Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

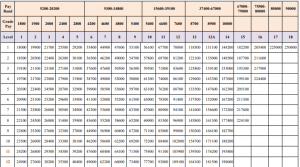

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

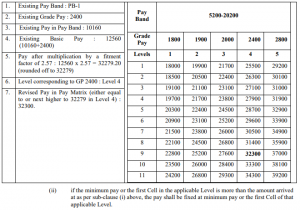

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

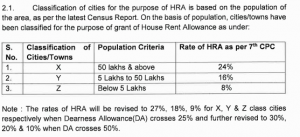

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

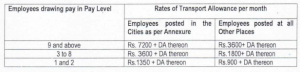

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

IBBI’s Proposed CIRP Amendments: Strengthening Transparency and Integrity in India’s Insolvency Resolution Framework

Introduction

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India has recently invited public comments on significant amendments to the corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP), marking another evolutionary step in India’s insolvency regime. These proposed changes, announced in August 2025, reflect the regulatory body’s commitment to refining the framework that has transformed India’s approach to corporate distress since the enactment of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code in 2016. The CIRP amendments 2025 focus on three critical areas: recording deliberations of the Committee of Creditors regarding resolution applicant eligibility, enhancing disclosure requirements for resolution plans, and mandating electronic platforms for invitation and submission of resolution plans. These changes emerge from a confluence of judicial pronouncements, stakeholder feedback, and practical experiences accumulated over years of implementation, and they represent a parliamentary committee recommendation following the success of similar requirements in the liquidation process.

The significance of these CIRP amendments extends beyond procedural modifications. They address fundamental concerns about transparency, accountability, and fairness that have emerged through the resolution of hundreds of corporate insolvencies since the Code’s implementation. By requiring formal documentation of Committee of Creditors’ deliberations and expanding disclosure obligations, the regulatory framework seeks to minimize litigation, prevent potential abuse, and ensure that the insolvency resolution process achieves its twin objectives of maximizing asset value while maintaining the integrity of the corporate resolution mechanism. The timing of these amendments is particularly relevant as India continues to refine its insolvency ecosystem, balancing the need for swift resolution with safeguards against misuse of the process.

Understanding the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process Framework

The corporate insolvency resolution process operates as the cornerstone of India’s insolvency regime, established through the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016. This time-bound process, typically limited to 330 days including judicial processes [1], provides a structured mechanism for resolving corporate distress while preserving the corporate debtor as a going concern. The process commences upon admission of an application filed by financial creditors, operational creditors, or the corporate debtor itself, triggering an automatic moratorium that protects the debtor from legal proceedings and enforcement actions during the resolution period.

Once the process begins, an interim resolution professional takes control of the corporate debtor’s management, replacing the existing board of directors. The resolution professional’s responsibilities encompass managing the debtor’s operations, preserving and protecting its assets, constituting the Committee of Creditors, and facilitating the submission and approval of resolution plans. The Committee of Creditors, comprising financial creditors with voting rights proportional to their debt, becomes the primary decision-making body during the resolution process. This committee evaluates resolution plans submitted by prospective applicants and approves a plan that offers the best prospects for maximizing asset value while satisfying creditors’ claims.

The legislative framework governing this process extends beyond the primary Code to encompass detailed regulations issued by the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India. The IBBI (Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2016, supplemented by multiple amendments in subsequent years, provide operational guidelines covering every aspect of the resolution process. These regulations specify procedures for conducting the process, requirements for resolution professionals, formats for various submissions, and standards for resolution plans. The regulatory framework has evolved continuously since 2016, with the Board issuing amendments in 2025 alone that address various aspects including part-wise resolution of corporate debtors, homebuyer participation as resolution applicants, and enhanced disclosure requirements for resolution plans.

The Committee of Creditors and Decision-Making Authority

The Committee of Creditors represents one of the most distinctive features of India’s insolvency regime, concentrating decision-making authority in the hands of financial creditors who hold the largest economic stake in the corporate debtor’s revival. The composition and functioning of this committee have been subjects of extensive judicial interpretation, particularly regarding the extent of its powers and the limits on judicial interference with its commercial decisions. The Supreme Court of India, in the landmark judgment of Committee of Creditors of Essar Steel India Limited v. Satish Kumar Gupta [2], articulated the foundational principle that the Committee of Creditors possesses wide discretion in commercial matters related to the resolution process, including the evaluation and approval of resolution plans.

The Essar Steel judgment clarified that the Committee of Creditors operates with substantial autonomy in assessing resolution plans based on commercial considerations, and courts should exercise restraint in interfering with these decisions unless they violate statutory provisions or suffer from patent illegality. This judicial deference recognizes that financial creditors, having the maximum stake in the outcome, are best positioned to evaluate competing resolution proposals and determine which plan maximizes value for all stakeholders. The judgment emphasized that the Code’s architecture deliberately places commercial wisdom with financial creditors rather than operational creditors or the adjudicating authority, reflecting a policy choice to prioritize the interests of those who advanced credit to the corporate debtor.

However, the Committee’s authority, while extensive, operates within defined boundaries. The Committee cannot take decisions that violate mandatory provisions of the Code or regulations, discriminate among creditors within the same class, or approve plans that fail to meet statutory requirements. The resolution plan must satisfy multiple conditions specified in the Code, including payment of insolvency resolution process costs, provision for operational creditors, and compliance with other applicable laws. Furthermore, the Committee must ensure that resolution applicants satisfy eligibility criteria specified in the Code, particularly those outlined in Section 29A, which disqualifies certain categories of persons from submitting resolution plans.

The proposed amendments to CIRP 2025 seek to strengthen the Committee’s decision-making process by requiring formal documentation of deliberations regarding resolution applicant eligibility. This requirement addresses concerns that have emerged through practical experience, where disputes about applicant eligibility have led to protracted litigation and delayed resolution. By mandating that the Committee record its deliberations in meeting minutes, the CIRP amendments aim to create a transparent record demonstrating that the Committee properly considered each applicant’s eligibility before approving their resolution plan. This documentation requirement serves multiple purposes: it encourages thorough discussion of eligibility issues, provides a basis for reviewing the Committee’s decision if challenged, and demonstrates compliance with statutory requirements regarding applicant eligibility.

