Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

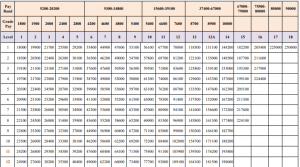

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

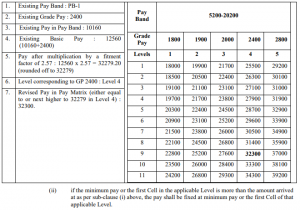

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

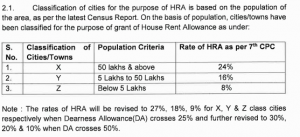

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

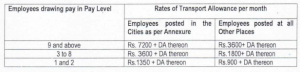

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Calcutta High Court Notifies Mandatory Child Access and Custody Guidelines Along With Parenting Plan: A New Era in Family Law Jurisprudence

Introduction

On September 26, 2025, the Calcutta High Court took a landmark step in family law jurisprudence by formally approving and publishing the Mandatory Child Access and Custody Guidelines on its official website[1]. This development marks a significant milestone for the State of West Bengal and the Union Territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, which previously lacked appropriate guidelines to address the complexities of child custody disputes. The introduction of these guidelines represents a progressive shift towards prioritizing the best interests of children caught in parental disputes while establishing a structured framework for determining custody and visitation rights.

The significance of these guidelines extends beyond mere procedural formality. They embody a judicial recognition that child custody matters require sensitivity, structure, and a child-centric approach rather than parent-centric considerations. The guidelines aim to minimize the psychological trauma that children experience during custody battles and ensure that judicial decisions are made with their welfare as the paramount concern. This article examines the regulatory framework governing child custody in India, analyzes the key provisions of the Calcutta High Court guidelines, explores relevant case law, and discusses the broader implications of this development for family law practice.

The Legal Framework Governing Child Custody in India

The Guardians and Wards Act, 1890

The primary legislation governing child custody matters in India is the Guardians and Wards Act, 1890, which provides a secular legal framework applicable across religious communities[2]. This colonial-era statute was enacted to consolidate and amend the law relating to guardians and wards, with the objective of providing a uniform law applicable to all classes of British India subjects. Despite being enacted over a century ago, the Act remains the foundational legislation for guardianship and custody matters in India.

The Guardians and Wards Act establishes the jurisdiction of courts in guardianship matters and sets forth the principles for appointing guardians. Under this Act, the District Court has the authority to appoint or declare guardians for the person or property of a minor. The Act empowers courts to direct any person having custody of a child to present the child before the court, ensuring judicial oversight in custody determinations. The legislation recognizes that guardianship involves both the custody of the minor’s person and the management of the minor’s property, treating these as distinct but related aspects of guardianship.

The Act’s provisions regarding the welfare of the minor have been consistently interpreted by Indian courts to mean that the child’s welfare supersedes all other considerations, including parental rights. Courts exercising jurisdiction under this Act are vested with parens patriae powers, enabling them to act as the ultimate guardian of minors and make decisions that serve the child’s best interests. The Act provides flexibility to courts in fashioning remedies appropriate to each case’s unique circumstances, recognizing that rigid rules cannot adequately address the diverse situations that arise in custody disputes.

The Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956

For Hindus, the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956 provides additional provisions specific to the community[3]. This Act defines the natural guardians for Hindu minors and establishes their rights and responsibilities. According to the Act, the father is the natural guardian of a Hindu minor for both the minor’s person and property, followed by the mother. However, the Act makes a significant exception for children below the age of five years, stating that the custody of such young children ordinarily remains with the mother.

The Act recognizes that the mother’s role is particularly crucial during a child’s tender years when the need for maternal care and nurturing is greatest. This provision reflects the legislative acknowledgment of the special bond between mother and infant child and the importance of continuity in caregiving during formative years. The Act also specifies that after the mother, other relatives may serve as natural guardians in a prescribed order of priority, ensuring that children have appropriate guardianship even in circumstances where both parents are unavailable.

The Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act operates in conjunction with the Guardians and Wards Act, with courts considering provisions from both statutes when adjudicating custody disputes involving Hindu families. The personal law provisions do not override the fundamental principle that the welfare of the child is paramount; rather, they provide guidance on presumptive guardianship while allowing courts to deviate from these norms when the child’s welfare demands a different arrangement.

Personal Laws of Other Religious Communities

Different religious communities in India are governed by their respective personal laws regarding custody and guardianship. Muslim personal law provides that the custody of a male child remains with the mother until the age of seven years and a female child until puberty, after which custody typically transfers to the father. Christian personal law, governed primarily by the Divorce Act and the Indian Christian Marriage Act, does not prescribe specific age-based custody rules but leaves custody determinations to judicial discretion guided by the child’s welfare.

Despite the existence of community-specific personal laws, Indian courts have consistently held that the Guardians and Wards Act provides an overarching framework that applies across religious lines. When conflicts arise between personal law provisions and the child’s welfare, courts invariably prioritize welfare considerations, recognizing that children’s rights transcend religious boundaries. This approach ensures that all children in India receive protection under a uniform standard that places their interests above religious or customary practices.

Constitutional Imperatives and Children’s Rights

The Indian Constitution does not explicitly address child custody matters, but several constitutional provisions have significant bearing on how courts approach such cases. Article 15(3) of the Constitution empowers the State to make special provisions for women and children, recognizing their vulnerability and need for protective measures. Article 21, which guarantees the right to life and personal liberty, has been interpreted by the Supreme Court to include the right to a dignified life, which for children encompasses the right to grow up in a nurturing environment that promotes their physical, mental, and emotional development.

India is also a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which has influenced judicial thinking on custody matters. The Convention emphasizes that in all actions concerning children, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration. Indian courts have increasingly incorporated this international standard into their jurisprudence, recognizing that children possess independent rights that deserve protection irrespective of parental claims.

The Calcutta High Court Child Access and Custody Guidelines: Key Features and Provisions

Background and Development

The Mandatory Child Access and Custody Guidelines published by the Calcutta High Court represent a culmination of evolving judicial thinking on custody matters and recognition of the need for standardized procedures. The State of West Bengal and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands had been operating without comprehensive guidelines, resulting in inconsistencies in how different judges approached custody disputes. The absence of uniform guidelines often led to prolonged litigation, unpredictable outcomes, and increased stress for families navigating the legal system.

