Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

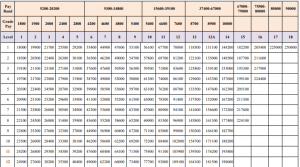

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

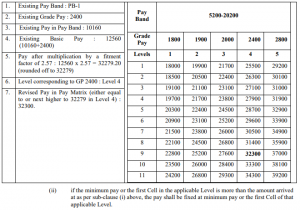

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

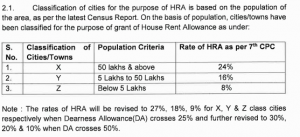

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

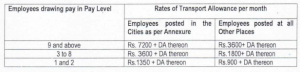

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Consent and Social Impact Assessment Under LARR Act: Step-by-Step Guide

Introduction

The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 (LARR Act) fundamentally transformed India’s land acquisition framework by introducing mandatory consent requirements and Social Impact Assessment procedures [1]. Enacted on 26th September 2013 and effective from 1st January 2014, this landmark legislation replaced the archaic Land Acquisition Act of 1894, establishing a more equitable and transparent mechanism for land acquisition while safeguarding the rights of affected families [2].

The LARR Act represents a paradigmatic shift from the colonial-era approach that prioritized state interests over individual rights. This legislation mandates participatory, informed, and transparent processes for land acquisition, particularly through its consent provisions and Social Impact Assessment requirements. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for legal practitioners, government officials, project developers, and affected communities navigating the complex terrain of land acquisition in contemporary India.

Legal Framework and Statutory Provisions

Constitutional Foundation

Land acquisition operates within India’s constitutional framework where land is a state subject under Entry 18 of List II (State List) of the Seventh Schedule. However, the LARR Act derives its authority from Entry 42 of List III (Concurrent List), which pertains to acquisition and requisitioning of property. The constitutional validity of the Act stems from the doctrine of eminent domain, balanced against the fundamental right to property under Article 300A of the Constitution [3].

Defining Public Purpose Under Section 2

Section 2(1) of the LARR Act provides an exhaustive definition of “public purpose,” which includes strategic purposes related to national security and defence, infrastructure projects including roads, highways, ports, railways, airports, and projects for planned development or improvement of village sites. The definition specifically excludes private hospitals, private educational institutions, and projects primarily serving commercial purposes unless they fall within the prescribed categories [4].

The Act distinguishes between different categories of land acquisition based on the acquiring entity:

- Government acquisition for public purposes under Section 2(1)

- Acquisition for private companies requiring 80% consent

- Acquisition for public-private partnerships requiring 70% consent

Consent Requirements Under Section 2(2)

Section 2(2) of the LARR Act establishes the fundamental principle of prior informed consent, stating that for private companies, “the prior consent of at least eighty per cent of those affected families” must be obtained, while for public-private partnership projects, “the prior consent of at least seventy per cent of those affected families” is required [5]. This provision represents a revolutionary departure from the 1894 Act, which allowed forcible acquisition without landowner consent.

The consent requirement applies specifically to “affected families” as defined under Section 3(c), which includes landowners whose land is acquired and families whose primary source of livelihood is dependent on the land acquired. The process of obtaining consent must be carried out simultaneously with the Social Impact Assessment study under Section 4.

Social Impact Assessment: Statutory Framework

Section 4 Requirements

Section 4 of the LARR Act mandates that whenever land acquisition is proposed, except in cases of urgency under Section 40, a Social Impact Assessment study must be conducted by an expert group [6]. This assessment serves multiple purposes: identifying project-affected families, assessing social impact, evaluating whether public purpose justifies land acquisition, and examining alternative options to minimize displacement.

The SIA study must be completed within six months of its commencement and requires consultation with Panchayati Raj Institutions and local communities. The expert group conducting the SIA must include social science, rehabilitation, and resettlement specialists, along with representatives from Panchayati Raj Institutions and affected communities.

Public Hearing Requirements

The Act mandates public hearings in affected areas after providing adequate publicity regarding date, time, and venue. These hearings must ascertain opinions of affected families, which are recorded and included in the SIA report. The public hearing process ensures transparency and provides affected communities with meaningful participation in the land acquisition process.

Step-by-Step Procedural Guide

Phase I: Preliminary Assessment and Planning

Step 1: Project Identification and Feasibility Study The acquiring body must first establish the public purpose for land acquisition and conduct preliminary feasibility studies. This involves identifying the specific land parcels required, estimating the number of affected families, and determining whether the project falls under categories requiring consent.

Step 2: Determining Applicability of Consent Requirements Based on the nature of the acquiring entity and project type, authorities must determine whether 70% or 80% consent is required, or whether the project is exempt from consent requirements due to its public purpose nature under Section 2(1).

Step 3: Initial Community Engagement Before formal proceedings begin, acquiring authorities should engage with local communities, Gram Sabhas, and Panchayati Raj Institutions to explain the project’s objectives and gather preliminary feedback.

Phase II: Social Impact Assessment Process

Step 4: Constituting the Expert Group An expert group must be constituted comprising specialists in social sciences, rehabilitation and resettlement, economics, agriculture, and environmental sciences. The group must include at least one representative each from Panchayati Raj Institutions, affected areas, and voluntary organizations working in the area.

Step 5: Conducting Field Studies The expert group conducts detailed field studies covering socio-economic surveys of affected families, assessment of impact on livelihood patterns, evaluation of infrastructure and facilities that may be affected, and analysis of environmental consequences.

Step 6: Stakeholder Consultations Extensive consultations with affected families, local communities, civil society organizations, and government agencies must be conducted. These consultations should employ multiple methods including focus group discussions, individual interviews, and community meetings.

Step 7: Public Hearing Organization Public hearings must be organized with adequate advance notice through local newspapers and official gazettes. The hearings should be conducted in local languages and provide opportunities for all affected parties to express their views and concerns.

Phase III: Consent Acquisition Process

Step 8: Identification of Affected Families Based on SIA findings, authorities must prepare a comprehensive list of affected families as defined under Section 3(c). This includes not only landowners but also families dependent on the land for their livelihood, including agricultural laborers, tenants, and other stakeholders.

Step 9: Information Dissemination Affected families must receive complete information about the project including its benefits, rehabilitation and resettlement package, compensation details, and timeline for implementation. Information should be provided in accessible formats and local languages.

Step 10: Consent Collection Process The consent collection must follow prescribed procedures ensuring that each affected family understands the implications of their decision. Consent must be free, prior, and informed, obtained without coercion or inducement. The process should be transparent and verifiable.