Section 29A: Eligibility Criteria for Resolution Applicants

Section 29A of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code establishes comprehensive disqualifications that prevent certain categories of persons from submitting resolution plans, representing one of the Code’s most critical safeguards against misuse of the insolvency process. Introduced through the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Amendment) Act, 2018, this provision emerged in response to concerns that the original framework allowed promoters and related parties who contributed to the corporate debtor’s distress to regain control through the resolution process. The section’s disqualifications extend to various categories including undischarged insolvents, wilful defaulters, persons with non-performing accounts, persons convicted of specified offenses, persons prohibited from trading in securities, and persons disqualified from acting as directors.

The scope of Section 29A extends beyond the resolution applicant to encompass persons acting jointly or in concert with the applicant, preventing circumvention through related party structures. The provision disqualifies not only individuals falling within specified categories but also entities where such individuals hold significant ownership or control. For instance, if a person is a wilful defaulter, not only is that person disqualified, but any entity where that person holds beneficial interest exceeding specified thresholds also becomes ineligible to submit resolution plans. This comprehensive approach prevents sophisticated structures designed to bypass eligibility requirements while nominally complying with the provision’s letter.

The interpretation and application of Section 29A have generated substantial jurisprudence, with courts addressing questions about the provision’s scope, timing of eligibility determination, and relationship with other Code provisions. The provision’s language requires resolution applicants to submit affidavits confirming their eligibility under Section 29A along with their resolution plans, as specified in Section 30(2) of the Code. This requirement places an initial burden on resolution applicants to conduct due diligence regarding their eligibility and certify compliance with all disqualification criteria. However, the Committee of Creditors retains responsibility for independently verifying applicant eligibility before approving any resolution plan, as approval of a plan submitted by an ineligible person would violate mandatory statutory provisions and render the approval void.

The IBBI proposed CIRP amendments recognize that despite existing requirements for eligibility affidavits, disputes regarding applicant eligibility continue to arise, often leading to litigation that delays or derails resolution processes. The current framework lacks specific provisions requiring the Committee of Creditors to formally document its consideration of eligibility issues, creating situations where committees approve plans without thoroughly examining applicant eligibility or maintaining clear records of their deliberations on these matters. This gap has resulted in cases where approved resolution plans were subsequently challenged based on applicant ineligibility, leading courts to remit matters back to the Committee for reconsideration or, in some instances, to reject approved plans altogether.

To address these concerns, the proposed amendments to CIRP introduce requirements for enhanced disclosure by resolution applicants, specifically mandating submission of statements regarding beneficial ownership and affidavits confirming eligibility. The beneficial ownership statement must identify all natural persons who ultimately own or control the prospective resolution applicant, including details of the shareholding structure and jurisdiction of each entity in the ownership chain. This requirement aims to prevent situations where ineligible persons hide behind complex corporate structures to circumvent Section 29A disqualifications. By requiring full transparency regarding beneficial ownership, the amendments enable the Committee of Creditors to conduct thorough due diligence and identify potential eligibility issues before approving resolution plans.

Judicial Pronouncements Shaping CIRP Practice

The evolution of India’s insolvency framework has been substantially influenced by judicial interpretations that have clarified ambiguities, resolved conflicts, and established principles governing various aspects of the resolution process. The Supreme Court’s role has been particularly significant, with landmark judgments addressing fundamental questions about the Code’s architecture, the Committee of Creditors’ powers, eligibility of resolution applicants, and the scope of judicial review over commercial decisions made during the resolution process.

Beyond the Essar Steel judgment, which established the Committee of Creditors’ primacy in commercial decision-making, courts have addressed numerous other critical issues. In Swiss Ribbons Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India [3], the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of various Code provisions, including Section 29A’s disqualifications, rejecting challenges that these provisions violated constitutional rights or operated retrospectively. The judgment emphasized that Section 29A serves a legitimate purpose of preventing persons responsible for or connected with corporate debtor’s default from regaining control through the resolution process, and that the provision’s disqualifications represent reasonable restrictions necessary to achieve the Code’s objectives.

Courts have also addressed procedural aspects of the resolution process, including timelines, withdrawal of applications, and the relationship between settlement negotiations and insolvency proceedings. Recent Supreme Court pronouncements have clarified that applications for withdrawal under Section 12A of the Code can be filed even before constitution of the Committee of Creditors, provided settlements satisfy statutory requirements and receive necessary approvals [4]. These judgments reflect judicial recognition that while the Code establishes a time-bound process, flexibility remains necessary to accommodate genuine settlements that serve creditors’ interests better than continued insolvency proceedings.

The jurisprudence surrounding Section 29A has been particularly rich, with courts examining various disqualification criteria and their application to different factual scenarios. Courts have held that Section 29A disqualifications must be determined as of the date of resolution plan submission, and that subsequent events removing disqualifications do not render previously ineligible persons eligible. Similarly, courts have addressed questions about whether guarantors of corporate debtors’ debts are disqualified under Section 29A(h), which bars persons whose account has been classified as non-performing asset, concluding that guarantors generally fall within this disqualification when their accounts are classified as non-performing.

Judicial pronouncements have also emphasized the importance of maintaining process integrity and preventing abuse of the insolvency framework. Courts have intervened to prevent fraudulent conduct, unauthorized asset disposals, and violations of moratorium provisions, demonstrating that while the Committee of Creditors enjoys wide discretion in commercial matters, this discretion does not extend to tolerating illegal conduct or approving plans that violate mandatory statutory provisions. These judgments have shaped the practical implementation of the resolution process, establishing guardrails that balance efficiency with procedural fairness and legal compliance.

The proposed CIRP amendments draw extensively from lessons learned through judicial proceedings, incorporating requirements designed to address issues that have generated litigation and created uncertainty. The requirement to record Committee deliberations on eligibility reflects judicial emphasis on transparent decision-making and proper consideration of statutory requirements. Similarly, enhanced disclosure requirements for resolution applicants respond to judicial observations about the need for complete information regarding applicant structures and beneficial ownership to enable proper evaluation of Section 29A compliance.

Recording Committee Deliberations: Transparency and Accountability

The requirement to record Committee of Creditors’ deliberations regarding resolution applicant eligibility represents perhaps the most significant procedural innovation in the proposed CIRP amendments. Currently, the IBBI regulations require the resolution professional to prepare minutes of Committee meetings, documenting decisions taken and voting patterns. However, these regulations do not specifically mandate detailed recording of discussions, arguments, evidence considered, or reasoning underlying decisions regarding resolution applicant eligibility. The proposed amendments to CIRP seek to address this gap by requiring that the Committee’s deliberations on eligibility be formally documented in meeting minutes, creating a comprehensive record of how the Committee assessed compliance with Section 29A disqualifications.