The development of these guidelines involved consultation with legal experts, child psychologists, social workers, and family law practitioners. This multidisciplinary approach ensured that the guidelines address not only legal considerations but also the psychological and developmental needs of children. The guidelines draw upon best practices from other jurisdictions and incorporate insights from research on child development and the impact of parental separation on children.

Mandatory Parenting Plans

One of the most significant features of the Calcutta High Court child access and custody guidelines is the requirement for mandatory parenting plans in custody proceedings[4]. A parenting plan is a comprehensive document that outlines how parents will share responsibilities for their children’s upbringing following separation or divorce. The guidelines mandate that parents, with the assistance of counselors, must draw up an interim visitation plan within one week of receiving summons in custody proceedings.

This requirement represents a shift from adversarial litigation toward collaborative problem-solving. By requiring parents to develop parenting plans early in the proceedings, the guidelines encourage parents to focus on practical arrangements rather than engaging in acrimonious battles over custody labels. Parenting plans typically address various aspects of child-rearing, including daily routines, educational decisions, healthcare, religious upbringing, holiday schedules, and vacation arrangements. The requirement to develop these plans with counselor assistance ensures that parents receive professional guidance in creating arrangements that serve their children’s needs.

The emphasis on parenting plans reflects contemporary understanding that children benefit most when both parents remain actively involved in their lives despite the breakdown of the parental relationship. Research consistently shows that children adjust better to parental separation when they maintain meaningful relationships with both parents and when parents can cooperate in meeting their needs. Parenting plans facilitate this cooperation by establishing clear expectations and reducing opportunities for conflict.

Joint Custody Preference

The guidelines express a clear preference for joint custody arrangements wherever feasible[5]. Joint custody recognizes that children generally benefit from maintaining close relationships with both parents and that parental separation should not result in the loss of either parent from the child’s life. This preference represents a departure from traditional custody models that typically designated one parent as the primary custodian while relegating the other parent to periodic visitation.

Joint custody can take various forms, including joint legal custody where both parents share decision-making authority regarding major aspects of the child’s life, and joint physical custody where the child spends substantial time living with each parent. The guidelines recognize that joint custody arrangements require a degree of cooperation between parents and may not be appropriate in cases involving domestic violence, substance abuse, or other circumstances that compromise child safety.

The preference for joint custody aligns with the principle that children have a right to maintain relationships with both parents and that both parents have continuing responsibilities toward their children regardless of their marital status. However, the guidelines make clear that joint custody is not a rigid rule but rather a starting presumption that can be overcome when circumstances indicate that such an arrangement would not serve the child’s best interests.

Structured Visitation Frameworks

Recognizing that visitation arrangements often become sources of conflict between separated parents, the guidelines provide structured frameworks for visitation schedules. These frameworks offer templates for different visitation arrangements depending on factors such as the child’s age, the distance between parental residences, each parent’s work schedule, and the child’s school and activity commitments. By providing these templates, the guidelines reduce the need for litigation over visitation details and help ensure that children have predictable schedules that provide stability during a period of family transition.

The structured visitation frameworks address both regular visitation during the school year and special arrangements for holidays, school vacations, and significant occasions such as birthdays and religious festivals. The guidelines recognize that flexibility is necessary to accommodate changing circumstances while maintaining consistency that helps children feel secure. They encourage parents to communicate about schedule adjustments and to prioritize their children’s needs over personal convenience or the desire to limit the other parent’s time with the child.

Role of Counselors and Mediation

The Calcutta High Court guidelines place significant emphasis on counseling and mediation as alternatives to adversarial litigation[6]. The requirement that parents work with counselors in developing parenting plans reflects recognition that custody disputes often involve deep emotional issues that benefit from professional intervention. Counselors can help parents process their feelings about separation, improve communication skills, and focus on their children’s needs rather than their grievances against each other.

Mediation provides a structured process through which parents can negotiate custody and visitation arrangements with the assistance of a neutral third party. Unlike litigation, which produces winners and losers, mediation encourages collaborative problem-solving and helps parents develop solutions tailored to their family’s unique circumstances. The guidelines encourage courts to refer custody matters to mediation early in the proceedings, reserving judicial decision-making for cases where parents cannot reach agreement despite mediation efforts.

The emphasis on counseling and mediation reflects understanding that the outcome of custody proceedings is less important than the process through which that outcome is reached. Children benefit when their parents can communicate effectively and cooperate in meeting their needs, skills that counseling and mediation help develop. Moreover, parents who participate in developing custody arrangements are more likely to comply with those arrangements than parents who have decisions imposed upon them by courts.

Judicial Precedents Shaping Child Custody Law

Nil Ratan Kundu v. Abhijit Kundu (2008)

The Supreme Court’s decision in Nil Ratan Kundu v. Abhijit Kundu represents one of the most comprehensive statements of principles governing child custody in Indian jurisprudence[7]. In this case, the Court addressed a custody dispute involving grandparents seeking custody of their grandson against the child’s father. The Court held that in custody matters, the welfare of the child is paramount and supersedes the rights of parents or other individuals seeking custody.

The Court emphasized that welfare of the child is not limited to physical well-being but encompasses the child’s moral, ethical, and emotional development. The judgment recognized that courts must consider multiple factors in assessing welfare, including the child’s age, sex, religion, character and capacity of proposed guardians, the child’s wishes if the child is old enough to form intelligent preferences, and the continuity and stability of the existing custody arrangement. The Court stressed that courts should not mechanically apply presumptions about maternal or paternal custody but must examine each case’s specific circumstances.

Nil Ratan Kundu established several important principles that continue to guide custody determinations. First, the judgment affirmed that the child’s welfare is not synonymous with parental rights, and courts must distinguish between the right of guardianship and the right of custody. Second, the Court held that better financial resources alone do not determine custody, as love, affection, and ability to provide emotional support are equally or more important. Third, the judgment recognized that stability is a crucial element of child welfare, and courts should be reluctant to disturb existing custody arrangements that are working well for the child.

Gaurav Nagpal v. Sumedha Nagpal (2009)

In Gaurav Nagpal v. Sumedha Nagpal, the Supreme Court reiterated the paramountcy of child welfare while emphasizing that courts must examine all relevant factors before making custody determinations[8]. The case involved a custody dispute between parents where the mother had taken the child to India from the United States. The Court held that while international conventions and comity considerations are relevant in international child custody disputes, the welfare of the child remains the foremost consideration.

