Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

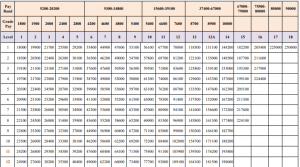

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

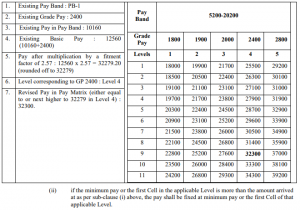

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

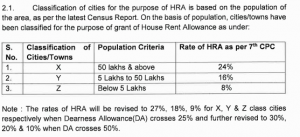

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

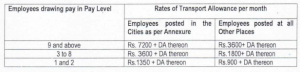

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Bail Cancellation in Women Inmates Trafficking Case under SC/ST Act: Supreme Court Landmark Decision

Introduction

In a landmark judicial decision that reinforces the protection of vulnerable populations, the Supreme Court of India cancelled the bail of a superintendent accused in a women inmates trafficking case under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989. This ruling in Victim X v. State of Bihar and Another [1] is a significant development in the jurisprudence of bail cancellation in women inmates trafficking case, strengthening both anti-trafficking measures and the special protections afforded under anti-atrocity legislation.

The case involved serious allegations against a woman superintendent of the Uttar Raksha Grih shelter home in Patna, Bihar, who was accused of facilitating the trafficking of women inmates and engaging in activities that violated their dignity and fundamental rights [2]. The Supreme Court’s intervention came after concerns were raised about the inadequate reasoning provided by the Patna High Court while granting bail to the accused.

Background and Facts of the Case

The Shelter Home System in India

India’s shelter home system operates under various legislative frameworks designed to protect vulnerable populations, particularly women and children. The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, along with state-specific regulations, governs the establishment and operation of such institutions. These facilities are meant to provide safe havens for women facing domestic violence, trafficking victims, and other vulnerable individuals seeking protection from societal harm.

The case in question involved the Uttar Raksha Grih, a women’s shelter home in Patna, Bihar, where the superintendent was entrusted with the care and protection of vulnerable women residents. The allegations against the superintendent painted a disturbing picture of betrayal of trust, where someone positioned as a protector had allegedly become an exploiter of the very individuals she was meant to safeguard.

Nature of Allegations

The charges against the superintendent encompassed serious criminal offenses including trafficking in persons, facilitation of immoral activities, and violations under the SC/ST Act. The accusations suggested a systematic exploitation of residents, many of whom belonged to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, making the case fall under the purview of special legislation designed to protect these historically marginalized communities [3].

The Supreme Court characterized the case using particularly strong language, describing it as a situation where a “savior turned into a devil,” highlighting the gravity of the breach of trust involved when someone in a position of authority exploits those under their protection [4]. This characterization underscores the court’s recognition that crimes committed by those in positions of trust warrant particularly serious consideration in bail decisions.

Legal Framework Governing Bail in SC/ST Cases

The SC/ST Act and Bail Provisions

The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, contains specific provisions regarding the grant of bail in cases involving atrocities against members of these communities. Section 18 of the Act creates stringent restrictions on the grant of anticipatory bail, reflecting the legislature’s intent to ensure that accused persons in such cases do not evade trial through pre-arrest bail provisions [5].

The 2018 amendment to the SC/ST Act further strengthened these provisions by introducing Section 18A, which mandates that no person accused of having committed an offense under this Act shall be granted anticipatory bail. This provision reflects the legislative intent to prevent the misuse of anticipatory bail provisions in cases involving atrocities against Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

Judicial Interpretation of Bail Restrictions

The Supreme Court has consistently interpreted the bail provisions under the SC/ST Act restrictively, recognizing the special vulnerability of these communities and the historical patterns of discrimination they have faced. In recent jurisprudence, including the 2025 ruling in Kiran v. Rajkumar Jivraj Jain, the Court has held that Section 18 creates a near-absolute bar on anticipatory bail in SC/ST offenses, with exceptions only where no prima facie offense under the Act is made out on the face of the FIR [6].

This restrictive approach to bail in SC/ST cases reflects the judicial recognition that members of these communities often face systemic disadvantages in accessing justice, and that liberal bail provisions might undermine the protective intent of the legislation. The courts have repeatedly emphasized that the special nature of these offenses requires a departure from the general principles of bail jurisprudence.

