Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

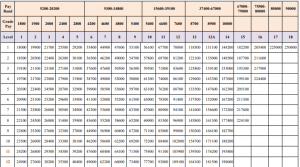

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

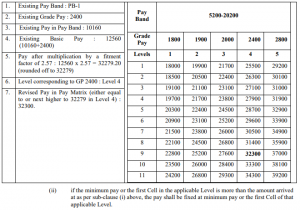

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

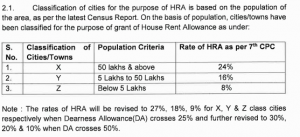

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

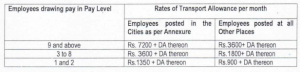

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Personality Rights in India: Legal Framework and Judicial Evolution

Introduction

The digital revolution has fundamentally transformed how celebrity identity is commodified, exploited, and protected in contemporary society. In recent years, Indian courts have witnessed an unprecedented surge in litigation concerning the unauthorized use of celebrity personas, particularly through emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and deepfake mechanisms. The Delhi High Court’s recent interventions in protecting Bollywood celebrities such as Aishwarya Rai Bachchan, Abhishek Bachchan, and filmmaker Karan Johar against unauthorized commercial exploitation represent a watershed moment in the evolution of celebrity personality rights jurisprudence in India. These judicial pronouncements signal a robust commitment to safeguarding individual autonomy over personal identity in an increasingly digitized commercial landscape.

The significance of these developments extends beyond the entertainment industry, touching fundamental questions about human dignity, economic exploitation, and the balance between commercial interests and individual rights. As technology enables increasingly sophisticated methods of replicating human likeness and voice, the legal system must adapt to protect individuals from having their identities weaponized without consent. This article examines the comprehensive legal framework governing personality rights in India, analyzes landmark judicial decisions that have shaped this doctrine, explores the regulatory mechanisms currently in place, and discusses the challenges posed by artificial intelligence in the contemporary context.

Understanding Personality Rights in India: Conceptual Foundations

Personality rights in India encompass the legal entitlements that protect an individual’s control over the commercial use of their identity attributes. These attributes include not merely physical characteristics like name, image, and voice, but extend to unique mannerisms, signature catchphrases, distinctive styles, and any other identifiable features that constitute a person’s public persona. The doctrine recognizes that an individual’s identity possesses inherent economic value, particularly for public figures and celebrities whose fame creates marketable goodwill.

The philosophical underpinning of personality rights rests on two distinct but interconnected foundations. First, the dignitary interest recognizes that every person has a fundamental right to control how their identity is presented to the world, protecting against misrepresentation, degradation, or unauthorized association with products or causes. Second, the proprietary interest acknowledges that celebrities invest significant time, effort, and resources in building their public image, creating legitimate economic interests that warrant legal protection against free-riding and unjust enrichment by third parties.

Unlike many Western jurisdictions where personality rights are codified through specific legislation, India’s approach remains predominantly common law-based, drawing from multiple legal doctrines including privacy rights, passing off, defamation, and copyright principles. This fragmented approach has both advantages and disadvantages—while allowing judicial flexibility to adapt to evolving circumstances, it also creates uncertainty and inconsistency in application across different cases and jurisdictions.

Constitutional Framework and Privacy Rights

The Indian Constitution does not explicitly enumerate personality rights as fundamental rights. However, the Supreme Court’s expansive interpretation of Article 21, which guarantees the right to life and personal liberty, has created constitutional foundations for personality rights protection in India. The watershed moment came in 1994 with the Supreme Court’s decision in R. Rajagopal v. State of Tamil Nadu [1], where the Court recognized that the right to privacy forms an intrinsic component of personal liberty under Article 21.

The Rajagopal case involved a proposed autobiography of a death row convict named Auto Shankar, which prison authorities sought to suppress. While the immediate issue concerned freedom of press versus privacy, the Court laid down seminal principles regarding personality rights in India. The judgment established that every individual possesses the right to safeguard their privacy, including control over how their personal information and identity are disseminated publicly. Crucially, the Court held that unauthorized commercial exploitation of a person’s name or likeness constitutes a violation of this constitutional right.

The Court articulated a framework balancing privacy rights against freedom of expression guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a). It held that while the press enjoys freedom to publish matters of public interest, this freedom does not extend to invading privacy for purely commercial purposes. The judgment recognized that public figures have somewhat reduced privacy expectations regarding matters of legitimate public concern, but retained full protection against unauthorized commercial appropriation of their identity.

Building upon Rajagopal, subsequent constitutional developments have reinforced personality rights. The nine-judge bench decision in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India (2017) definitively established privacy as a fundamental right, explicitly recognizing the “right to control one’s personal information” as a critical aspect of informational privacy. While this case primarily concerned data protection and government surveillance, its principles extend naturally to personality rights, as both doctrines center on individual autonomy and control over personal attributes.

Statutory Framework: Limited but Significant Protections

India lacks dedicated legislation specifically addressing personality rights, instead relying on provisions scattered across various intellectual property and commercial statutes. This patchwork approach requires creative legal interpretation to provide adequate protection.

The Trade Marks Act, 1999 offers indirect protection through the doctrine of passing off under common law, codified in Section 27(2). While primarily designed to prevent consumer confusion regarding goods and services, courts have extended passing off principles to protect celebrity identities. When a third party uses a celebrity’s name or likeness in a manner suggesting endorsement or association, this may constitute actionable passing off even absent trademark registration. The critical requirement is demonstrating goodwill and reputation that the unauthorized use seeks to exploit.

The Copyright Act, 1957 provides limited protection for certain personality attributes. Section 57 grants performers moral rights over their performances, including the right to prevent distortion or mutilation that would harm their honor or reputation. Section 38-B, introduced through the 2012 amendment, specifically addresses performers’ rights to broadcast and communication of their performances. While these provisions primarily target unauthorized reproduction of performances rather than identity per se, recent cases like Arijit Singh v. Codible Ventures LLP have successfully invoked these provisions in personality rights disputes [2].

The Information Technology Act, 2000, though not designed for personality rights protection, has become relevant in addressing digital violations. Section 66E criminalizes violation of privacy through intentional capture, publication, or transmission of images of private areas without consent. Section 66D addresses punishment for cheating by personation using computer resources. While these provisions primarily target privacy and identity theft rather than commercial exploitation, they establish the legal framework recognizing digital identity as worthy of protection.

Judicial Development: Landmark Cases Shaping Personality Rights in India

Indian courts have played the defining role in developing personality rights doctrine through progressive judgments that have expanded protection incrementally. Beyond the foundational Rajagopal decision, several cases merit detailed examination for their contribution to this evolving jurisprudence.

