Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

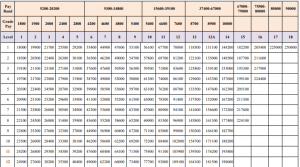

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

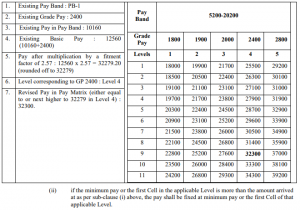

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

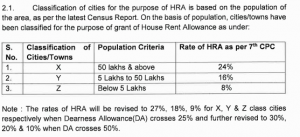

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

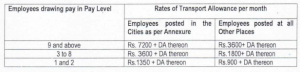

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Attorney-Client Privilege in India: Scope and Limitations for Corporate and Criminal Matters

Introduction to Attorney-Client Privilege in India

The relationship between a lawyer and client stands as one of the most sacred bonds in any legal system, built upon the foundation of trust, confidentiality, and professional duty. In India, this relationship finds its legal protection through the doctrine of attorney-client privilege, which ensures that communications between legal advisors and their clients remain confidential and protected from compelled disclosure in judicial proceedings. This privilege serves not merely as a procedural shield but as an essential pillar supporting the administration of justice itself, enabling clients to seek legal advice without fear that their candid disclosures might later be used against them.

The legal framework governing attorney-client privilege in India derives primarily from the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, which codifies the circumstances under which communications between lawyers and clients enjoy protection from disclosure. The privilege recognizes that effective legal representation requires complete honesty from clients, which can only be achieved when they trust that their communications will remain confidential. This principle applies equally whether the legal matter involves complex corporate transactions, criminal prosecutions, civil disputes, or regulatory investigations. The doctrine has evolved through statutory provisions and judicial interpretations to balance the competing interests of confidentiality and the pursuit of truth in legal proceedings [1].

Statutory Framework Under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872

Section 126: Protection of Professional Communications

Section 126 of the Indian Evidence Act forms the cornerstone of attorney-client privilege in India. This provision states that “No barrister, attorney, pleader or vakil shall at any time be permitted, unless with his client’s express consent, to disclose any communication made to him in the course and for the purpose of his employment as such barrister, pleader, attorney or vakil, by or on behalf of his client, or to state the contents or condition of any document with which he has become acquainted in the course and for the purpose of his professional employment, or to disclose any advice given by him to his client in the course and for the purpose of such employment.” The language of this section makes clear that the prohibition on disclosure operates at all times, not merely during the pendency of particular proceedings [2].

The protection afforded by Section 126 extends beyond mere oral communications to encompass documents, written advice, and any information that comes to the legal advisor’s knowledge during the professional relationship. The phrase “in the course and for the purpose of his employment” establishes two essential criteria that must be satisfied for the privilege to attach. First, the communication must occur during the existence of the professional relationship. Second, the communication must relate to legal advice or assistance being sought or provided. Casual conversations between a lawyer and client that have no connection to legal matters would not attract the privilege. Similarly, communications made before the professional relationship commences or after it has terminated may not receive protection, though courts have sometimes extended the privilege to pre-retainer consultations when they directly relate to the subsequent representation.

The statute explicitly requires the client’s express consent before a lawyer may disclose privileged communications. This requirement underscores that the privilege belongs to the client, not the lawyer. While the lawyer has a duty to maintain confidentiality and assert the privilege on behalf of the client, the client retains the ultimate authority to waive it. The express consent requirement means that implied consent or tacit approval generally will not suffice to authorize disclosure. Courts have interpreted this provision to mean that clients must affirmatively and knowingly waive the privilege, understanding the consequences of such waiver [3].

Section 127: Extension to Interpreters and Intermediaries

Section 127 extends the protections of Section 126 to interpreters and other persons who assist in facilitating communications between lawyers and clients. This provision recognizes the practical reality that modern legal practice often involves third parties who become privy to privileged communications by necessity. The section states that “Section 126 shall apply to interpreters, and to the clerks or servants of barristers, pleaders, attorneys and vakils.” By including these individuals within the scope of privilege, the law acknowledges that the purpose of protecting client confidences would be defeated if interpreters, translators, paralegals, legal assistants, or other support staff could be compelled to testify about matters they learned while assisting in the provision of legal services.

The rationale behind extending privilege to these intermediaries stems from the understanding that contemporary legal practice involves collaborative work environments where multiple individuals may have access to confidential information. In complex corporate matters, for instance, teams of lawyers and support staff may work on transactions or disputes, all of whom gain knowledge of privileged communications. Similarly, when clients speak languages other than those spoken by their lawyers, interpreters become essential conduits of communication. Without the protection offered by Section 127, the entire framework of attorney-client privilege could be circumvented simply by calling these intermediaries as witnesses.

Section 128: Privilege Not Waived by Volunteering Evidence

Section 128 addresses a specific scenario where a lawyer might voluntarily testify about certain matters but wishes to maintain privilege over other communications. The section provides that “If any party to a suit gives evidence therein at his own instance or otherwise, he shall not be deemed to have consented to such disclosure as is mentioned in section 126; and, if any party to a suit or proceeding calls any such barrister, pleader, attorney or vakil as a witness, he shall be deemed to have consented to such disclosure only if he questions such barrister, pleader, attorney or vakil on matters which, but for such question, he would not be at liberty to disclose.”

This provision establishes an important principle: merely giving evidence in a proceeding does not automatically waive attorney-client privilege over all communications with one’s lawyer. The waiver of privilege must be specific and intentional, not merely incidental to participation in litigation. For example, if a party testifies about the events leading to a dispute, this testimony does not open the door to questions about what the party told their lawyer about those events or what advice the lawyer gave. The privilege remains intact unless the party specifically introduces evidence about privileged communications or asks questions that can only be answered by disclosing such communications.

Section 129: Confidential Communications with Legal Advisers

Section 129 complements Section 126 by addressing the compellability of witnesses to disclose privileged communications. The section states “No one shall be compelled to disclose to the Court any confidential communication which has taken place between him and his legal professional adviser, unless he offers himself as a witness, in which case he may be compelled to disclose any such communications as may appear to the Court necessary to be known in order to explain any evidence which he has given, but no others.” This provision establishes that while privilege generally protects confidential communications from forced disclosure, a party who chooses to testify may be required to disclose communications necessary to explain their testimony [4].

