-old Muslim boy to his mother, directly challenging traditional interpretations of Muslim personal law that typically vest custody of male children above seven years with their fathers. The judgment represents a significant legal precedent that prioritizes the best interests of the child principle over rigid adherence to personal law provisions

The case of Sau Khalida v. Ismile has emerged as a watershed moment in Indian family law jurisprudence, demonstrating how courts must navigate the complex intersection between constitutional principles of child welfare and religious personal laws [2]. The judgment underscores the judiciary’s commitment to ensuring that legal technicalities do not override fundamental considerations of child safety, emotional wellbeing, and developmental needs.

Background and Case Details

The dispute originated when a District Judge in Nilanga had previously ruled in December 2023 that custody of the nine-year-old boy should be transferred to his father, following traditional principles of Muslim personal law [3]. Under conventional interpretation of Islamic jurisprudence, male children above the age of seven are typically placed under paternal custody, as fathers are considered better equipped to provide religious education and prepare boys for their societal roles.

However, the mother challenged this decision before the Bombay High Court’s Aurangabad Bench, arguing that her son’s welfare and emotional stability would be better served by remaining in her custody. The case presented compelling evidence regarding the child’s attachment to his mother and the stability of his current living arrangements. The court was required to carefully balance respect for personal law traditions against constitutional mandates protecting child welfare.

The factual matrix revealed that the child had been living with his mother and had developed strong emotional bonds and stability in that environment. Evidence presented before the court indicated that disrupting this arrangement might cause psychological trauma to the minor, despite technical compliance with traditional custody norms under Muslim personal law.

Legal Framework Governing Child Custody in India

Constitutional Foundation

The Indian Constitution provides the fundamental framework for child protection through various provisions that prioritize children’s rights and welfare. Article 15(3) specifically empowers the state to make special provisions for children, while Article 21 guarantees the right to life and personal liberty, which has been interpreted by courts to include the right to a healthy and safe childhood environment.

The constitutional philosophy emphasizes that children are not mere property of their parents but individuals with distinct rights that must be protected by the state. This principle forms the bedrock upon which all child custody determinations must be made, regardless of personal law considerations.

The Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956

Although this case involved Muslim personal law, the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956 provides crucial insights into how Indian legislation approaches child custody matters. Section 6 of the Act establishes the hierarchy of natural guardianship, stating that “the natural guardian of a Hindu minor, in respect of the minor’s person as well as in respect of the minor’s property (excluding his or her undivided interest in joint family property), is the father, and after him, the mother” [4].

However, Section 6(a) creates an important exception: “the custody of a minor who has not completed the age of five years shall ordinarily be with the mother.” This provision recognizes the special bond between young children and their mothers, acknowledging developmental psychology principles that emphasize maternal attachment during early childhood.

Section 17(2) of the Act provides the court with discretionary power to override natural guardianship principles when child welfare demands it. The section empowers courts to appoint guardians other than natural guardians “if the court is of opinion that it is for the welfare of the minor” [5].

Muslim Personal Law and Custody Principle

Muslim personal law traditionally governs custody matters for Muslim families through concepts of hizanat (physical custody) and wilayat (guardianship). Under classical Islamic jurisprudence, mothers typically retain custody of young children during the hizanat period, but this custody transfers to fathers as children mature, particularly for male children around age seven.

The principle behind this traditional arrangement stems from the belief that fathers are better positioned to provide religious education and prepare male children for their social responsibilities. However, modern legal interpretation recognizes that these principles must be applied flexibly, considering contemporary understanding of child psychology and welfare.

Reasoning and Analysis of the Bombay High Court Child Custody Ruling

Distinction Between Custody and Guardianship

The Bombay High Court made a crucial distinction between hizanat (physical custody) and wilayat-e-nafs (guardianship of the person). The judgment clarified that “the physical custody and day-to-day upbringing is the hizanat. All other aspects than hizanat would fall under wilayat” [6]. This distinction allowed the court to grant physical custody to the mother while acknowledging the father’s continuing role in major decisions affecting the child’s welfare.

This nuanced interpretation demonstrates judicial sophistication in applying personal law principles while ensuring practical arrangements serve the child’s best interests. The court recognized that rigid application of traditional custody rules might not always align with modern understanding of child development and psychological needs.

Application of the Best Interests Principle

The court emphasized that when personal law conflicts with child welfare, the latter must prevail. Drawing from established precedents, the judgment reinforced that “the welfare of the child is the paramount consideration” in all custody determinations. This principle derives from both constitutional mandates and international conventions on children’s rights that India has ratified.