Supreme Court’s Analysis and Decision

Inadequate Reasoning by High Court

The Supreme Court’s intervention in this case was prompted by concerns about the quality of judicial reasoning demonstrated by the Patna High Court in granting bail to the accused superintendent. The bench comprising Justices Vikram Nath and Sandeep Mehta found that the High Court’s order dated January 18, 2024, lacked proper reasoning and failed to consider the statutory safeguards provided to victims under the SC/ST Act [7].

The Supreme Court emphasized that when dealing with cases under special legislation like the SC/ST Act, courts must demonstrate heightened sensitivity to the legislative intent and the special protections afforded to vulnerable communities. The failure to provide adequate reasoning in bail orders undermines the rule of law and fails to serve the interests of justice.

Application of “Shock the Conscience” Test

In cancelling the bail, the Supreme Court applied the well-established principle that bail may be cancelled when the facts of the case “shock the conscience” of the court. This legal test, developed through judicial precedent, provides courts with the discretionary power to cancel bail in exceptional circumstances where the gravity of the alleged offenses and their impact on society warrant such intervention [8].

The Court’s reasoning shows how bail cancellation, especially in cases of trafficking involving women inmates, is treated with heightened judicial sensitivity. Trafficking of vulnerable women by someone in a position of trust was seen as a grave violation of human dignity and social order. The Court’s strong language underlined the seriousness of the allegations and their potential to undermine public confidence in protective institutions.

Statutory Compliance and Victim Protection

The Supreme Court’s decision emphasizes the importance of statutory compliance in cases involving vulnerable populations. The Court noted that the High Court had failed to consider the special provisions under the SC/ST Act that are designed to protect victims and ensure that they receive appropriate legal safeguards throughout the judicial process.

This aspect of the decision reinforces the principle that special legislation creates special obligations for courts, requiring them to demonstrate particular sensitivity to the needs and rights of protected classes. The failure to comply with these statutory requirements not only violates the law but also undermines the fundamental purpose of protective legislation.

Human Trafficking Laws and Their Application

Constitutional and Legal Framework

Human trafficking in India is addressed through multiple legal instruments, with the Constitution of India providing the foundational framework through Article 23, which prohibits traffic in human beings and forced labor. This constitutional prohibition is operationalized through various statutes, including the Indian Penal Code provisions on kidnapping and abduction, the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956, and specific provisions in the SC/ST Act addressing trafficking of members of these communities.

The Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act specifically addresses trafficking for the purpose of prostitution and contains provisions for the rescue, rehabilitation, and protection of trafficking victims. The Act recognizes that trafficking often involves vulnerable populations, including women from marginalized communities, and provides for special courts and procedures to address these crimes effectively.

International Obligations and Domestic Implementation

India’s approach to combating human trafficking is also shaped by its international obligations under various treaties and conventions, including the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and its Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children. These international instruments emphasize the need for comprehensive approaches to trafficking that address prevention, prosecution, and protection.

The integration of international standards into domestic law has influenced judicial interpretation of trafficking cases, with courts increasingly recognizing the need for victim-centered approaches that prioritize the rights and dignity of trafficking survivors. This perspective is particularly relevant in cases involving institutional trafficking, where victims may have been repeatedly traumatized by those in positions of authority.

Institutional Accountability and Regulatory Framework

Oversight Mechanisms for Shelter Homes

The operation of shelter homes in India is governed by a complex regulatory framework involving multiple stakeholders, including state governments, district authorities, and various oversight bodies. The Juvenile Justice Act and related rules prescribe detailed requirements for the establishment, operation, and monitoring of such institutions, including provisions for regular inspections, staff qualifications, and resident welfare.

The case highlights critical gaps in the oversight mechanisms that allowed alleged trafficking activities to occur within a government-recognized shelter facility. This raises important questions about the effectiveness of existing monitoring systems and the need for more robust accountability mechanisms to prevent the exploitation of vulnerable residents.

Role of Civil Society and Monitoring

Civil society organizations play a crucial role in monitoring shelter homes and ensuring that residents receive appropriate care and protection. The involvement of NGOs, human rights organizations, and community groups in oversight activities can help identify problems early and provide additional layers of accountability beyond government monitoring systems.

The present case underscores the importance of creating multiple channels for reporting and addressing concerns about institutional care, including mechanisms that allow residents themselves to raise complaints without fear of retaliation. The development of such systems requires collaboration between government agencies, civil society organizations, and legal institutions.