Step 11: Verification and Documentation The consent process must be properly documented with clear records of how consent was obtained, the percentage of families providing consent, and any objections or concerns raised by families refusing consent.

Phase IV: Assessment and Approval

Step 12: SIA Report Preparation The expert group prepares a detailed SIA report including assessment findings, public hearing outcomes, consent statistics, impact mitigation measures, and recommendations regarding project approval or modification.

Step 13: Government Review and Evaluation The appropriate government reviews the SIA report, consent documentation, and project feasibility. This evaluation considers whether the required consent threshold has been met and whether the project’s benefits justify its social costs.

Step 14: Decision Making and Notification Based on the SIA report and consent process outcomes, the government decides whether to proceed with land acquisition. If approved, a preliminary notification under Section 11 is issued, beginning the formal acquisition process.

Regulatory Oversight and Compliance

Administrative Framework

The LARR Act establishes multiple levels of administrative oversight to ensure compliance with consent and SIA requirements. District Collectors serve as the primary implementing authority, while state governments maintain overall responsibility for Act implementation. The National Monitoring Committee for Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement monitors implementation across states.

Grievance Redressal Mechanisms

The Act provides for grievance redressal through multiple channels including the Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Authority established under Section 51, civil courts for compensation disputes, and administrative appeals to higher authorities [7]. These mechanisms ensure that affected parties have recourse in case of procedural violations or inadequate compensation.

Legal Precedents and Judicial Interpretation

Supreme Court Pronouncements

The Supreme Court has interpreted the LARR Act’s consent and SIA provisions in several landmark cases. In the matter concerning Tamil Nadu’s attempt to revive pre-2013 acquisition laws, the Supreme Court upheld the state’s right to deviate from the LARR Act under Article 254(2) of the Constitution, provided it receives Presidential assent [8]. This decision significantly impacts the uniform application of consent and SIA requirements across states.

High Court Decisions

Various High Courts have adjudicated disputes concerning consent validity, SIA adequacy, and procedural compliance. The Madras High Court initially struck down Tamil Nadu’s attempts to bypass LARR requirements, emphasizing the mandatory nature of consent and SIA provisions before being overruled by subsequent state legislation.

Challenges and Implementation Issues

Practical Difficulties in Consent Acquisition

Obtaining 70-80% consent from affected families presents significant practical challenges. These include difficulties in identifying all affected families, ensuring informed decision-making in communities with varying literacy levels, and managing dissent within families and communities. The threshold requirements, while protective of landowner rights, can effectively provide veto power to minority groups, potentially stalling legitimate development projects.

SIA Quality and Standardization

The quality and standardization of SIA studies remain persistent challenges. Variations in expert group composition, assessment methodologies, and reporting standards across states create inconsistencies in SIA outcomes. The lack of standardized guidelines for SIA preparation has led to studies of varying quality and depth.

Timeline and Cost Implications

The consent and SIA requirements significantly extend project timelines and increase costs. The mandatory procedures, while ensuring transparency and participation, can extend the acquisition process by 50 months under optimal conditions, affecting project viability and economic returns [9].

Amendments and Recent Developments

2015 Amendment Attempts

The government’s attempts to amend the LARR Act in 2015 sought to exempt five categories of projects – defence, rural infrastructure, affordable housing, industrial corridors, and infrastructure projects where government retains land ownership – from consent and SIA requirements. These amendments faced strong opposition and ultimately lapsed, maintaining the original Act’s stringent requirements.

State-Level Modifications

Several states have enacted legislation modifying LARR applicability within their jurisdictions. Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and Karnataka have passed laws exempting certain categories of projects from LARR requirements, effectively reverting to pre-2013 acquisition procedures for specific project types. These modifications raise questions about the uniform application of consent and SIA standards across India.

Best Practices and Recommendations

Ensuring Meaningful Consent

Meaningful consent requires more than mere numerical compliance with threshold requirements. Best practices include providing comprehensive information in accessible formats, allowing adequate time for decision-making, ensuring absence of coercion, and maintaining transparency throughout the process. Consent should be viewed as an ongoing process rather than a one-time event.

Enhancing SIA Quality

Improving SIA quality requires standardized methodologies, qualified expert groups, adequate time allocation, and robust quality assurance mechanisms. SIA studies should adopt participatory approaches, employ mixed-method research strategies, and provide clear recommendations for impact mitigation and enhancement measures.

Stakeholder Engagement Strategies

Effective stakeholder engagement involves early and continuous consultation, multi-channel communication strategies, culturally appropriate engagement methods, and feedback incorporation mechanisms. Engaging with community leaders, civil society organizations, and local institutions can facilitate smoother consent processes and more accurate SIA outcomes.

Future Outlook and Emerging Trends

Digital Technologies in Consent and SIA

Emerging digital technologies offer opportunities to enhance consent and SIA processes through online platforms for information dissemination, digital consent collection systems, Geographic Information Systems for impact mapping, and data analytics for social impact prediction. However, digital divide issues must be addressed to ensure equitable access and participation.

Climate Change Considerations

Climate change impacts increasingly influence land acquisition decisions and SIA assessments. Future frameworks must incorporate climate resilience considerations, environmental sustainability assessment, and adaptation measures into consent and SIA processes.

Balancing Development and Rights

The ongoing challenge of balancing development imperatives with individual and community rights requires nuanced approaches that recognize legitimate development needs while maintaining protective safeguards for affected communities. This balance will likely evolve through judicial interpretation, legislative amendments, and administrative innovations.

Conclusion

The LARR Act’s consent and Social Impact Assessment provisions represent significant advances in protecting landowner rights and ensuring participatory development. While implementation challenges persist, these mechanisms provide essential safeguards against arbitrary land acquisition and promote more equitable development outcomes. Success in implementing these provisions requires continued commitment to transparency, meaningful participation, and adaptive management approaches that respond to emerging challenges while maintaining core protective principles.

The evolution of these provisions through judicial interpretation, administrative practice, and potential legislative amendments will continue shaping India’s land acquisition landscape. Legal practitioners, government officials, and civil society organizations must remain engaged in this evolutionary process to ensure that the LARR Act’s transformative potential is fully realized while addressing legitimate development needs and protecting vulnerable communities.