The qualification contained in Section 129 reflects a balance between protecting privilege and preventing its misuse as a sword rather than a shield. If a party could testify selectively about favorable matters while using privilege to block examination on related privileged communications, it would create an unfair advantage and impede the search for truth. Therefore, when a party voluntarily takes the witness stand, they may be compelled to disclose privileged communications to the extent necessary to provide context and completeness to their testimony. However, this waiver remains limited in scope—the court may only require disclosure of communications directly relevant to explaining the evidence given, not all privileged communications generally.

Application of Attorney-Client Privilege in Corporate Matters

In-House Counsel and Corporate Legal Departments

The application of attorney-client privilege in the corporate context presents unique challenges that differ substantially from individual client representations. Corporations, as artificial legal persons, must necessarily act through human agents—directors, officers, employees, and other representatives. When in-house counsel or corporate legal departments provide advice to these individuals acting in their corporate capacity, questions arise about who constitutes the client for privilege purposes and what communications qualify for protection. Courts in India have generally recognized that corporations can claim attorney-client privilege for communications between their legal advisors and corporate representatives, provided these communications relate to seeking or providing legal advice in connection with corporate matters [5].

The determination of which corporate employees’ communications with counsel attract privilege has been subject to judicial scrutiny. Not every employee who communicates with corporate counsel can claim privilege for those communications. Generally, privilege extends to communications between counsel and employees who have authority to act on behalf of the corporation in the matter at hand or whose responsibilities place them in a position where their communications with counsel are necessary for the lawyer to provide effective legal advice to the corporation. This includes senior management, officers, directors, and employees specifically tasked with handling the legal issues in question. However, communications with employees who merely possess relevant information but lack decision-making authority may not always receive protection, particularly if those communications involve investigation of facts rather than provision of legal advice.

In-house counsel face a particular challenge in establishing privilege because they serve dual roles within corporations—providing legal advice while also participating in business decision-making and operational matters. Indian courts have recognized that not all communications involving in-house lawyers qualify for privilege protection. To attract privilege, the communication must be primarily for the purpose of seeking or providing legal advice, not business advice or operational guidance. When in-house counsel attend meetings or participate in discussions wearing their “business hat” rather than providing legal counsel, those communications may not receive privilege protection. Corporations must therefore carefully document the nature and purpose of communications with in-house counsel to preserve claims of privilege.

Corporate Investigations and Regulatory Matters

Corporate investigations, whether conducted internally in response to potential misconduct or initiated by regulatory authorities, raise complex privilege questions. When a corporation engages lawyers to investigate allegations of wrongdoing by employees or to assess compliance with legal requirements, communications during these investigations may attract privilege if properly structured. The key consideration is whether the investigation is conducted for the purpose of obtaining legal advice or in anticipation of litigation, as opposed to a purely business or operational assessment. Indian courts have not always been consistent in their treatment of investigative privilege, making it crucial for corporations to establish clear documentation of the legal purpose underlying investigations.

The relationship between corporate privilege and regulatory investigations has been the subject of considerable debate. When regulatory authorities such as the Securities and Exchange Board of India, the Reserve Bank of India, or the Competition Commission of India conduct investigations, they often seek access to legal advice and communications that corporations claim are privileged. While Indian law recognizes attorney-client privilege as a fundamental principle, regulatory statutes sometimes contain provisions requiring disclosure of information that may override privilege claims in specific contexts. Corporations facing regulatory investigations must carefully navigate these competing obligations, asserting privilege where appropriate while recognizing the limits of such protection in the face of statutory disclosure requirements [6].

Cross-Border Transactions and Foreign Legal Advice

The globalization of commerce has created situations where Indian corporations seek legal advice from foreign counsel regarding transactions or disputes with international dimensions. Questions arise about whether communications with foreign lawyers receive the same privilege protection under Indian law as communications with Indian advocates. The Indian Evidence Act does not explicitly address privilege for foreign legal consultants, though courts have generally extended privilege to communications with foreign lawyers when those communications concern legal advice related to matters that may come before Indian courts. However, the scope and application of such privilege can be uncertain, particularly when foreign lawyers are not qualified to practice in India or when the legal advice concerns foreign law rather than Indian law.

Indian corporations engaging in cross-border mergers, acquisitions, joint ventures, or financing transactions routinely obtain legal advice from counsel in multiple jurisdictions. To maintain privilege over these communications, corporations should ensure that foreign lawyers are engaged for the purpose of providing legal advice, not merely business consulting. Additionally, when foreign legal advice is communicated to the corporation through Indian counsel or when Indian lawyers coordinate with foreign counsel, the communications may receive stronger privilege protection than direct communications between foreign lawyers and corporate representatives. Careful attention to the structure of these advisory relationships can help preserve privilege claims across jurisdictions.

Application in Criminal Matters

Accused Persons and Defense Counsel

In criminal proceedings, the attorney-client privilege in India takes on heightened significance because the consequences extend beyond monetary damages to potentially include loss of liberty or even life. When an accused person consults with defense counsel, those communications receive robust protection under Sections 126 and 129 of the Evidence Act. This protection is essential to ensuring that accused persons can make a full and frank disclosure to their lawyers without fear that their admissions or explanations will be used against them. Without such protection, the constitutional guarantee of effective legal assistance would be severely undermined, as accused persons might withhold crucial information from their own lawyers out of fear of self-incrimination [7].

The privilege in criminal matters extends to communications between the accused and counsel at all stages of the proceedings, from initial consultation through investigation, trial, and appeals. It covers admissions of guilt, discussions of defense strategy, explanations of incriminating evidence, and all other communications relating to the representation. Notably, the privilege protects these communications even if they reveal criminal conduct, subject to certain exceptions discussed below. The lawyer has a professional duty to maintain confidentiality and cannot voluntarily disclose privileged communications without the client’s express consent, even after the conclusion of the criminal proceedings.

Limitations: Crime-Fraud Exception

While attorney-client privilege provides broad protection, it is not absolute. A critical limitation exists when legal advice is sought not for lawful purposes but to facilitate ongoing or future criminal conduct or fraud. Section 126 of the Evidence Act contains an explanation stating “Nothing in this section shall protect from disclosure any such communication made in furtherance of any illegal purpose or any fact observed by any barrister, pleader, attorney or vakil, in the course of his employment as such, showing that any crime or fraud has been committed since the commencement of his employment.” This crime-fraud exception represents a fundamental limitation on privilege because the law does not extend its protection to facilitate criminality.

