Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

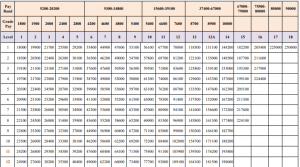

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

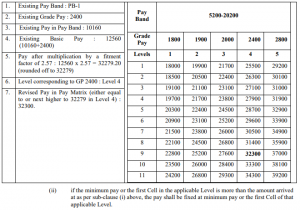

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

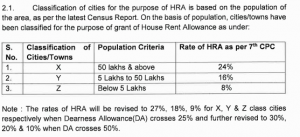

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

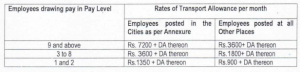

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Registered Wills Validity Affirmed by Supreme Court: Burden of Proof in Testamentary Disputes Clarified

Introduction

The validity of registered wills has been a subject of extensive judicial scrutiny in Indian courts, particularly regarding the burden of proof required in testamentary disputes. Recent Supreme Court jurisprudence has provided significant clarity on this matter, establishing that registered wills carry a presumption of genuineness and due execution. This legal development marks a crucial shift in how courts approach testamentary disputes, fundamentally altering the evidential burden placed on parties challenging the validity of registered wills.

The landmark judgment in Metpalli Lasum Bai (since dead) & Others v. Metpalli Muthaih (dead) by Legal Heirs [1] has reinforced the presumption of validity attached to registered wills, creating substantial implications for inheritance law practice in India. This decision builds upon decades of jurisprudential evolution concerning testamentary capacity, due execution, and the evidentiary standards required in succession matters.

Legal Framework Governing Will Registration

Statutory Provisions Under the Registration Act, 1908

The registration of wills in India is governed primarily by the Registration Act, 1908, which provides the legal framework for document registration and the presumptions that arise therefrom. Section 35 of the Registration Act establishes that when a document is properly registered, there exists a presumption regarding its valid execution [2]. This presumption extends to wills, creating a foundational legal principle that supports the validity of registered wills and establishes their inherent credibility.

The Registration Act mandates that for optional registration, the registrar must be satisfied about the document’s authenticity before allowing registration. This preliminary verification process adds a layer of official scrutiny that strengthens the presumption of genuineness. The registering officer’s role involves examining the document, verifying the identity of the executant, and ensuring compliance with statutory requirements before admitting the document to registration.

Under Section 59 of the Registration Act, registration of wills is optional rather than mandatory. However, when a testator chooses to register their will, the document gains significant legal advantages in terms of proving its authenticity and validity of registered wills in testamentary disputes. The registration process involves the testator appearing before the registering officer, acknowledging the execution of the will, and having the document entered in official records with proper attestation.

Indian Succession Act, 1925 and Testamentary Requirements

The Indian Succession Act, 1925 governs the substantive law relating to wills and succession. Section 63 of the Act prescribes the essential requirements for valid execution of wills, including the testator’s signature or mark, attestation by two witnesses, and the witnesses’ signatures in the testator’s presence [3]. These statutory requirements form the foundation for determining testamentary validity, regardless of whether the will is registered.

Section 68 of the Act deals specifically with the proof of wills, establishing that the onus lies on the propounder to prove that the will was duly executed according to law. However, recent Supreme Court jurisprudence has clarified that when a will is registered, this burden is significantly modified, with the presumption of validity arising from registration itself.

The Act also addresses issues of testamentary capacity under Sections 59-61, requiring that the testator be of sound mind and not under undue influence or coercion at the time of execution. These provisions work in conjunction with the Registration Act to create a comprehensive framework for testamentary validity.

Supreme Court’s Position on Registered Wills

The Metpalli Lasum Bai Judgment and Its Impact

The Supreme Court’s recent decision in Metpalli Lasum Bai (since dead) & Others v. Metpalli Muthaih (dead) by Legal Heirs represents a significant clarification of the law regarding registered wills [1]. The Court explicitly held that a registered will carries a presumption of due execution and genuineness, fundamentally shifting the burden of proof to the party challenging the will’s validity.

This judgment addressed a property dispute involving ancestral lands measuring 18 acres and 6 guntas located in Telangana. The case arose from competing claims among the legal heirs of late Metpalli Rajanna, with the validity of a registered will becoming the central issue. The Supreme Court’s analysis focused on the legal significance of registration and its impact on evidentiary presumptions in testamentary disputes.

The Court observed that when a will is a registered document, there exists a presumption regarding its genuineness, and the burden lies heavily on the party disputing its existence. This principle represents a departure from earlier approaches that required elaborate proof even for registered wills, streamlining the process for beneficiaries while maintaining appropriate safeguards against fraud.

Evolution of Judicial Approach

The Supreme Court’s approach to registered wills has evolved considerably over recent years. In contrast to the Metpalli Lasum Bai decision, earlier judgments such as Leela v. Muruganantham had emphasized that mere registration does not attach a stamp of validity to a will [4]. This apparent contradiction highlights the nuanced nature of testamentary law and the Court’s efforts to balance the benefits of registration with the need for proper scrutiny.

The evolution reflects a growing recognition that the registration process itself provides sufficient safeguards to warrant a presumption of validity. The registering officer’s preliminary verification, combined with the formal requirements of the Registration Act, creates a framework that supports the presumption while allowing for rebuttal when genuine concerns about validity arise.

Recent judicial trends indicate a move toward greater reliance on documentary evidence and formal procedures, reducing the emphasis on witness testimony and elaborate proof requirements that often led to prolonged litigation. This shift acknowledges the practical challenges faced by beneficiaries in proving wills, particularly when significant time has elapsed since execution.

Burden of Proof in Testamentary Disputes

Traditional Approach and Its Limitations

Historically, Indian courts required the propounder of a will to establish its validity through comprehensive evidence, including proof of due execution, testamentary capacity, and absence of fraud or undue influence. This approach placed a substantial burden on beneficiaries, often requiring them to produce witnesses to execution, handwriting experts, and extensive circumstantial evidence to establish validity.

The traditional burden of proof framework created several practical difficulties. Witnesses to will execution might be deceased or unavailable after significant periods, handwriting analysis could be inconclusive, and the requirement for positive proof of all elements often led to lengthy and expensive litigation. These challenges were particularly acute in cases involving elderly testators where questions of mental capacity arose.

Furthermore, the traditional approach did not adequately account for the protection offered by the registration process itself. The preliminary verification conducted by registering officers, combined with the formal requirements for registration, provided safeguards that were not reflected in the evidentiary standards applied by courts.