Bail Jurisprudence and Special Legislation

General Principles vs. Special Circumstances

The Supreme Court’s decision in this case illustrates the tension between general principles of bail jurisprudence, which favor the liberty of the accused, and the special considerations that apply in cases involving vulnerable populations and serious offenses. While the general rule is that bail should be granted unless there are compelling reasons to deny it, the decision of bail cancellation in cases involving trafficking of women inmates under special legislation like the SC/ST Act reflects the need for different standards that address specific policy concerns.

This approach recognizes that certain types of crimes, particularly those targeting marginalized communities or involving gross violations of trust, may warrant different treatment in the criminal justice system. The courts must balance the fundamental right to liberty against the need to protect vulnerable populations and maintain public confidence in the justice system.

Precedential Impact and Future Applications

The Supreme Court’s decision in this case is likely to have significant precedential impact on future bail decisions involving trafficking cases under the SC/ST Act. The Court’s emphasis on adequate reasoning, statutory compliance, and victim protection provides clear guidance for lower courts handling similar cases.

The decision of cancellation of bail for women inmates involved in trafficking case underscores that institutional positions of trust carry heightened responsibilities, with broader implications for other cases of abuse of authority. This principle has broader applications beyond trafficking cases and may influence bail decisions in other contexts involving abuse of authority or institutional negligence.

Implications for Women’s Rights and Protection

Gender Dimensions of Institutional Trafficking

The case highlights the particular vulnerabilities faced by women in institutional care settings, where power imbalances and isolation can create conditions conducive to exploitation. Women seeking shelter from domestic violence, trafficking, or other forms of harm often have limited alternatives and may be particularly dependent on the protection offered by institutional care.

The alleged trafficking of women residents by the superintendent represents a profound violation of the fundamental premise of shelter homes as safe spaces for vulnerable women. This breach of trust not only harms the immediate victims but also undermines the credibility of the entire shelter system, potentially deterring other women from seeking necessary protection.

Legal Remedies and Support Systems

The legal framework addressing trafficking of women includes various remedies and support systems designed to address both the immediate needs of victims and the longer-term goal of rehabilitation and reintegration. These include provisions for medical care, psychological support, legal assistance, and economic rehabilitation.

The effectiveness of these support systems depends largely on their implementation at the ground level, including the training and oversight of institutional staff, the availability of resources for victim services, and the coordination between different agencies involved in victim protection and case prosecution.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s ruling on bail cancellation in women inmates trafficking case underscores the importance of statutory compliance and judicial sensitivity in cases affecting vulnerable groups. The Court’s strong language and emphasis on statutory compliance send a clear message about the seriousness with which such cases must be treated by the judicial system [9].

This landmark decision reinforces several important principles: the heightened responsibility of those in positions of institutional trust, the special protections afforded to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes under anti-atrocity legislation, and the need for courts to demonstrate appropriate sensitivity in cases involving the cancellation of bail for women inmates accused of trafficking. The ruling also highlights the importance of adequate judicial reasoning and the proper application of statutory safeguards in bail determinations.

The case serves as a reminder of the ongoing challenges faced in protecting vulnerable women in institutional settings and the critical importance of robust oversight mechanisms, accountability systems, and legal remedies. As India continues to develop its approach to combating trafficking and protecting vulnerable populations, decisions like this one provide important guidance for legal practitioners, policymakers, and institutional administrators working to ensure that protective systems truly serve their intended purpose.

The precedential impact of this decision is likely to be felt across multiple areas of law, from bail jurisprudence to institutional accountability, reinforcing the principle that the protection of vulnerable populations requires not just appropriate legislation but also its rigorous and sensitive implementation by all stakeholders in the justice system.

References

[1] Victim X v. State of Bihar and Another, 2025 LiveLaw (SC) 733. Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/sc-judgments/2025-livelaw-sc-733-x-versus-the-state-of-bihar-and-anr-298317

[2] “‘Savior Turned Devil’: Supreme Court Cancels Bail Of Woman In-Charge Of Bihar Shelter Home,” LiveLaw (July 21, 2025). Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/supreme-court-cancels-bail-of-woman-in-charge-of-bihar-gaighat-shelter-home-accused-of-immoral-trafficking-298316

[3] The Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989.

[4] “SC Cancels Bail of Patna Care Home Superintendent,” Law Trend (July 22, 2025). Available at: https://lawtrend.in/sc-cancels-bail-of-patna-care-home-superintendent-accused-of-exploiting-inmates-terms-allegations-grave-and-reprehensible/

[5] The Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Act, 2018.