The Court observed that in determining welfare, courts should consider factors such as the child’s age and sex, the character and capacity of parents, the child’s ordinary wishes if the child is of sufficient age and maturity to form intelligent opinions, and which parent has shown greater affection and care for the child. The judgment emphasized that courts should avoid disturbing arrangements that are working satisfactorily for the child unless compelling reasons exist to do so.

Thrity Hoshie Dolikuka v. Hoshiam Shavaksha Dolikuka (1982)

This early Supreme Court decision established the foundational principle that the welfare of the child is the paramount consideration in custody disputes, superseding even parental rights[9]. The Court held that when determining custody, courts must focus on what serves the child’s best interests rather than on vindicating parental claims. This principle has been consistently followed in subsequent decisions and forms the bedrock of Indian child custody jurisprudence.

The Thrity Hoshie Dolikuka judgment recognized that while parents have natural claims to custody of their children, these claims are subordinate to considerations of child welfare. The Court observed that factors such as which parent was responsible for marital breakdown are irrelevant to custody determinations, as the focus must remain on the child’s needs rather than apportioning blame between parents. This approach reflects maturity in judicial thinking, recognizing that children should not be used as rewards or punishments in divorce proceedings.

Implications and Implementation Challenges of Child Access and Custody Guidelines

Impact on Legal Practice

The Calcutta High Court child access and custody guidelines will significantly impact how family law practitioners approach custody cases in West Bengal and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Lawyers will need to shift from purely adversarial strategies toward more collaborative approaches that emphasize negotiation and problem-solving. The mandatory requirement for parenting plans means that practitioners must be prepared to assist clients in developing comprehensive proposals that address all aspects of child-rearing rather than simply arguing for maximum custody time.

The child access and custody guidelines also place new responsibilities on family court judges, who must ensure compliance with procedural requirements while maintaining focus on substantive justice. Judges will need to carefully review proposed parenting plans to ensure they adequately address children’s needs and do not merely reflect one parent’s preferences imposed on the other. The emphasis on counseling and mediation means that courts will need to work closely with mental health professionals and develop referral networks that can provide timely services to families in custody disputes.

Training and Capacity Building

Effective implementation of the child access and custody guidelines requires extensive training for all stakeholders in the family justice system. Judges and court personnel need training on child development, domestic violence dynamics, substance abuse issues, and other topics relevant to custody determinations. Counselors and mediators must understand the legal framework within which they operate and develop skills specific to working with high-conflict families. Lawyers need education on collaborative law techniques and the psychology of separation and divorce.

The Calcutta High Court will likely need to establish training programs and continuing education requirements to ensure that all professionals working on custody cases have necessary competencies. Professional organizations, including bar associations and mental health professional bodies, can play important roles in developing and delivering training. Academic institutions offering law and counseling programs should incorporate family law and child development content into their curricula to prepare future professionals for practice in this area.

Resource Allocation

The successful implementation of the guidelines depends on adequate resource allocation to family courts. Courts will need additional staff to manage the increased administrative requirements associated with parenting plan review and monitoring. Funding must be available for counseling and mediation services, with provisions to ensure that indigent parties can access these services. Courts may need to establish child custody evaluation units staffed by psychologists and social workers who can conduct assessments in complex cases.

The guidelines may initially increase case processing times as courts and practitioners adjust to new procedures. However, proponents argue that investing resources in front-end processes like counseling and mediation will ultimately reduce litigation by helping more families reach agreements. The guidelines may also reduce the need for post-judgment modification proceedings by establishing more workable initial arrangements that better meet children’s needs.

Monitoring and Enforcement

The guidelines must include mechanisms for monitoring compliance with custody and visitation orders and enforcing those orders when parents fail to comply. Non-compliance with visitation schedules is a common problem in custody cases, often leading to return trips to court and continuing conflict. Courts need procedures for quickly addressing compliance issues and remedies that encourage cooperation while protecting children from exposure to parental conflict.

The guidelines may contemplate various enforcement mechanisms, including contempt proceedings for willful violations, modification of custody arrangements when one parent systematically interferes with the other’s visitation, and referral to parenting coordination services in high-conflict cases. Some jurisdictions have found success with specialized compliance programs that combine monitoring, incentives for compliance, and graduated sanctions for violations. The Calcutta High Court may adopt similar approaches as it gains experience implementing the guidelines.

Comparative Perspectives: Guidelines in Other Jurisdictions

Several other High Courts in India have adopted similar guidelines for child custody matters, providing models that may have influenced the Calcutta High Court’s approach. The Bombay High Court was among the first to formalize custody and access guidelines, recognizing the need for structured approaches to these sensitive matters. The guidelines developed by various High Courts share common themes, including emphasis on child welfare, preference for joint custody, structured visitation schedules, and use of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms.

Beyond India, many jurisdictions have developed statutory frameworks or judicial guidelines for custody determinations. The American Law Institute’s Principles of the Law of Family Dissolution proposes an approximation rule under which custody arrangements should approximate the time each parent spent performing caretaking functions before separation. This approach aims to provide continuity for children while avoiding gender-based presumptions about custody. Other jurisdictions emphasize the importance of maintaining sibling relationships and extended family connections in custody arrangements.

International instruments such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction provide frameworks that influence domestic custody law. The emphasis in these instruments on considering children’s views, maintaining family relationships, and protecting children from abduction reflects evolving international consensus on children’s rights. Indian courts increasingly reference international standards in custody cases, demonstrating India’s integration into global human rights jurisprudence.

Future Directions and Reforms for Child Custody Laws in India

Legislative Reform Proposals

While judicial guidelines like those issued by the Calcutta High Court represent important progress, comprehensive legislative reform would provide more uniform standards across India. The Law Commission of India has examined guardianship and custody laws and recommended reforms to address gaps and inconsistencies. Proposed reforms include updating the archaic language of the Guardians and Wards Act, providing specific criteria for courts to consider in custody determinations, and establishing uniform procedures across jurisdictions.

Reform proposals also address the need for specialized family courts with jurisdiction over all family law matters. Currently, custody cases may be filed in civil courts, family courts, or as ancillary proceedings in matrimonial courts, depending on the jurisdiction and nature of the case. This fragmentation creates inefficiencies and inconsistencies. A unified family court system with trained judges, integrated services, and specialized procedures could better serve families experiencing separation and divorce.