Current Legal Position Post-Metpalli

Following the Metpalli Lasum Bai judgment, the legal position regarding registered wills has been clarified significantly. The Supreme Court has established that registration creates a rebuttable presumption of validity, shifting the primary burden to those challenging the will. This presumption covers both the due execution of the will and its genuineness, encompassing the key elements typically required for testamentary validity [1].

The current approach requires challengers to demonstrate specific grounds for questioning the will’s validity, such as evidence of fraud, forgery, lack of testamentary capacity, or undue influence. Mere suspicion or general challenges to the will’s authenticity are insufficient to overcome the presumption arising from registration.

This shift has practical implications for legal practitioners and beneficiaries. Propounders of registered wills now enjoy a stronger starting position, while challengers must present concrete evidence supporting their contentions. The change reduces the likelihood of frivolous challenges while maintaining appropriate protection against genuine cases of testamentary fraud.

Evidentiary Standards and Procedural Requirements

The Supreme Court has clarified that the presumption attached to registered wills does not create an irrebuttable presumption of validity. However, the standard of proof required to overcome this presumption is substantial. Challengers must present clear and convincing evidence that calls into question the will’s authenticity or validity.

Courts now apply a heightened scrutiny standard when evaluating challenges to registered wills. The presumption of validity means that neutral or inconclusive evidence typically favors the propounder, while challengers must present evidence that positively establishes grounds for invalidity.

The procedural implications include modified pleading requirements, with challengers needing to specify particular grounds for questioning validity rather than making general denials. Discovery and evidence gathering must focus on concrete allegations rather than broad fishing expeditions for potential weaknesses in the will’s execution.

Registration Process and Legal Safeguards

Role of Registering Officers

The registration process involves multiple safeguards that support the presumption of validity for registered wills. Registering officers are required to verify the identity of the executant, ensure the presence of required witnesses, and examine the document for basic compliance with legal requirements. This preliminary verification process adds an official imprimatur that strengthens the document’s credibility.

Section 35 of the Registration Act requires registering officers to be satisfied about the document’s proper execution before admitting it to registration [2]. This requirement creates a filtering mechanism that excludes obviously defective or suspicious documents from the benefits of registration. While the officer’s examination is not exhaustive, it provides a meaningful safeguard against clear cases of fraud or improper execution.

The registration process also creates a permanent official record of the will’s execution, including details about the parties present, the date and time of registration, and any observations made by the registering officer. This documentation provides valuable evidence for later proceedings and reduces the likelihood of successful challenges based on fabricated claims about execution circumstances.

Verification Mechanisms and Documentation

Modern registration practices incorporate various verification mechanisms designed to enhance the reliability of registered documents. These include requirements for proper identification of parties, verification of witness credentials, and maintenance of detailed records regarding the registration process. Such mechanisms support the legal presumption by ensuring that registered wills have undergone meaningful scrutiny.

The documentation requirements under the Registration Act ensure that comprehensive records are maintained regarding will registration. These records include copies of the original will, details of all parties present during registration, and any special circumstances noted by the registering officer. This documentation provides a foundation for the legal presumption and valuable evidence for resolving disputes.

Electronic registration systems increasingly used across India have enhanced the reliability of registration records while reducing the possibility of tampering or manipulation. Digital records provide additional security and accessibility, supporting the policy rationale for attaching presumptions to registered documents.

Judicial Precedents and Case Law Analysis

Landmark Supreme Court Decisions

Beyond the Metpalli Lasum Bai judgment, several other Supreme Court decisions have contributed to the current legal framework governing registered wills. These cases demonstrate the evolving judicial understanding of the relationship between registration and testamentary validity.

In H. Venkatachala Iyengar v. B.N. Thimmajamma, the Supreme Court examined issues relating to will validity and the application of survivorship rules among legatees [5]. While this case predates recent developments, it illustrates the Court’s longstanding concern with ensuring proper testamentary procedures while facilitating legitimate succession arrangements.

The jurisprudential development reflects a balance between protecting genuine testamentary intentions and preventing fraud. Courts have consistently emphasized that registration provides important safeguards while maintaining that these safeguards create presumptions rather than absolute immunity from challenge.

High Court Perspectives and Regional Variations

Various High Courts across India have contributed to the development of testamentary law, with some regional variations in approach. However, the Supreme Court’s recent clarification in Metpalli Lasum Bai provides binding precedent that resolves conflicting approaches and establishes uniform standards for registered wills [1].

The uniformity achieved through Supreme Court guidance is particularly important in succession matters, where families may have connections to multiple states and where property disputes can involve jurisdictional complications. Consistent application of presumptions relating to registered wills reduces forum shopping and ensures predictable outcomes.

Regional High Courts have generally aligned their approaches with Supreme Court guidance, though some variations in application continue to exist. The binding nature of Supreme Court precedent ensures that the presumption favoring registered wills applies uniformly across Indian courts.

Practical Implications for Legal Practice

Strategic Considerations for Will Drafting

The Supreme Court’s clarification regarding registered wills has significant implications for estate planning and will drafting practices. Legal practitioners now have strong incentives to recommend registration for their clients’ wills, given the enhanced protection and reduced litigation risk that registration provides.

The strategic advantages of registration extend beyond mere evidentiary presumptions. Registered wills are less vulnerable to claims of loss or destruction, more difficult to forge or manipulate, and benefit from official documentation that supports their authenticity. These practical benefits complement the legal presumptions established by recent Supreme Court jurisprudence.

Estate planning practices should now incorporate registration as a standard recommendation rather than an optional consideration. The relatively modest cost and administrative burden of registration are substantially outweighed by the legal advantages, particularly for high-value estates or situations where family disputes are anticipated.

Impact on Succession Planning

The enhanced status of registered wills has broader implications for succession planning strategies. Families can now rely more confidently on registered testamentary documents, reducing the need for complex trust structures or other arrangements designed to avoid testamentary challenges.

The reduced litigation risk associated with registered wills makes them more attractive vehicles for wealth transfer, particularly for business families or individuals with substantial assets. The predictability of outcomes under the new legal framework facilitates more efficient succession planning and reduces the uncertainty that previously discouraged reliance on wills.

Professional advisors in fields such as wealth management, tax planning, and family business succession should update their practices to reflect the enhanced reliability of registered wills. This change may influence recommendations regarding estate structure and wealth transfer strategies.

Contemporary Challenges and Future Directions

Balancing Presumptions with Protection Against Fraud

While the Supreme Court’s approach to registered wills provides important benefits, it also raises questions about maintaining adequate protection against sophisticated fraud or undue influence. The challenge lies in balancing the benefits of presumptions with the need to detect and prevent genuine cases of testamentary abuse.