This documentation requirement serves multiple interrelated purposes that strengthen the resolution process’s integrity and efficiency. First, it encourages thorough and rigorous consideration of eligibility issues by making the Committee’s analysis transparent and subject to review. When Committee members know their deliberations will be recorded and potentially scrutinized, they are more likely to carefully examine eligibility questions, seek necessary clarifications from resolution applicants, and ensure that decisions rest on proper evaluation of all relevant factors. This discipline in deliberation reduces the risk of cursory or superficial examination of eligibility issues that might lead to approval of plans submitted by ineligible persons.

Second, formal recording of deliberations creates evidentiary basis for defending Committee decisions if subsequently challenged. When resolution plans are approved, dissatisfied stakeholders sometimes file appeals challenging the plan’s validity, often raising questions about resolution applicant eligibility. In such proceedings, having detailed minutes documenting the Committee’s consideration of eligibility issues provides crucial evidence demonstrating that the Committee properly discharged its statutory responsibilities. Courts reviewing challenged decisions can examine the recorded deliberations to determine whether the Committee reasonably concluded that the resolution applicant satisfied Section 29A requirements, or whether the decision suffered from non-application of mind or failure to consider relevant factors.

Third, documentation requirements promote consistency and procedural fairness by ensuring that all resolution applicants receive equal consideration regarding eligibility issues. When the Committee must record its deliberations for each applicant, it becomes more difficult to apply different standards to different applicants or to dismiss eligibility concerns for favored applicants while rigorously examining others. The requirement to document deliberations thus serves as a procedural safeguard ensuring that eligibility determinations rest on objective assessment of statutory criteria rather than subjective preferences or improper considerations.

The practical implementation of this requirement will necessitate changes in how Committees conduct meetings and resolution professionals prepare minutes. Rather than simply recording votes and decisions, meeting minutes must now capture substantive discussions about eligibility issues, including concerns raised by Committee members, information provided by resolution applicants, expert opinions or legal advice considered, and the reasoning underlying the Committee’s ultimate conclusion regarding each applicant’s eligibility. Resolution professionals will need to ensure that adequate time is allocated in Committee meetings for thorough discussion of eligibility issues, and that minutes accurately reflect these deliberations while maintaining appropriate confidentiality regarding sensitive commercial information.

The documentation requirement also has implications for resolution applicants, who must anticipate that eligibility issues will receive careful scrutiny and be prepared to provide comprehensive information supporting their compliance with Section 29A requirements. Applicants may need to provide detailed submissions addressing each disqualification criterion, demonstrating through documentary evidence that neither they nor persons acting jointly or in concert fall within any disqualified category. This increased emphasis on eligibility verification may lengthen the evaluation process but should ultimately reduce post-approval challenges and enhance confidence in the integrity of approved resolution plans.

Enhanced Disclosure Requirements and Beneficial Ownership

The proposed amendments to CIRP introduce requirements for resolution applicants to file statements of beneficial ownership along with their resolution plans, addressing concerns about transparency regarding applicant structures and ultimate ownership. The concept of beneficial ownership has gained increasing prominence in corporate governance and regulatory frameworks worldwide, recognizing that legal ownership structures often obscure the natural persons who ultimately control or benefit from corporate entities. In the insolvency context, understanding beneficial ownership becomes critical for assessing Section 29A eligibility, as disqualifications extend to persons acting jointly or in concert with resolution applicants and entities where disqualified persons hold significant beneficial interest.

The beneficial ownership disclosure requirement mandates that resolution applicants provide information identifying all natural persons who ultimately own or control the applicant entity. This includes details of the complete shareholding structure, identifying each layer of ownership from the applicant entity through intermediate holding companies to ultimate individual shareholders. For each entity in the ownership chain, applicants must disclose the jurisdiction of incorporation, shareholding percentages, and any special rights or control mechanisms that affect actual control despite nominal shareholding. This comprehensive disclosure enables the Committee of Creditors to trace ownership through multiple layers and identify whether any disqualified persons hold beneficial interest in the resolution applicant.

The requirement responds to practical challenges that have emerged where resolution applicants have been structured to conceal the involvement of persons potentially disqualified under Section 29A. Complex corporate structures involving multiple jurisdictions, nominee arrangements, trust structures, and special purpose vehicles can obscure beneficial ownership, making it difficult for Committees to verify eligibility based solely on information provided in standard resolution plan formats. By mandating explicit beneficial ownership disclosure, the amendments shift responsibility to resolution applicants to transparently reveal their ownership structures, facilitating proper due diligence by the Committee.

The beneficial ownership statement must identify specific natural persons who qualify as beneficial owners under applicable definitions, which typically include persons holding significant ownership interest or exercising significant control over the entity. Significant ownership interest is generally defined as holding specified percentages of shares or voting rights, while significant control encompasses ability to appoint majority of directors, control management decisions, or exercise influence through agreements or arrangements. Resolution applicants must identify all individuals meeting these criteria at each level of their corporate structure, ensuring that the Committee can assess whether any such individuals fall within Section 29A disqualifications.

In addition to beneficial ownership statements, the amendments require resolution applicants to file affidavits confirming their eligibility under Section 29A. While Section 30(2) of the Code already requires such affidavits, the proposed CIRP amendments appear to strengthen this requirement, possibly by mandating more detailed affidavits addressing each disqualification criterion specifically. The affidavit serves as a formal certification by the resolution applicant that neither the applicant nor any person acting jointly or in concert falls within any disqualified category, and that all information provided regarding ownership, control, and related party relationships is accurate and complete.

These disclosure requirements create legal consequences for resolution applicants who provide false or misleading information. Submission of false affidavits can expose applicants to criminal liability for perjury, while material misrepresentation regarding beneficial ownership or eligibility can form grounds for rejecting resolution plans or canceling approved plans. The enhanced disclosure framework thus creates strong incentives for resolution applicants to conduct thorough internal due diligence regarding their eligibility and to provide complete and accurate information to the Committee. This shift toward greater applicant responsibility for eligibility verification should reduce situations where ineligible persons submit plans based on incomplete or misleading disclosures.