[6] “Is the Absence of Prima Facie Offence a Valid Ground for Granting Anticipatory Bail in SC/ST Matters?” Legal Bites. Available at: https://www.legalbites.in/topics/articles/is-the-absence-of-prima-facie-offence-a-valid-ground-for-granting-anticipatory-bail-in-scst-matters-1182764

[7] “Case of Saviour turning into a devil; Supreme Court cancels Superintendent’s bail,” SCC Online (July 24, 2025). Available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/07/24/supreme-court-cancels-superintendents-bail-uttar-raksha-grih-accused-trafficking-women-legal-news/

[8] “Cancellation of Bail When Facts Shock Court’s Conscience,” Supreme Court Observer (July 28, 2025). Available at: https://www.scobserver.in/supreme-court-observer-law-reports-scolr/cancellation-of-bail-when-facts-shock-courts-conscience-victim-x-v-state-of-bihar-cancellation-of-bail/

[9] The Constitution of India. Available at: https://www.india.gov.in/sites/upload_files/npi/files/coi_part_full.pdf

Ensuring Justice for the Marginalized: Supreme Court’s Initiative to Address Delays in Appeals for Indigent Prisoners

Introduction

The Indian judicial system has long grappled with the challenge of ensuring equitable access to justice, particularly for economically disadvantaged individuals within the criminal justice framework. In a significant recent development, the Supreme Court of India has directed High Courts and jail superintendents across the nation to provide comprehensive feedback regarding procedural delays in filing appeals for indigent prisoners [1]. This directive emerges from the Supreme Court’s recognition of systemic barriers that prevent economically weaker sections of society from exercising their fundamental right to appeal criminal convictions.

The initiative represents a crucial step toward addressing the constitutional mandate of equal justice under law, as enshrined in Article 14 of the Indian Constitution, which guarantees equality before the law and equal protection of laws. The Supreme Court’s intervention acknowledges that delays in filing appeals can effectively deny justice to those who cannot afford legal representation, thereby creating a two-tiered justice system based on economic capacity.

The Supreme Court Legal Services Committee’s Framework

The Supreme Court Legal Services Committee (SCLSC) has proposed a detailed framework to the apex court, which subsequently directed High Court Legal Services Committees and jail superintendents to respond to these recommendations [2]. This framework specifically aims to address the systemic delays in filing appeals for indigent prisoners and the procedural hurdles they face when attempting to challenge their criminal convictions.

The SCLSC’s proposals stem from extensive consultation with various stakeholders in the criminal justice system, including legal aid lawyers, prison officials, and judicial officers. The committee identified several critical gaps in the current system that disproportionately affect prisoners who lack financial resources or legal awareness. These gaps often result in appeals being filed beyond statutory limitation periods, effectively barring prisoners from challenging potentially erroneous convictions or excessive sentences.

The framework particularly emphasizes the need for systematic coordination between jail authorities, legal services committees, and the judiciary to ensure that no indigent prisoner is denied the opportunity to appeal due to delays in filing appeals for indigent prisoners or lack of awareness about their legal rights.

Legislative Foundation: The Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987

The legal framework governing free legal aid to indigent persons finds its foundation in the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987. Section 12 of this Act specifically defines categories of persons entitled to legal services, which includes “a person in custody” [3]. The Act establishes a comprehensive network of legal services authorities at national, state, district, and taluk levels to ensure that legal services reach the most marginalized sections of society.

Under Section 12 of the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987, the following categories of persons are entitled to free legal services: “a member of a Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe; a victim of trafficking in human beings or begar as referred to in Article 23 of the Constitution; a woman or a child; a person with disability as defined in clause (i) of section 2 of the Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act, 1995; a person under circumstances of undeserved want such as being a victim of a mass disaster, violence, flood, drought, earthquake or industrial disaster; or a person in custody, including custody in a protective home within the meaning of clause (g) of section 2 of the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956 or in a psychiatric hospital or psychiatric nursing home within the meaning of clause (g) of section 2 of the Mental Health Act, 1987” [4].

The Act further stipulates in Section 12(h) that any person whose annual income does not exceed the prescribed limit is entitled to free legal services. The Supreme Court Legal Services Committee has set this limit at Rs. 5,00,000 annually, recognizing the need to extend legal aid to a broader section of society.