References

[1] Department of Land Resources, Government of India. “The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013.” Available at: https://dolr.gov.in/act-rules/

[2] PRS Legislative Research. “The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Bill, 2013.” Available at: https://prsindia.org/billtrack/the-right-to-fair-compensation-and-transparency-in-land-acquisition-rehabilitation-and-resettlement-bill-2013

[3] Indian Kanoon. “Section 2(2) in The Right To Fair Compensation And Transparency In Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013.” Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/157315570/

[4] Bajaj Finserv. “Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in LARR Act 2013.” Available at: https://www.bajajfinserv.in/land-acquisition-act-2013

[5] Rest The Case. “Right to Fair Compensation in Land Acquisition.” Available at: https://restthecase.com/knowledge-bank/right-to-fair-compensation-in-land-acquisition

[6] iPleaders. “The Land Acquisition Act, 2013.” Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/the-land-acquisition-act-2013/

[7] PRS Legislative Research. “The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (Amendment) Bill, 2015.” Available at: https://prsindia.org/billtrack/the-right-to-fair-compensation-and-transparency-in-land-acquisition-rehabilitation-and-resettlement-amendment-bill-2015

[8] The Wire. “In Crucial Verdict, Supreme Court Allows TN to Acquire Land Using State Laws, Not LARR.” Available at: https://m.thewire.in/article/law/supreme-court-tamil-nadu-land-acquisition/amp

[9] O.P. Jindal Global University. “The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation, and Resettlement Act, 2013.” Available at: https://jgu.edu.in/jsgp/jindal-policy-research-lab/the-right-to-fair-compensation-and-transparency-in-land-acquisition-rehabilitation-and-resettlement-act-2013/

Land Acquisition Act, 1894 and LARR Act, 2013: A Comparative Analysis

Introduction

Land acquisition has remained one of the most contentious legal and socio-economic issues in India since independence. The process of acquiring private land for public purposes has evolved significantly from the colonial-era Land Acquisition Act, 1894 to the modern Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 (LARR Act). [1] This transformation reflects India’s journey from a colonial administrative framework to a democratic constitutional republic that seeks to balance developmental needs with individual property rights and social justice.

The Land Acquisition Act, 1894, enacted during British rule, served as the primary legislation governing land acquisition in India for over a century. However, its colonial origins and inadequate protection for landowners’ rights made it increasingly incompatible with democratic principles and constitutional values. [2] The LARR Act, 2013, which came into force on January 1, 2014, represents a paradigmatic shift towards a more humane, participatory, and transparent approach to land acquisition that prioritizes fair compensation, rehabilitation, and resettlement of affected persons.

This comparative analysis examines the fundamental differences, improvements, and challenges associated with both legislative frameworks, while evaluating their impact on property rights, developmental goals, and social justice in contemporary India.

Historical Context and Legislative Evolution

Colonial Legacy of the Land Acquisition Act, 1894

The Land Acquisition Act, 1894, was a product of imperial administration designed to facilitate state control over land for infrastructural and administrative purposes during British rule. The Act was premised on the doctrine of eminent domain, which grants the sovereign the power to acquire private property for public use, subject to payment of compensation. [3] The colonial framework prioritized state interests over individual rights, reflecting the broader administrative philosophy of the British Raj that emphasized efficient governance over participatory democracy.

Under the 1894 Act, the government possessed extensive powers to acquire land for “public purposes,” a term that was broadly defined and often subject to administrative discretion. The Act provided minimal consultation mechanisms and limited opportunities for affected parties to challenge acquisition decisions. Compensation was typically calculated based on market value at the time of notification, without considering inflation, future potential, or the broader socio-economic impact on displaced families.

Constitutional Foundation and Property Rights

The evolution of land acquisition law in India cannot be understood without examining the constitutional transformation of property rights. Originally, the Indian Constitution enshrined the right to property as a fundamental right under Articles 19(1)(f) and 31. [4] However, tensions between individual property rights and state-led development policies, particularly in the context of land reforms and nationalization programs, led to significant constitutional amendments.

The Forty-Fourth Amendment Act, 1978, removed the right to property from the list of fundamental rights and inserted Article 300A, which provides that “no person shall be deprived of his property save by authority of law.” [5] This constitutional change shifted property rights from fundamental constitutional protection to ordinary constitutional rights, thereby reducing the level of judicial scrutiny applicable to state acquisition of private property.

Genesis of the LARR Act, 2013

The need for comprehensive reform of land acquisition law became increasingly apparent in the post-liberalization era as India embarked on ambitious infrastructure development projects. The inadequacies of the 1894 Act became particularly evident in cases of large-scale displacement for industrial projects, special economic zones, and urban development initiatives. Public protests, judicial interventions, and policy debates highlighted the urgent need for legislation that would balance developmental imperatives with social justice and human rights concerns.

The National Advisory Council, under the chairmanship of Sonia Gandhi, played a crucial role in formulating the policy framework for the new land acquisition law. After extensive consultations with civil society organizations, legal experts, and affected communities, the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Bill was introduced in Parliament in 2011 and subsequently enacted as the LARR Act, 2013.

Key Provisions Compared: Land Acquisition Act, 1894 vs LARR Act, 2013

Definition and Scope of Public Purpose

The 1894 Act provided a broad and somewhat ambiguous definition of “public purpose,” which included any purpose useful to the public. This expansive interpretation often led to misuse of acquisition powers for projects that primarily benefited private entities rather than serving genuine public interests. The Act’s Section 3(f) definition was criticized for its vagueness and potential for abuse by acquiring authorities.

In contrast, the LARR Act, 2013, provides a more detailed and circumscribed definition of public purpose under Section 2(1)(zk). The Act specifically enumerates activities that constitute public purpose, including strategic purposes related to naval, military, air force, and armed forces, infrastructure projects, planned development or improvement of village sites, and projects for residential purposes for the poor and landless. [1] This more precise definition aims to prevent misuse of acquisition powers while ensuring that genuine public welfare projects can proceed efficiently.

Importantly, the Land Acquisition Act, 1894 and LARR Act, 2013 differ significantly in their approach to acquisition for private companies. The LARR Act excludes such acquisitions except in specific circumstances involving public-private partnerships where the government retains ownership of the acquired land. This marks a clear departure from the 1894 Act, which had allowed relatively unrestricted acquisition for company purposes.