Electronic Platforms and Process Digitization

The proposed CIRP amendments include provisions requiring invitation and submission of resolution plans through electronic platforms, representing a significant step toward digitization of the insolvency resolution process. This requirement follows successful implementation of similar systems in the liquidation process, where electronic platforms have improved transparency, reduced processing time, and created comprehensive digital records of proceedings. The extension of electronic platforms to the resolution plan submission stage reflects broader governmental initiatives toward digital governance and paperless processes across regulatory domains.

Electronic platforms for resolution plan submission offer multiple advantages over traditional paper-based processes. They enable standardized data collection, ensuring that all resolution applicants provide information in consistent formats that facilitate comparison and analysis. Digital submission eliminates logistical challenges associated with physical document handling, particularly when multiple applicants submit lengthy plans with numerous annexures and supporting documents. Electronic platforms also create audit trails documenting when plans were submitted, what modifications were made, and how different versions compare, enhancing transparency and accountability throughout the evaluation process.

The requirement for electronic submission through designated platforms will necessitate development of appropriate technological infrastructure by the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India. The Board will need to establish secure platforms capable of handling large document volumes, maintaining confidentiality of sensitive commercial information, providing appropriate access controls for resolution professionals and Committee members, and generating reports and analytics to support decision-making. The platform should accommodate various document formats, allow for secure communication between resolution applicants and resolution professionals, and maintain comprehensive records meeting evidentiary standards for potential litigation.

For resolution professionals and Committees of Creditors, electronic platforms promise to streamline the plan evaluation process significantly. Rather than reviewing paper documents spread across multiple volumes, Committee members can access digital plans through user-friendly interfaces that allow searching, comparison across different plans, and tracking of revisions. Electronic platforms can incorporate analytical tools that automatically extract key financial parameters, compare payment terms, and flag potential issues requiring closer examination. These capabilities should enable more efficient and thorough evaluation of resolution plans, particularly in cases involving multiple competing proposals.

Resolution applicants will need to adapt their plan preparation processes to accommodate electronic submission requirements. This includes preparing documents in specified electronic formats, organizing information according to platform requirements, and potentially using digital signatures or other authentication mechanisms to verify submitted materials. While electronic submission may initially present learning curves for some applicants, the standardization and efficiency gains should ultimately simplify the submission process compared to preparing multiple physical copies of voluminous plan documents.

The electronic platform requirement also facilitates compliance monitoring and regulatory oversight by the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India. The Board can access standardized data from all corporate insolvency resolution processes, enabling analysis of trends, identification of systemic issues, and evidence-based policymaking. Electronic records allow the Board to monitor compliance with timelines, track outcomes across different categories of corporate debtors, and evaluate the effectiveness of regulatory requirements. This data-driven approach to regulation should support continuous refinement of the insolvency framework based on empirical evidence rather than anecdotal observations.

Implications for Stakeholders and Future Outlook

The IBBI’s Proposed CIRP Amendments carry significant implications for all participants in the corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP), requiring adjustments to established practices and creating new compliance obligations. For resolution professionals, the amendments expand responsibilities regarding documentation, verification, and platform management. Resolution professionals must ensure that Committee meetings allocate sufficient time for thorough discussion of eligibility issues and that minutes accurately capture these deliberations while maintaining appropriate confidentiality. They must also manage the electronic platform for plan submission, verify that applicants have provided required beneficial ownership statements and affidavits, and facilitate Committee access to all submitted materials.

Financial creditors serving on Committees of Creditors will face expectations for more active engagement with eligibility issues. Rather than deferring to resolution professional recommendations or accepting applicant representations at face value, Committee members should conduct their own due diligence regarding eligibility, raise questions about concerning aspects of applicant structures or histories, and ensure that deliberations adequately address all relevant factors. The requirement to record deliberations creates accountability for Committee members’ contributions to eligibility discussions, potentially increasing their diligence in reviewing applicant credentials.

Resolution applicants confront heightened disclosure obligations and increased scrutiny of their eligibility credentials. Preparing beneficial ownership statements and detailed eligibility affidavits will require substantial effort, particularly for applicants with complex corporate structures spanning multiple jurisdictions. Applicants must conduct thorough internal due diligence to identify all persons who might be considered to be acting jointly or in concert and to verify that none of these persons falls within Section 29A disqualifications. The enhanced transparency requirements may deter some potential applicants whose eligibility status is uncertain or whose ownership structures would raise concerns if fully disclosed.

For the broader insolvency ecosystem, these amendments signal continued evolution toward greater transparency, formalization, and digital integration. The amendments reflect lessons learned from several years of implementation experience, incorporating practical solutions to recurring problems. They demonstrate the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India’s commitment to evidence-based regulation that responds to stakeholder feedback and judicial pronouncements while advancing the Code’s fundamental objectives of maximizing value and preserving viable businesses.

Looking forward, successful implementation of these amendments will depend on several factors. The Board must develop robust electronic platforms that function reliably under high transaction volumes while maintaining security and confidentiality. Resolution professionals require training on new documentation requirements and platform operation. Committee members need guidance on conducting and recording eligibility deliberations. Resolution applicants should receive clear instructions regarding beneficial ownership disclosure requirements and affidavit contents. Stakeholder education and capacity building will be essential to ensure smooth transition to the amended framework.

The CIRP amendments also open possibilities for further evolution of India’s insolvency regime. Experience with electronic platforms in plan submission may inform broader digitization of insolvency processes, including claims verification, asset valuation, and distribution calculations. Enhanced beneficial ownership disclosure requirements established in the insolvency context might influence beneficial ownership reporting in other regulatory domains. Documentation of Committee deliberations could extend to other aspects of decision-making beyond eligibility determination, creating comprehensive records supporting all key decisions during the resolution process.

Conclusion

The proposed amendments to the corporate insolvency resolution (CIRP) process regulations represent thoughtful refinements addressing practical challenges identified through implementation experience. By requiring documentation of Committee deliberations on resolution applicant eligibility, mandating enhanced disclosure of beneficial ownership, and establishing electronic platforms for plan submission, the CIRP amendments strengthen transparency, reduce litigation risk, and modernize process infrastructure. These changes align with broader global trends toward greater transparency in insolvency proceedings and beneficial ownership reporting while respecting the distinctive architecture of India’s insolvency framework.