Emerging Issues in Child Custody

Child custody law must continually evolve to address emerging family structures and social changes. The increasing prevalence of non-marital cohabitation raises questions about custody rights of unmarried parents. Same-sex couples raising children present issues that traditional legal frameworks did not contemplate. Advances in reproductive technology, including surrogacy and assisted reproduction, create complex questions about legal parentage and custody rights.

The impact of technology on children’s lives presents new custody considerations. Questions about screen time, social media use, online privacy, and exposure to inappropriate content require parents to make decisions that may generate conflict. Custody arrangements need to address these issues, potentially requiring provisions about technology use and parental monitoring. The rise of remote work and geographic mobility creates opportunities for creative custody arrangements but also challenges in maintaining stability for children.

Child Participation in Custody Proceedings

International human rights standards increasingly emphasize children’s right to be heard in proceedings affecting them. While Indian law requires courts to consider children’s preferences when children are old enough to form intelligent opinions, procedures for ascertaining and giving effect to children’s views remain underdeveloped. Future reforms should establish age-appropriate mechanisms for children to express their preferences and concerns without placing them in the middle of parental conflicts.

Child participation mechanisms might include private judicial interviews, appointment of children’s representatives or guardians ad litem, and use of child specialists who can communicate with children and convey their perspectives to courts. Care must be taken to ensure that children’s participation is voluntary, that children receive adequate information about proceedings in age-appropriate language, and that children’s expressed preferences are understood in context rather than treated as determinative. Balancing children’s participatory rights with protection from harmful exposure to parental conflict remains an ongoing challenge.

Conclusion

The notification of Mandatory Child Access and Custody Guidelines by the Calcutta High Court represents a significant advancement in family law practice in West Bengal and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. These guidelines provide much-needed structure and consistency to custody proceedings while reinforcing the fundamental principle that child welfare must guide all custody determinations. By mandating parenting plans, expressing preference for joint custody, emphasizing counseling and mediation, and establishing clear procedural requirements, the guidelines aim to reduce the trauma that children experience during custody disputes and promote outcomes that serve their long-term interests.

The legal framework governing child custody in India, encompassing the Guardians and Wards Act, personal laws, constitutional provisions, and evolving case law, reflects continuing judicial commitment to protecting children’s welfare. Supreme Court decisions like Nil Ratan Kundu have established that children’s rights supersede parental claims and that courts must consider multiple factors in assessing welfare. The Calcutta High Court guidelines build upon this jurisprudential foundation while providing practical tools for implementing these principles.

Successful implementation of the guidelines will require sustained effort from all stakeholders in the family justice system. Training and capacity building for judges, lawyers, counselors, and mediators is essential. Adequate resources must be allocated to courts and support services. Monitoring mechanisms must ensure compliance with custody orders while addressing violations promptly. As experience accumulates, the guidelines may require refinement to address unforeseen issues and incorporate lessons learned.

The broader significance of the Calcutta High Court guidelines extends beyond their immediate jurisdictional scope. They represent judicial recognition that child custody law must evolve to meet contemporary families’ needs and incorporate insights from child development research and clinical practice. Other jurisdictions may look to these guidelines as models for their own reforms. Legislative bodies may draw upon the guidelines in developing comprehensive custody law reforms. Ultimately, the success of these guidelines will be measured not by their legal sophistication but by their impact on children’s lives, ensuring that children of separated parents receive the love, support, and stability they need to thrive.

References

[1] Calcutta High Court Notifies Mandatory Child Access & Custody Guidelines Along With Parenting Plan. (2025, September 29). LiveLaw. https://www.livelaw.in/high-court/calcutta-high-court/calcutta-high-court-notifies-mandatory-child-access-custody-guidelines-alongwith-parenting-plan-305441

[2] The Guardians and Wards Act, 1890. India Code. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2318/1/189008.pdf

[3] The Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956. India Code. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1649/1/195632.pdf

[4] Child Custody & Parenting: Calcutta High Court Issues Guidelines. (2025, September). LawBeat. https://lawbeat.in/news-updates/child-custody-parenting-calcutta-high-court-issues-comprehensive-guidelines-1532117

[5] Calcutta High Court. (2025). Notice on Child Access & Custody Guidelines. Official Website. https://www.calcuttahighcourt.gov.in/Notice-Files/general-notice/15363

[6] Supreme Court Half Yearly Digest 2025: Family Law. (2025, September 30). LiveLaw. https://www.livelaw.in/supreme-court/supreme-court-half-yearly-digest-family-law-2025-305409

[7] Nil Ratan Kundu & Anr vs Abhijit Kundu, (2008) 9 SCC 413. Indian Kanoon. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/687286/

[8] Stability of child is of paramount consideration in custody battle: Supreme Court sets aside Orissa HC judgment granting custody to father. (2024, March 14). SCC Times. https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2024/03/06/stability-child-paramount-consideration-custody-battle-supreme-court-sets-aside-orissa-hc-judgment-granting-custody-father/

[9] The Guardians and Wards Act, 1890. Indian Kanoon. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1874830/

TRAI Releases Recommendations on Digital Radio Broadcast Policy for Private Broadcasters: A Comprehensive Legal Analysis

Introduction

On October 2, 2025, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India released groundbreaking recommendations that will fundamentally reshape the landscape of digital radio broadcast policy in the country. This policy framework introduces digital radio broadcasting services for private broadcasters, marking a significant departure from the exclusively analog FM radio system that has operated for decades. The recommendations cover critical aspects including technology standards, spectrum allocation mechanisms, licensing terms, and revenue-sharing models, all aimed at modernizing India’s radio broadcasting infrastructure while maintaining regulatory oversight and consumer protection.

The regulatory authority’s recommendations emerge at a crucial juncture when global broadcasting is transitioning toward digital platforms. These guidelines represent the culmination of extensive stakeholder consultations that began with a consultation paper released in September 2024, followed by an open house discussion conducted on January 8, 2025. The recommendations address fundamental questions about how India will implement digital radio technology, assign spectrum frequencies, and regulate this emerging segment while ensuring fair competition and quality service delivery to listeners across the nation [1].