Consent Requirements and Community Participation

One of the most significant innovations of the LARR Act, 2013, is the introduction of mandatory consent requirements for certain categories of land acquisition. Under Section 2(2), when land is acquired for private companies, the consent of at least 80% of the affected families must be obtained through a prior informed consultation process. For public-private partnership projects, the consent threshold is set at 70% of affected families. [1]

This consent mechanism represents a fundamental shift from the top-down approach of the 1894 Act, which required no consultation with affected communities. The new framework recognizes the principle of free, prior, and informed consent that is increasingly recognized in international human rights law as essential for protecting the rights of affected populations.

The LARR Act also mandates meaningful consultation with local self-government institutions and Gram Sabhas, ensuring that acquisition decisions are made with input from democratically elected local representatives. This participatory approach aims to enhance the legitimacy and social acceptance of acquisition projects while reducing conflicts between acquiring authorities and affected communities.

Social Impact Assessment and Environmental Considerations

The LARR Act, 2013, introduces the revolutionary concept of Social Impact Assessment (SIA) as a mandatory prerequisite for land acquisition. Section 4 of the Act requires that every acquisition proposal be subjected to a comprehensive SIA study that evaluates the potential impact on affected families and the local community. [1] The SIA must assess whether the potential benefits of the proposed project outweigh the social costs and whether the project serves public purpose.

This requirement represents a dramatic departure from the 1894 Act, which contained no provisions for impact assessment or community consultation before acquisition decisions. The SIA framework draws inspiration from environmental impact assessment practices and international best practices in resettlement and rehabilitation.

The SIA study must examine various factors including the number of families likely to be affected, the impact on public and community properties, assessment of whether public purpose is served by the acquisition, and an evaluation of whether there are less disruptive alternatives available. This comprehensive assessment aims to ensure that acquisition decisions are made only after careful consideration of all relevant factors and stakeholder interests.

Compensation Framework and Calculation Methodology

The compensation provisions represent perhaps the most significant improvement from the 1894 Act to the LARR Act. Under the colonial-era legislation, compensation was typically limited to market value as determined by the Collector, often based on outdated records and circle rates that did not reflect actual market conditions. The 1894 Act provided for solatium of 15% above market value and interest on delayed payments, but these provisions were often inadequate to enable affected families to restore their livelihoods.

The LARR Act, 2013, introduces a much more generous and comprehensive compensation framework. Section 26 provides that compensation for rural land shall be at least four times the market value, while for urban areas, it shall be at least twice the market value. [1] Additionally, the Act provides for solatium equal to 100% of the compensation amount, effectively doubling the total payment to landowners.

The market value determination under the LARR Act is based on the higher of the average sale price for similar type of land situated in the village or vicinity during the preceding three years, or the average of the highest prices paid for similar land during the three years, or the circle rate. This methodology aims to ensure that compensation reflects actual market conditions rather than artificially suppressed government valuations.

Beyond monetary compensation, the LARR Act recognizes the need for comprehensive rehabilitation and resettlement measures. The Act requires that acquisition projects include detailed R&R plans that address the needs of not only landowners but also landless laborers, tenants, sharecroppers, and others whose livelihoods depend on the acquired land.

Rehabilitation and Resettlement Provisions

The 1894 Act contained no provisions for rehabilitation and resettlement, reflecting its narrow focus on compensating property owners without considering the broader social and economic disruption caused by displacement. This gap often resulted in impoverishment and marginalization of affected communities, particularly vulnerable groups such as indigenous peoples, agricultural laborers, and other economically disadvantaged populations.

The LARR Act, 2013, addresses this deficiency through comprehensive rehabilitation and resettlement provisions contained in Sections 31-41. The Act recognizes that displacement affects not only landowners but also various categories of affected persons including those whose primary source of livelihood is adversely affected. [1] The R&R framework includes provisions for alternative land, employment opportunities, training and skill development, healthcare facilities, educational facilities, and other essential services.

The Act establishes clear entitlements for different categories of affected persons, ensuring that vulnerable groups receive adequate support to restore and improve their livelihoods. These provisions reflect international best practices in development-induced displacement and resettlement, drawing from frameworks developed by institutions such as the World Bank and other multilateral development agencies.

Procedural Safeguards and Transparency Measures

The LARR Act, 2013, introduces numerous procedural innovations designed to enhance transparency and accountability in the acquisition process. The Act requires publication of acquisition notifications in local languages, mandatory public hearings, and opportunities for affected persons to raise objections and concerns. These procedural safeguards aim to ensure that acquisition decisions are made through fair and transparent processes that respect the rights and dignity of affected communities.

The Act also establishes time limits for various stages of the acquisition process, requiring that awards be made within 12 months of the acquisition notification and that possession be taken within 12 months of the award. If these timelines are not met, the acquisition lapses automatically, providing important protections against indefinite pending acquisition cases that plagued the implementation of the 1894 Act.

Judicial Interpretation and Case Law Development

Supreme Court Jurisprudence on Property Rights

The constitutional status of property rights has been shaped significantly by Supreme Court jurisprudence, particularly following the Forty-Fourth Amendment. In Jilubhai Nanbhai Khachar v. State of Gujarat (1994), the Supreme Court clarified that the right to property under Article 300A is not a fundamental right but remains a constitutional right that deserves protection. [4] This decision established that while property rights are not part of the basic structure of the Constitution, they cannot be arbitrarily violated by state action.

The Supreme Court has consistently held that any deprivation of property must be in accordance with procedures established by law and must serve legitimate public purposes. In State of Haryana v. Mukesh Kumar (2011), the Court emphasized that acquisition of property must follow due process and cannot be arbitrary or capricious.

Landmark Decision in Indore Development Authority v. Manoharlal (2020)

The most significant recent judicial interpretation of land acquisition law came in the Constitution Bench decision of Indore Development Authority v. Manoharlal and Others (2020). [6] This case resolved contradictory interpretations of Section 24(2) of the LARR Act, which deals with the lapsing of acquisition proceedings initiated under the 1894 Act.

The Supreme Court held that land acquisition proceedings do not lapse merely due to non-payment of compensation if the acquiring authority has taken physical possession of the land. The Court clarified that “payment” for purposes of Section 24(2) includes tendering of compensation, even if the landowner refuses to accept it, and deposit in government treasury satisfies the payment requirement. [6]

This decision has significant practical implications for thousands of pending acquisition cases and demonstrates the ongoing challenges in implementing the transition from the 1894 Act to the LARR Act. The judgment reflects the Court’s attempt to balance the interests of affected landowners with the practical realities of infrastructure development and project implementation.