The CIRP amendments reflect careful balancing of competing considerations. They impose additional procedural requirements that may extend resolution timelines and increase compliance burdens, but these costs appear justified by benefits of reduced litigation, enhanced confidence in approved plans, and improved decision-making quality. The amendments preserve the Committee of Creditors’ primacy in commercial decision-making while creating accountability mechanisms ensuring that this discretion is exercised responsibly and transparently. They leverage technology to improve process efficiency without sacrificing the flexibility necessary to accommodate diverse circumstances across different corporate insolvencies.

As these CIRP amendments move from proposal to implementation, their success will ultimately be measured by whether they achieve intended objectives without creating unintended obstacles. Stakeholder comments during the public consultation period will provide valuable input for refining proposed provisions before finalization. The insolvency ecosystem’s response—how effectively participants adapt practices to comply with new requirements—will determine whether the amendments deliver promised improvements. With appropriate implementation support and continued monitoring of outcomes, these amendments should advance India’s insolvency framework toward greater maturity, transparency, and effectiveness in achieving the twin goals of maximizing value and preserving viable businesses facing financial distress.

References

[1] Supreme Court of India. (2025). Committee of Creditors of Essar vs. Satish. 2025 INSC 124.

[2] Supreme Court of India. (2019). Committee of Creditors of Essar Steel India Limited v. Satish Kumar Gupta & Ors. Civil Appeal No. 8766-67 of 2018. Available at: https://ibclaw.in/summary-of-landmark-judgment-of-supreme-court-in-committee-of-creditors-of-essar-steel-india-limited-vs-satish-kumar-gupta-ors-under-ibc/

[3] Supreme Court of India. (2019). Swiss Ribbons Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India. Civil Appeal No. 99 of 2018.

[4] Supreme Court of India. (2023). Withdrawal applications under Section 12A IBC. Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/ibc-application-under-section-12a-for-withdrawal-of-cirp-is-maintainable-prior-to-constitution-of-coc-supreme-court-225026

[5] Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India. (2016). IBBI (Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2016. Available at: https://ibbi.gov.in

[6] Government of India. (2016). The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (Act No. 31 of 2016). Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15479/1/the_insolvency_and_bankruptcy_code,_2016.pdf

[7] Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India. (2025). IBBI (Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) (Fifth Amendment) Regulations, 2025. Available at: https://indiacorplaw.in/2025/07/24/amendments-to-the-ibbi-regulations-on-corporate-insolvency-the-future-of-transparency/

[8] IBC Laws. (2024). Section 29A of IBC – Persons not eligible to be resolution applicant. Available at: https://ibclaw.in/section-29a-persons-not-eligible-to-be-resolution-applicant/

[9] ELP Law. (2024). Recent landmark judgments of the Supreme Court under IBC. Available at: https://elplaw.in/leadership/recent-landmark-judgments-of-the-supreme-court-under-ibc/

India-EAEU Free Trade Agreement: A Comprehensive Analysis of Legal Framework and Economic Implications

Introduction

The signing of the Terms of Reference between India and the Eurasian Economic Union in September 2025 represents a watershed moment in India’s trade diplomacy. India-EAEU agreement to commence negotiations for a free trade agreement marks India’s strategic pivot towards diversifying its trade partnerships beyond traditional Western markets. The Eurasian Economic Union, comprising Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and the Russian Federation, presents a combined market with a GDP of USD 6.5 trillion and offers Indian exporters unprecedented access to a largely untapped regional bloc.[1]

The ceremonial signing took place in Moscow, where Ajay Bhadoo, Additional Secretary of India’s Department of Commerce, and Mikhail Cherekaev, Deputy Director of the Trade Policy Department at the Eurasian Economic Commission, formalized the procedural framework that will govern the negotiation process. This development comes at a time when bilateral trade between India and the EAEU reached USD 69 billion in 2024, reflecting a seven percent increase from the previous year.[2] The momentum behind this initiative underscores both parties’ commitment to establishing a robust institutional mechanism for long-term economic cooperation.

Understanding Free Trade Agreements in India’s Trade Architecture

Free trade agreements have become instrumental tools in India’s economic strategy to integrate with the global economy while protecting domestic interests. The fundamental distinction between various types of trade agreements helps contextualize the significance of the India-EAEU negotiations. A Free Trade Agreement eliminates tariffs on items covering substantial bilateral trade between partner countries, while each nation maintains its individual tariff structure for non-members. This differs from Preferential Trade Agreements, which provide preferential access by reducing tariffs on select products, and Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreements or Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements, which encompass goods, services, investment, and trade facilitation measures.[3]

India’s approach to free trade agreements has evolved significantly over the past three decades. The country has moved from protective trade policies to a more liberalized regime that seeks to balance domestic industry protection with the benefits of global integration. The legal architecture supporting this transformation provides the foundation for negotiating and implementing international trade agreements like the proposed India-EAEU FTA.

Legal Framework Governing Trade Agreements in India

The Foreign Trade (Development and Regulation) Act, 1992

The cornerstone of India’s trade regulation framework is the Foreign Trade (Development and Regulation) Act, 1992, which came into force on August 7, 1992. This legislation replaced the outdated Imports and Exports (Control) Act, 1947, reflecting India’s transition toward economic liberalization. The Act establishes the legal basis for the development and regulation of foreign trade by facilitating imports into India and augmenting exports from the country.[4]

The Act empowers the Central Government to formulate and announce the Foreign Trade Policy, which is typically released every five years and contains provisions for promoting exports, regulating imports, and implementing trade agreements. Under Section 5 of the Act, the Central Government is authorized to make provisions for facilitating and regulating foreign trade through various measures including the prohibition or restriction of imports or exports, quality control and inspection requirements, and the registration of exporters and importers.

The procedural aspects of trade agreement negotiations fall within the purview of this Act, as it provides the Director General of Foreign Trade with powers to issue licenses, permissions, and other authorizations necessary for implementing trade facilitation measures. The Act’s flexibility allows the government to incorporate obligations arising from international trade agreements into domestic trade policy without requiring separate legislative approval for each agreement.

Constitutional Framework and Treaty-Making Powers

India’s Constitution does not explicitly delineate the treaty-making process, but Article 73 vests executive power in the Union Government to conduct international relations and enter into treaties. The legislative competence to implement international agreements derives from Entry 14 of List I (Union List) of the Seventh Schedule, which grants Parliament exclusive authority over matters relating to “entering into treaties and agreements with foreign countries and implementing of treaties, agreements and conventions with foreign countries.”