The Madras High Court’s decision concerning actor Rajinikanth established important precedents regarding the threshold for proving personality rights violations. The Court held that when a celebrity’s identity is sufficiently distinctive and recognized, unauthorized commercial use need not demonstrate consumer confusion or deception. The mere appropriation of the celebrity’s identity attributes for commercial gain, without consent, constitutes actionable wrong. This departure from traditional passing off requirements significantly strengthened personality rights protection by eliminating the often-difficult burden of proving actual confusion.

In ICC Development (International) Ltd. v. Arvee Enterprises (2003), the Delhi High Court addressed personality rights in the context of sports marketing. While the case primarily concerned ICC’s rights to the Cricket World Cup brand, the Court’s observations about protecting individual players’ rights laid groundwork for future personality rights litigation. The judgment recognized that sportspersons develop protectable rights in their performances and public personas.

The case of Titan Industries Ltd. v. Ramkumar Jewellers (2012) saw the Delhi High Court injuncting unauthorized use of celebrity cricketer M.S. Dhoni’s image in jewelry advertisements. The Court held that Dhoni had acquired distinctive goodwill and reputation, creating protectable personality rights. Unauthorized use not only caused economic harm through lost endorsement opportunities but also violated his right to control commercial associations with his identity.

The AI Era: Recent Judicial Responses to Technological Threats

The emergence of artificial intelligence technologies capable of creating hyper-realistic deepfakes, voice clones, and digital avatars has precipitated a new wave of personality rights litigation. Courts have responded with heightened protective measures recognizing the existential threat these technologies pose to individual autonomy.

The Delhi High Court’s 2023 decision protecting actor Anil Kapoor represents a landmark in addressing AI-driven personality rights violations [3]. Kapoor approached the Court after discovering numerous instances of AI-generated deepfake videos superimposing his face onto other actors, unauthorized merchandise featuring his likeness, and websites selling fake autographs. The Court granted a sweeping ex-parte injunction restraining not only specifically identified defendants but also “the world at large” from misusing Kapoor’s personality attributes including his name, image, voice, signature catchphrases like “jhakaas,” and any AI-generated content featuring his likeness.

The Court’s reasoning emphasized several critical points. First, it recognized that personality rights exist independent of contractual arrangements or intellectual property registrations—they are inherent rights flowing from personal identity. Second, the judgment acknowledged that AI technologies democratize the ability to create convincing fake content, exponentially increasing the risk of harm. Third, the Court held that the scale and persistence of digital violations justify broader injunctions than traditional intellectual property cases, including dynamic injunctions that automatically apply to future infringers.

The Bombay High Court’s 2024 decision in Arijit Singh v. Codible Ventures LLP marked another significant milestone in protecting artists against AI voice cloning [2]. Singh sued after discovering platforms offering AI tools that could replicate his distinctive voice, allowing users to create songs apparently sung by him without permission. The Bombay High Court granted ad-interim injunction restraining the defendants from operating or promoting such voice cloning tools targeting Singh’s voice.

The Court’s analysis integrated multiple legal doctrines. It invoked the Copyright Act’s provisions on performers’ rights, holding that Singh’s voice constitutes a protected performance. The judgment recognized personality rights as protecting the commercial value of Singh’s distinctive vocal characteristics. Significantly, the Court held that merely providing tools for others to create infringing content constitutes contributory infringement, establishing potential liability for technology platforms facilitating personality rights violations.

Balancing Rights: Personality Rights versus Freedom of Expression

While courts have robustly protected personality rights, they have simultaneously recognized the critical importance of preserving freedom of expression, particularly for artistic works, parody, satire, and matters of public interest. Establishing appropriate boundaries between these competing rights remains an ongoing judicial challenge.

The Delhi High Court’s decision in DM Entertainment Pvt. Ltd. v. Baby Gift House addressed this balance in the context of Rajesh Khanna’s estate seeking protection of the late actor’s personality rights. The Court granted protection but carved out exceptions for biographical works, documentaries, and artistic expressions that reference Khanna’s life and career. The judgment emphasized that personality rights cannot be weaponized to suppress legitimate artistic or journalistic expression about public figures.

Similarly, in Digital Collectibles PTE Ltd. v. Galactus Funware Technology Pvt. Ltd., the Court distinguished between commercial exploitation and permissible uses. The judgment held that using celebrity images or references in contexts of parody, criticism, or commentary—even when the creator derives revenue—does not necessarily violate personality rights if the use is genuinely expressive rather than purely commercial. The critical inquiry focuses on whether the use exploits the celebrity’s commercial value or rather makes an independent statement about them.

Courts have adopted a multi-factor test for evaluating whether particular uses fall within protected expression. Relevant considerations include: the transformative nature of the use, whether the work comments upon or criticizes the celebrity, the extent to which the celebrity’s identity dominates the work, whether the work serves primarily as a vehicle for commercial gain versus artistic expression, and the potential for consumer confusion regarding endorsement or sponsorship.

This balancing approach reflects constitutional imperatives. Article 19(1)(a) protects not merely speech but also artistic expression, satire, and dissent. An overly expansive interpretation of personality rights could chill legitimate artistic and journalistic endeavors, creating chilling effects on cultural production. Courts therefore tread carefully, protecting personality rights against naked commercial exploitation while preserving breathing space for creative expression.

Regulatory Mechanisms and Enforcement Challenges

Enforcing personality rights in India in the digital age presents formidable practical challenges. The borderless nature of internet commerce, the anonymity afforded by digital platforms, and the sheer volume of potential infringements create significant obstacles to effective rights protection.

Traditional enforcement mechanisms include civil suits seeking injunctions and damages. Courts have shown willingness to grant ex-parte injunctions in clear-cut cases, particularly where continuing violations threaten irreparable harm. However, obtaining and enforcing judgments against online infringers, especially those operating from foreign jurisdictions, remains extremely difficult. The technical complexity of blockchain-based platforms and cryptocurrency transactions further complicates enforcement.

Platform liability has emerged as a critical issue. While the Information Technology Act’s safe harbor provisions under Section 79 protect intermediaries from liability for user-generated content if they act as passive conduits and remove infringing content upon notice, courts have shown willingness to hold platforms accountable when they actively facilitate or profit from infringement. The dynamic injunction approach adopted in cases like Anil Kapoor’s attempts to address this by requiring platforms to proactively prevent similar future violations.