The crime-fraud exception applies when a client consults a lawyer for advice on how to commit a crime or fraud or when the client uses the lawyer’s services to further illegal objectives. However, the exception does not apply merely because a client admits to past criminal conduct while seeking legal advice. The distinction is crucial: if a client confesses to a completed crime while seeking legal representation, that admission remains privileged. But if the client seeks advice on how to commit a future crime or use legal services to perpetrate ongoing fraud, those communications fall outside privilege protection. Indian courts have emphasized that the party seeking to invoke the crime-fraud exception bears the burden of establishing that the communications were made to further illegal purposes, not merely that they involved discussion of illegal conduct [8].

Application of the crime-fraud exception requires careful analysis of the client’s purpose in seeking legal advice. Courts typically examine whether the client was seeking guidance on how to comply with the law or how to evade or violate it. If a client asks a lawyer how to structure a transaction to comply with tax laws, that communication is privileged even if it involves minimizing tax liability. However, if the client seeks advice on how to conceal income or file false tax returns, the communication would not be privileged. The exception also covers situations where clients mislead their lawyers or provide false information in order to misuse the legal system, such as by filing frivolous claims or manufacturing evidence.

Communications About Physical Evidence

A particularly complex area involves situations where defense counsel becomes aware of the location of physical evidence related to criminal investigations. The Evidence Act’s language protecting “communications” has been interpreted by Indian courts to exclude physical evidence from privilege protection. If an accused person tells their lawyer where a weapon or other physical evidence can be found, the communication itself may be privileged, but the physical evidence is not. Courts have held that lawyers have ethical obligations not to conceal or destroy physical evidence, even if they learn about such evidence through privileged communications with clients. This principle reflects the understanding that privilege protects communications but cannot be used as a tool to obstruct justice by hiding evidence of crimes.

Exceptions and Limitations to Attorney-Client Privilege in India

Express Consent and Waiver

As explicitly stated in Section 126, attorney-client privilege can be waived by the client’s express consent. Waiver may be explicit, such as when a client authorizes their lawyer to disclose privileged communications to third parties or to testify about them in court. Waiver can also occur implicitly through conduct that is inconsistent with maintaining confidentiality, such as disclosing privileged communications to third parties who are not part of the legal representation. Once privileged information has been disclosed to outsiders without maintaining confidentiality, courts have found that the privilege has been waived not only for the disclosed information but potentially for all related privileged communications on the same subject matter.

The doctrine of waiver becomes particularly important in litigation contexts where parties selectively disclose privileged communications to advance their positions. If a party introduces evidence of privileged communications or uses such communications as the basis for claims or defenses, courts may find that the party has waived privilege over related communications. This principle prevents parties from using privilege as both a shield and a sword—revealing favorable privileged communications while hiding unfavorable ones. However, waiver typically extends only to communications on the same subject matter as the disclosed communications, not to all privileged communications generally.

Client as Witness

Section 129 establishes that when a client offers themselves as a witness, they may be compelled to disclose privileged communications to the extent necessary to explain evidence they have given. This limitation recognizes that parties cannot simultaneously claim the benefits of testifying while using privilege to prevent cross-examination on relevant matters. If a client testifies about events or circumstances that were the subject of communications with their lawyer, opposing counsel may cross-examine about those communications to the extent they relate to and explain the testimony given. However, this waiver remains limited—the client can be compelled to disclose only those privileged communications directly relevant to explaining their testimony, not all communications with counsel generally.

Communications in Presence of Third Parties

For attorney-client privilege to apply, communications must be made in confidence with the expectation of privacy. When third parties are present during communications between lawyers and clients, and those third parties are not essential to the legal representation, courts may find that the confidential nature of the communication has been destroyed and privilege does not attach. However, the presence of certain third parties does not waive privilege if their presence serves the purpose of facilitating the legal representation. For example, interpreters, accountants assisting with tax advice, or family members present to help clients understand legal matters may be considered part of the privileged communication. The key question is whether the third party’s presence was necessary or reasonably incidental to the legal consultation.

Professional Obligations and Ethical Considerations

Advocates Act and Bar Council Rules

Beyond the statutory provisions of the Evidence Act, Indian lawyers’ obligations regarding client confidentiality are also governed by the Advocates Act, 1961, and the Bar Council of India Rules. These professional regulations impose ethical duties on advocates to maintain client confidences even in circumstances where legal privilege might not strictly apply. Section 126 of the Evidence Act protects communications from compelled disclosure in legal proceedings, but the Advocates Act and Bar Council Rules establish broader confidentiality obligations that apply outside the courtroom as well. Lawyers cannot voluntarily disclose confidential client information even in contexts where they might not be legally compelled to keep it secret under the Evidence Act [9].

The Bar Council of India Rules specify that an advocate shall not disclose any communication made to them in the course of their employment except with the express consent of the client or as required by law. This professional obligation extends beyond the duration of the lawyer-client relationship and continues even after representation has ended. The rules also prohibit lawyers from using confidential information gained during representation to the disadvantage of former clients, even in matters unrelated to the original representation. Violations of these confidentiality obligations can result in professional disciplinary action, including suspension or removal from practice, separate from any legal consequences under the Evidence Act.

Conflicts Between Professional Duty and Legal Obligations

Lawyers occasionally face situations where their professional duty to maintain client confidences comes into tension with other legal obligations. For example, when lawyers inadvertently learn that their clients are engaging in ongoing fraud or illegal conduct that threatens harm to third parties, they must navigate between their duty of confidentiality and their obligations as officers of the court and members of society. Indian legal ethics generally prioritize client confidentiality, but this duty is not absolute when balanced against preventing serious harm or upholding the administration of justice. The Bar Council Rules permit limited disclosure of otherwise confidential information when necessary to prevent commission of a crime or to defend the lawyer against accusations of misconduct arising from the representation.