Constitutional and Legislative Framework Governing Broadcasting

Constitutional Provisions and Spectrum Ownership

The constitutional foundation for regulating airwaves and broadcasting in India derives from the exclusive authority vested in the Union Government under Entry 31 of List I (Union List) of the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution of India, which covers “posts and telegraphs; telephones, wireless, broadcasting and other like forms of communication.” This constitutional mandate establishes the central government’s supreme authority over all forms of wireless communication, including radio broadcasting. The principle of state ownership of spectrum has been consistently affirmed by Indian courts, recognizing that radio frequencies constitute a scarce public resource that must be managed in the public interest.

The Telecommunications Act, 2023, which received presidential assent on December 24, 2023, fundamentally redefines this regulatory landscape. Section 4(1) of this Act explicitly declares that “The Central Government, being the owner of the spectrum on behalf of the people, shall assign the spectrum in accordance with this Act, and may notify a National Frequency Allocation Plan from time to time” [2]. This provision crystallizes the state’s custodianship over electromagnetic spectrum and establishes the legal foundation for spectrum assignment, whether through auction or administrative processes.

The TRAI Act and Regulatory Authority

The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Act, 1997, as amended, empowers TRAI to make recommendations on various aspects of telecommunication and broadcasting services. Section 11(1) of the TRAI Act specifically mandates that the authority shall, from time to time, make recommendations either on its own initiative or on a request from the licensor on matters including terms and conditions of licenses, revocation of licenses, and measures to facilitate competition and promote efficiency in telecommunication services. The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting invoked this provision under Section 11 of the TRAI Act, 1997, when it sought recommendations from TRAI for formulating a digital radio broadcast policy [3].

The regulatory framework operates through a collaborative mechanism where the ministry requests recommendations, TRAI conducts extensive consultations and research, and ultimately provides detailed recommendations that the government considers for implementation. This process ensures that policy formulation benefits from technical expertise, stakeholder input, and regulatory experience while maintaining governmental accountability for final decisions.

Key Recommendations of TRAI’s Digital Radio Broadcasting Policy

Simulcast Mode Implementation

The cornerstone of TRAI’s recommendations is the adoption of simulcast mode for digital radio broadcasting. Under this framework, broadcasters will transmit both analog and digital signals simultaneously on the same frequency, allowing for a gradual transition period during which listeners can access services using existing analog receivers while the market develops digital radio infrastructure. Each assigned frequency will accommodate one analog channel, three digital channels, and one data channel, significantly expanding the content delivery capacity compared to traditional analog broadcasting that permits only a single channel per frequency [4].

New broadcasters entering the market will be mandated to commence operations in simulcast mode from the outset. Existing FM radio broadcasters, however, will have the flexibility to migrate to simulcast mode on a voluntary basis, recognizing the substantial infrastructure investments and operational adjustments required for such transition. This graduated approach balances the policy objective of technological advancement with pragmatic considerations of industry capacity and consumer readiness. Broadcasters must commence simulcast operations within two years of either the conclusion of the auction process or their acceptance of the migration option, establishing clear timelines for implementation while providing sufficient lead time for technical preparations.

Geographic Scope and City Classification

The recommendations propose a phased rollout strategy beginning with major metropolitan areas. The initial implementation will cover four cities classified as “A+” category, specifically Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, and Chennai, representing India’s largest metropolitan markets with the most developed broadcasting infrastructure and listener bases. The second tier includes nine “A” category cities: Hyderabad, Bengaluru, Ahmedabad, Surat, Pune, Jaipur, Lucknow, Kanpur, and Nagpur [5].

This strategic geographic prioritization reflects economic viability considerations, existing infrastructure availability, and population density factors. These thirteen cities collectively represent substantial listener markets and possess the technical infrastructure necessary for supporting digital broadcasting services. The phased approach allows for learning from initial implementations, addressing technical challenges, and refining regulatory mechanisms before expanding to smaller markets.

Technology Standards and Interoperability

TRAI has recommended that India adopt a single digital radio technology standard in the VHF Band II frequency range to ensure nationwide interoperability and avoid market fragmentation. However, the recommendations notably refrain from specifying a particular technology standard, instead urging the government to undertake comprehensive consultations with broadcasters, equipment manufacturers, and other stakeholders before making this critical determination. This approach recognizes that technology selection involves complex trade-offs regarding equipment costs, audio quality, spectrum efficiency, and international compatibility.

The emphasis on a unified standard stems from practical considerations of receiver manufacturing economies of scale, consumer convenience, and network efficiency. A fragmented technology landscape would complicate device manufacturing, increase consumer costs, and potentially create regional incompatibilities that undermine the policy’s objectives of expanding service availability and enhancing listener experience.

Spectrum Assignment Methodology

The recommendations advocate for auction-based spectrum assignment, aligning with the market-driven allocation methodology prescribed under the Telecommunications Act, 2023. Section 4(4) of the Act establishes that “The Central Government shall assign spectrum for telecommunication through auction except for entries listed in the First Schedule for which assignment shall be done by administrative process.” While the First Schedule includes public broadcasting services among categories eligible for administrative allocation, private commercial radio broadcasting falls outside these exceptions, necessitating competitive bidding processes [2].

The auction mechanism serves multiple policy objectives including ensuring transparent allocation procedures, discovering market-determined pricing for scarce spectrum resources, and promoting efficient utilization by assigning frequencies to entities that value them most highly. The recommendations specify that reserve prices for spectrum in different city categories should be established based on comprehensive valuation methodologies that account for market potential, existing analog frequency prices, and technological advantages of digital broadcasting.

Licensing Terms and Regulatory Conditions for Digital Radio Broadcast

Authorization Period and Renewal

The recommendations propose authorization periods of fifteen years for digital radio broadcasting licenses, providing operators with substantial certainty for long-term business planning and infrastructure investments. This duration aligns with international practices in broadcasting licensing and reflects the capital-intensive nature of establishing broadcasting networks. The extended license term enables broadcasters to amortize equipment costs, develop audience relationships, and establish sustainable business models without the uncertainty of frequent renewal processes.

Authorization under the new framework will be granted pursuant to Section 3(1) of the Telecommunications Act, 2023, which requires that “Any person intending to provide telecommunication services or establish, operate, maintain or expand telecommunication network shall obtain an authorisation from the Central Government, subject to such terms and conditions, including fees or charges, as may be prescribed” [2]. This provision establishes the legal foundation for licensing digital radio services and empowers the government to prescribe comprehensive terms covering technical standards, content regulations, and financial obligations.