Procedural Rights under Article 300A

In a recent landmark decision in Kolkata Municipal Corporation v. Bimal Kumar Shah (2024), the Supreme Court outlined seven essential procedural sub-rights that must be observed in any land acquisition process under Article 300A of the Constitution. [7] These include the right to notice, right to be heard, right to a reasoned decision, duty to acquire only for public purposes, right to fair compensation, right to efficient process, and right to conclusion of proceedings.

This decision represents a significant judicial elaboration of the procedural safeguards required for constitutional compliance in land acquisition cases. The Court emphasized that mere provision for compensation is insufficient and that comprehensive procedural protections are essential for protecting constitutional rights.

Implementation Challenges and Practical Implications

Administrative and Bureaucratic Challenges

The implementation of the LARR Act, 2013, has faced numerous administrative challenges that have affected its practical effectiveness. The requirement for Social Impact Assessment has created new bureaucratic processes that require specialized expertise and coordination between multiple agencies. Many state governments have struggled to develop adequate capacity for conducting meaningful SIA studies, leading to delays and procedural non-compliance.

The consent requirements, while democratically sound, have proved challenging to implement in practice. Determining who constitutes an “affected family” for purposes of consent calculation has been controversial, particularly in cases involving large joint families or disputed land ownership. The process of obtaining informed consent has also been complicated by information asymmetries and power imbalances between acquiring authorities and rural communities.

Economic and Development Implications

The enhanced compensation and rehabilitation requirements of the LARR Act have significantly increased the cost of land acquisition for development projects. While this reflects a more equitable distribution of development benefits, it has also created challenges for project viability and fiscal sustainability. Infrastructure projects, in particular, have experienced cost escalations and delays due to the more complex acquisition procedures.

The requirement for consent has effectively provided affected communities with veto power over development projects, which has been both celebrated as democratic empowerment and criticized as creating potential for obstruction of legitimate public projects. Balancing community rights with development imperatives remains an ongoing challenge in the implementation of the Act.

Regulatory Responses and Amendments

Recognizing some of the implementation challenges, the government has attempted various regulatory reforms to streamline the LARR Act while preserving its essential protections. The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (Amendment) Ordinance, 2014, sought to exempt certain categories of projects from key provisions of the Act, including defense projects, rural infrastructure, affordable housing, industrial corridors, and infrastructure projects where the government owns the land.

However, these amendment attempts faced significant political opposition and civil society resistance, reflecting the contested nature of land acquisition policy in India. The failure to enact permanent amendments demonstrates the entrenched nature of disagreements about the appropriate balance between development and community rights.

State-Level Variations and Federal Dynamics

Since land acquisition falls within the concurrent list of the Constitution, state governments have significant autonomy in implementing and modifying the central legislation. Several states have enacted their own land acquisition laws or amended the central Act to suit local conditions and development priorities. Tamil Nadu, for example, passed the Tamil Nadu Land Acquisition Laws (Revival of Operation, Amendment, and Validation) Act, 2019, which exempts certain categories of projects from LARR Act provisions. [8]

These state-level variations reflect the federal structure of Indian governance but also create potential for regulatory arbitrage and inconsistent protection of landowner rights across different states. The Supreme Court has generally upheld state governments’ authority to enact variations under Article 254(2) of the Constitution, subject to presidential assent.

Contemporary Challenges and Future Prospects

Urbanization and Metropolitan Development

Rapid urbanization in India has created new challenges for land acquisition policy that were not fully anticipated in either the Land Acquisition Act 1894 or the LARR Act, 2013. Metropolitan expansion, smart city development, and urban infrastructure projects require large-scale land assembly that often involves complex patterns of ownership and use. The LARR Act’s rural-centric approach may be inadequate for addressing the sophisticated land markets and diverse stakeholder interests characteristic of urban areas.

Urban land acquisition also raises different social and economic issues compared to rural acquisition. Urban landowners are often more financially sophisticated and politically connected than rural farmers, creating different dynamics in negotiation and compensation processes. The standard compensation formulas may be inadequate for high-value urban land where market prices are highly volatile and speculative.

Environmental and Climate Considerations

Contemporary land acquisition must grapple with environmental degradation and climate change considerations that were largely absent from both historical legislative frameworks. Large-scale land acquisition for industrial projects, mining, and infrastructure development has significant environmental impacts that may undermine long-term sustainability and community welfare.

The LARR Act’s Social Impact Assessment framework provides some tools for environmental consideration, but critics argue that these provisions are insufficient for addressing complex ecological and climate impacts. Future policy development may need to integrate more sophisticated environmental impact assessment and mitigation requirements into the land acquisition framework.

Digital Technology and Land Records

The digitization of land records and property registration systems creates new opportunities for improving transparency and efficiency in land acquisition processes. Electronic land records can provide more accurate information about ownership, reduce disputes, and facilitate faster processing of acquisition cases. However, digital systems also raise concerns about data privacy, security, and potential for technological exclusion of marginalized communities.

The integration of digital technologies into land acquisition processes will require careful attention to ensuring that technological innovations enhance rather than undermine the participatory and transparent principles established by the LARR Act.

Conclusion

The transition from the Land Acquisition Act, 1894, to the LARR Act, 2013, represents a fundamental transformation in India’s approach to balancing development imperatives with individual rights and social justice. The colonial-era framework’s emphasis on state power and administrative efficiency has been replaced by a more democratic, participatory, and rights-based approach that recognizes the complex social and economic impacts of development-induced displacement.

The LARR Act’s innovations in consent requirements, social impact assessment, enhanced compensation, and comprehensive rehabilitation represent significant improvements over the 1894 Act’s limited protections. These changes reflect India’s evolution as a constitutional democracy committed to protecting vulnerable populations while pursuing development goals.

However, the implementation experience of the LARR Act also demonstrates the ongoing challenges in balancing competing interests and values in land acquisition policy. The tension between democratic participation and administrative efficiency, between enhanced protection for affected communities and project viability, and between local autonomy and national development priorities continues to shape policy debates and judicial interpretation.

The future evolution of land acquisition law in India will likely require continued refinement and adaptation to address emerging challenges related to urbanization, environmental sustainability, technological change, and evolving constitutional jurisprudence. The fundamental principles established by the LARR Act – transparency, participation, fair compensation, and comprehensive rehabilitation – provide a solid foundation for this ongoing evolution, but their practical implementation will require sustained attention to institutional capacity, procedural innovation, and stakeholder engagement.