Administrative enforcement through existing regulatory bodies remains limited. While the Advertising Standards Council of India provides self-regulatory oversight over advertising content, including unauthorized celebrity endorsements, its jurisdiction is limited and enforcement mechanisms lack teeth. The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology has issued guidelines and rules addressing various aspects of digital content, but these do not specifically target personality rights violations.

Criminal remedies exist for certain egregious violations. Sections 66C (identity theft) and 66D (cheating by personation) of the Information Technology Act criminalize specific digital identity crimes. However, prosecution under these provisions requires proving intent to defraud or cause harm, which may not encompass all personality rights violations motivated by commercial gain rather than malicious intent.

International Perspectives and Comparative Analysis

Examining how other jurisdictions address personality rights provides valuable insights for India’s evolving legal framework. The United States recognizes “right of publicity” through state law, with significant variations across jurisdictions. California’s statute provides robust protection extending even posthumously, allowing estates to control commercial use of deceased celebrities’ identities. Courts have developed sophisticated doctrines balancing publicity rights against First Amendment protections.

The European Union addresses personality rights through multiple instruments including the General Data Protection Regulation, which protects personal data including biometric identifiers, and various national laws protecting image rights. France, for example, recognizes strong personality rights under the Civil Code, protecting individuals’ right to control their image throughout life and limiting posthumous commercial exploitation.

The United Kingdom primarily addresses personality rights through passing off and trademark law, requiring demonstration of goodwill and misrepresentation. This approach resembles India’s but has developed more extensive case law. Recent cases have addressed social media influencers’ personality rights and digital exploitation.

Learning from these jurisdictions, India could benefit from more explicit statutory frameworks while maintaining judicial flexibility. Clear legislative standards would provide predictability for both rights holders and potential users, reducing litigation costs and fostering innovation while respecting personality rights.

Contemporary Challenges: Deepfakes, NFTs, and the Metaverse

Emerging technologies continue presenting novel challenges to personality rights protection. Deepfake technology, which uses machine learning to create synthetic media indistinguishable from authentic recordings, poses existential threats to personal autonomy and truth itself. Beyond commercial exploitation, deepfakes enable creation of non-consensual intimate imagery, political disinformation, and reputational destruction.

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and digital collectibles raise complex questions about personality rights in virtual spaces. When digital artists create and sell NFTs featuring celebrity likenesses, does this constitute protected artistic expression or commercial exploitation? Courts will need to develop nuanced approaches distinguishing transformative artistic works from mere digital merchandise.

The metaverse and virtual worlds present perhaps the most complex frontier. As individuals increasingly inhabit digital avatars and virtual identities, questions arise about personality rights in these contexts. Can celebrities prevent others from creating virtual avatars resembling them? What about AI-powered virtual influencers modeled on real persons? These questions lack clear answers under existing legal frameworks.

Voice cloning technology, as addressed in the Arijit Singh case, continues advancing rapidly. Platforms now offer tools allowing anyone to synthesize speech in celebrity voices within seconds. While legitimate applications exist—such as preserving voices of individuals with degenerative conditions—the potential for abuse is immense, ranging from fraudulent impersonation to unauthorized commercial endorsements.

The Path Forward: Recommendations for Legislative Reform

Given the challenges identified, comprehensive legislative reform appears increasingly necessary. A dedicated personality rights statute could provide clarity while maintaining flexibility to address evolving technologies. Such legislation should clearly define protectable personality attributes, establish registration mechanisms for those seeking heightened protection, specify exceptions for legitimate uses including news reporting, artistic expression, parody, and satire, and provide effective remedies including injunctions, damages, and statutory penalties for willful violations.

The statute should address temporal limitations, particularly regarding posthumous personality rights. While some protection for deceased personalities’ estates may be appropriate given ongoing commercial value, unlimited perpetual protection risks removing public domain material and hampering creative expression. A balanced approach might provide limited posthumous protection, perhaps 50-70 years, similar to copyright terms.

Platform accountability must be strengthened. Legislation should clarify intermediary liability standards, requiring platforms to implement robust content moderation systems, respond promptly to takedown notices, and potentially employ proactive measures like AI-driven detection of likely infringing content. Safe harbor protections should be contingent on demonstrable good faith efforts to prevent infringement.

Creating specialized adjudicatory mechanisms could expedite dispute resolution. Personality rights disputes often require technical expertise regarding digital technologies and quick resolution to prevent ongoing harm. Specialized tribunals or fast-track procedures within existing intellectual property forums could provide efficient remedies.

Conclusion

India’s personality rights jurisprudence stands at a critical juncture. Judicial decisions over the past three decades have constructed a robust framework protecting individuals’ autonomy over their identities, with recent cases responding proactively to technological threats posed by artificial intelligence and deepfakes. The Delhi High Court’s protection of Anil Kapoor [3] and the Bombay High Court’s decision in Arijit Singh’s favor [2] demonstrate judicial recognition that traditional legal doctrines must adapt to digital realities.

However, the absence of comprehensive statutory frameworks creates uncertainty and risks inconsistent application across jurisdictions. As technology continues advancing, enabling ever-more sophisticated methods of identity appropriation and manipulation, the need for clear legislative standards becomes increasingly urgent. Such legislation must carefully balance personality rights protection against freedom of expression, ensuring that legitimate artistic, journalistic, and public interest uses remain permissible while preventing commercial exploitation and malicious misuse.

The stakes extend beyond celebrity endorsements and commercial interests. Personality rights implicate fundamental questions of human dignity, autonomy, and identity in an increasingly digital world. As artificial intelligence blurs boundaries between authentic and synthetic, protecting individuals’ control over their own identities becomes essential to preserving meaningful human agency. India’s legal system must continue evolving to meet these challenges, combining judicial innovation with thoughtful legislative reform to create a framework protecting personality rights for all citizens, not merely the famous few.