Revenue Sharing and Fee Structure

The recommendations propose that license fees should be calculated based on adjusted gross revenue principles, maintaining consistency with the fee structure applicable to existing analog FM radio operations. Significantly, the recommendations specify that revenue generated from streaming digital radio content through internet platforms should be included in gross revenue calculations for fee purposes. This provision addresses the convergence of traditional broadcasting and digital distribution channels, ensuring that regulatory obligations extend to all revenue streams derived from licensed broadcasting activities.

The inclusion of streaming revenue in the fee base reflects evolving consumption patterns where listeners increasingly access radio content through mobile applications and internet platforms rather than traditional receivers. This approach prevents regulatory arbitrage where broadcasters might structure operations to minimize reportable revenues while still monetizing their content through digital channels.

Analog Sunset Provisions

Rather than establishing a definitive date for terminating analog broadcasting, the recommendations adopt a flexible approach that defers the analog sunset decision until sufficient data exists regarding digital radio adoption, receiver penetration, and service quality. The recommendations specify that the sunset date should be determined after evaluating the progress of digital radio broadcasting at a later stage, allowing policymakers to assess market development before committing to an irreversible transition timeline.

This pragmatic approach recognizes the substantial installed base of analog receivers in Indian households and vehicles, the potentially slow pace of consumer equipment upgrades, and the need to avoid service disruptions for listeners who continue relying on analog technology. The gradual transition model protects consumer interests while encouraging market-driven adoption of digital technology as receiver prices decline and content advantages become apparent.

Legal and Regulatory Challenges for Digital Radio Broadcast

Content Regulation and Program Code Compliance

Digital radio broadcasters will remain subject to content regulations established under the Cable Television Networks Rules, 1994, and the Programme Code prescribed under the All India Radio Code. These regulations govern aspects including decency standards, restrictions on content that offends religious sentiments, prohibition of obscene or defamatory material, and requirements for balanced presentation of news and current affairs. The convergence of radio broadcasting with data services raises novel questions about the applicability of these regulations to non-audio content transmitted through the data channel component of digital broadcasting.

The regulatory framework must address how traditional content standards apply to interactive services, data broadcasting, and multimedia content that digital technology enables. These questions involve balancing free speech protections, cultural sensitivities, and regulatory oversight in an evolving technological environment that blurs traditional distinctions between broadcasting, telecommunications, and internet services.

Competition Law Considerations

The auction-based allocation mechanism and market entry conditions raise important competition law questions regarding market concentration, cross-media ownership, and barrier to entry. Section 11(2) of the TRAI Act empowers the authority to ensure technical compatibility and effective competition, while recent amendments to the Act enable TRAI to direct entities to abstain from predatory pricing harmful to competition and long-term sector development.

The digital radio policy must navigate tensions between allowing sufficient market concentration to achieve economies of scale while preventing dominant operators from leveraging market power to exclude competitors or harm consumer interests. Cross-ownership restrictions, spectrum caps, and merger review processes constitute important regulatory tools for maintaining competitive market structures.

Spectrum Interference and Technical Coordination

The simultaneous transmission of analog and digital signals on the same frequency in simulcast mode creates potential for interference issues that require careful technical management. The recommendations contemplate detailed technical specifications regarding transmission power levels, modulation schemes, and guard bands to minimize interference both between analog and digital signals and among adjacent frequency assignments. The Wireless Planning and Coordination Wing of the Department of Telecommunications bears responsibility for frequency planning and interference resolution, exercising powers under the Telecommunications Act, 2023.

Section 8(1) of the Act authorizes the Central Government to “establish by notification, such monitoring and enforcement mechanism as it may deem fit to ensure adherence to terms and conditions of spectrum utilisation and enable interference-free use of the assigned spectrum” [2]. This provision provides the legal foundation for establishing technical standards and enforcement mechanisms necessary for managing the complex radio frequency environment that digital broadcasting creates.

Case Law Precedents and Judicial Interpretations

Spectrum as Public Property

The foundational principle that electromagnetic spectrum constitutes public property managed by the state on behalf of citizens received authoritative endorsement from the Supreme Court in the case of Centre for Public Interest Litigation v. Union of India, where the Court observed that natural resources including airwaves belong to the public and must be distributed in a manner that serves the common good. While this judgment primarily addressed allocation of 2G spectrum for mobile telephony, its principles apply equally to broadcasting spectrum.

The Court’s reasoning emphasized that when the state acts as custodian of scarce natural resources, it must do so in a manner that maximizes public benefit rather than private gain, necessitating transparent allocation procedures and fair pricing mechanisms. These principles undergird the auction-based allocation methodology that TRAI’s recommendations propose for digital radio spectrum.

Regulatory Authority and Ministerial Powers

The Supreme Court in Cellular Operators Association of India v. Telecom Regulatory Authority of India clarified the respective roles of TRAI and the government in licensing and regulatory matters. The Court held that while TRAI possesses recommendatory powers on licensing terms and conditions, the government retains ultimate decision-making authority regarding license grants, rejections, and modifications. However, the government must seriously consider TRAI’s recommendations and cannot arbitrarily deviate without cogent reasons.

This division of authority reflects the institutional design where TRAI brings technical expertise and regulatory independence to policy formulation while maintaining governmental accountability through ministerial control over final decisions. In the context of digital radio policy, this means that while TRAI’s recommendations carry substantial weight, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting retains discretion in implementation details.

International Comparisons and Best Practices

European Digital Radio Transition

European countries have pursued varied approaches to digital radio implementation, with Norway becoming the first nation to completely switch off FM broadcasting in 2017. The Norwegian transition provided valuable lessons about the importance of receiver subsidies, extended transition periods, and maintaining analog services in areas with limited digital coverage. The United Kingdom has adopted a more gradual approach, requiring 50 percent digital listening share and nationwide coverage before contemplating analog shutdown.

These international experiences inform India’s simulcast approach and flexible sunset provisions, recognizing that successful digital transition requires consumer readiness, affordable receiver availability, and demonstrated service quality advantages. The gradual approach allows the market to develop organically while avoiding the service disruptions and public resistance that premature analog termination might generate.