Comparative Analysis and Recent Developments

Evolution Through Judicial Interpretation

While the basic framework of attorney-client privilege in India has remained relatively stable since the enactment of the Evidence Act in 1872, judicial interpretation has refined and developed the doctrine over time. Courts have addressed numerous questions about the scope and application of privilege in contexts not specifically contemplated by the statutory language. For instance, courts have considered how privilege applies to electronic communications, group emails, and communications through intermediaries in the digital age. They have also addressed the treatment of privilege in insolvency proceedings, arbitration, and other alternative dispute resolution mechanisms where formal rules of evidence may not strictly apply.

Recent judicial decisions have emphasized that attorney-client privilege serves not merely the private interests of clients but also serves the public interest in promoting the effective administration of justice. This recognition has led courts to construe privilege broadly when doing so advances the purpose of enabling clients to obtain legal advice without fear of disclosure. At the same time, courts have been vigilant in policing attempts to misuse privilege to shield wrongdoing or obstruct legitimate investigations. The balancing of these competing considerations continues to shape the development of privilege doctrine through case law.

Challenges in Modern Legal Practice

Contemporary legal practice presents numerous challenges to traditional conceptions of attorney-client privilege in India. The proliferation of email and electronic communications has created vast volumes of potentially privileged materials that must be carefully managed. When documents are produced in litigation or investigations, lawyers must review enormous quantities of materials to identify and protect privileged communications, a task made more complex by the informal nature of email and the tendency for privileged and non-privileged materials to be commingled in electronic formats. Additionally, the growth of law firm sizes and the involvement of multiple lawyers in matters has raised questions about maintaining confidentiality within large organizations and with respect to conflicts between current and former clients.

The increasing specialization of legal practice has also created boundary questions about when consultations with non-lawyer professionals may be protected under privilege or related doctrines. While Section 127 extends privilege to interpreters and clerical staff, courts have been less clear about the status of communications involving accountants, financial advisors, or other consultants who assist lawyers in providing advice. In complex corporate and financial matters, effective legal advice often requires input from these specialists, yet their involvement may jeopardize privilege claims if not properly structured. These evolving challenges continue to test the adaptability of privilege doctrine to modern practice realities.

Conclusion

Attorney-client privilege occupies a central position in the Indian legal system, protecting the confidential relationship between lawyers and clients that is essential to the effective administration of justice. The privilege finds its primary expression in Sections 126 through 129 of the Indian Evidence Act, which establish both the scope of protection and its limitations. While the privilege provides robust protection for communications made in the course of seeking and providing legal advice, it is not absolute. Important exceptions exist for communications made to further crimes or frauds, and the privilege can be waived through client consent or conduct.

In corporate contexts, privilege enables companies to seek legal advice about complex commercial transactions, regulatory compliance, and disputes without fear that their consultations with counsel will be used against them. However, corporations must carefully structure their relationships with legal advisors and document the purposes of communications to preserve privilege claims, particularly where in-house counsel serve dual legal and business roles. In criminal matters, privilege provides crucial protection for communications between accused persons and their defense lawyers, enabling effective legal representation while recognizing important limitations when communications involve ongoing or future illegal conduct.

As legal practice continues to evolve with technological change and increasing complexity, the doctrine of attorney-client privilege in India will undoubtedly face new challenges requiring thoughtful application of established principles to novel circumstances. Courts, legislators, and the legal profession must continue to balance the important interests served by privilege—promoting candor in legal consultations and effective legal representation—against competing values including truth-seeking in judicial proceedings and the prevention of abuse of legal processes. The future development of privilege doctrine will require careful attention to these competing considerations to ensure that this ancient and essential principle continues to serve justice in contemporary contexts.

References

[1] Legal Service India. (n.d.). Attorney Client Privilege under Section 126 of Indian Evidence Act, 1872. Retrieved from https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-1403-attorney-client-privilege-under-section-126-of-indian-evidence-act-1872.html

[2] IndianKanoon.org. (n.d.). Section 126 in The Indian Evidence Act, 1872. Retrieved from https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1520037/

[3] Metalegal. (2025). When Courts Protect Lawyer-Client Talks: Privilege in Indian Law. Retrieved from https://www.metalegal.in/post/attorney-client-privilege-in-india

[4] iPleaders. (2020). Privileged Communication under Indian Evidence Act, 1872. Retrieved from https://blog.ipleaders.in/privileged-communication-under-indian-evidence-act-1872/

[5] Lexology. (2019). Legal Privilege & Professional Secrecy in India. Retrieved from https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=1a12eb24-5a71-42c6-890b-a10ea92aeefa

[6] AZB & Partners. (2021). Legal Privilege & Professional Secrecy – 2018 | India. Retrieved from https://www.azbpartners.com/bank/legal-privilege-professional-secrecy-2018-india/

[7] LiveLaw. (2020). What Is Attorney-Client Privilege? Retrieved from https://www.livelaw.in/know-the-law/attorney-client-privilege-indian-evidence-act-bar-council-of-india-rules-167667

[8] Government of India. (2020). The Indian Evidence Act, 1872. Retrieved from https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15351/1/iea_1872.pdf

Equal Remuneration Act, 1976: Legal Framework for Equal Pay in India

Introduction: The Foundation of Wage Equality in India

India’s journey toward workplace equality took a significant legislative turn with the enactment of the Equal Remuneration Act in 1976. This landmark legislation emerged from the constitutional mandate enshrined in Article 39 of the Indian Constitution, which directs the State to ensure equal pay for equal work for both men and women [1]. The Act was initially introduced as the Equal Remuneration Ordinance in 1975, coinciding with the International Women’s Year, and was subsequently enacted as permanent legislation to address the systemic gender-based wage discrimination that plagued Indian workplaces [2].

The timing of this legislation was particularly significant. During the 1970s, India witnessed growing awareness about gender inequality in employment, with women workers across various sectors receiving substantially lower wages than their male counterparts for performing identical or similar work. The Act sought to dismantle these discriminatory practices by establishing a legal framework that mandated equal remuneration and prohibited gender-based discrimination in recruitment and employment conditions.

The legislative intent behind the Equal Remuneration Act extends beyond mere wage parity. It represents a fundamental shift in recognizing women’s economic contributions and ensuring their rightful place in the workforce without being subjected to discriminatory treatment based solely on their gender. This legislation acknowledges that economic empowerment of women through fair remuneration is essential for achieving broader social and economic development goals.