References

[1] R. Rajagopal v. State of Tamil Nadu, AIR 1995 SC 264. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/501107/

[2] SpicyIP. (2024). Synthetic Singers and Voice Theft: BomHC protects Arijit Singh’s Personality Rights. Available at: https://spicyip.com/2024/08/synthetic-singers-and-voice-theft-bomhc-protects-arijit-singhs-personality-rights-part-i.html

[3] LiveLaw. (2023). Delhi High Court Protects Actor Anil Kapoor’s Personality Rights, Restrains Misuse Of His Name, Image Or Voice Without Consent. Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/delhi-high-court-anil-kapoor-voice-image-misuse-personality-rights-238217

[4] World Intellectual Property Organization. (2024). AI voice cloning: how a Bollywood veteran set a legal precedent. Available at: https://www.wipo.int/web/wipo-magazine/articles/ai-voice-cloning-how-a-bollywood-veteran-set-a-legal-precedent-73631

[5] The IP Press. (2023). Delhi High Court’s Landmark Order: Protecting Anil Kapoor’s Persona in the Age of AI. Available at: https://www.theippress.com/2023/10/09/delhi-high-courts-landmark-order-protecting-anil-kapoors-persona-in-the-age-of-ai-an-indian-legal-perspective/

[6] Indian Kanoon. R. Rajagopal v. State of Tamil Nadu Full Judgment. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/501107/

[7] Business Standard. (2023). Delhi HC restrains use of Anil Kapoor’s name, image, signature catchphrase. Available at: https://www.business-standard.com/india-news/delhi-hc-restrains-use-of-anil-kapoor-s-name-image-signature-catchphrase-123092001237_1.html

[8] The IP Press. (2024). Voice Theft in the Digital Age: Bombay High Court’s Landmark Ruling on AI and Personality Rights. Available at: https://www.theippress.com/2024/09/05/voice-theft-in-the-digital-age-bombay-high-courts-landmark-ruling-on-ai-and-personality-rights/

[9] SCC Online. (2024). Bombay HC grants ad-interim injunction in favour of Arijit Singh to protect his personality rights. Available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2024/08/02/bomhc-grants-ad-interim-injunction-to-arijit-singh-to-protect-his-personality-rights/

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Framework and Thermal Power Plant Regulatory Changes in India: Environmental Law Developments

Introduction

India’s environmental regulatory landscape has witnessed significant transformations in recent years, particularly with the introduction of robust Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) frameworks and evolving regulations for thermal power plants. The Environment Protection (Extended Producer Responsibility) Rules, 2024, represent a paradigm shift in waste management policy, while concurrent developments in thermal power plant regulations reflect the government’s attempt to balance environmental protection with energy security concerns [1]. These developments mark a critical juncture in India’s environmental governance, establishing new accountability mechanisms for producers while addressing practical challenges faced by the power sector.

The regulatory framework encompassing these changes draws its authority from the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, which provides the foundational legal basis for environmental rule-making in India. Under Section 3 of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, the central government possesses wide-ranging powers to take measures for protecting and improving environmental quality [2]. This statutory authority has enabled the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) to introduce sweeping changes in both waste management and pollution control domains.

Extended Producer Responsibility: Legal Framework and Implementation

Constitutional and Statutory Basis

The Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) framework in India derives its constitutional legitimacy from Article 48-A of the Constitution, which mandates the state to protect and improve the environment. The Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, enacted under Article 253 read with Entry 13 of List I of the Seventh Schedule, empowers the central government to frame rules for environmental protection [3]. The Supreme Court of India, in M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (1987) 1 SCC 395, established the principle that environmental protection is a fundamental duty of both the state and citizens, providing judicial backing for stringent environmental regulations.

The EPR concept was first introduced in India through the e-Waste (Management and Handling) Rules, 2011, which recognized producers’ responsibility for managing electronic waste [4]. This foundational framework was subsequently expanded to cover plastic waste through the Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016, and has now evolved into the Environment Protection (Extended Producer Responsibility) Rules, 2024.

The Environment Protection (Extended Producer Responsibility) Rules, 2024

The Environment Protection (Extended Producer Responsibility) Rules, 2024, notified under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, establish a mandatory framework requiring Producers, Importers, and Brand Owners (PIBOs) to take responsibility for the entire lifecycle of their products. Rule 3 of the 2024 Rules defines EPR as “a policy approach in which a producer’s responsibility for a product is extended to the post-consumer stage of a product’s life cycle” [5].

The Rules impose ambitious recycling targets on PIBOs. Under Rule 6, producers must ensure that 70% of waste generated from their products is recycled or reused by 2026-27, with this target increasing to 100% by 2028-29 [6]. This progressive target structure represents a significant escalation from previous waste management requirements and reflects the government’s commitment to achieving circular economy objectives.

Rule 4 establishes the scope of application, covering packaging materials made of paper, metal, glass, and plastic, as well as sanitary products. The Rules mandate that PIBOs must obtain EPR authorization from the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) or State Pollution Control Boards (SPCBs) before commencing operations. The authorization process, detailed in Rule 7, requires producers to submit detailed waste management plans and demonstrate their capacity to meet prescribed targets.

Regulatory Mechanisms and Compliance Requirements

The Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) framework operates through a credit-based system administered by the Centralized Extended Producer Responsibility Portal for Plastic Packaging, managed by the CPCB [7]. Under this system, producers can fulfill their obligations through direct collection and recycling or by purchasing EPR credits from recyclers. Rule 9 mandates that all transactions must be recorded on the centralized portal, ensuring transparency and accountability in the system.

The penalty provisions under Rule 15 establish strict consequences for non-compliance. Violations can result in closure of operations, cancellation of authorization, and financial penalties up to Rs. 1 crore. The Rules also provide for environmental compensation, calculated based on the environmental damage caused by non-compliance.

State governments play a crucial role in implementation through their respective SPCBs. Rule 12 empowers state authorities to monitor compliance, conduct inspections, and take enforcement action against violators. This decentralized approach ensures that implementation can be tailored to local conditions while maintaining national standards.

Thermal Power Plant Regulations: Recent Developments and Relaxations

Emission Norms and Compliance Timeline Extensions

Thermal power plants in India operate under emission norms prescribed under the Environment (Protection) Rules, 1986, as amended from time to time. The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change has periodically revised these norms to align with international standards and address air pollution concerns. However, implementation has faced significant challenges, leading to multiple deadline extensions.

In 2015, the MoEFCC notified revised emission norms for thermal power plants, setting stricter limits for particulate matter, sulfur dioxide (SO₂), and nitrogen oxides (NOₓ). The original compliance deadline of December 2017 has been extended multiple times, with the most recent extension granted in early 2025, pushing the deadline to 2028 for older plants [8].

The National Green Tribunal, in Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti v. Union of India, OA No. 25/2014, had earlier directed strict compliance with emission norms. However, the practical challenges faced by power utilities, including financial constraints and technical difficulties in retrofitting older plants, have necessitated a more flexible approach from regulators.

Flue Gas Desulfurization (FGD) Norms and Recent Relaxations

The requirement for installing Flue Gas Desulfurization (FGD) systems has been a contentious issue in the thermal power sector. The revised norms mandate that all thermal power plants install FGD systems to reduce SO₂ emissions. However, recent regulatory developments have introduced flexibility in implementation.