Technology Standard Selection

Different regions have adopted various digital radio standards, with DAB+ dominating in Europe and Australia, HD Radio prevalent in the United States, and DRM gaining traction in some developing markets. Each standard presents distinct trade-offs regarding spectrum efficiency, audio quality, receiver costs, and backward compatibility. TRAI’s recommendation that India select a single standard after stakeholder consultation reflects awareness that technology selection involves balancing technical performance, economic viability, and market acceptance factors.

The choice of technology standard will profoundly influence receiver manufacturing costs, content delivery capabilities, and the competitive dynamics of the digital radio market. International interoperability considerations also matter, as receiver manufacturers achieve economies of scale by producing devices for multiple markets using common standards.

Implementation Challenges and Future Outlook for Digital Radio Broadcasting

Infrastructure Investment Requirements

The transition to digital radio broadcasting necessitates substantial capital investment in transmission equipment, studio infrastructure, and technical systems. Existing FM broadcasters contemplating migration must evaluate whether the potential audience reach and revenue advantages justify the required expenditures, particularly during the extended simulcast period when they must maintain both analog and digital transmission chains simultaneously.

The voluntary migration approach for existing broadcasters acknowledges these economic realities, allowing operators to make business-driven decisions about transition timing based on their individual circumstances, market positions, and strategic priorities. However, this flexibility creates uncertainty about adoption rates and the pace at which digital radio will achieve sufficient scale to deliver transformative benefits.

Consumer Equipment Transition

The success of digital radio ultimately depends on consumer adoption of compatible receivers. The current installed base consists almost entirely of analog-only devices in homes, vehicles, and portable electronics. Digital receiver penetration will depend on pricing, availability, marketing, and perceived value propositions that digital services offer. The automotive sector represents a particularly important channel, as factory-installed receivers in new vehicles can drive adoption, but this requires coordination with automobile manufacturers and potentially regulatory mandates for digital radio capability in new vehicles.

The data channel capability that digital broadcasting enables could support traffic information, weather alerts, and other value-added services that differentiate digital from analog reception. However, realizing these possibilities requires investment in content development, application ecosystems, and user interfaces that make digital advantages tangible and compelling for consumers.

Regulatory Evolution and Adaptation

The convergence of broadcasting with telecommunications and internet services challenges traditional regulatory categories and jurisdictional boundaries. Digital radio services that incorporate data broadcasting, internet streaming, and interactive features blur distinctions between telecommunications, broadcasting, and information services that have historically been regulated under separate frameworks with different legal principles.

The Telecommunications Act, 2023, represents an attempt to create a unified regulatory framework that accommodates technological convergence while maintaining appropriate oversight. However, implementing regulations must address numerous details regarding how traditional broadcasting principles apply to hybrid services that combine linear programming, on-demand content, and interactive applications.

Conclusion

TRAI’s recommendations for digital radio broadcasting policy represent a carefully calibrated approach to modernizing India’s radio broadcasting sector. The simulcast mode framework balances technological advancement with practical transition challenges, while the auction-based spectrum allocation aligns with market-driven resource distribution principles established under the Telecommunications Act, 2023. The recommendations reflect extensive stakeholder consultation and consideration of international experiences, offering a pragmatic pathway for introducing digital broadcasting while protecting consumer interests and maintaining regulatory oversight.

The success of this policy framework will depend on numerous factors including technology standard selection, investment by broadcasters in infrastructure upgrades, consumer adoption of digital receivers, and the development of compelling content and services that leverage digital capabilities. The flexible sunset provisions for analog broadcasting acknowledge the extended transition period likely necessary for achieving widespread digital penetration while maintaining service continuity for existing listeners.

As implementation proceeds, regulatory authorities must remain attentive to emerging challenges including spectrum interference management, content regulation in converged environments, competition concerns, and consumer protection issues. The policy framework establishes foundations for digital radio development, but ongoing regulatory adaptation will be necessary as technology evolves and market dynamics unfold. The coming years will reveal whether India’s approach to digital radio transition successfully balances innovation, competition, and public interest objectives in reshaping the nation’s broadcasting landscape.

References

[1] Morung Express. (2025, October 3). TRAI releases recommendations on digital radio broadcast policy for private broadcasters. Retrieved from https://morungexpress.com/trai-releases-recommendations-on-digital-radio-broadcast-policy-for-private-broadcasters

[2] Government of India. (2023). The Telecommunications Act, 2023 (No. 44 of 2023). The Gazette of India. Retrieved from https://egazette.gov.in/WriteReadData/2023/250880.pdf

[3] Press Information Bureau. (2024). TRAI releases Consultation Paper on “Formulating a Digital Radio Broadcast Policy for private Radio broadcasters”. Retrieved from https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2060201

[4] Communications Today. (2025, October 3). TRAI releases recommendations for digital radio broadcast policy. Retrieved from https://www.communicationstoday.co.in/trai-releases-recommendations-for-digital-radio-broadcast-policy/

[5] The Tribune. (2025, October 3). TRAI recommends auction for allocating frequency bands for digital radio by private broadcasters. Retrieved from https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/broadcast-policy/trai-recommends-auction-for-allocating-frequency-bands-for-digital-radio-by-private-broadcasters

U.S. Imposes Additional 25% Tariff on India Over Russian Oil Purchases: An Analysis of Legal Framework, International Trade Regulations, and Economic Implications

Introduction

In a significant escalation of trade tensions between two major democratic nations, President Donald Trump announced on August 6, 2025, the imposition of an additional 25% tariff on imports from India, effectively doubling the total tariff burden to 50%. This unprecedented trade measure stems from India’s continued procurement and resale of Russian oil despite ongoing geopolitical tensions surrounding the Russia-Ukraine conflict. The decision marks one of the most substantial trade penalties imposed by the United States on a strategic partner and represents a critical juncture in US-India relations, which have historically been characterized by growing economic cooperation and shared democratic values.

The tariff implementation, which became effective on August 27, 2025, has sent shockwaves through international trade circles and raised fundamental questions about the intersection of national security concerns, economic diplomacy, and the legal frameworks governing international commerce. With bilateral trade between the United States and India valued at approximately USD 212.3 billion in 2024, including USD 87.3 billion in US imports from India [1], the ramifications of this decision extend far beyond mere economic calculations, touching upon issues of sovereignty, strategic autonomy, and the evolving architecture of global trade governance.