The comparative analysis of the Land Acquisition Act, 1894 and LARR Act, 2013 demonstrates not only the progress made in protecting landowner rights and promoting social justice but also the persistent challenges in reconciling individual property rights with collective development goals in a diverse and rapidly changing society. As India continues its development trajectory, the lessons learned from both the failures of the 1894 Act and the implementation challenges of the LARR Act will be crucial for designing effective and equitable land acquisition policies for the future.

References

[1] The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2121?locale=en

[2] Drishti IAS. Land Acquisition in India – Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_acquisition_in_India

[3] Indian Kanoon. The Land Acquisition Act, 1894. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/7832/

[4] Legal Service India. Right To Property And Judicial Findings Article 300-A. Available at: https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-2067-right-to-property-and-judicial-findings-article-300-a.html

[5] Law Bhoomi. Article 300A of Constitution of India. Available at: https://lawbhoomi.com/article-300a-of-constitution-of-india/

[6] Supreme Court Observer. Indore Development Authority v Manoharlal Land Acquisition Case Background. Available at: https://www.scobserver.in/cases/indore-development-authority-manoharlal-land-acquisition-case-background/

[7] Live Law. Seven Sub-Rights of Right to Property Under Article 300A of Constitution Supreme Court Explains. Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/supreme-court/seven-sub-rights-of-right-to-property-under-article-300a-of-constitution-supreme-court-explains-258140

[8] iPleaders. The Land Acquisition Act, 2013. Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/the-land-acquisition-act-2013/

[9] JURIST. India Supreme Court outlines requirements for state acquisition of private property. Available at: https://www.jurist.org/news/2024/05/india-supreme-court-outlines-requirements-for-state-acquisition-of-private-property/

Understanding the Land Acquisition Act 2013: Key Provisions and Farmer Rights

Introduction

The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 [1], commonly referred to as the Land Acquisition Act 2013 or LARR Act, represents a paradigmatic shift in India’s approach to land acquisition. This landmark legislation replaced the colonial-era Land Acquisition Act of 1894, which had governed land acquisition for nearly 120 years. The enactment of this law marked a significant departure from the state-centric approach of its predecessor towards a more balanced framework that recognizes the rights of landowners while accommodating development needs.

The Act came into force on January 1, 2014, fundamentally altering the landscape of land acquisition in India. Its primary objective centers on ensuring fair compensation, transparency, and adequate rehabilitation for those affected by land acquisition. The legislation emerged as a response to widespread criticism of the 1894 Act, which was perceived as heavily skewed in favor of the state and development agencies at the expense of landowner rights.

Historical Context and Legislative Evolution

The colonial Land Acquisition Act of 1894 was enacted during British rule with the primary purpose of facilitating government acquisition of private land for public purposes. However, this legislation was characterized by minimal compensation provisions, lack of transparency, and absence of rehabilitation measures for affected persons. The doctrine of eminent domain, which empowers the sovereign to acquire private property for public use, formed the foundation of the 1894 Act [2].

The inadequacies of the 1894 Act became increasingly apparent in independent India, particularly in cases such as the Nandigram and Singur incidents in West Bengal, where forcible land acquisition for industrial projects led to significant social unrest. These events highlighted the urgent need for comprehensive reform in land acquisition laws to balance development imperatives with fundamental rights of citizens.

The legislative process for the 2013 Act began with the introduction of the Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Bill, 2011 in the Lok Sabha on September 7, 2011. Following extensive parliamentary debate and committee deliberations, the Bill was passed by the Lok Sabha on August 29, 2013, and by the Rajya Sabha on September 4, 2013, receiving presidential assent subsequently.

Fundamental Principles and Scope

The 2013 Act is grounded in several fundamental principles that distinguish it from its predecessor. These principles include the right to fair compensation, transparency in acquisition procedures, mandatory social impact assessment, consent requirements for certain categories of projects, and comprehensive rehabilitation and resettlement provisions.

The Act applies to all land acquisitions by the government or any entity on behalf of the government, including public-private partnerships and private companies for public purposes. However, certain acquisitions are exempted under the Fourth Schedule of the Act, including those under special enactments such as the Atomic Energy Act, 1962, the Special Economic Zones Act, 2005, and various other sector-specific legislation.

Expanded Definition of Public Purpose

One of the significant reforms introduced by the 2013 Act is the expanded and more restrictive definition of “public purpose.” Unlike the 1894 Act, which provided a broad and often subjective interpretation of public purpose, the 2013 Act specifically enumerates the purposes for which land can be acquired. These include strategic purposes relating to defense and national security, infrastructure projects such as railways, highways, and ports, planned development of villages and urban areas, residential purposes for economically weaker sections, and educational and healthcare facilities.

The Act also introduces the concept of “affected family,” which extends beyond mere landowners to include anyone whose primary source of livelihood is likely to be affected by the acquisition. This inclusive definition recognizes the interdependent nature of rural economies and ensures that all stakeholders impacted by land acquisition receive appropriate consideration and compensation.

Social Impact Assessment Framework

A cornerstone of the 2013 Act is the mandatory Social Impact Assessment (SIA) requirement for all land acquisitions [3]. The SIA serves as a comprehensive evaluation mechanism to assess the potential social, economic, and environmental impacts of proposed acquisitions on affected communities. This assessment must be conducted by qualified experts and institutions, ensuring scientific rigor in the evaluation process.

The SIA process involves several critical components, including baseline surveys of affected areas, consultation with affected families and local communities, assessment of impact on livelihoods and social infrastructure, evaluation of environmental consequences, and recommendation of mitigation measures. The assessment must be conducted in consultation with Panchayati Raj institutions and local communities, ensuring participatory decision-making.

Upon completion, the SIA must be made public and subjected to public hearings in affected areas. These hearings provide a forum for affected communities to voice their concerns and suggestions, contributing to more informed decision-making. The SIA must be approved by an Expert Group constituted at the state level before land acquisition can proceed.

However, the Act provides exemptions from SIA requirements for certain categories of projects, including those related to national defense and security, linear infrastructure projects such as railways and highways, and projects for affected families in the same district. These exemptions reflect the legislature’s recognition of the urgent nature of certain public purposes while maintaining the general principle of impact assessment.

Consent Requirements and Democratic Participation

The 2013 Act introduces unprecedented consent requirements for land acquisition, representing a fundamental shift towards democratic participation in acquisition decisions [4]. For acquisitions involving public-private partnerships, the consent of at least 70% of affected families is mandatory. For acquisitions by private companies, this threshold increases to 80% of affected families.