The Ministry of Power, in consultation with the MoEFCC, announced relaxations in FGD norms in July 2025, allowing plants to adopt alternative compliance mechanisms based on site-specific conditions and air quality parameters [9]. This recalibration of norms is expected to reduce electricity costs by 25-30 paise per unit, providing relief to both consumers and state electricity boards.

The relaxations are not uniform but are based on scientific assessment of ambient air quality and the specific contribution of individual plants to regional pollution levels. Plants located in areas with better air quality or those with lower capacity utilization factors may be eligible for modified compliance requirements.

Renewable Generation Obligation for Thermal Plants

A significant development in thermal power plant regulation is the introduction of Renewable Generation Obligation (RGO) for new plants. The Ministry of Power, through amendments to the Electricity Rules, 2005, has mandated that new coal or lignite-based thermal power plants must generate a portion of their total energy from renewable sources.

Under the RGO framework, thermal power plants with commercial operation dates after April 1, 2023, must meet specific renewable energy generation targets. Plants with COD between April 1, 2023, and March 31, 2025, were required to comply by April 1, 2025, while plants commissioned after April 1, 2025, must comply from their COD [10].

This regulatory innovation reflects the government’s strategy to integrate renewable energy into the traditional thermal power framework, facilitating a gradual transition toward cleaner energy generation while maintaining grid stability and energy security.

Judicial Interpretations and Case Law Developments

Supreme Court Precedents on Environmental Compliance

The Supreme Court of India has consistently emphasized strict environmental compliance in the power sector. In Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union of India (1996) 5 SCC 647, the Court established the “polluter pays” principle as a fundamental aspect of environmental law. This principle underlies both EPR frameworks and thermal power plant regulations, requiring polluters to bear the cost of environmental remediation.

In T.N. Godavarman Thirumulkpad v. Union of India (2006) 1 SCC 1, the Supreme Court reinforced the precautionary principle, mandating that environmental protection measures should not be delayed on grounds of scientific uncertainty. This precedent has been instrumental in justifying stringent EPR requirements despite industry concerns about implementation challenges.

The Court’s decision in Indian Council for Enviro-Legal Action v. Union of India (1996) 3 SCC 212 established the absolute liability principle for environmental damage, making it clear that industries cannot escape liability for environmental harm on grounds of technical impossibility or economic hardship.

National Green Tribunal Decisions

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) has played a pivotal role in shaping environmental compliance requirements. In Centre for Public Interest Litigation v. Union of India, Application No. 41/2012, the NGT directed the implementation of stricter emission norms for thermal power plants and mandated regular monitoring of compliance.

The Tribunal’s order in Social Action for Forest and Environment v. Union of India, OA No. 580/2017, specifically addressed EPR implementation, directing the CPCB to establish robust monitoring mechanisms and ensure effective enforcement of producer responsibility obligations.

Regulatory Authorities and Implementation Mechanisms

Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) Role

The CPCB serves as the apex regulatory authority for implementing both EPR and thermal power plant regulations. Under the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, and the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981, the CPCB possesses comprehensive powers to monitor, regulate, and enforce environmental compliance.

The Board’s functions include granting EPR authorizations, operating the centralized EPR portal, conducting compliance audits, and coordinating with state-level authorities. The CPCB’s technical guidelines for EPR implementation provide detailed procedures for registration, target calculation, and credit trading mechanisms.

For thermal power plants, the CPCB maintains the national database of emission monitoring data and conducts regular inspections to ensure compliance with prescribed norms. The Board’s annual reports on environmental compliance provide critical insights into sector-wide performance and identify areas requiring regulatory intervention.

State Pollution Control Boards (SPCBs)

State Pollution Control Boards function as the primary implementing agencies at the state level. Under the delegated authority from central regulations, SPCBs issue consent to establish and consent to operate permissions for industrial facilities, including thermal power plants and waste processing facilities.

The SPCBs’ responsibilities include local monitoring of EPR compliance, collection of environmental compensation, and coordination with municipal authorities for waste management infrastructure development. The effectiveness of EPR implementation largely depends on the capacity and resources of state-level institutions.

Economic Implications and Industry Response

Financial Impact on Producers

The Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) framework imposes significant compliance costs on producers, importers, and brand owners. Industry estimates suggest that EPR compliance costs range from 1-3% of product value, depending on the product category and packaging materials used. Large multinational companies have generally adapted to EPR requirements more readily than small and medium enterprises, creating potential market consolidation effects.

The credit trading system provides flexibility but also introduces market dynamics that can affect compliance costs. EPR credit prices fluctuate based on supply and demand, with recycling capacity constraints driving up costs during peak compliance periods.

Power Sector Financial Implications

The relaxation of FGD norms for thermal power plants is expected to provide financial relief to the power sector, which has been grappling with stressed assets and high non-performing loans. The estimated reduction in electricity costs by 25-30 paise per unit could improve the financial viability of thermal power plants and reduce the burden on state electricity boards.

However, the introduction of RGO requirements adds new compliance costs for thermal power plants, requiring investment in renewable energy infrastructure or purchase of renewable energy credits. This dual regulatory approach reflects the government’s balancing act between immediate financial relief and long-term environmental objectives.

International Comparisons and Best Practices

Global EPR Models

India’s EPR framework draws inspiration from international models, particularly the European Union’s Extended Producer Responsibility Directive and similar frameworks in countries like Germany, Japan, and Canada. However, the Indian model incorporates unique features such as centralized credit trading and progressive target structures that reflect local conditions and development priorities.

The integration of digital platforms for monitoring and compliance represents an innovative approach that could serve as a model for other developing countries. The real-time tracking of waste flows and recycling activities through the centralized portal enhances transparency and reduces opportunities for non-compliance.

Thermal Power Plant Standards

International best practices in thermal power plant regulation emphasize technology-neutral approaches and performance-based standards rather than prescriptive technology requirements. India’s recent shift toward flexible compliance mechanisms aligns with this global trend while maintaining environmental protection objectives.

Future Outlook and Policy Recommendations

EPR Framework Evolution

The Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) framework is likely to expand to cover additional product categories, including textiles, pharmaceuticals, and construction materials. The success of current implementation will determine the pace and scope of such expansion. Enhanced integration with municipal solid waste management systems and improved recycling infrastructure development are critical for achieving long-term objectives.

Digital innovation, including blockchain-based tracking systems and artificial intelligence for waste stream optimization, could further enhance EPR effectiveness. The development of standardized methodologies for life cycle assessment and environmental impact quantification will support evidence-based policy refinements.