The court evaluated various factors including the child’s emotional attachment, educational continuity, social environment, and overall stability. Evidence presented during proceedings indicated that the child had developed strong bonds with his mother and that disrupting this arrangement might cause significant emotional distress.

Judicial Precedents and Legal Authority

The Bombay High Court relied heavily on the Supreme Court’s judgment in Gaurav Nagpal vs. Sumedha Nagpal (2009) 1 SCC 42, which established that courts must prioritize child welfare over technical legal provisions [7]. The Supreme Court had observed that “the paramount consideration is the welfare and interest of the child and not the rights of the parents under the personal law.”

This precedent provided crucial legal foundation for the Aurangabad Bench to override traditional personal law interpretations in favor of child welfare considerations. The judgment demonstrates how higher court precedents create binding authority that enables lower courts to make welfare-oriented decisions even when they conflict with personal law traditions.

Regulatory Framework and Implementation Mechanisms

Family Court Jurisdiction and Procedures

Family courts established under the Family Courts Act, 1984, have exclusive jurisdiction over child custody matters. These specialized courts are designed to handle family disputes with greater sensitivity and expertise than regular civil courts. The Act mandates that family courts must prioritize reconciliation and child welfare in all proceedings.

Section 9 of the Family Courts Act specifically requires courts to “make endeavour for settlement” and emphasizes the welfare of children in all family-related matters. This legislative framework provides the procedural foundation for courts to prioritize child welfare over technical legal requirements.

Role of Child Welfare Committees

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 establishes Child Welfare Committees in every district to ensure child protection. While these committees primarily handle cases involving children in need of care and protection, they also provide crucial inputs in custody disputes where child welfare is a primary concern.

These committees, comprising child welfare experts, social workers, and legal professionals, can provide courts with professional assessments of what arrangements would best serve a child’s interests. Their recommendations carry significant weight in judicial decision-making processes.

Comparative Analysis with Other Jurisdictions

International Best Practices

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which India has ratified, establishes the principle that “in all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration” [8].

This international framework provides additional legal authority for Indian courts to prioritize child welfare over personal law considerations. The principle has been consistently applied across various jurisdictions, demonstrating global consensus on the paramount importance of child welfare.

Evolution of Indian Jurisprudence

Indian courts have gradually evolved their approach to child custody from property-based concepts toward welfare-oriented principles. Early judgments often treated children as extensions of parental rights, but contemporary jurisprudence recognizes children as independent individuals with distinct rights requiring protection.

This evolution reflects broader social transformation and improved understanding of child psychology and development. Courts increasingly recognize that traditional custody arrangements must be evaluated against modern welfare standards rather than applied mechanically.

Implications for Muslim Family Law

Modernization of Personal Law Interpretation

The Bombay High Court Child Custody judgement represents a significant step in modernizing personal law interpretation without abandoning religious principles entirely. The court’s approach demonstrates how traditional legal concepts can be reinterpreted through contemporary welfare lenses while maintaining respect for religious traditions.

This balanced approach may provide a template for future cases involving conflicts between personal law and child welfare. Rather than rejecting personal law entirely, courts can apply these principles flexibly to ensure they serve their ultimate purpose of promoting family and child welfare.

Impact on Custody Practices

The judgment may influence how Muslim families approach custody arrangements, encouraging greater consideration of individual circumstances rather than automatic application of traditional rules. Legal practitioners may need to develop new strategies that emphasize welfare evidence rather than relying solely on personal law precedents.

This shift requires family law practitioners to develop expertise in child psychology, social work principles, and welfare assessment techniques. The emphasis on evidence-based welfare determinations may lead to more professional and scientific approaches to custody disputes.

Challenges and Criticisms

Balancing Religious Freedom and Child Welfare

Critics argue that prioritizing child welfare over personal law may undermine religious freedom and community autonomy. Some religious leaders express concern that such judicial approaches might erode traditional family structures and religious practices.

However, supporters contend that religious freedom cannot be absolute when it conflicts with fundamental rights of children. The challenge lies in developing approaches that respect religious traditions while ensuring adequate child protection.

Implementation and Enforcement Issues

Practical implementation of welfare-oriented custody decisions may face resistance from communities that strongly adhere to traditional practices. Courts may need to develop mechanisms for ensuring compliance with custody orders that conflict with community expectations.

Social workers, counselors, and child welfare professionals play crucial roles in supporting families through these transitions and ensuring that court orders serve their intended welfare purposes.

Future Directions and Legal Development

Legislative Reform Possibilities

The judgment highlights potential need for legislative reforms that provide clearer guidance on balancing personal law and child welfare considerations. Parliament might consider comprehensive family law reforms that establish uniform child welfare standards while respecting religious diversity.