Courts must remain vigilant in cases where evidence suggests registration may have been obtained through fraudulent means or where the testator’s capacity or free will appears compromised. The presumption of validity should not become a shield for protecting illegitimate wills that happen to be registered.

The legal system must continue evolving to address emerging challenges such as elder abuse, digital fraud, and other contemporary threats to testamentary integrity. The framework established by recent Supreme Court decisions provides a foundation, but ongoing judicial development will be necessary to address new forms of testamentary disputes.

Technological Advances and Future Developments

The increasing digitization of government services, including registration processes, may further enhance the reliability and accessibility of registered wills. Electronic systems can incorporate additional verification mechanisms, maintain more comprehensive records, and reduce the possibilities for manipulation or fraud.

Future developments may include enhanced identity verification procedures, digital signature requirements, and blockchain-based record keeping that could provide even stronger foundations for legal presumptions. These technological advances could further strengthen the rationale for preferring registered wills in testamentary disputes.

The integration of artificial intelligence and automated analysis tools in legal practice may also influence how will validity is assessed and challenged. These developments will require ongoing attention from courts and practitioners to ensure that legal frameworks remain current and effective.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s clarification in Metpalli Lasum Bai regarding registered wills represents a significant development in Indian testamentary law. By affirming the validity of registered wills and establishing that they carry a presumption of due execution and genuineness, with the burden of proof shifting to challengers, the Court has created a framework that facilitates legitimate succession while maintaining appropriate protections against fraud [1].

This legal evolution reflects a mature approach to balancing the competing interests present in testamentary disputes. The registration process provides meaningful safeguards that justify legal presumptions, while the rebuttable nature of these presumptions ensures that genuine cases of invalidity can still be addressed through appropriate evidence.

Legal practitioners, families, and individuals involved in estate planning should recognize the enhanced value of will registration under the current legal framework. The practical benefits, combined with the favorable legal presumptions, make registration an essential component of effective succession planning.

The broader implications of this development extend beyond individual cases to influence the entire landscape of succession law in India. By providing greater certainty and reducing litigation risks, the Supreme Court’s approach supports more efficient resolution of testamentary disputes and encourages greater reliance on formal legal instruments for wealth transfer.

Future developments in this area will likely focus on maintaining the appropriate balance between presumptions favoring registered wills and protection against sophisticated forms of testamentary fraud. The foundation established by recent jurisprudence provides a stable platform for ongoing legal development while serving the practical needs of India’s evolving society and economy.

References

[1] Metpalli Lasum Bai (since dead) & Others v. Metpalli Muthaih (dead) by Legal Heirs, 2025 INSC 879, https://www.scobserver.in/supreme-court-observer-law-reports-scolr/registered-will-presumed-genuine/

[2] The Registration Act, 1908, Section 35

[3] The Indian Succession Act, 1925, Section 63.

[4] Leela v. Muruganantham, 2025 INSC 10, https://www.livelaw.in/supreme-court/will-cant-be-presumed-to-be-valid-merely-because-it-is-registered-supreme-court-239579

[5] H. Venkatachala Iyengar v. B.N. Thimmajamma & Others, AIR 1959 SC 443, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/22929/

[6] Supreme Court Observer, “Registered Will Presumed Genuine,” July 28, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/supreme-court-observer-law-reports-scolr/registered-will-presumed-genuine/

[7] LiveLaw, “Registered Will Carries Presumption Of Genuineness,” July 22, 2025, https://www.livelaw.in/supreme-court/registered-will-carries-presumption-of-genuineness-burden-of-proof-on-party-disputing-its-validity-supreme-court-298355

[8] Legal Bites, “Can a Registered Will Be Presumed Genuine Without Additional Proof?” July 24, 2025, https://www.legalbites.in/bharatiya-Sakshya-adhiniyam/can-a-registered-will-be-presumed-genuine-without-additional-proof-1165192

[9] Indian Law Live, “Presumptions on Registered Documents,” April 5, 2025, https://indianlawlive.net/2021/10/08/presumptions-on-registered-documents-collateral-purpose/

Authorized and Published by Vishal Davda

Delhi High Court Strengthens Evidence Standards in Tax Prosecution: Critical Analysis of Foreign Banking Data Authentication Requirements

Introduction

In a landmark ruling that significantly strengthens evidentiary standards for tax prosecution cases involving foreign banking data, the Delhi High Court has established crucial precedents regarding the authentication requirements for international financial information used in criminal tax proceedings. The court’s decision in the case of Anurag Dalmia v. Income Tax Department marks a watershed moment in determining the admissibility of foreign documents obtained under Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements (DTAA) for initiating criminal prosecutions under the Income Tax Act, 1961[1]. This judicial pronouncement addresses the growing concern about the misuse of unverified international financial information in tax enforcement actions and establishes stringent authentication standards that tax authorities must meet before pursuing criminal charges based on foreign banking data. The ruling has far-reaching implications for taxpayers facing prosecution and sets new benchmarks for evidence standards in tax prosecution, ensuring that only verified and reliable information forms the basis of criminal proceedings.

Background of the Case and Legal Framework

The case originated from criminal complaints filed against Anurag Dalmia under Sections 276C(1)(i), 276D, and 277(1) of the Income Tax Act, 1961, based on alleged undisclosed foreign bank accounts in HSBC Bank, Switzerland. The foundation of these complaints rested entirely on information received from the French government under the India-France DTAA, without any corroborative evidence from Swiss authorities or independent verification[2].

The petitioner had originally filed income tax returns for assessment years 2006-07 and 2007-08, which were processed by the department with refunds issued. Subsequently, in 2011, the Income Tax Department received information from French authorities suggesting the petitioner’s connection to Swiss bank accounts. This led to search operations at the petitioner’s premises in 2012, which yielded no incriminating material.

The Income Tax Appellate Tribunal (ITAT) had earlier set aside the assessment order dated 23 March 2015 in its order dated 15 February 2018, finding no justification for reopening the assessment or making additions to the petitioner’s income. Despite this, the department continued with criminal prosecution, leading to the present proceedings before the Delhi High Court.

Analysis of Relevant Legal Provisions

Section 276C of the Income Tax Act, 1961

Section 276C(1)(i) of the Income Tax Act, 1961, forms the cornerstone of tax prosecution in cases involving willful tax evasion. The provision states: “If a person willfully attempts in any manner whatsoever to evade any tax, penalty or interest chargeable or imposable on him under this Act, he shall be punishable with rigorous imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than six months but which may extend to seven years and with fine”[3].