Legal Foundation of the Tariff Imposition

The International Emergency Economic Powers Act

The legal basis for President Trump’s tariff imposition rests primarily on the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), codified at 50 U.S.C. §§ 1701-1707. This statute, enacted in 1977, grants the President expansive authority to regulate international commerce and financial transactions when facing what the legislation terms an “unusual and extraordinary threat” to national security, foreign policy, or the American economy [2]. The IEEPA represents a carefully calibrated Congressional delegation of power, allowing the executive branch to respond swiftly to emerging international crises while maintaining certain procedural safeguards and reporting requirements.

Under Section 1701(a) of the IEEPA, the President may exercise this authority only after declaring a national emergency pursuant to the National Emergencies Act. The statute specifically empowers the executive to “investigate, regulate, or prohibit” any transactions in foreign exchange, transfers of credit or payments between financial institutions, and the importation or exportation of currency or securities. Most relevant to the current situation, subsection 1702(a)(1)(B) explicitly authorizes the President to “regulate or prohibit” imports when such action is deemed necessary to address the declared emergency.

Executive Order 14257 and the Reciprocal Tariff Framework

The immediate legal instrument implementing the tariff on India derives from Executive Order 14257, titled “Regulating Imports With a Reciprocal Tariff To Rectify Trade Practices That Contribute to Large and Persistent Annual United States Goods Trade Deficits,” issued on April 2, 2025 [3]. This executive order established a comprehensive framework for what the administration termed “reciprocal tariffs,” designed to address what it characterized as unfair trade practices and persistent trade imbalances that, in the President’s determination, constituted a national emergency.

Executive Order 14257 declared that conditions reflected in large and persistent annual United States goods trade deficits constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and economy of the United States. The order established a baseline 10% tariff on imports from most trading partners, with provisions for higher country-specific rates based on various economic and security considerations. Critically, the order included Annex II, which specified certain exempt categories of goods deemed essential to American pharmaceutical production, electronics manufacturing, and critical mineral supply chains.

The August 2025 Presidential Determination on India

On August 6, 2025, President Trump issued a separate executive determination specifically addressing India’s role in the Russian oil trade. Titled “Addressing Threats to the United States by the Government of the Russian Federation,” the order invoked both the IEEPA and the framework established under Executive Order 14257 to justify the additional 25% tariff on Indian imports. The White House fact sheet accompanying the decision stated that the measure was necessary because India’s “direct or indirect importation of Russian Federation oil” enables funding of Russia’s military operations in Ukraine, thereby undermining U.S. efforts to counter these activities and presenting a threat to American national security interests.

The determination emphasized that India’s practice of purchasing Russian crude oil at discounted rates and subsequently refining and reselling petroleum products to international markets, including potentially to American consumers, created what the administration characterized as a sanctions evasion mechanism. This characterization proved controversial, as India’s oil trade with Russia remained technically legal under existing international law, even as it complicated Western efforts to economically isolate Moscow.

Regulatory Framework Governing International Tariffs

Harmonized Tariff Schedule and Classification

The implementation of tariffs on Indian goods operates within the broader framework of the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS), which provides the nomenclature and classification system for all goods entering American commerce. As part of this policy, the U.S. imposes an additional 25% tariff on India, applied as an ad valorem duty calculated as a percentage of the declared customs value of imported merchandise. This duty supplements, rather than replaces, any existing tariffs already applicable to specific product categories under normal trade relations.

The United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP), operating under the authority of Title 19 of the United States Code, bears responsibility for collecting these duties and enforcing compliance. Section 1500 of Title 19 establishes the procedures for appraising imported merchandise and determining the appropriate tariff classification. The CBP’s implementing regulations, found in Title 19 of the Code of Federal Regulations, provide detailed guidance on valuation methods, country of origin determinations, and the application of special tariff programs.

Exemptions and Excluded Categories

Recognizing that certain imports serve critical national interests despite broader trade tensions, the tariff order incorporates specific exemptions for goods listed in Annex II of Executive Order 14257. These exemptions reflect a pragmatic acknowledgment that American manufacturing and pharmaceutical sectors depend on certain mineral and energy resources that would be difficult or prohibitively expensive to source from alternative suppliers in the short term.

The exempt categories include various rare earth elements, critical minerals used in semiconductor manufacturing, certain pharmaceutical active ingredients, and specific energy resources. The Department of Commerce, in consultation with other agencies, maintains the authority to modify this exemption list through periodic reviews. This mechanism allows the administration to balance punitive trade measures against the practical realities of global supply chain dependencies.

The World Trade Organization Framework and International Trade Law

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Obligations

The imposition of country-specific tariffs by the United States raises complex questions under the World Trade Organization (WTO) legal framework, particularly regarding the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Article I of the GATT enshrines the principle of Most Favored Nation (MFN) treatment, requiring WTO members to accord products from any member nation treatment no less favorable than that given to products from any other country. This fundamental principle aims to prevent discriminatory trade practices and ensure a level playing field in international commerce [5].

However, the GATT includes several exceptions that potentially provide legal cover for the American tariff measures. Article XXI, known as the security exception, permits members to take actions they consider “necessary for the protection of its essential security interests” relating to fissionable materials, traffic in arms, or actions “taken in time of war or other emergency in international relations.” The interpretation and application of Article XXI has generated considerable controversy within the WTO, with members disagreeing about whether such determinations are self-judging or subject to review by dispute settlement panels.

Previous WTO Disputes Involving Security Exceptions

The WTO dispute settlement mechanism has only recently begun to grapple seriously with security exception claims. In the landmark case of Russia – Measures Concerning Traffic in Transit (DS512), a panel established in 2019 determined that Article XXI’s security exception is not entirely self-judging, though panels should exercise restraint in reviewing a member’s characterization of its essential security interests [6]. The panel held that certain objective requirements must be met, particularly that the disputed measures must relate to one of the enumerated circumstances in Article XXI(b) and that the nexus between the measure and the stated security concern must be plausible.

This precedent suggests that while the United States enjoys considerable discretion in defining its security interests, India could potentially challenge the tariffs at the WTO by arguing that the connection between oil trade and American security interests fails to meet even this deferential standard. However, the practical utility of such a challenge remains uncertain given the WTO’s ongoing crisis surrounding its Appellate Body, which has been non-functional since December 2019 due to American blocking of new appointments.

India’s Legal Position and Response Options

Sovereignty and Non-Alignment Principles