Thermal Power Plant Regulations

The future of thermal power plant regulation will likely involve greater integration of renewable energy requirements, stricter efficiency standards, and enhanced focus on water conservation. The introduction of carbon pricing mechanisms could fundamentally alter the regulatory landscape and accelerate the transition toward cleaner technologies.

Technology developments in carbon capture and storage, advanced emission control systems, and hybrid renewable-thermal systems will influence regulatory approaches. Policymakers must balance environmental objectives with energy security concerns and economic realities.

Conclusion

The recent developments in Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) frameworks and thermal power plant regulations represent a significant evolution in India’s environmental governance. The Environment Protection (Extended Producer Responsibility) Rules, 2024, establish a robust foundation for circular economy implementation, while regulatory adjustments in the thermal power sector reflect pragmatic approaches to environmental compliance.

The success of these regulatory innovations depends on effective implementation, adequate institutional capacity, and continued stakeholder engagement. The balance between environmental protection and economic development remains delicate, requiring continuous monitoring, evaluation, and adaptive management approaches.

As India pursues its climate commitments and sustainable development objectives, these regulatory frameworks will play a crucial role in shaping industrial behavior and environmental outcomes. The integration of digital technologies, market-based mechanisms, and performance-based standards represents a modern approach to environmental regulation that could serve as a model for other developing nations.

The legal foundation provided by constitutional mandates, statutory authority, and judicial precedents ensures the durability of these regulatory frameworks. However, their ultimate success will depend on effective enforcement, industry compliance, and the development of supporting infrastructure and institutions.

References

[1] Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. (2024). Environment Protection (Extended Producer Responsibility) Rules, 2024. Government of India. Available at: https://eprplastic.cpcb.gov.in/

[2] Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, Section 3. The Gazette of India. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/

[3] The Constitution of India, Article 48-A and Article 253. Available at: https://www.constitutionofindia.net/

[4] Ministry of Environment and Forests. (2011). E-waste (Management and Handling) Rules, 2011. Available at: https://testbook.com/question-answer/in-india-extended-producer-responsibility3–5f34ea35d042f30d092413f4

[5] Recykal. (2025). EPR Registration Guide in India 2025: Compliance, Process, and Sustainability. Available at: https://recykal.com/blog/epr-registration-guide-in-india-all-you-need-to-know-in-2025/

[6] Mondaq. (2024). Environment Protection (Extended Producer Responsibility) Rules, 2024: Paving The Way For Sustainable Waste Management. Available at: https://www.mondaq.com/india/waste-management/1558154/

[7] Central Pollution Control Board. Centralized EPR Portal for Plastic Packaging. Available at: https://eprplastic.cpcb.gov.in/

[8] Down To Earth. (2025). India Extends SO₂ Compliance Deadline for Thermal Power Plants Yet Again. Available at: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/pollution/thermal-power-plants-get-another-extension-for-so-compliance-norms-its-time-we-reassess-ongoing-delays

[9] Construction World. (2025). India Relaxes FGD Norms for Thermal Power Plants. Available at: https://www.constructionworld.in/energy-infrastructure/power-and-renewable-energy/india-relaxes-fgd-norms-for-thermal-power-plants/76381

Housing as a Fundamental Right Under Article 21: Supreme Court’s Role in Real Estate Regulation and Protection of Homebuyers

Introduction

The recognition of housing as a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution has evolved significantly through judicial interpretation and legislative intervention. The Supreme Court of India has consistently emphasized that the right to life enshrined in Article 21 encompasses not merely the right to exist, but the right to live with human dignity, which includes adequate shelter and housing. This judicial evolution has culminated in comprehensive regulatory frameworks designed to protect homebuyers and ensure sustainable real estate development across the country.

The intersection of constitutional rights and real estate regulation represents a critical area of Indian jurisprudence, where the apex court has repeatedly intervened to balance developmental needs with fundamental rights. The establishment of the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, 2016 (RERA), alongside various Supreme Court interventions, demonstrates the judiciary’s commitment to transforming housing from a mere commodity into a recognized fundamental entitlement.

Constitutional Foundation: Housing Under Article 21

Evolution of Article 21 Interpretation

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, which guarantees that “no person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law,” has undergone expansive judicial interpretation since the landmark Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India case in 1978 [1]. The Supreme Court has consistently held that the right to life is not merely a right to animal existence but encompasses the right to live with human dignity and all that goes along with it.

In the seminal case of Shantistar Builders v. Narayan Khimalal Totame [2], the Supreme Court explicitly recognized that the right to shelter forms part of the fundamental right to life under Article 21. The Court observed that shelter is one of the basic human needs and the state has a constitutional obligation to ensure that every citizen has access to adequate housing. This interpretation has formed the bedrock of all subsequent housing-related jurisprudence in India.

The constitutional mandate extends beyond mere acknowledgment of housing as a fundamental right; it creates positive obligations on the state to actively ensure access to housing for all citizens. This has been reinforced through various judicial pronouncements that have established housing not as a directive principle but as an enforceable fundamental right with immediate obligations on the state machinery.

Judicial Expansion of Housing Rights

The Supreme Court’s approach to housing rights has been progressively expansive, moving from passive recognition to active enforcement mechanisms. In Francis Coralie Mullin v. The Administrator, Union Territory of Delhi [3], the Court established that the right to life includes the right to basic human needs, including housing, which must be available to every citizen as a matter of constitutional guarantee.

This constitutional framework has provided the foundation for challenging inadequate housing policies, forced evictions, and substandard living conditions. The Court has emphasized that housing rights cannot be subject to the whims of administrative convenience or developmental priorities that disregard constitutional mandates. The judicial interpretation has created a robust framework where housing rights are protected against both state and private actors who might otherwise compromise these fundamental entitlements.

Real Estate Regulation Framework

The Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, 2016

The Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, 2016, represents a watershed moment in Indian real estate regulation, establishing comprehensive mechanisms to protect homebuyer interests while ensuring transparent and accountable real estate development practices. The Act was enacted following widespread malpractices in the real estate sector, including project delays, diversion of funds, and misleading advertisements that left thousands of homebuyers in distress.

Under Section 3 of RERA, no promoter can advertise, market, book, sell or offer for sale, or invite persons to purchase any plot, apartment or building in any real estate project without registering the project with the Real Estate Regulatory Authority [4]. This mandatory registration requirement ensures that all real estate projects meet specific criteria regarding approvals, land title, and financial viability before being offered to potential buyers.