The critical element in this provision is the requirement to prove “willful attempt to evade tax,” which necessitates concrete evidence of deliberate concealment or misrepresentation. The Delhi High Court’s ruling emphasizes that mere possession of unverified documents suggesting foreign bank accounts, without authentication or corroborative evidence, cannot satisfy the stringent burden of proof required under this section.

Section 276D – Failure to Answer Questions or Sign Statements

Section 276D addresses situations where taxpayers fail to comply with procedural requirements during investigations. However, the court clarified that the petitioner’s refusal to sign a consent waiver form for accessing Swiss bank account details, while resulting in penalties under Section 271(1)(b), could not alone justify criminal prosecution under this provision[4].

Section 277 – False Statements in Verification

Section 277(1) penalizes false statements made in returns or documents submitted to tax authorities. The provision requires proof that the taxpayer made materially false statements knowing them to be false. In the absence of verified evidence establishing the existence of undisclosed accounts, no case under this section could be sustained.

Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements and Information Exchange

Legal Framework of DTAA

Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements represent bilateral treaties between countries designed to prevent the double taxation of income and facilitate the exchange of tax-related information. India has entered into comprehensive DTAAs with over 90 countries, including France, to promote bilateral trade and investment while ensuring proper tax compliance[5].

The India-France DTAA, like most modern tax treaties, contains provisions for the exchange of information between tax authorities of both countries. Article 27 of the India-France DTAA specifically deals with the exchange of information and stipulates that contracting states shall exchange such information as is foreseeably relevant to carrying out the provisions of the agreement or the domestic laws concerning taxes covered by the agreement.

Authentication Requirements for DTAA Information

The Delhi High Court’s ruling establishes that information received under DTAA provisions must meet certain authentication standards before being used as the basis for criminal prosecution. The court observed that documents received from France regarding Swiss bank accounts lacked proper authentication from Swiss authorities, making them insufficient for sustaining criminal charges.

This requirement aligns with fundamental principles of evidence law, which demand that documents produced in court proceedings must be properly authenticated to establish their genuineness and reliability. The mere receipt of information from a foreign tax authority under DTAA provisions does not automatically confer admissibility or reliability upon such information for criminal prosecution purposes.

Evidence Standards in Tax Prosecution Cases

Burden of Proof in Criminal Tax Proceedings

Tax prosecution cases under the Income Tax Act require the prosecution to establish guilt beyond reasonable doubt, similar to other criminal proceedings. The burden of proof is significantly higher than in civil tax proceedings, where the standard is based on the preponderance of probabilities. The Delhi High Court’s ruling reinforces this principle by holding that unverified foreign documents cannot meet the stringent evidence standards required for criminal conviction[6].

The court emphasized that the foundation of criminal prosecution cannot rest entirely on unverified documents that lack authentication or corroborative evidence. This principle ensures that taxpayers are protected from prosecutions based on unreliable or incomplete information, maintaining the integrity of the criminal justice system in tax matters.

Corroborative Evidence Requirements

The judgment establishes that information received under DTAA provisions must be supported by corroborative evidence to sustain criminal prosecution. In the instant case, the complete absence of incriminating material during search operations, combined with the lack of authentication from Swiss authorities, created an evidential void that could not support criminal charges.

This requirement for corroborative evidence serves as a crucial safeguard against prosecutions based solely on foreign intelligence or unverified information. It ensures that tax authorities must conduct thorough investigations and gather reliable evidence before initiating criminal proceedings that can have serious consequences for taxpayers.

Implications for Tax Enforcement and Compliance

Impact on Search and Seizure Operations

The ruling has significant implications for search and seizure operations conducted by tax authorities based on foreign intelligence. Tax departments must now ensure that such operations are supported by reliable, authenticated information rather than mere intelligence reports from foreign sources. The failure to discover incriminating material during searches based on unverified foreign information may serve as evidence against the reliability of such intelligence[7].

Procedural Safeguards for Taxpayers

The judgment strengthens procedural safeguards for taxpayers by establishing that the refusal to cooperate in providing access to foreign bank account information, while potentially attracting penalties, cannot alone justify criminal prosecution. This protection is particularly important given the complex legal and practical issues involved in accessing information from foreign financial institutions.

The court’s recognition that penalties under Section 271(1)(b) for non-cooperation cannot be converted into grounds for criminal prosecution maintains the proportionality principle in tax enforcement. This ensures that civil non-compliance issues are addressed through appropriate civil remedies rather than being escalated to criminal proceedings without sufficient evidence.

International Best Practices and Comparative Analysis

Global Standards for Information Authentication

International best practices in tax information exchange emphasize the importance of proper authentication and verification procedures. The OECD Model Tax Convention and its commentary provide guidelines for ensuring the reliability of exchanged information, including requirements for authentication and verification before such information is used in enforcement actions.

The Delhi High Court’s ruling aligns with these international standards by requiring proper authentication of foreign financial information before its use in criminal prosecutions. This approach ensures that India’s tax enforcement practices meet global standards of fairness and reliability in international tax cooperation.

Comparative Jurisprudence

Similar issues have been addressed by courts in other jurisdictions, with most adopting stringent standards for prosecutions based on foreign intelligence. The principle that unverified foreign information alone cannot sustain criminal prosecution reflects a universal commitment to maintaining high evidence standards in tax prosecution.

Regulatory Framework and Compliance Requirements

Income Tax Rules and Authentication Procedures

The Income Tax Rules, 1962, contain specific provisions regarding the authentication of documents and notices. Rule 127A of the Income Tax Rules deals with the authentication requirements for various tax documents, emphasizing the importance of proper authentication in tax proceedings[8].

While this rule primarily addresses domestic documents, the principles underlying authentication requirements extend to foreign documents used in tax proceedings. The Delhi High Court’s ruling reinforces these principles by requiring proper authentication of foreign financial information before its use in criminal prosecutions.

Black Money (Undisclosed Foreign Income and Assets) and Imposition of Tax Act, 2015

The Black Money Act, 2015, provides a specific framework for dealing with undisclosed foreign income and assets. Recent amendments to the CBDT instructions under this Act have raised the threshold for prosecution in cases involving foreign bank accounts from ₹5 lakh to ₹20 lakh, reflecting a more nuanced approach to enforcement[9].

This legislative development, combined with the Delhi High Court’s ruling on evidence standards in tax prosecution, indicates a trend toward more balanced and proportionate tax enforcement in cases involving foreign assets. The emphasis on proper evidence and authentication requirements ensures that the enhanced penalties under the Black Money Act are applied only in cases with reliable evidence.