Scope and Applicability: Understanding the Legislative Reach

The Equal Remuneration Act, 1976 possesses nationwide jurisdiction, extending to the entire territory of India. This pan-India applicability ensures that workers across all states and union territories are protected under its provisions, regardless of the nature or size of their establishment. The Act applies to both organized and unorganized sectors, covering establishments ranging from government undertakings to private enterprises, banking companies, mines, oilfields, major ports, and corporations established under Central Acts [1].

The legislation defines its applicability based on the nature of employment and the authority governing that employment. For establishments under the Central Government’s purview, including railway administrations, banking companies, mines, oilfields, major ports, and Central Government undertakings, the Central Government acts as the appropriate authority. For all other establishments, the State Government assumes this role. This dual administrative structure ensures effective implementation across diverse employment sectors while maintaining clear jurisdictional boundaries.

One crucial aspect of the Act’s scope is its definition of “remuneration,” which encompasses not merely basic wages but also includes all additional emoluments payable to employees, whether in cash or kind. This broad definition ensures that discrimination cannot be disguised through complex compensation structures that might pay women lower allowances, bonuses, or benefits while maintaining nominal wage parity. The Act specifically provides that remuneration includes all payments made to workers in respect of employment or work done, provided the terms of the employment contract are fulfilled.

The Act also defines what constitutes “same work or work of a similar nature,” establishing clear parameters for comparison. According to the legislation, such work refers to work requiring the same skill, effort, and responsibility when performed under similar working conditions by men or women. Importantly, the Act recognizes that minor differences in skill, effort, or responsibility that are not of practical importance in relation to employment terms and conditions should not be used to justify wage disparities [2].

Core Provisions: The Legal Mandate for Equal Pay

At the heart of the Equal Remuneration Act lies its primary mandate in Section 4, which prohibits employers from paying workers of one gender at rates less favorable than those paid to workers of the opposite gender for performing the same work or work of a similar nature. This provision establishes the fundamental principle of equal pay for equal work, making it illegal for employers to maintain gender-based wage differentials in any establishment or employment [1].

The Act incorporates important safeguards to prevent employers from circumventing its provisions. Section 4(2) explicitly prohibits employers from reducing the remuneration of any worker to comply with the equal pay requirement. This means that achieving wage parity must involve raising lower wages to match higher ones, rather than reducing higher wages to match lower ones. This protective provision ensures that the Act’s implementation benefits workers without creating unintended negative consequences.

Furthermore, Section 4(3) addresses situations where differential wage rates existed before the Act’s commencement. In such cases, the legislation mandates that the higher rate of remuneration shall become the standard rate payable to all workers performing the same or similar work, regardless of gender. This provision demonstrates the Act’s forward-looking approach, ensuring that historical discrimination does not perpetuate into the future.

Beyond remuneration, Section 5 of the Act addresses discrimination in recruitment and employment conditions. This section prohibits employers from making any discrimination against women during recruitment for the same work or work of a similar nature. The 1987 amendment expanded this provision to include discrimination in post-recruitment conditions such as promotions, training, and transfers [2]. This broader protection recognizes that wage discrimination often interconnects with other forms of employment discrimination, and addressing only wages would leave women vulnerable to other discriminatory practices.

The Act does acknowledge certain exceptions to its anti-discrimination mandate. It does not apply where employment of women in particular work is prohibited or restricted by existing laws. Additionally, the Act does not affect reservations or priorities for scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, ex-servicemen, or other specified categories in recruitment. These exceptions balance the Act’s equality objectives with other legitimate policy considerations and existing protective legislation.

Institutional Mechanisms: Enforcement and Implementation

The Equal Remuneration Act establishes robust institutional mechanisms to ensure effective implementation and enforcement of its provisions. Section 6 mandates the constitution of Advisory Committees by the appropriate government to advise on increasing employment opportunities for women. These committees must consist of at least ten members, with mandatory representation of fifty percent women, ensuring that women’s perspectives inform policy decisions regarding their employment [1].

The Advisory Committees serve multiple important functions. They evaluate the extent to which women may be employed in various establishments or employments, considering factors such as the number of women currently employed, the nature of work, working hours, suitability of employment for women, and the need for increasing women’s employment opportunities, including part-time employment. Based on their advice, the appropriate government may issue directions regarding the employment of women workers after providing opportunities for representations from concerned parties.

Section 7 establishes the adjudication mechanism for handling complaints and claims under the Act. The appropriate government appoints authorities, typically officers not below the rank of Labour Officer, to hear and decide complaints regarding contraventions of the Act and claims arising from non-payment of equal wages. These authorities possess jurisdiction within defined geographical limits and must follow prescribed procedures for receiving and processing complaints and claims [2].

The appointed authorities wield substantial powers in executing their functions. They enjoy all powers of a Civil Court under the Code of Civil Procedure for taking evidence, enforcing witness attendance, and compelling document production. These authorities can, after providing hearings to both applicants and employers and conducting necessary inquiries, direct employers to pay workers the differential amount between wages actually paid and wages that should have been paid for equal work. They can also order employers to take adequate steps to ensure compliance with the Act’s provisions.

The Act provides for an appellate mechanism, allowing aggrieved employers or workers to appeal decisions made by the primary authorities. Appeals must be filed within thirty days of the order, with provisions for condoning delays of up to an additional thirty days in cases where appellants were prevented by sufficient cause from filing within the original time limit. The appellate authority’s decision is final, with no further appeals permitted, ensuring timely resolution of disputes.

Regulatory Oversight: Inspection and Compliance Monitoring

The Equal Remuneration Act incorporates provisions for proactive regulatory oversight through the appointment of Inspectors who monitor compliance with the Act’s provisions. Section 9 empowers the appropriate government to appoint Inspectors for investigating whether employers are complying with the Act and rules made thereunder. These Inspectors are deemed public servants under the Indian Penal Code, providing them legal protections and imposing obligations associated with public office [1].

Inspectors possess wide-ranging powers to conduct effective oversight. Within their jurisdictional limits, they can enter any building, factory, premises, or vessel at reasonable times with necessary assistance. They can require employers to produce registers, muster rolls, or other documents relating to worker employment and examine these documents thoroughly. Inspectors may take evidence from any person on the spot or otherwise to ascertain compliance with the Act’s provisions [2].