These consent requirements apply specifically to projects undertaken in partnership with or by private entities, reflecting the legislature’s intent to provide additional protection when private commercial interests are involved. Government projects for purely public purposes do not require such consent, recognizing the sovereign power of the state to acquire land for genuine public needs.

The consent mechanism operates through a structured process involving individual consent collection, verification by appropriate authorities, and documentation of the consent process. Affected families have the right to withdraw consent until the preliminary notification stage, ensuring that consent is truly voluntary and informed.

Enhanced Compensation Framework

The compensation provisions of the 2013 Act represent a quantum leap from the inadequate compensation mechanisms of the 1894 Act. The new framework ensures that affected landowners receive compensation that is significantly higher than market value, acknowledging the forced nature of acquisition and the need to enable affected persons to restore their livelihoods.

For rural areas, compensation is set at four times the market value of the land, while for urban areas, it is twice the market value. Additionally, a solatium of 100% of the market value is payable, effectively doubling the base compensation. Market value is determined based on the highest sale price of similar land in the vicinity during the three years preceding the preliminary notification.

The Act also provides for additional compensation in cases where acquired land is subsequently sold by the acquiring authority at a higher price. If such sale occurs within five years of acquisition, the original landowners are entitled to a share of the enhanced value, ensuring that they benefit from any appreciation in land value resulting from development.

For agricultural land, the Act recognizes the income-generating potential of the land and provides additional benefits, including annuity payments to affected families based on the agricultural income from the land. This provision acknowledges that land is not merely an asset but a source of livelihood for farming communities.

Rehabilitation and Resettlement Provisions

The 2013 Act establishes comprehensive rehabilitation and resettlement (R&R) provisions that were entirely absent from the 1894 Act [5]. These provisions recognize that displacement involves more than loss of land and encompasses disruption of social networks, cultural practices, and economic systems.

The R&R framework includes several key components. For housing, each affected family losing a house is entitled to a house in the resettlement area or compensation equivalent to the value of the house lost. For employment, efforts must be made to provide employment opportunities or skill development for at least one member of each affected family. Infrastructure in resettlement areas must include basic amenities such as roads, water supply, electricity, sanitation, schools, and healthcare facilities.

Special provisions exist for vulnerable groups, including Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and other marginalized communities, who receive additional support and preferential treatment in rehabilitation programs. The Act also mandates the establishment of a Rehabilitation and Resettlement Committee for each project to monitor and oversee the implementation of R&R measures.

Procedural Safeguards and Transparency Measures

The 2013 Act introduces numerous procedural safeguards to ensure transparency and accountability in the acquisition process. All notifications and documents related to acquisition must be published in local languages and made easily accessible to affected communities. Public hearings are mandatory at various stages of the acquisition process, providing multiple opportunities for community participation.

The Act establishes clear timelines for various stages of acquisition, preventing indefinite delays that characterized acquisitions under the 1894 Act. For instance, awards must be made within twelve months of the preliminary notification, ensuring expeditious completion of the acquisition process while maintaining due process safeguards.

Environmental impact assessments are required where applicable, ensuring that ecological considerations are integrated into acquisition decisions. The Act also mandates consultation with local self-government institutions, recognizing their role in local governance and development planning.

Section 24 and Transitional Provisions

Section 24 of the 2013 Act addresses the critical issue of transitional arrangements for acquisitions that were pending under the 1894 Act when the new law came into force [6]. This provision has been the subject of extensive litigation and judicial interpretation, making it one of the most litigated sections of the Act.

Under Section 24(1), acquisitions where no award had been made under Section 11 of the 1894 Act would continue under the old procedures, but compensation would be determined according to the enhanced provisions of the 2013 Act. Where awards had already been made, acquisitions would continue under the 1894 Act as if it had not been repealed.

Section 24(2) provides for lapsing of acquisitions where awards were made five years or more before the commencement of the 2013 Act, but physical possession had not been taken or compensation had not been paid. This provision was designed to address cases where acquisition proceedings had become stale due to administrative inaction.

The Supreme Court’s interpretation of Section 24 in landmark cases such as Indore Development Authority v. Manoharlal [7] has clarified that land acquisition proceedings lapse only if both conditions—non-payment of compensation and non-taking of possession—are satisfied. The Court has held that mere tender or offer of compensation satisfies the payment requirement, even if landowners refuse to accept it.

Recent Judicial Developments

The Supreme Court of India has played a crucial role in interpreting and clarifying the provisions of the 2013 Act through various landmark judgments. In Kolkata Municipal Corporation v. Bimal Kumar Shah [8], decided in May 2024, the Court laid down seven constitutional tests for land acquisition, emphasizing procedural safeguards under Article 300A of the Constitution.

These seven tests include the right to notice before acquisition, the right to be heard during the process, the right to review acquisition decisions, the right to appeal, the right to fair compensation, the right to due process, and the right to conclusion of acquisition proceedings. This judgment reinforces the constitutional foundation of property rights and establishes minimum procedural standards for all land acquisitions.

In recent developments, the Supreme Court has emphasized that landowners are entitled to current market value when compensation is delayed, recognizing the impact of inflation and market appreciation on compensation adequacy. The Court has also clarified that the burden of proof regarding compliance with procedural requirements lies with the acquiring authority.

State-Level Implementations and Variations

While the 2013 Act provides a central framework, several states have enacted amendments or parallel legislation to address local conditions and priorities. However, these state-level modifications have sometimes diluted the protective provisions of the central Act, leading to legal challenges and concerns about the erosion of landowner rights.

Six BJP-ruled states have enacted amendments that exempt certain categories of projects from consent and SIA requirements, effectively circumventing the central Act’s protective provisions [9]. These amendments have been criticized for undermining the democratic and participatory elements of the 2013 Act.

The Gujarat Amendment Act of 2016 exemplifies this trend, removing consent requirements for several categories of projects and reducing the scope of SIA. Similar amendments in other states have raised concerns about the federal structure of land acquisition law and the potential for a race to the bottom in terms of landowner protection.

Challenges in Implementation

Despite its progressive provisions, the 2013 Act faces several implementation challenges that limit its effectiveness. Administrative capacity constraints affect the quality and timeliness of SIA processes, with many states lacking qualified professionals and institutions to conduct proper assessments. Bureaucratic delays in various stages of acquisition continue to plague the system, despite statutory timelines.