This constitutional architecture means that while the executive branch possesses the power to negotiate and sign international trade agreements, the implementation of such agreements often requires parliamentary approval, particularly when the agreement necessitates changes to existing domestic legislation. However, for trade agreements that fall within the ambit of executive action and do not contradict existing laws, the government can proceed with implementation through executive orders and policy notifications.

Customs Act, 1962 and Tariff Regulations

The Customs Act, 1962, works in conjunction with the Foreign Trade (Development and Regulation) Act to operationalize trade agreements. Section 25 of the Customs Act empowers the Central Government to grant exemptions from customs duties through notifications, which becomes the mechanism for implementing tariff concessions agreed upon in free trade agreements. The Customs Tariff Act, 1975, provides the framework for imposing duties on imports and exports and allows for preferential tariff treatment under trade agreements.[5]

When India enters into a free trade agreement, the tariff concessions are typically implemented through notifications under Section 25 of the Customs Act. These notifications specify the rules of origin, which determine whether imported goods qualify for preferential treatment under the agreement. The rules of origin are crucial in preventing trade deflection, where goods from non-member countries might be routed through member countries to benefit from reduced tariffs.

The Eurasian Economic Union: Structure and Significance

The Eurasian Economic Union represents a unique regional integration project that emerged from the post-Soviet space. Established through the Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Union signed on May 29, 2014, the EAEU came into force on January 1, 2015. The union’s foundational treaty created a single market among its member states, characterized by the free movement of goods, services, capital, and labor. The EAEU’s institutional framework includes the Supreme Eurasian Economic Council, the Eurasian Economic Commission, and the Court of the Eurasian Economic Union.

For India, engaging with the EAEU offers several strategic advantages beyond immediate trade benefits. The geographical expanse of the EAEU provides India with land-based connectivity to European markets through the International North-South Transport Corridor, potentially reducing logistics costs and transit times. Additionally, the EAEU’s close relationship with China through parallel Belt and Road initiatives means that India’s engagement can serve broader geopolitical objectives of maintaining balanced relationships in the Eurasian space.

The combined GDP of USD 6.5 trillion and a population exceeding 180 million people make the EAEU an attractive market for Indian goods and services. Russia, as the largest economy within the union, accounts for approximately 85 percent of the EAEU’s GDP, making bilateral India-Russia trade a significant component of overall India-EAEU economic relations. The existing bilateral trade of USD 69 billion in 2024 provides a substantial foundation upon which a free trade agreement can build momentum.[2]

Terms of Reference: Establishing the Negotiating Framework

The Terms of Reference signed in September 2025 establish both the procedural and organizational basis for conducting negotiations between India and the EAEU. This document outlines the scope of negotiations, the structure of negotiating groups, timelines for negotiation rounds, and the decision-making processes that will govern the talks. While the specific contents of the Terms of Reference have not been publicly disclosed in their entirety, standard practice suggests that such documents include provisions for dispute resolution mechanisms during negotiations, confidentiality clauses, and the framework for technical consultations on specific sectors.

Following the signing ceremony, Ajay Bhadoo engaged in discussions with Andrei Slepnev, the Minister in charge of trade at the Eurasian Economic Commission, along with heads of various negotiation groups. These consultations focused on reviewing the implementation roadmap and identifying the next steps required to launch formal negotiations. The establishment of sector-specific negotiating groups suggests that the agreement will follow a modular approach, addressing different aspects of trade relations through specialized working groups that can progress simultaneously.

The involvement of multiple negotiating groups indicates the agreement’s intended scope will extend beyond simple tariff reductions. Modern free trade agreements typically encompass provisions related to services trade, investment protection, intellectual property rights, government procurement, competition policy, and regulatory cooperation. The complexity of these negotiations requires specialized expertise across various domains, justifying the creation of dedicated working groups for each major area.

Sectoral Implications and Market Access Opportunities

Pharmaceuticals and Healthcare Products

India’s pharmaceutical industry stands to gain substantially from enhanced market access to EAEU countries. Indian generic drug manufacturers have already established a presence in several EAEU markets, particularly Russia and Kazakhstan. A free trade agreement could reduce tariff barriers on pharmaceutical products while potentially addressing non-tariff barriers related to registration procedures, clinical trial requirements, and intellectual property protections that currently impede smoother market access.

The EAEU’s pharmaceutical market represents significant potential for Indian exporters, given the region’s healthcare needs and India’s capabilities as a leading producer of affordable generic medications. However, regulatory harmonization will be crucial to fully realize this potential. The negotiating process will need to address sanitary and phytosanitary measures, good manufacturing practices recognition, and the mutual acceptance of pharmaceutical standards to facilitate trade while ensuring patient safety.

Agricultural Products and Food Processing

Agriculture represents a sensitive sector in free trade negotiations, both for India and EAEU member states. India’s agricultural exports, including rice, tea, coffee, spices, and processed foods, could find expanded markets within the EAEU if tariff and non-tariff barriers are appropriately addressed. Conversely, India will need to carefully consider the impact of agricultural imports from EAEU countries on domestic farmers, particularly in sectors where domestic production requires continued protection for food security and livelihood preservation.

The negotiation of rules of origin for agricultural products will be particularly important to prevent circumvention and ensure that the benefits of the agreement accrue to producers in the participating countries. Additionally, addressing sanitary and phytosanitary measures through mutual recognition agreements or harmonization of standards can significantly reduce trade friction in agricultural products.

Information Technology and Services

India’s information technology and IT-enabled services sector represents one of the country’s strongest export capabilities. The EAEU market offers opportunities for Indian IT companies to expand their presence through enhanced services trade provisions in the FTA. Negotiations will likely address market access for services, movement of natural persons for service delivery, recognition of professional qualifications, and data localization requirements that affect IT service providers.

The services component of the free trade agreement could follow the General Agreement on Trade in Services framework, which allows countries to make specific commitments regarding market access and national treatment across different service sectors and modes of supply. For India, securing commitments on Mode 4 (movement of natural persons) will be particularly important given the industry’s reliance on the ability to send professionals to client locations for project delivery.

Textiles and Apparel

India’s textile and apparel industry, one of the largest employers in the manufacturing sector, views the EAEU as a potential growth market. The elimination of tariff barriers on textile products could enhance the competitiveness of Indian textiles in EAEU markets. However, the sector faces challenges related to meeting specific technical standards and regulations that vary across EAEU member states.