The inspection regime extends to examining employers, their agents, servants, persons in charge of establishments, and any person reasonably believed to be or have been a worker in the establishment. Inspectors can make copies or take extracts from registers or other documents maintained under the Act. These comprehensive powers enable Inspectors to conduct thorough investigations and gather evidence of violations.

The Act imposes corresponding duties on persons subject to inspection. Any person required by an Inspector to produce documents or provide information must comply with such requisitions. Failure to cooperate with Inspectors carries penalties, reinforcing the seriousness of the inspection regime and ensuring that Inspectors can effectively perform their oversight functions.

Section 8 mandates that employers maintain prescribed registers and documents relating to workers employed by them. This record-keeping requirement serves multiple purposes: it facilitates inspections, provides evidence for adjudicating complaints and claims, and creates transparency regarding employment terms and remuneration practices. The specific registers and documents required are defined through rules made under the Act, allowing for flexibility in adapting requirements to different types of establishments and employments.

Penalties and Prosecution: Ensuring Accountability

The Equal Remuneration Act establishes a comprehensive penalty structure to deter violations and ensure accountability. The Act recognizes different categories of violations and prescribes graduated penalties based on the severity and nature of the offense. This differentiated approach acknowledges that some violations involve direct discrimination or payment of unequal wages, while others involve procedural non-compliance such as failure to maintain proper records.

Section 10 of the Act addresses penalties for various violations. For procedural violations such as failing to maintain registers or documents, failing to produce documents, refusing to give evidence, or refusing to provide information, the Act prescribes punishment with simple imprisonment for up to one month or fine up to ten thousand rupees or both. These penalties, while significant, reflect the relatively less serious nature of procedural non-compliance compared to substantive discrimination [1].

For more serious violations, Section 10(2) prescribes substantially higher penalties. Employers who make recruitment in contravention of the Act, pay unequal remuneration to men and women for the same or similar work, make discrimination between men and women workers in violation of the Act’s provisions, or fail to carry out directions issued by the appropriate government face fine of not less than ten thousand rupees but which may extend to twenty thousand rupees or imprisonment for a term of not less than three months but which may extend to one year or both for the first offense. For second and subsequent offenses, imprisonment may extend to two years, demonstrating the Act’s serious view of repeated violations [2].

Section 11 addresses situations where offenses are committed by companies. In such cases, every person who, at the time of the offense, was in charge of and responsible to the company for conducting its business is deemed guilty of the offense along with the company itself. This provision prevents companies from escaping liability by claiming that violations were committed by the corporate entity rather than individuals. However, the Act provides a defense for individuals who can prove that the offense was committed without their knowledge or that they exercised due diligence to prevent its commission.

The Act also recognizes situations where directors, managers, secretaries, or other company officers are directly involved in violations. If an offense is committed with the consent or connivance of, or is attributable to neglect by such officers, they are deemed guilty and liable for punishment. This provision ensures that corporate officers cannot hide behind corporate structures to avoid personal accountability for discriminatory practices.

Section 12 governs the cognizance and trial of offenses under the Act. No court inferior to a Metropolitan Magistrate or Judicial Magistrate of the first class can try offenses under the Act, ensuring that competent judicial authorities handle these cases. Courts can take cognizance of offenses either on their own knowledge, upon complaints made by the appropriate government or authorized officers, or upon complaints by aggrieved persons or recognized welfare institutions or organizations. This multiple-avenue approach for initiating prosecutions ensures that violations do not go unpunished due to lack of complaint mechanisms.

Judicial Interpretation: Landmark Cases and Legal Precedents

The Equal Remuneration Act has been the subject of significant judicial interpretation, with Indian courts, particularly the Supreme Court, playing a crucial role in defining the scope and application of its provisions. These judicial pronouncements have clarified ambiguous provisions, established principles for determining whether work is of the same or similar nature, and reinforced the Act’s objectives of eliminating gender-based wage discrimination.

The landmark case of Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co. Ltd. v. Audrey D’Costa [3] stands as one of the most important judicial decisions interpreting the Equal Remuneration Act. In this case, decided by the Supreme Court in 1987, a female stenographer challenged the practice of paying lower wages to female stenographers compared to their male counterparts performing identical work. The employer argued that the work performed by female and male stenographers was not of the same nature and that historical wage structures justified the differential treatment.

The Supreme Court rejected these arguments, holding that paying lesser wages to female stenographers violated the Equal Remuneration Act. The Court emphasized that wherever sex discrimination is alleged, there should be proper job evaluation before any further inquiry is made. If two jobs in an establishment are accorded the same classification, the same scale should apply to both, regardless of the gender of the workers. The Court recognized India’s ratification of the Convention Concerning Equal Remuneration for Men and Women Workers for Work of Equal Value and interpreted the Act consistently with India’s international obligations [3].

In the Air India v. Nergesh Meerza case [4], the Supreme Court addressed discriminatory service conditions affecting female flight attendants. Air India’s service regulations required female cabin crew to retire at age 35 or upon first pregnancy within four years of service, while male cabin crew faced no such restrictions. The Supreme Court struck down these provisions as unconstitutional and violative of equal treatment principles. The Court held that marriage or pregnancy cannot be grounds for terminating women’s employment, establishing important precedents regarding gender discrimination in employment conditions.

Another significant case, Randhir Singh v. Union of India [5], though not directly involving the Equal Remuneration Act, established the constitutional principle of equal pay for equal work as flowing from Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution. The Supreme Court held that equal pay for equal work is not merely a statutory right under the Equal Remuneration Act but is also a constitutional goal. This decision elevated the principle of equal remuneration beyond statutory protection, recognizing it as a fundamental aspect of equality guaranteed by the Constitution.

The Delhi High Court’s decision in Female Workers v. Controller, DDA [6] addressed a situation where female workers were being paid less than male workers for identical work. The Court held that the principle of equal pay for equal work applies even in the absence of specific regulations, as it flows from constitutional provisions. This decision reinforced that the Equal Remuneration Act codifies a constitutional principle rather than creating a new right, and courts can enforce wage equality even in situations not explicitly covered by the Act.