Practical Implications for Tax Practitioners and Taxpayers

Advisory Considerations for Tax Practitioners

Tax practitioners advising clients in matters involving foreign assets must now consider the enhanced evidence standards established by the Delhi High Court ruling. This includes advising clients about their rights regarding authentication of foreign information and the limitations of prosecution based on unverified documents.

The ruling provides strong grounds for challenging prosecutions based solely on unverified foreign information, offering tax practitioners powerful arguments for defending clients facing such charges. However, practitioners must also advise clients about the importance of maintaining proper documentation and compliance with reporting requirements to avoid enforcement actions.

Compliance Strategies for Taxpayers

Taxpayers with foreign assets should ensure full compliance with reporting requirements under various provisions of the Income Tax Act and the Black Money Act. While the Delhi High Court ruling provides protection against prosecutions based on unverified information, it does not eliminate the obligation to disclose foreign assets and income properly.

The ruling emphasizes the importance of maintaining proper documentation and being transparent in dealings with tax authorities. Taxpayers should also be aware of their rights regarding the authentication of foreign information used against them in enforcement proceedings.

Future Outlook and Legal Developments

Expected Impact on Tax Jurisprudence

The Delhi High Court’s ruling is likely to influence future decisions in similar cases, establishing a precedent for stringent evidence standards in tax prosecution cases involving foreign information. This precedent may lead to the dismissal of prosecutions based on inadequate evidence and encourage tax authorities to strengthen their investigation procedures.

The ruling may also prompt legislative and regulatory reforms to establish clearer guidelines for the authentication and use of foreign information in tax enforcement. Such reforms could include specific procedures for verifying foreign intelligence and establishing minimum evidence standards for prosecution.

Implications for International Tax Cooperation

While strengthening evidence standards in tax prosecution, the ruling does not undermine the importance of international tax cooperation through information exchange agreements. Rather, it encourages more rigorous verification procedures that ultimately enhance the reliability and effectiveness of such cooperation.

The ruling may lead to the development of enhanced authentication procedures in future DTAA negotiations and amendments, ensuring that information exchange serves its intended purpose while maintaining appropriate safeguards for taxpayers.

Conclusion

The Delhi High Court’s landmark ruling in the Anurag Dalmia case represents a significant advancement in protecting taxpayer rights while maintaining the integrity of tax enforcement proceedings. By establishing stringent authentication requirements for foreign financial information used in criminal prosecutions, the court has created essential safeguards against prosecutions based on unreliable or unverified evidence.

The ruling serves multiple important purposes: it protects taxpayers from unfair prosecution based on unverified foreign intelligence, maintains high evidence standards in criminal tax proceedings, and encourages tax authorities to conduct thorough investigations before initiating prosecution. These developments align with constitutional principles of fairness and due process while supporting legitimate tax enforcement objectives.

For tax practitioners and taxpayers, the ruling provides important guidance on rights and obligations in matters involving foreign assets. It emphasizes the importance of proper authentication procedures while recognizing the limitations of prosecution based on inadequate evidence. As international tax cooperation continues to evolve, this ruling will likely serve as an important benchmark for balancing enforcement objectives with taxpayer protection and maintaining robust evidence standards in tax prosecution.

The decision ultimately strengthens the tax system by ensuring that enforcement actions are based on reliable evidence and proper procedures. This approach enhances public confidence in tax administration while maintaining India’s commitment to international cooperation in tax matters. As the tax landscape continues to evolve with increasing global integration, such judicial guidance becomes increasingly valuable in maintaining the delicate balance between effective enforcement and fairness to taxpayers.

References

[1] Anurag Dalmia v. Income Tax Department, Delhi High Court, Criminal Miscellaneous Petition, 2025. Available at: https://www.taxscan.in/top-stories/unverified-documents-from-france-about-foreign-bank-account-cannot-support-income-tax-prosecution-without-swiss-authentication-delhi-hc-1431077

[2] “Unauthenticated Documents From Foreign Govt Regarding Swiss Bank Account Cannot Form Basis For Criminal Action: Delhi HC”, Live Law, July 2025. Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/high-court/delhi-high-court/unauthenticated-documents-from-foreign-govt-regarding-swiss-bank-account-of-assessee-cant-form-basis-for-criminal-action-delhi-hc-298485

[3] Income Tax Act, 1961, Section 276C. Available at: https://incometaxindia.gov.in

[4] Income Tax Act, 1961, Section 276D. Available at: https://incometaxindia.gov.in

[5] “International Taxation – Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements”, Income Tax Department. Available at: https://incometaxindia.gov.in/Pages/international-taxation/dtaa.aspx

[6] “Black Money – Foreign Bank Accounts & Criminal Prosecutions Under The Income Tax Act”, Mondaq, July 2016. Available at: https://www.mondaq.com/india/tax-authorities/511964/black-money–foreign-bank-accounts-criminal-prosecutions-under-the-indian-income-tax-act

[7] “Prosecution u/s 276C on information received under DTAA for third country”, ABC of Income Tax, August 2021. Available at: https://abcaus.in/income-tax/prosecution-u-s-276c-information-received-under-dtaa-third-country.html

[8] Income Tax Rules, 1962, Rule 127A.

[9] “CBDT Amends Instructions on Prosecution under Black Money Act, 2015”, A2Z Taxcorp LLP, August 2025. Available at: https://a2ztaxcorp.net/cbdt-amends-instructions-on-prosecution-under-black-money-undisclosed-foreign-income-and-assets-and-imposition-of-tax-act-2015/

Legislative Roundup: Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar’s Resignation and Key Labor, Environment, and Technology Law Updates

Introduction

The year 2025 has marked a significant period of legislative transformation in India, characterized by unprecedented constitutional developments and sweeping regulatory reforms across multiple sectors. The most notable event was the vice president jagdeep dhankhar’s resignation on July 21, 2025, which created ripple effects across India’s constitutional framework. Simultaneously, the country witnessed substantial legislative changes in labor laws, environmental regulations, and technology governance that will reshape India’s legal landscape for years to come.

This legislative roundup examines the constitutional implications of the vice president jagdeep dhankhar’s resignation, analyzes the implementation of new labor codes, reviews environmental law updates, and explores emerging technology regulations. These developments represent a paradigm shift in how India approaches governance, worker protection, environmental stewardship, and digital transformation.