Negotiations on textiles will need to address rules of origin that account for the global nature of textile supply chains while ensuring sufficient local content to justify preferential treatment. The agreement might also include provisions for technical cooperation to help Indian exporters meet EAEU technical requirements and facilitate certification processes.

Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises: Expanding Commercial Opportunities

The Terms of Reference specifically acknowledge the anticipated benefits for micro, small and medium enterprises, recognizing that MSMEs form the backbone of India’s export sector and require special attention in trade agreements. MSMEs often face disproportionate challenges in accessing foreign markets due to limited resources for understanding foreign regulations, establishing distribution networks, and meeting compliance requirements.

The free trade agreement can address MSME concerns through several mechanisms. First, simplified rules of origin procedures can reduce the documentary burden on small exporters. Second, provisions for mutual recognition of conformity assessment can eliminate duplicate testing and certification requirements. Third, enhanced transparency in regulations and trade procedures helps MSMEs navigate foreign markets more effectively. Fourth, the establishment of trade facilitation mechanisms, including help desks and information portals, can provide targeted support to small businesses seeking to export.

The negotiation process should consider incorporating a dedicated chapter on MSME cooperation, as seen in recent Indian trade agreements. Such chapters typically include provisions for enhancing MSME participation in global value chains, facilitating access to trade finance, promoting digital trade platforms that benefit small businesses, and encouraging cooperation between MSME support institutions in partner countries.

Trade Facilitation and Customs Cooperation

Modern free trade agreements extend beyond tariff reductions to address trade facilitation measures that reduce the time and cost of moving goods across borders. The India-EAEU Free Trade Agreement negotiations will likely incorporate provisions aligned with the World Trade Organization’s Trade Facilitation Agreement, which India ratified in 2016. These provisions could include commitments on transparency and predictability in customs procedures, simplification of import and export documentation, implementation of risk management systems, and establishment of authorized economic operator programs.

Customs cooperation provisions can enhance the effective implementation of the agreement by addressing issues such as verification of rules of origin, exchange of customs data, mutual administrative assistance in preventing customs fraud, and harmonization of customs valuation methodologies. The development of electronic systems for submitting and processing trade documents can significantly reduce clearance times and facilitate commerce, particularly for time-sensitive products.

Investment Protection and Promotion

While the primary focus of free trade agreements is on trade in goods and services, investment provisions have become increasingly common in modern trade agreements. India and the EAEU both seek to attract foreign investment for economic development, making investment protection and promotion a natural component of their negotiations. The agreement could include provisions on investment liberalization, national treatment for established investments, fair and equitable treatment standards, and investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms.

India’s approach to investment protection has evolved following its experience with bilateral investment treaties that led to numerous arbitration cases. The Model Indian Bilateral Investment Treaty, finalized in 2016, reflects this evolution by incorporating safeguards such as narrower definitions of investment, exhaustion of local remedies before international arbitration, and carve-outs for sensitive sectors. The EAEU negotiations will likely reflect this more cautious approach while still providing sufficient protection to encourage investment flows.

Regulatory Cooperation and Standards Harmonization

Technical barriers to trade often pose greater obstacles than tariffs in contemporary international commerce. Differences in product standards, testing requirements, certification procedures, and labeling regulations can effectively prevent market access even when tariff barriers are eliminated. The India-EAEU FTA negotiations must address these technical barriers through provisions on regulatory cooperation and standards harmonization.

The agreement might establish mechanisms for mutual recognition of conformity assessment, whereby products tested and certified in one country are accepted in partner countries without additional testing. This reduces costs and delays for exporters while maintaining appropriate standards for consumer protection and safety. Additionally, regulatory cooperation chapters can promote alignment of standards with international norms, enhance transparency in standard-setting processes, and provide for dialogue between regulatory authorities.

Intellectual Property Rights Considerations

Intellectual property protection represents a sensitive area in trade negotiations, balancing innovation incentives with access to knowledge and technology. India has consistently advocated for a balanced approach to intellectual property rights that promotes innovation while ensuring access to essential goods like medicines. The EAEU countries have varying levels of intellectual property protection, and the negotiations will need to find common ground that satisfies both parties’ interests.

The intellectual property chapter of the agreement might address patents, trademarks, copyrights, geographical indications, and protection of traditional knowledge. Given India’s pharmaceutical industry interests, provisions related to patent linkages, data exclusivity, and compulsory licensing will require careful negotiation to preserve India’s ability to produce generic medicines while respecting the EAEU’s intellectual property framework.

Competition Policy and State-Owned Enterprises

Competition policy provisions in free trade agreements aim to ensure that the benefits of trade liberalization are not undermined by anticompetitive practices. As both India and EAEU countries have significant state-owned enterprise sectors, the agreement will need to address the competitive neutrality of state-owned entities and prevent anticompetitive conduct that could distort trade.

India’s Competition Act, 2002, provides the domestic legal framework for addressing anticompetitive practices, including cartels, abuse of dominant position, and anticompetitive mergers. The FTA negotiations might include provisions for cooperation between competition authorities, exchange of information on competition matters, and commitments to apply competition laws in a non-discriminatory manner. However, both parties will likely seek carve-outs for strategic sectors where state involvement is considered necessary for national security or economic development.

Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

Effective dispute resolution mechanisms are essential for ensuring that parties comply with their obligations under the agreement and for providing predictability to exporters and investors. The India-EAEU Free Trade Agreement will likely establish a multi-tiered dispute resolution system, beginning with consultations between the parties, potentially followed by mediation or good offices, and ultimately providing for arbitration through an ad hoc panel or standing tribunal.

The design of dispute resolution mechanisms requires balancing effectiveness with sovereignty concerns. India has traditionally preferred diplomatic approaches to trade disputes and has been cautious about binding arbitration mechanisms that significantly constrain policy flexibility. The negotiations will need to find an appropriate balance that provides sufficient enforcement while allowing parties reasonable flexibility to respond to legitimate public policy concerns.

Environmental and Labor Standards

Contemporary trade agreements increasingly incorporate provisions related to environmental protection and labor standards, reflecting growing recognition that trade liberalization should not come at the expense of environmental sustainability or workers’ rights. The India-EAEU negotiations might include chapters addressing environmental cooperation, sustainable development, and labor rights, though the specific commitments will depend on the negotiating priorities of both parties.