These judicial decisions have established several important principles. First, job evaluation must be conducted objectively, focusing on the actual work performed rather than on the gender of workers performing it. Second, historical wage structures or past practices cannot justify continuing gender-based wage discrimination. Third, the principle of equal pay for equal work must be interpreted broadly to encompass not just basic wages but all employment benefits and conditions. Fourth, employers bear the burden of justifying any wage differentials, and such justifications must be based on factors other than gender, such as qualifications, experience, or responsibilities.

International Context: Global Standards and India’s Commitments

India’s Equal Remuneration Act, 1976 aligns with international standards on gender equality and workers’ rights established through various international conventions and declarations. Understanding this international context helps appreciate the Act’s significance and its role in fulfilling India’s international obligations regarding gender equality in employment.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 100, titled the Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951, which India ratified, establishes the fundamental principle that men and women workers should receive equal remuneration for work of equal value [7]. This Convention defines remuneration to include basic wages and any additional emoluments payable directly or indirectly by the employer to the worker. India’s Equal Remuneration Act incorporates these international standards, demonstrating the country’s commitment to implementing its treaty obligations through domestic legislation.

The Convention emphasizes that equal remuneration means rates of remuneration established without discrimination based on sex. It requires ratifying countries to promote and ensure application of the principle through national laws, legally established wage-determining machinery, collective agreements, or a combination of these methods. India’s approach through the Equal Remuneration Act represents implementation of this Convention through national legislation, backed by enforcement mechanisms and penalties for violations.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948, recognizes in Article 23 that everyone, without discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work [8]. This fundamental human right forms part of the international human rights framework that influences national legislation worldwide. The Equal Remuneration Act gives effect to this international human rights standard in the Indian context, treating equal pay as a fundamental right rather than merely an economic policy consideration.

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which India ratified in 1993, requires state parties to eliminate discrimination against women in employment, ensuring equal rights regarding remuneration, including benefits, and equal treatment in respect of work of equal value [9]. CEDAW recognizes that economic empowerment through equal remuneration is essential for achieving gender equality. India’s Equal Remuneration Act predates its CEDAW ratification but demonstrates early recognition of these principles and commitment to gender equality in employment.

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, adopted at the Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995, identified women’s economic empowerment and equal access to economic resources as critical areas of concern. The Platform calls for eliminating occupational segregation and all forms of employment discrimination, including those related to remuneration. India’s participation in this conference and endorsement of the Beijing Declaration reinforced its commitment to implementing and strengthening legislation like the Equal Remuneration Act.

Contemporary Challenges: Implementation and Enforcement Issues

Despite the robust legal framework established by the Equal Remuneration Act, significant challenges persist in its effective implementation and enforcement. These challenges stem from various factors including lack of awareness, inadequate enforcement mechanisms, evolving nature of work relationships, and persistent social attitudes regarding women’s work.

One fundamental challenge is the lack of awareness about the Act’s provisions among both employers and workers. Many women workers, particularly in unorganized sectors and rural areas, remain unaware of their rights under the Act and the mechanisms available for redressal of grievances. Similarly, many small and medium enterprises lack proper understanding of their obligations under the Act, leading to inadvertent non-compliance or deliberate exploitation of this knowledge gap.

The informal and unorganized sector, which employs a substantial proportion of India’s workforce including large numbers of women, poses particular enforcement challenges. The Act’s enforcement mechanisms, primarily designed for formal sector establishments, struggle to reach informal sector workers who often work without written contracts, proper documentation, or clear employer-employee relationships. Home-based workers, agricultural laborers, and those in irregular employment frequently fall outside the Act’s effective reach despite being legally covered.

Occupational segregation presents another significant challenge. Women’s concentration in certain occupations or job categories that are predominantly female-dominated creates situations where direct wage comparisons become difficult. When women and men are not performing the same or similar work in the same establishment, establishing wage discrimination becomes more complex. This occupational segregation often masks systemic undervaluation of women’s work rather than reflecting genuine differences in work requirements.

The concept of “work of similar nature” itself creates interpretational challenges. Determining whether two jobs are sufficiently similar to warrant equal remuneration requires careful job evaluation considering skills, effort, responsibility, and working conditions. Employers sometimes manipulate job classifications, creating artificial distinctions between positions to justify wage differentials. The subjective elements in such evaluations can perpetuate discrimination if not conducted objectively and transparently.

Limited resources for enforcement agencies constitute a practical constraint. The number of Labour Officers and Inspectors appointed under the Act often proves insufficient to monitor compliance across the vast number of establishments nationwide. Inspectors face heavy workloads, limiting their capacity for proactive inspections and investigations. This resource constraint allows violations to go undetected and unpunished, undermining the Act’s deterrent effect.

The relatively low penalties prescribed under the Act, despite amendments increasing them, may not adequately deter violations, especially for larger establishments where the financial penalties represent minimal costs compared to potential savings from paying discriminatory wages. The imprisonment provisions are rarely invoked, further reducing the Act’s deterrent impact. Enforcement authorities often prefer conciliation and correction over prosecution, which, while promoting compliance, may reduce the perceived seriousness of violations.

Delays in adjudication of complaints and claims discourage workers from pursuing remedies. The time taken to resolve cases through the authorities appointed under Section 7 and subsequent appeals can extend for months or years. During this period, workers must continue working, often in the same establishment with the same employer, creating practical difficulties and potential retaliation risks. These delays reduce the Act’s effectiveness as a tool for timely redress of grievances.

Recent Developments: Evolving Landscape of Wage Equality

The landscape of wage equality in India continues to evolve, influenced by new legislation, policy initiatives, judicial developments, and changing workplace dynamics. These developments both complement and interact with the Equal Remuneration Act, creating a more comprehensive framework for addressing gender-based wage discrimination.

The Code on Wages, 2019, represents a significant recent development in India’s wage regulation framework. This Code consolidates four existing wage-related laws and includes provisions requiring equal wages for all genders for the same work or work of a similar nature [1]. While the Equal Remuneration Act remains in force, the Code on Wages extends the equal pay principle beyond gender to encompass all workers regardless of gender, treating it as a fundamental principle of wage regulation rather than specifically as a gender equality measure.

The Code on Social Security, 2020, another component of the new labour code framework, includes provisions relevant to women’s employment and economic security. It addresses maternity benefits, childcare facilities, and other social security measures that impact women’s ability to participate in the workforce on equal terms. These provisions complement the Equal Remuneration Act by addressing broader factors that affect women’s economic opportunities and workplace equality.