Constitutional Framework: Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar’s Historic Resignation

Constitutional Provisions Governing Resignation

Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar’s resignation on July 21, 2025, invoked Article 67(a) of the Indian Constitution, which states that “the Vice-President may, by writing under his hand addressed to the President, resign his office” [1]. This constitutional provision provides the mechanism through which the second-highest constitutional office in India can be vacated voluntarily. The resignation took effect immediately upon submission to President Droupadi Murmu, demonstrating the constitutional principle of immediate transfer of authority in high offices.

The constitutional framework surrounding the Vice President’s office is established under Part V of the Constitution, specifically Articles 63 to 71. Article 63 establishes that “there shall be a Vice-President of India,” while Article 64 designates the Vice President as the ex-officio Chairman of the Rajya Sabha. The resignation under Article 67(a) represents only the third instance in India’s constitutional history where a Vice President has resigned mid-term, following V.V. Giri in 1969 and Mohammad Hidayatullah in 1979.

Legal Implications and Precedential Value

Vice president jagdeep dhankhar’s resignation citing health concerns establishes an important precedent regarding the voluntary relinquishment of high constitutional offices. The constitutional principle underlying such resignations rests on the doctrine of public service and the recognition that effective discharge of constitutional duties requires physical and mental capability. This precedent reinforces the constitutional value that public office is held in trust for the people, and occupants must prioritize public interest over personal ambition.

The immediate effect of the resignation triggered the constitutional mechanism under Article 67(b), which provides for succession arrangements. The Deputy Chairman of the Rajya Sabha assumes the functions of the Chairman until a new Vice President is elected. The Election Commission of India, acting under the Conduct of Election Rules, 1961, and the Presidential and Vice-Presidential Elections Act, 1952, announced elections for September 9, 2025 [2].

Electoral Process and Constitutional Requirements

The election of a new Vice President follows the procedure outlined in Article 66 of the Constitution, which mandates election by an electoral college consisting of members of both Houses of Parliament. The election process is governed by the system of proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote, ensuring broader representation across party lines. This electoral mechanism reflects the constitutional design of creating consensus-based leadership for the second-highest office in the country.

Labor Law Transformation: Implementation of New Labor Codes

The Four Pillars of Labor Reform

India’s labor law landscape underwent revolutionary changes with the implementation of four new labor codes that replaced 29 existing central labor laws [3]. These codes represent the most ambitious labor law reform since independence, addressing wages, social security, occupational safety and health, and industrial relations. The Wage Code, 2019; the Industrial Relations Code, 2020; the Code on Social Security, 2020; and the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code, 2020 collectively establish a new paradigm for worker protection and employer obligations.

The Code on Wages, 2019, universalizes the concept of minimum wage across all sectors and establishes a statutory floor wage below which no minimum wage can be fixed. Section 6 of the Code mandates that “the Central Government shall fix a floor wage taking into account the living standard of workers” [4]. This provision ensures that minimum wage fixation considers regional economic conditions while maintaining national standards for worker welfare.

Minimum Wage Restructuring and Implementation

The new wage structure under the updated codes establishes differentiated minimum wages based on skill levels. Unskilled workers are entitled to a daily minimum wage of ₹783, semi-skilled workers receive ₹868, and highly skilled workers earn ₹1,035 per day [5]. This skill-based differentiation represents a departure from the previous uniform approach and acknowledges the economic value of different skill sets in the modern economy.

The implementation mechanism involves state governments fixing minimum wages within their jurisdictions while adhering to the central floor wage. Section 9 of the Code on Wages requires that “the appropriate government shall review and revise the minimum rates of wages at intervals not exceeding five years.” This provision ensures regular adjustment of wages to reflect economic changes and inflation patterns, protecting workers from erosion of purchasing power.

Social Security Expansion and Coverage

The Code on Social Security, 2020, extends social security coverage to previously excluded categories of workers, including gig workers, platform workers, and fixed-term employees. Section 2(60) defines “organised worker” broadly to include “an employee in the organised sector and includes a fixed term employee” [6]. This expansion addresses the changing nature of employment relationships in the digital economy and provides security to millions of previously unprotected workers.

The Code establishes various social security schemes including the Employees’ Provident Fund, Employees’ State Insurance, Employees’ Compensation, Employment Injury Benefit Scheme, and Maternity Benefits. Chapter VII of the Code specifically addresses “Social Security for Gig Workers and Platform Workers,” recognizing the emergence of new employment categories in the digital economy.

Environmental Law Updates and Regulatory Framework

Climate Change Mitigation and Legal Framework

India’s environmental law framework has evolved significantly to address climate change challenges and international commitments under the Paris Agreement. The Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, continues to serve as the primary legislative framework for environmental protection, but recent amendments and notifications have strengthened implementation mechanisms and expanded regulatory scope [7].

The National Green Tribunal (NGT), established under the National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, has played a crucial role in environmental jurisprudence. Section 14 of the NGT Act provides that “the Tribunal shall have the jurisdiction over all civil cases where a substantial question relating to environment (including air and water pollution) is involved” [8]. Recent judgments by the NGT have established important precedents regarding environmental clearances, pollution control, and restoration obligations.

Forest Conservation and Biodiversity Protection

The Forest Conservation Act, 1980, underwent significant amendments to strengthen forest protection mechanisms while facilitating legitimate developmental activities. Section 2 of the Act prohibits “de-reservation of forests or use of forest land for non-forest purpose” except with central government approval. Recent notifications have streamlined the forest clearance process while maintaining stringent environmental safeguards.

The Biological Diversity Act, 2002, governs access to biological resources and associated traditional knowledge. Section 3 of the Act regulates “access to biological diversity by foreign individuals, institutions or companies” and requires prior approval from the National Biodiversity Authority. Recent amendments have strengthened penalty provisions and expanded the scope of regulated activities to address biopiracy concerns.

Pollution Control and Regulatory Enforcement

The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, and the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981, form the backbone of India’s pollution control framework. These Acts establish State Pollution Control Boards and the Central Pollution Control Board with powers to regulate industrial emissions and effluents. Section 25 of the Water Act requires “no person shall, without the previous consent of the State Board, establish or take any steps to establish any industry, operation or process which is likely to discharge sewage or trade effluent” [9].

Recent amendments have strengthened penalty provisions and introduced environmental compensation mechanisms. The concept of “polluter pays” has been reinforced through judicial interpretation and regulatory guidance, making polluting industries liable for restoration costs and environmental damage.

Technology Law and Digital Governance Framework

Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, represents India’s primary data protection legislation, establishing rights for data principals and obligations for data fiduciaries. Section 5 of the Act provides that “personal data shall be processed lawfully, fairly and transparently” [10]. The Act introduces concepts of data localization, cross-border data transfer restrictions, and significant penalties for non-compliance.