India has traditionally viewed environmental and labor provisions in trade agreements with some caution, concerned that such provisions might be used as protectionist tools or might impose standards that do not account for different levels of development. However, India has increasingly accepted that appropriate environmental and labor provisions can be part of a balanced trade agreement, provided they focus on cooperation and capacity building rather than punitive enforcement mechanisms.

Implementation Timeline and Institutional Arrangements

Following the signing of the Terms of Reference in September 2025, the negotiating parties have expressed their commitment to concluding the agreement as expeditiously as possible. Based on India’s experience with other recent trade negotiations, the negotiation process typically extends over eighteen to thirty-six months, depending on the complexity of issues and the political will of both parties. Statements from Indian diplomatic officials suggest an ambitious timeline of approximately eighteen months for completing the negotiations.[6]

The institutional arrangements for implementing the agreement will likely include the establishment of a joint committee or council comprising senior officials from both sides, responsible for overseeing implementation, addressing implementation issues, and considering amendments or updates to the agreement. Sector-specific committees might be created to address technical issues in particular areas such as customs procedures, sanitary measures, or technical barriers to trade.

Challenges and Critical Considerations

Despite the promising potential of the India-EAEU Free Trade Agreement, several challenges must be navigated during negotiations and implementation. One significant concern involves balancing trade liberalization with protection of sensitive domestic sectors. Indian agriculture, for instance, employs a substantial portion of the population, and hasty liberalization could adversely affect farmer livelihoods. Similarly, certain manufacturing sectors that are still developing require continued protection from import surges until they achieve sufficient competitiveness.

The diversity within the EAEU itself presents coordination challenges. While Russia dominates the union economically, the other member states have distinct economic profiles and priorities. Ensuring that the agreement addresses the specific interests of all EAEU members while maintaining coherence requires careful negotiation and potentially differentiated timelines for implementing various provisions.

Geopolitical considerations cannot be ignored in India’s engagement with the EAEU. The union’s close relationship with Russia and China, combined with India’s own strategic relationships with Western powers, creates a complex diplomatic landscape. The trade agreement must be structured to yield economic benefits without creating political complications or constraining India’s flexibility in its broader foreign policy.

Non-tariff barriers often prove more challenging than tariff reductions in trade agreements. Differences in regulatory frameworks, standards, and certification requirements between India and EAEU countries can impede trade even after tariff elimination. The agreement’s success will depend significantly on its effectiveness in addressing these non-tariff barriers through regulatory cooperation and harmonization initiatives.

Comparative Analysis with India’s Other Trade Agreements

India’s trade agreement landscape provides useful reference points for understanding the likely contours of the India-EAEU Free Trade Agreement. The India-Korea Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, which entered into force in 2010, demonstrates India’s willingness to enter into ambitious agreements covering not just goods but also services, investment, and economic cooperation. However, concerns about the agreement’s impact on India’s trade balance led to subsequent reviews and adjustments, highlighting the importance of balanced market access commitments.

More recently, the India-European Free Trade Association Trade and Economic Partnership Agreement, signed in March 2024, showcases India’s evolving approach to trade agreements. This agreement includes innovative provisions on investment promotion, with EFTA states committing to facilitate significant investment flows into India. The India-EAEU negotiations might similarly incorporate investment promotion commitments given both parties’ interest in attracting foreign investment for economic development.[7]

The India-United Kingdom Free Trade Agreement, concluded in July 2025, represents another relevant comparison. This agreement reportedly includes provisions on digital trade, intellectual property rights, and services liberalization that reflect contemporary priorities in trade policy. The India-EAEU Free Trade Agreement will need to address similar issues, adapted to the specific contexts and priorities of India and the EAEU member states.[8]

Economic Impact Projections

While comprehensive economic modeling of the proposed India-EAEU Free Trade Agreement has not been publicly released, certain projections can be made based on the existing trade relationship and the potential for trade creation. The current bilateral trade of USD 69 billion provides a baseline, with significant potential for expansion across multiple sectors. Trade agreements typically generate trade creation effects through tariff elimination, trade diversion effects as preferential access shifts trade patterns, and dynamic effects from increased competition and economies of scale.

For Indian exporters, particularly in pharmaceuticals, IT services, textiles, and certain agricultural products, the agreement could open substantial new market opportunities. The EAEU’s combined market of over 180 million consumers represents significant demand potential. On the import side, India could benefit from access to EAEU energy resources, minerals, and certain manufactured goods at competitive prices, potentially reducing input costs for Indian industries.

The agreement’s impact on micro, small and medium enterprises deserves particular attention in economic assessments. If the agreement successfully incorporates MSME-friendly provisions on trade facilitation, technical assistance, and simplified procedures, the trade creation effects for small businesses could be substantial. However, MSMEs are also potentially vulnerable to import competition, necessitating appropriate adjustment assistance and capacity building programs.

The Road Ahead

As India and the EAEU embark on formal negotiations for a free trade agreement, both parties enter with clear economic interests and strategic objectives. For India, diversifying trade partnerships and securing access to new markets aligns with its goal of becoming a USD five trillion economy. The EAEU represents an underexplored market where Indian exporters can potentially gain first-mover advantages in sectors where they possess competitive strengths.

For the EAEU, deepening economic engagement with India offers a hedge against excessive dependence on any single economic partner and provides access to India’s growing consumer market and manufacturing capabilities. The agreement can also strengthen the EAEU’s institutional capacity and international profile as it seeks to expand its network of free trade agreements.

The success of the India-EAEU Free Trade Agreement will ultimately depend on the negotiators’ ability to craft an agreement that is comprehensive enough to yield significant economic benefits while being sensitive to the legitimate concerns of stakeholders in both parties. This requires not just technical expertise in trade policy but also political wisdom in balancing competing interests and managing implementation challenges. The Terms of Reference signed in September 2025 have established the framework for this endeavor, and the coming months of negotiations will determine whether this framework can be translated into a mutually beneficial trade agreement that stands the test of time.

Conclusion

The initiation of free trade agreement negotiations between India and the Eurasian Economic Union represents a significant development in international trade relations. Built upon a solid foundation of existing bilateral trade worth USD 69 billion and supported by a clear legal framework under India’s Foreign Trade (Development and Regulation) Act, 1992, this agreement has the potential to reshape trade flows between South Asia and Eurasia. The Terms of Reference signed in Moscow in September 2025 establish the procedural and organizational basis for negotiations that will likely span the next eighteen to twenty-four months.