Constitutional Imperatives and Judicial Precedents

The Supreme Court’s directive draws strength from fundamental constitutional principles and established judicial precedents that emphasize the state’s obligation to provide effective legal aid. Article 39A of the Constitution, inserted during the 42nd Amendment, mandates that “the State shall secure that the operation of the legal system promotes justice, on a basis of equal opportunity, and shall, in particular, provide free legal aid, by suitable legislation or schemes or in any other way, to ensure that opportunities for securing justice are not denied to any citizen by reason of economic or other disabilities.”

The landmark judgment in Hussainara Khatoon v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar (1979) established the principle that speedy trial is a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution [5]. The Supreme Court observed that prolonged detention without trial violates the right to life and personal liberty, and the state has a positive obligation to ensure that the poor and illiterate are not denied their constitutional rights due to their economic condition.

In M.H. Hoskot v. State of Maharashtra (1978), the Supreme Court held that free legal aid is a constitutional right of every accused person who is unable to secure legal services on account of reasons such as poverty, indigence or incommunicado situation [6]. The Court emphasized that this right is implicit in Article 21 and is also a mandate under Article 39A.

The principle established in Khatri v. State of Bihar (1981) further reinforced that legal aid must be provided at the earliest stage of criminal proceedings, including during police investigation, and continues through all stages including appeals [7]. This judgment established that the failure to provide legal aid at any stage would vitiate the proceedings.

Current Challenges in the Appeal Process

The Supreme Court’s recent directive addresses several systemic challenges that have emerged in the criminal appeals process, particularly affecting indigent prisoners. Primary among these challenges is the lack of awareness among prisoners about their right to appeal and the procedures involved in filing appeals. Many prisoners, especially those from rural and economically disadvantaged backgrounds, are unaware that they can challenge their convictions or sentences through the appellate process.

Another significant challenge lies in the coordination between jail authorities and legal services committees. Often, prisoners who wish to file appeals face bureaucratic hurdles in accessing legal aid lawyers or in having their applications processed within the statutory limitation periods. The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, under Section 383, provides that an appeal from a conviction by a Court of Session shall be filed within thirty days from the date of the judgment [8].

The time limitation creates particular hardship for indigent prisoners who may take time to understand their legal options or to obtain legal representation. While the appellate courts have powers under Section 5 of the Limitation Act, 1963, to condone delay upon showing sufficient cause, the burden of proving such cause often proves difficult for unrepresented prisoners.

Regulatory Framework for Prison Administration and Legal Aid

The prison administration in India operates under the dual framework of the Prisons Act, 1894, and various state prison manuals that govern the day-to-day functioning of correctional institutions. Under Section 30 of the Prisons Act, prisoners have the right to communicate with legal advisers, and this right extends to accessing legal aid services provided under the Legal Services Authorities Act.

The Supreme Court has, through various judgments, established specific guidelines for prison administration regarding legal aid. In Sunil Batra v. Delhi Administration (1978), the Court laid down detailed guidelines for prison reforms, including provisions for legal aid and the right of prisoners to meet with lawyers [9]. These guidelines emphasize that jail authorities must facilitate, rather than hinder, prisoners’ access to legal services.

The Model Prison Manual 2016, developed by the Bureau of Police Research and Development, incorporates these judicial pronouncements and provides detailed procedures for facilitating legal aid to prisoners. Chapter 8 of the Manual specifically deals with legal aid and requires jail superintendents to maintain records of prisoners entitled to legal aid and to ensure timely communication with legal services authorities.

The Role of High Court Legal Services Committees

High Court Legal Services Committees, established under Section 3A of the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987, play a crucial role in coordinating legal aid services within their respective jurisdictions. These committees are headed by a sitting judge of the High Court and include representatives from the bar, legal academia, and civil society.

The committees are mandated to monitor the functioning of legal services authorities within their jurisdiction and to ensure that legal aid reaches entitled persons effectively. In the context of criminal appeals, these committees coordinate with jail authorities to identify prisoners who require legal assistance and to assign competent lawyers for representing them in appellate proceedings.

The Supreme Court’s directive to High Court Legal Services Committees seeks their input on existing procedures and potential improvements in the system for filing appeals for indigent prisoners. This collaborative approach recognizes that each High Court jurisdiction may face unique challenges based on local conditions, caseload, and available resources.