Technology and digital platforms have transformed employment relationships, creating new challenges and opportunities for wage equality. Platform-based work, gig economy jobs, and remote working arrangements often blur traditional employer-employee relationships, raising questions about the application of the Equal Remuneration Act to these new forms of work. Some platform workers may not be classified as “employees” in traditional legal terms, potentially placing them outside the Act’s direct protection.

Corporate governance initiatives and voluntary reporting mechanisms have emerged as complementary approaches to promoting wage equality. Some companies now conduct gender pay gap analyses and publicly report wage equality metrics as part of their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) commitments. While voluntary, these initiatives reflect growing recognition that gender pay equality represents both an ethical imperative and a business advantage in attracting and retaining talent.

Conclusion: The Path Forward for Wage Equality

The Equal Remuneration Act, 1976 represents a foundational pillar in India’s legal architecture for gender equality and workers’ rights. Nearly five decades after its enactment, the Act continues to serve as the primary legislative instrument for addressing gender-based wage discrimination in Indian workplaces. Its core principles of equal pay for equal work and prohibition of gender-based discrimination in recruitment and employment conditions remain as relevant today as when the Act was first introduced.

The Act’s significance extends beyond its specific provisions to embody a fundamental societal commitment to gender equality in economic opportunities. By establishing legal mechanisms for challenging wage discrimination and creating accountability frameworks for employers, the Act empowers women workers to assert their rights and seek redress for violations. The judicial interpretations of the Act have further strengthened its impact, clarifying ambiguities and reinforcing its anti-discrimination objectives.

However, the persistence of gender wage gaps and employment discrimination indicates that legal frameworks alone cannot achieve complete equality. Effective implementation of the Equal Remuneration Act requires sustained attention to several areas. Strengthening enforcement mechanisms through adequate resources for inspection and adjudication bodies would enhance the Act’s practical impact. Increasing penalties for violations to levels that truly deter discrimination would reinforce compliance incentives.

Expanding awareness about the Act’s provisions among employers and workers, particularly in unorganized sectors and rural areas, would enable more workers to exercise their rights and more employers to understand their obligations. Addressing occupational segregation and challenging social attitudes that undervalue women’s work require broader social transformation alongside legal enforcement. Adapting the Act’s framework to emerging forms of work relationships in the gig economy and platform-based employment would ensure continued relevance in evolving labor markets.

The path forward requires multi-stakeholder collaboration involving government agencies, employers, workers’ organizations, civil society, and judiciary. It demands recognition that wage equality represents not merely a legal obligation but a developmental imperative essential for achieving inclusive economic growth and social justice. As India pursues its development goals and seeks to harness its demographic dividend, ensuring equal remuneration for women workers must remain a priority.

The Equal Remuneration Act has established the legal foundation; building upon this foundation requires continued vigilance, robust enforcement, evolving jurisprudence, and societal commitment to the principles of equality and non-discrimination. Only through such comprehensive efforts can the Act’s promise of equal pay for equal work be fully realized for all women workers across India.

References

[1] Ministry of Labour & Employment, Government of India. (n.d.). Equal Remuneration Acts and Rules, 1976. Retrieved from https://labour.gov.in/womenlabour/equal-remuneration-acts-and-rules-1976

[2] India Code. (1976). The Equal Remuneration Act, 1976 (Act No. 25 of 1976). Retrieved from https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/1494

[3] Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co. Ltd. v. Audrey D’Costa & Anr. (1987) 2 SCC 469. Retrieved from https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/mackinnon-mackenzie-&-co.-ltd.-v.-audrey-d’costa:-affirming-equal-remuneration-rights/view

[4] Air India Statutory Corporation v. Nergesh Meerza. (1981) 4 SCC 335. Retrieved from https://razorpay.com/payroll/learn/equal-remuneration-act/

[5] Chief Labour Commissioner (Central). (n.d.). Equal Remuneration Act. Retrieved from https://clc.gov.in/clc/acts-rules/equal-remuneration-act

[6] International Labour Organization. (1951). Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951 (No. 100). Retrieved from https://labour.gov.in/sites/default/files/equal_remuneration_act_1976_0.pdf

[7] United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Retrieved from https://manupatracademy.com/LegalPost/Equal_Pay_for_Equal_Work_Statutory_Provisions_Judicial_Pronouncements

[8] United Nations. (1979). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Retrieved from https://labour.delhi.gov.in/labour/equal-remuneration-act-1976

[9] ClearTax. (2025). Equal Remuneration Act 1976. Retrieved from https://cleartax.in/s/equal-remuneration-act-1976

Published and Authorized by Prapti Bhatt

Implications of Section 281 of the Income Tax Act for Companies and Individuals

Introduction: Understanding the Protective Framework

The Income Tax Act of 1961 stands as the cornerstone legislation governing direct taxation in India, establishing a framework that balances revenue collection with taxpayer rights. Among its various provisions, Section 281 of the Income Tax Act carries substantial weight in property and asset transactions, often determining the fate of multimillion-rupee deals and creating ripples across corporate boardrooms and individual property transfers alike. This provision operates as a statutory safeguard, designed to prevent taxpayers from circumventing their legitimate tax obligations through hasty asset transfers when proceedings are underway or demands are outstanding.

When parties enter into transactions involving significant assets—whether shares, real estate, machinery, or securities—they encounter a critical checkpoint that can potentially invalidate their carefully negotiated agreements. This checkpoint emerges from a legislative intent to protect government revenue while simultaneously raising important questions about due process, buyer protection, and the balance between tax enforcement and commercial certainty. The provision under examination creates what legal practitioners describe as an “overriding charge” on assets, a concept that transforms the landscape of asset transactions in India and requires careful navigation by both sellers and purchasers.

The practical implications of this statutory mechanism extend far beyond theoretical legal discussions. Real estate developers entering into joint development agreements, corporate entities executing mergers and acquisitions, individuals transferring property to family members, and businesses restructuring their operations all find themselves confronting the requirements and consequences embedded within this provision. The stakes are particularly high because non-compliance can render transactions void against tax authorities, leaving purchasers vulnerable despite having paid substantial consideration and completed all other legal formalities.

Scope and Operation of Section 281 in Asset Transactions