The Act establishes the Data Protection Board of India with powers to investigate violations, impose penalties, and issue binding directions. Section 18 empowers the Board to “inquire into any complaint made to it or, on its own motion, inquire into any breach of the provisions of this Act.” This enforcement mechanism provides teeth to data protection laws and ensures meaningful compliance by digital platforms and service providers.

Information Technology Act Amendments

The Information Technology Act, 2000, continues to govern cyberspace regulation, but recent amendments have expanded its scope to address emerging digital challenges. Section 43A of the IT Act mandates that “where a body corporate, possessing, dealing or handling any sensitive personal data or information in a computer resource which it owns, controls or operates, is negligent in implementing and maintaining reasonable security practices and procedures” resulting in wrongful loss, such body corporate shall be liable to pay damages [11].

Recent Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, have imposed additional obligations on social media intermediaries and digital news publishers. These rules require intermediaries to establish grievance redressal mechanisms, trace message origins when legally required, and comply with government takedown orders within specified timeframes.

Industrial Relations and Collective Bargaining

Modernized Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

The Industrial Relations Code, 2020, modernizes India’s industrial relations framework by consolidating three existing laws and introducing contemporary dispute resolution mechanisms. Section 55 of the Code establishes “Industrial Relations Committees” at establishment level to “promote measures for securing and preserving amity and good relations between the employer and workmen” [12].

The Code introduces the concept of “negotiating unions” and “negotiating councils” to formalize collective bargaining processes. Chapter V of the Code specifically deals with “Recognition of Trade Unions and Negotiating Union or Negotiating Council,” providing a structured approach to worker representation and collective negotiations.

Strike and Lockout Provisions

The Code maintains restrictions on strikes and lockouts while providing clearer procedures for legal industrial action. Section 61 prohibits strikes and lockouts in “public utility services” during the pendency of proceedings before any labour court, tribunal, or arbitrator. This provision balances the fundamental right to collective bargaining with the need to maintain essential services.

The definition of “public utility service” under Section 2(53) includes railways, air transport services, postal, telegraph and telephone services, and generation, production and supply of electricity. This expanded definition recognizes the critical nature of infrastructure services in the modern economy while preserving worker rights within defined parameters.

Occupational Safety and Health Standards

Enhanced Safety Framework

The Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code, 2020, establishes modern safety standards applicable to all sectors of the economy. Section 25 mandates that “every employer shall ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the safety, health and welfare at work of all workers while they are at work” [13]. This provision establishes the fundamental employer obligation for workplace safety across all industries and employment categories.

The Code introduces risk-based enforcement and self-certification mechanisms for low-risk industries while maintaining strict oversight for high-risk sectors. Chapter III specifically addresses “Safety and Health,” requiring employers to conduct risk assessments, implement safety management systems, and provide safety training to workers.

Working Conditions and Welfare Provisions

The Code modernizes working time regulations and introduces flexibility in work arrangements while protecting worker welfare. Section 54 limits working hours to “not more than eight hours in a day and forty-eight hours in a week” while allowing flexible scheduling arrangements subject to worker consent and safety considerations.

Welfare provisions under Chapter V include requirements for drinking water, washing facilities, first aid, canteens, and rest rooms. These provisions ensure basic amenities for workers while allowing employers flexibility in implementation based on establishment size and nature of operations.

Regulatory Compliance and Enforcement Mechanisms

Unified Compliance Framework

The new labor codes introduce a unified compliance and enforcement framework designed to reduce regulatory burden while strengthening worker protection. The concept of “Inspector-cum-Facilitator” under Section 51 of the Industrial Relations Code transforms the traditional enforcement approach from punitive to facilitative, encouraging compliance through guidance rather than merely penalizing violations.

Digital platforms for registration, returns, and compliance management streamline administrative processes and reduce bureaucratic delays. The introduction of composite registration and unified returns reduces paperwork and compliance costs for employers while maintaining regulatory oversight.

Penalty Structure and Enforcement

Enhanced penalty provisions across all codes ensure deterrent effect against violations while providing proportionate sanctions. The Industrial Relations Code prescribes imprisonment up to one year or fine up to ₹1 lakh or both for violations of strike and lockout provisions. This graduated penalty structure balances the need for compliance with the principle of proportionality in punishment.

Conclusion

The legislative developments of 2025, marked by Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar’s resignation and the implementation of new labor codes, represent a watershed moment in India’s legal evolution. These changes reflect the country’s commitment to constitutional governance, worker protection, environmental stewardship, and digital transformation. The constitutional precedent established by the Vice Presidential resignation reinforces democratic values and the principle that public office is held in trust for the people.

The new labor codes promise to modernize India’s industrial relations framework while protecting worker rights and promoting economic growth. Environmental law updates demonstrate India’s commitment to sustainable development and climate change mitigation. Technology regulations address the challenges of digital transformation while protecting citizen privacy and data security.

These legislative changes require careful implementation and continuous monitoring to achieve their intended objectives. The success of these reforms will depend on effective enforcement mechanisms, stakeholder cooperation, and adaptive governance approaches that respond to emerging challenges while maintaining the rule of law and constitutional values.

References

[1] Constitution of India, Article 67(a). Available at: https://legislative.gov.in/constitution-of-india

[2] Election Commission of India. (2025). Notification for Vice President Election.

[3] Ministry of Labour & Employment. (2025). Labour Law Reforms. Government of India. Available at: https://labour.gov.in/labour-law-reforms

[4] The Code on Wages, 2019, Section 6.

[5] Sankhla & Co. (2025). India’s New Labour Laws 2025: Updates & Implementation Plan. Available at: https://sankhlaco.com/indias-labour-codes-set-to-be-implemented-in-stages-starting-in-2025-important-developments/

[6] The Code on Social Security, 2020, Section 2(60).

[7] Environment (Protection) Act, 1986.

[8] National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, Section 14.

[9] Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, Section 25.

Authorized and Published by Dhrutika Barad

Expanding the Horizons of Article 21: Supreme Court’s Landmark Recognition of Mental Health as a Fundamental Right to Life in Sukdeb Saha v. State of Andhra Pradesh

Introduction

In a groundbreaking judgment that will reshape the landscape of constitutional rights and mental health jurisprudence in India, the Supreme Court in Sukdeb Saha v. State of Andhra Pradesh delivered on July 25, 2025, has unequivocally declared that mental health constitutes an integral component of the fundamental right to life under Article 21 of the Constitution [1]. This landmark decision, rendered by a bench comprising Justice Vikram Nath and Justice Sandeep Mehta, emerged from the tragic circumstances surrounding the death of a 17-year-old NEET aspirant and has resulted in the establishment of comprehensive mental health guidelines for educational institutions across the country.