Jail Superintendents as Gatekeepers of Justice

Jail superintendents occupy a critical position in the criminal justice system as they serve as the primary interface between incarcerated individuals and the outside legal system. Their role extends beyond mere custodial responsibilities to include facilitating prisoners’ access to legal remedies.

Under the existing legal framework, jail superintendents are required to maintain detailed records of prisoners, including information about their legal status, pending cases, and eligibility for legal aid. They must also facilitate communication between prisoners and their legal representatives, including lawyers appointed through legal aid schemes.

The Supreme Court’s directive recognizes that jail superintendents possess firsthand knowledge of the practical challenges faced by indigent prisoners in filing appeals. Their feedback is essential for understanding ground-level implementation issues and for developing realistic solutions that can be effectively implemented across the diverse prison systems in different states.

Procedural Reforms and Best Practices

The Supreme Court’s initiative is expected to result in significant procedural reforms aimed at streamlining the appeal process for indigent prisoners. These reforms may include the establishment of dedicated legal aid cells within prisons, regular legal literacy programs for prisoners, and simplified procedures for filing appeals.

One potential reform involves the creation of a standardized system for identifying prisoners eligible for legal aid and automatically triggering the process of legal representation. This could involve coordination between jail authorities and legal services committees to ensure that all eligible prisoners are informed of their rights within a specified timeframe after conviction.

Another area of potential reform relates to the use of technology in facilitating legal aid delivery. Video conferencing facilities in prisons can enable prisoners to consult with legal aid lawyers without the need for physical visits, thereby reducing delays and improving access to legal services.

Impact on the Criminal Justice System

The Supreme Court’s directive has far-reaching implications for the criminal justice system in India. By addressing delays in filing appeals for indigent prisoners, the initiative promises to reduce the number of cases where appeals become time-barred due to procedural delays rather than lack of merit.

This development aligns with the broader goals of judicial reform in India, which emphasize reducing pendency, improving access to justice, and ensuring that the legal system serves all citizens equitably regardless of their economic status. The initiative also reinforces the principle that the right to appeal is not merely a procedural formality but a substantive component of the right to fair trial.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The Supreme Court’s directive to High Courts and jail superintendents regarding delays in filing appeals for indigent prisoners represents a significant step toward realizing the constitutional promise of equal justice under law. This initiative acknowledges that true access to justice requires not only formal legal rights but also effective mechanisms for exercising those rights.

The success of this initiative will depend on the coordinated efforts of all stakeholders in the criminal justice system, including the judiciary, legal services authorities, prison administration, and the legal profession. It requires a fundamental shift from viewing legal aid as charity to recognizing it as a constitutional entitlement that must be delivered efficiently and effectively.

As the legal system continues to evolve, initiatives like this serve as important reminders that justice delayed is justice denied, and that the measure of a legal system lies not in its complexity or sophistication, but in its ability to serve the most vulnerable members of society. The Supreme Court’s intervention in this matter demonstrates the judiciary’s commitment to addressing systemic issues such as delays in filing appeals for indigent prisoners, ensuring that economic disadvantage does not become a barrier to accessing appellate remedies in criminal cases.

The implementation of recommendations emerging from this directive will likely establish new benchmarks for legal aid delivery in India and may serve as a model for other developing jurisdictions grappling with similar challenges in ensuring equitable access to appellate justice for indigent accused persons.

References

[1] LiveLaw. “Supreme Court Seeks Responses Of HC Legal Services Committees & Jail Superintendents On SCLSC’s Suggestions For Timely Filing Of Appeals.” September 9, 2025. https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/supreme-court-seeks-responses-of-hc-legal-services-committees-jail-superintendents-on-sclscs-suggestions-for-timely-filing-of-appeals-303271

[2] Supreme Court Observer. “Supreme Court grants ₹5 lakhs compensation for delay in prisoner’s release after bail.” June 27, 2025. https://www.scobserver.in/journal/supreme-court-grants-%E2%82%B95-lakhs-compensation-for-delay-in-prisoners-release-after-bail/

[3] The Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987. Section 12. https://nalsa.gov.in/acts-rules/the-legal-services-authorities-act-1987

[4] National Legal Services Authority. “FAQs.” https://nalsa.gov.in/faqs/

[5] Hussainara Khatoon v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar, AIR 1979 SC 1369

[6] M.H. Hoskot v. State of Maharashtra, AIR 1978 SC 1548

[7] Khatri v. State of Bihar, AIR 1981 SC 928

Supreme Court’s Orders on Coal Shortage Cost Sharing in the Power Sector: A Legal Analysis

Introduction

The Indian power sector has witnessed significant judicial interventions in recent years, particularly concerning coal shortage cost sharing. The Supreme Court of India’s recent ruling in September 2025 has established crucial precedents for how distribution companies (DISCOMs) must handle the financial burden of coal shortages and associated costs [1]. This landmark judgment has far-reaching implications for the power sector’s operational framework and regulatory compliance mechanisms.