Financial constraints at the state level pose significant challenges, as the enhanced compensation and R&R provisions require substantial resources that many state governments struggle to mobilize. This has led to delays in acquisition projects and, in some cases, abandonment of planned acquisitions.

The consent requirement, while democratically sound, has proven challenging to implement in practice, particularly for large-scale projects involving numerous landowners. The process of obtaining consent from 70-80% of affected families can be time-consuming and complex, leading to project delays and increased costs.

Coordination between various agencies involved in acquisition, rehabilitation, and resettlement remains problematic, with unclear jurisdictional boundaries and overlapping responsibilities leading to inefficiencies and gaps in implementation.

Impact on Development Projects

The 2013 Act has had a significant impact on development projects across India, with both positive and negative consequences. On the positive side, the Act has reduced conflicts and litigation in many cases by ensuring fair compensation and participatory decision-making. Many landowners who previously resisted acquisition have been more willing to cooperate when offered fair compensation and adequate rehabilitation.

However, the Act has also led to increased costs and timelines for development projects. The enhanced compensation provisions, combined with R&R requirements, have substantially increased the financial burden of land acquisition. Major infrastructure projects have experienced delays due to the time required for SIA processes and consent collection.

Some developers and government agencies have sought alternative strategies, including land pooling and development agreements, to avoid the complexities of the 2013 Act. While these alternatives can be mutually beneficial, they may not always provide the same level of protection for landowners as formal acquisition under the Act.

Regulatory Framework and Institutional Mechanisms

The 2013 Act establishes several institutional mechanisms to ensure effective implementation and oversight. The Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Authority is constituted at the state level to hear disputes and appeals related to acquisition, compensation, and rehabilitation. This quasi-judicial body provides an accessible forum for redressal of grievances.

The Administrator for Rehabilitation and Resettlement is appointed for each acquisition project to oversee the implementation of R&R measures and ensure compliance with statutory requirements. This official serves as a single point of accountability for rehabilitation activities.

The National Land Acquisition and Rehabilitation and Resettlement Authority may be established by the central government to coordinate policies and provide technical support to state-level institutions. While this central authority has not been fully operationalized, its potential establishment reflects the need for national coordination in land acquisition matters.

Future Directions and Reforms

The 2013 Act continues to evolve through judicial interpretation, administrative implementation, and potential legislative amendments. Several areas require attention to improve the Act’s effectiveness and address implementation challenges.

Streamlining administrative procedures while maintaining substantive protections remains a key challenge. This could involve standardization of SIA methodologies, development of digital platforms for consent collection and processing, and capacity building for implementing agencies.

Clarification of ambiguous provisions through legislative amendments or authoritative guidelines could reduce litigation and improve implementation consistency. Areas requiring clarification include the definition of “affected family,” the scope of consent requirements, and the methodology for determining market value.

Integration of the 2013 Act with other land and development laws could improve coordination and reduce conflicts between different legal frameworks. This includes alignment with environmental laws, forest laws, and urban planning legislation.

Conclusion

The Land Acquisition Act 2013 represents a significant advancement in India’s approach to balancing development needs with individual rights and social justice. While the Act faces implementation challenges and has been subject to dilution through state-level amendments, its fundamental principles of fair compensation, transparency, and participatory decision-making remain vital for ensuring equitable development.

The Act’s emphasis on social impact assessment, consent requirements, and comprehensive rehabilitation has transformed the discourse around land acquisition from a purely administrative process to one that recognizes the human and social dimensions of displacement. The enhanced compensation provisions, while increasing the cost of acquisition, ensure that affected persons are better equipped to rebuild their lives and livelihoods.

As India continues its rapid development trajectory, the effective implementation of the 2013 Act becomes crucial for maintaining social harmony and ensuring that the benefits of development are shared equitably. The challenge lies in streamlining procedures and building administrative capacity while preserving the Act’s protective provisions and democratic principles.

The evolution of land acquisition law in India, from the colonial 1894 Act to the progressive 2013 legislation, reflects the country’s journey toward a more inclusive and rights-based approach to development. The continued refinement and effective implementation of this framework will be essential for India’s sustainable and equitable growth in the years to come.

References

[1] Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, Act No. 30 of 2013. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Right_to_Fair_Compensation_and_Transparency_in_Land_Acquisition,_Rehabilitation_and_Resettlement_Act,_2013

[2] Doctrine of Eminent Domain in Land Acquisition – Constitutional Foundation and Legal Framework. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_acquisition_in_India

[3] Social Impact Assessment Framework under LARR Act 2013 – Implementation Guidelines and Procedures. Available at: https://lawforeverything.com/land-acquisition-act-2013/

[4] Consent Requirements in Land Acquisition – Democratic Participation and Legal Safeguards. Available at: https://www.legalkart.com/legal-blog/understanding-the-land-acquisition-act-2013-a-comprehensive-guide

[5] Rehabilitation and Resettlement Provisions under Land Acquisition Act 2013. Available at: https://restthecase.com/knowledge-bank/larr-act

[6] Section 24 LARR Act – Transitional Provisions and Supreme Court Interpretation. Available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2022/06/13/section-24-of-land-acquisition-act-2013-and-doctrine-of-finality-an-overview/

[7] Indore Development Authority v. Manoharlal, Supreme Court of India, 2020. Available at: https://www.scobserver.in/cases/indore-development-authority-manoharlal-land-acquisition-case-background/

[8] Kolkata Municipal Corporation v. Bimal Kumar Shah, Supreme Court of India, 2024. Available at: https://cjp.org.in/supreme-court-lays-down-7-constitutional-tests-for-land-acquisition/

[9] State-Level Amendments to Land Acquisition Laws – Analysis of BJP-Ruled States. Available at: https://cjp.org.in/land-acquisition-act/

Bail on Humanitarian Grounds in NDPS Case: Rajasthan High Court’s Landmark Ruling

Introduction

The evolving landscape of criminal jurisprudence in India has witnessed a significant shift towards a more humanitarian approach to justice, balancing the imperatives of law enforcement with the fundamental principles of human dignity and compassion. A recent landmark decision by the Rajasthan High Court in the case of Bhawani Pratap Singh v. State of Rajasthan exemplifies this progressive judicial approach, where the Court granted bail on humanitarian grounds in an NDPS case, allowing temporary release to an accused under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act [1]. This decision underscores the principle that the objective of criminal justice is not merely punitive but reformative and humane, reflecting a broader constitutional commitment to human rights and social welfare.