The Act establishes a tripartite structure comprising the Real Estate Regulatory Authority at the state level, the Real Estate Appellate Tribunal, and the central advisory council. Section 20 of RERA mandates that 70% of amounts realized from allottees must be deposited in a separate account and used only for construction of the project and payment for the land cost [4]. This provision directly addresses the problem of fund diversion that had plagued the sector for decades.

Regulatory Authority Powers and Functions

The Real Estate Regulatory Authority established under RERA possesses extensive powers to regulate the real estate sector effectively. Under Section 35 of the Act, the Authority has the power to impose penalties up to 10% of the estimated cost of the real estate project, or in case of continuing defaults, up to 10% of the cost of the project for each month during which such default continues [4].

The Authority’s jurisdiction extends to investigating complaints, conducting inquiries, and ensuring compliance with regulatory requirements. Section 31 empowers the Authority to investigate suo-moto or on complaints regarding violations of the Act, while Section 37 provides for the recovery of interest, penalty, and compensation as land revenue, ensuring effective enforcement mechanisms.

These regulatory powers are designed to create a deterrent effect against malpractices while providing accessible remedies to aggrieved homebuyers. The Authority’s quasi-judicial powers enable it to pass orders that are binding on all parties, creating an effective dispute resolution mechanism that operates parallel to traditional civil courts but with specialized expertise in real estate matters.

Consumer Protection Integration

The integration of RERA with existing consumer protection laws has created a comprehensive framework for homebuyer protection. The Consumer Protection Act, 2019, specifically recognizes real estate services as goods and services covered under its purview, enabling consumers to approach consumer forums for redressal of grievances related to housing purchases.

This dual protection mechanism ensures that homebuyers have multiple avenues for seeking redress, whether through specialized RERA authorities or consumer protection forums. The Supreme Court has endorsed this integrated approach, recognizing that housing as a fundamental right requires multifaceted protection mechanisms that address both regulatory compliance and consumer rights simultaneously.

Supreme Court Interventions in Real Estate Sector

Landmark Judgments on Project Delays and Fund Diversion

The Supreme Court has consistently intervened in cases involving project delays and fund diversions, recognizing these as violations of fundamental rights of homebuyers. In Pioneer Urban Land and Infrastructure Limited v. Union of India [5], the Court addressed the issue of incomplete real estate projects and emphasized the need for effective regulatory mechanisms to protect homebuyer interests.

The Court has established that delayed possession of apartments amounts to deficiency in service and entitles homebuyers to compensation. This principle has been consistently applied across various cases, creating a legal framework where developers cannot escape liability for delays without valid justification. The judicial approach has transformed the real estate landscape by making developers accountable for their commitments and timelines.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court has recognized that project delays not only cause financial harm but also violate the fundamental right to housing by denying citizens access to shelter within reasonable timeframes. This constitutional perspective has elevated housing-related disputes from mere contractual matters to constitutional issues requiring urgent judicial intervention.

Retroactive Application of RERA

In a significant judgment, the Supreme Court upheld the retroactive application of RERA to ongoing projects, ensuring that even projects that commenced before the Act’s implementation would be subject to its regulatory framework [6]. This decision was crucial in ensuring that thousands of homebuyers in ongoing projects would receive protection under the new regulatory regime.

The Court reasoned that the Act’s beneficial provisions aimed at protecting homebuyers should not be denied to those who had already invested in ongoing projects. This interpretation reflected the Court’s commitment to substantive justice over procedural technicalities, ensuring that the legislative intent to protect homebuyers was given full effect regardless of the timing of project commencement.

This judicial approach has had far-reaching implications, bringing virtually the entire real estate sector under RERA’s regulatory umbrella and ensuring uniform protection for all homebuyers, regardless of when they made their investments. The decision has prevented developers from exploiting transitional provisions to escape regulatory oversight.

Enforcement of Homebuyer Rights

The Supreme Court has developed a comprehensive jurisprudence around enforcement of homebuyer rights, establishing clear remedies for various types of violations. In cases involving non-delivery of possession, the Court has consistently awarded compensation at rates that make violations commercially unviable for developers, creating strong incentives for compliance.

The Court has also addressed issues related to carpet area calculations, common area charges, and modification of approved plans, establishing clear standards that prevent developers from exploiting ambiguities in agreements to the detriment of homebuyers. These judicial interventions have created a predictable legal framework that benefits both genuine developers and homebuyers.

Stressed Real Estate Projects and Revival Mechanisms

Identification and Classification of Stressed Projects

Stressed real estate projects represent a significant challenge in the Indian real estate sector, affecting thousands of homebuyers who have invested their life savings in incomplete or delayed projects. The identification of stressed projects typically involves assessment of various factors including construction progress, financial viability, regulatory compliance, and developer credibility.

The Supreme Court has recognized that stressed projects require specialized intervention mechanisms that balance the interests of homebuyers, creditors, and other stakeholders. The Court has emphasized that while commercial considerations are important, the fundamental right to housing of homebuyers cannot be compromised in resolution processes.

Various High Courts and the Supreme Court have developed case-specific remedies for stressed projects, including appointment of monitoring committees, replacement of developers, and in extreme cases, liquidation with appropriate compensation mechanisms. These judicial interventions have prevented complete loss of homebuyer investments while ensuring that unviable projects are not allowed to continue indefinitely.

Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code Application

The application of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC) to real estate projects has created additional complexities in the resolution of stressed projects. The Supreme Court has clarified that homebuyers are financial creditors under the IBC, giving them significant rights in insolvency proceedings involving real estate developers.

In Jaypee Kensington Boulevard Apartment Welfare Association v. NBCC (India) Limited [7], the Supreme Court addressed the balance between homebuyer rights and creditor interests in insolvency proceedings. The Court emphasized that resolution plans must adequately protect homebuyer interests and cannot treat them merely as unsecured creditors.

This judicial approach has ensured that homebuyers receive priority treatment in insolvency proceedings, recognizing their dual status as both creditors and holders of fundamental rights to housing. The Court’s intervention has prevented resolution plans that would have left homebuyers without adequate protection or compensation.

Alternative Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

The Supreme Court has actively promoted alternative dispute resolution mechanisms for stressed real estate projects, recognizing that traditional litigation may not provide timely relief to distressed homebuyers. The Court has endorsed mediation and conciliation processes that can provide faster resolution while preserving the interests of all stakeholders.

These alternative mechanisms have proven particularly effective in cases where projects are commercially viable but face temporary financial constraints or management issues. The Court’s approach has enabled the completion of numerous stalled projects through negotiated settlements that ensure homebuyer protection while maintaining project viability.