The judgment represents a significant evolution in the interpretation of Article 21, extending beyond the traditional understanding of the right to life to encompass psychological well-being and mental health protection. This judicial pronouncement comes at a critical juncture when India faces an alarming rise in student suicides, with the National Crime Records Bureau reporting 13,044 student suicides in 2022, representing a disturbing increase from 5,425 cases in 2001.

Constitutional Framework and the Evolution of Article 21

The Supreme Court’s recognition of mental health as a component of the right to life represents the natural progression of constitutional jurisprudence that has consistently expanded the scope of Article 21 beyond mere physical existence. Article 21 of the Indian Constitution states: “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law” [2]. However, judicial interpretation has transformed this seemingly narrow provision into a repository of various fundamental rights essential for human dignity.

The evolution began with the landmark judgment in Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978), where the Supreme Court held that the right to life includes the right to live with human dignity [3]. This interpretation was further expanded in Francis Coralie Mullin v. Administrator, Union Territory of Delhi (1981), which established that the right to life encompasses all aspects that make life meaningful, complete, and worth living [4].

The Sukdeb Saha judgment builds upon this foundation by explicitly acknowledging that mental health is central to the vision of life with dignity, autonomy, and well-being. The Court observed that mental health has been consistently recognized in precedents such as Shatrughan Chauhan v. Union of India (2014) and Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India (2018), which affirmed mental integrity, psychological autonomy, and freedom from degrading treatment as essential facets of human dignity under Article 21 [5].

The Tragic Circumstances: Facts of Sukdeb Saha Case

The case originated from the unfortunate death of a 17-year-old girl, referred to as Ms. X in the judgment, who was pursuing NEET coaching at Aakash Byju’s Institute in Vishakhapatnam. The student was residing at Sadhana Ladies Hostel when she allegedly fell from the third floor on July 14, 2023. The circumstances surrounding her death raised serious questions about the adequacy of investigation, medical care, and institutional responsibility.

The appellant, Ms. X’s father from West Bengal, challenged the perfunctory investigation conducted by local police authorities, who hastily concluded the case as suicide without proper investigation. The Supreme Court identified numerous inconsistencies in the investigation, including contradictory CCTV footage showing different clothing on the victim, failure to record the statement of the conscious victim, premature destruction of crucial forensic evidence, and suspicious circumstances surrounding medical treatment.

The Court observed that the original investigation suffered from “glaring inconsistencies” and “ineffectiveness of the local police officials,” necessitating transfer to the Central Bureau of Investigation for impartial inquiry [6]. However, the judgment’s significance transcends the individual case to address the broader crisis of student mental health in educational institutions.

Legislative and Regulatory Framework for Mental Health

The Supreme Court’s pronouncement aligns with and reinforces the existing legislative framework for mental health protection in India. The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017, serves as the primary legislation governing mental health rights and services in the country. Section 18 of the Act guarantees mental health services to all persons, while Section 115 explicitly decriminalizes attempted suicide, acknowledging the need for care and support rather than punishment [7].

The Act defines “mental healthcare” under Section 2(s) as “analysis and diagnosis of a person’s mental condition and treatment, care and rehabilitation for a mental illness or suspected mental illness.” More significantly, Section 21 of the Mental Healthcare Act establishes the right to access mental healthcare as a fundamental entitlement, stating that “every person shall have a right to access mental healthcare and treatment from mental health services run or funded by the appropriate Government.”

The Supreme Court in Sukdeb Saha emphasized that these legislative provisions, read with judicial precedents, reflect a broader constitutional vision that mandates a responsive legal framework to prevent self-harm and promote well-being, particularly among vulnerable populations such as students and youth. The judgment notes that despite these constitutional and legislative provisions, there remains “a legislative and regulatory vacuum in the country with respect to a unified, enforceable framework for suicide prevention of students in educational institutions.”

International Law Obligations and Comparative Analysis

The Supreme Court’s recognition of mental health rights finds strong support in India’s international law obligations. The judgment specifically references Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, to which India is a party, recognizing the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health [8].

The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, in General Comment No. 14, has affirmed that this right includes timely access to mental health services and prevention of mental illness, including suicide. The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006, recognizes mental health conditions within the scope of psychosocial disabilities and mandates accessible, non-discriminatory mental health care.

The World Health Organization’s Mental Health Action Plan identifies suicide prevention as a public health priority, calling upon states to reduce suicide mortality rates through national strategies, school-based interventions, and community support mechanisms. The Supreme Court observed that these evolving international norms reinforce the view that suicide prevention is not merely a policy objective but a binding obligation flowing from the right to life, health, and human dignity.

The Crisis of Student Suicides: Statistical Evidence and Systemic Failure

The Supreme Court’s judgment provides a comprehensive analysis of the student suicide crisis based on National Crime Records Bureau data. The statistics reveal a deeply disturbing trend, with India recording 1,70,924 suicide cases in 2022, of which 13,044 (7.6%) were student suicides. Significantly, 2,248 of these deaths were directly attributed to examination failure.

The judgment notes that student suicides have increased from 5,425 in 2001 to 13,044 in 2022, representing a more than doubling over two decades. In the decade beginning from 2012, male student suicides surged by 99% and female student suicides jumped by 92%. The Court emphasized that these figures represent “precious lives lost, young minds prematurely silenced by pressures they were unable to bear.”

The Supreme Court identified multiple contributing factors to student suicides, including low self-esteem, unrealistic academic expectations, impulsivity, social isolation, learning disabilities, and past trauma such as physical or sexual abuse. The judgment particularly highlighted suicides precipitated by sexual assault, harassment, ragging, bullying, or discrimination based on caste, gender, sexual orientation, or disability, noting that these remain “underreported and inadequately addressed.”

Fifteen Comprehensive Guidelines for Educational Institutions

The Supreme Court, exercising powers under Article 32 and treating the pronouncement as law declared under Article 141, issued fifteen comprehensive guidelines for all educational institutions across India. These guidelines represent the most detailed judicial framework for mental health protection in educational settings.

The guidelines mandate that all educational institutions adopt uniform mental health policies drawing from existing frameworks such as the UMMEED Draft Guidelines, MANODARPAN initiative, and National Suicide Prevention Strategy. Institutions with 100 or more students must appoint qualified mental health professionals, while smaller institutions must establish formal referral linkages.