Regulatory Compliance and Monitoring

State-Level Implementation Variations

The implementation of RERA across different states has shown significant variations in effectiveness and scope of regulation. While the central Act provides a uniform framework, state rules and regulations have created different standards of protection and enforcement mechanisms across jurisdictions.

The Supreme Court has noted these variations and has occasionally intervened to ensure uniform implementation of RERA provisions across states. The Court has emphasized that variations in state rules cannot dilute the fundamental protections provided under the central Act, ensuring consistent homebuyer protection regardless of geographical location.

States like Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, and Karnataka have developed comprehensive RERA rules with strong enforcement mechanisms, while some other states have been slower in establishing effective regulatory frameworks. The judicial oversight has played a crucial role in ensuring that all states meet minimum standards of homebuyer protection.

Monitoring and Compliance Mechanisms

Effective monitoring and compliance mechanisms are essential for ensuring that RERA’s objectives are achieved in practice. The Supreme Court has emphasized the need for regular monitoring of project progress, financial compliance, and adherence to promised delivery timelines.

The Court has supported the establishment of web-based monitoring systems that enable real-time tracking of project progress and compliance status. These systems have enhanced transparency and accountability while providing homebuyers with access to accurate information about their investments.

Regular auditing and inspection mechanisms have been endorsed by the Court as essential tools for preventing violations before they cause significant harm to homebuyers. The judicial approach has favored preventive rather than merely punitive measures in ensuring regulatory compliance.

Financial Protection Mechanisms

Escrow Account Requirements

Section 4(2)(l)(D) of RERA requires promoters to maintain separate accounts for each project and deposit seventy percent of amounts realized from allottees in scheduled banks [4]. This escrow account mechanism ensures that homebuyer funds are protected from diversion to other projects or purposes.

The Supreme Court has strictly enforced these escrow account requirements, treating violations as serious breaches that warrant immediate intervention. The Court has appointed monitoring committees to oversee compliance with escrow requirements in cases where violations have been detected.

These financial protection mechanisms have significantly reduced instances of fund diversion, ensuring that homebuyer investments are used exclusively for the intended projects. The judicial oversight has made these provisions more effective by ensuring swift enforcement action against violators.

Insurance and Guarantee Mechanisms

While RERA does not mandate insurance for real estate projects, the Supreme Court has encouraged the development of insurance and guarantee mechanisms that can provide additional protection to homebuyers. The Court has noted that insurance mechanisms could provide faster relief in cases of developer default or project abandonment.

Some states have explored title insurance and project completion insurance mechanisms that could provide comprehensive protection to homebuyers. The judicial support for such mechanisms has encouraged their development and adoption across various jurisdictions.

Impact Assessment and Future Directions

Effectiveness of Current Framework

The current regulatory framework combining constitutional rights recognition, RERA implementation, and judicial oversight has significantly improved homebuyer protection in India. Data from various RERA authorities shows substantial improvements in project registration, compliance with delivery timelines, and resolution of homebuyer grievances.

The Supreme Court’s active intervention has ensured that the regulatory framework operates effectively, with regular judicial review preventing regulatory capture and ensuring that homebuyer interests remain paramount. The Court’s approach has created a culture of compliance in the real estate sector.

However, challenges remain in terms of enforcement capacity, inter-agency coordination, and addressing legacy issues in pre-RERA projects. The judicial system continues to play a crucial role in addressing these challenges through case-specific interventions and systemic reforms.

Emerging Challenges and Solutions

The real estate sector continues to evolve with new challenges including technology integration, sustainability requirements, and changing consumer preferences. The Supreme Court has shown adaptability in addressing these emerging challenges while maintaining focus on fundamental homebuyer protection.

Climate change considerations and sustainable housing requirements are increasingly being recognized by the Court as integral to the right to housing as a fundamental right under Article 21. This evolution reflects the dynamic nature of constitutional interpretation and its adaptation to contemporary challenges.

The integration of digital technologies in real estate transactions and regulation presents both opportunities and challenges that require judicial guidance to ensure that technological advancement enhances rather than compromises homebuyer protection.

Conclusion

The recognition of housing as a fundamental right under Article 21 has transformed the Indian real estate landscape through a combination of constitutional interpretation, legislative intervention, and judicial oversight. The Supreme Court’s active role in protecting homebuyer interests while ensuring balanced regulation has created a framework that promotes both rights protection and sectoral growth.

The establishment of RERA, combined with consistent judicial enforcement, has significantly improved transparency, accountability, and consumer protection in the real estate sector. While challenges remain, particularly in addressing stressed projects and ensuring uniform implementation across states, the constitutional foundation and regulatory framework provide a solid basis for continued improvement.

The evolution of housing rights jurisprudence in India demonstrates the potential for constitutional provisions to drive practical improvements in citizen welfare through active judicial interpretation and enforcement. The Supreme Court’s approach has established India as a leader in constitutional protection of housing rights while maintaining a viable regulatory framework for real estate development.

Future developments will likely focus on strengthening enforcement mechanisms, addressing emerging challenges related to sustainability and technology, and ensuring that the fundamental right to housing remains accessible and meaningful for all citizens regardless of their economic status or geographical location.

References

[1] Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, AIR 1978 SC 597. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1766147/

[2] Shantistar Builders v. Narayan Khimalal Totame, AIR 1990 SC 630. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1924821/

[3] Francis Coralie Mullin v. The Administrator, Union Territory of Delhi, AIR 1981 SC 746. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/78536/

[4] Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, 2016. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2158

[5] Pioneer Urban Land and Infrastructure Limited v. Union of India, (2019) 8 SCC 416.

[6] Neelkamal Realtors Suburban Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India, (2021) 9 SCC 214. Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/supreme-court-upholds-application-of-rera-real-estate-projects-ongoing-at-acts-commencement-185419

[7] Jaypee Kensington Boulevard Apartment Welfare Association v. NBCC (India) Limited, (2021) 8 SCC 328.

RBI Digital Banking Framework 2025: Legal and Compliance Impact on Indian Banks

Executive Summary

The Reserve Bank of India has introduced groundbreaking regulatory changes in 2025 that fundamentally reshape the digital banking landscape in India. The RBI digital banking framework 2025, outlined in the Digital Banking Channels Authorisation Directions 2025 [1] released as draft guidelines in July 2025, represents a comprehensive regulatory overhaul designed to strengthen India’s digital financial ecosystem while ensuring consumer protection and systemic stability. This framework, coupled with the Digital Lending Directions 2025 [2], establishes a robust legal foundation for digital banking operations across all regulated entities.