The power sector in India operates under a complex regulatory framework where multiple stakeholders, including power generation companies, distribution companies, and regulatory authorities, must navigate intricate legal and operational challenges. Coal shortage cost sharing has become a recurring issue, creating disputes over cost allocation and responsibility sharing among various entities in the power supply chain.

Regulatory Framework Governing Coal Shortage Cost Allocation

The Electricity Act, 2003: Foundation of Power Sector Regulation

The Electricity Act, 2003, serves as the primary legislation governing India’s electricity sector, providing the legal framework for regulation, generation, transmission, and distribution of electrical energy [2]. Section 125 of the Electricity Act, 2003, specifically addresses appeals to the Supreme Court, stating that appeals can only be made on “substantial questions of law.” This provision has been crucial in determining the scope of judicial review in power sector disputes.

The Act establishes a three-tier regulatory structure comprising the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC), State Electricity Regulatory Commissions (SERCs), and the Appellate Tribunal for Electricity (APTEL). This hierarchical framework ensures proper adjudication of disputes while maintaining regulatory consistency across the sector.

Role of Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC)

CERC operates as the apex regulatory authority for the electricity sector, with jurisdiction over inter-state transmission, bulk power markets, and central generating companies [3]. Under the Electricity Act, 2003, CERC possesses the authority to determine tariffs for generating companies and transmission licensees, regulate inter-state transmission and trading of electricity, and adjudicate disputes between licensees.

In matters relating to coal shortage compensation, CERC has consistently applied the principle of pro-rata apportionment among all beneficiaries. This approach ensures that costs arising from external factors such as coal shortages are distributed fairly among all power purchasers, preventing any single entity from bearing disproportionate financial burdens.

Appellate Tribunal for Electricity (APTEL) Jurisdiction

APTEL functions as the appellate authority for decisions made by CERC and SERCs, providing an intermediate judicial forum before appeals can be made to the Supreme Court [4]. The tribunal has jurisdiction to hear appeals against orders of electricity regulatory commissions and can also adjudicate disputes involving generating companies, transmission licensees, and distribution licensees.

The tribunal’s role in coal shortage cost allocation cases has been to ensure that regulatory decisions align with the broader objectives of the Electricity Act, 2003, while maintaining sectoral stability and protecting consumer interests. APTEL’s decisions have consistently supported the principle of equitable cost sharing among all power purchasers.

The GMR Kamalanga Case: A Landmark Supreme Court Ruling

Case Background and Factual Matrix

The Supreme Court’s decision in Haryana Power Purchase Centre (HPPC) and Others v. GMR Kamalanga Energy Limited and Others represents a significant milestone in power sector jurisprudence [5]. The dispute originated from a coal shortfall at GMR Kamalanga Energy Limited’s (GKEL) 1050 MW thermal power plant in Odisha, which forced the company to rely on expensive imported coal to meet its supply obligations.

The central question before the court was whether additional costs arising from coal shortages should be shared proportionally among all power procurers or borne exclusively by the affected distribution companies. This dispute involved multiple parties, including Haryana Utilities, which claimed exclusive rights to 300 MW linkage coal under their Power Purchase Agreement (PPA), and GRIDCO of Odisha, which asserted priority rights based on their earlier agreement.

Legal Arguments and Contentions

Haryana Utilities argued that their PPA specifically allocated 300 MW of linkage coal exclusively for their use, thereby exempting them from sharing the additional costs incurred due to coal shortages affecting other beneficiaries. They contended that the contractual arrangement created distinct entitlements that should be respected in cost allocation decisions.

GRIDCO of Odisha, on the other hand, claimed priority rights under their earlier agreement, arguing that temporal precedence should determine allocation priorities during coal shortage scenarios. Both parties sought to establish preferential treatment in cost allocation, challenging CERC’s order for proportional cost sharing among all beneficiaries.

Supreme Court’s Analysis and Decision

Chief Justice B.R. Gavai and Justice K. Vinod Chandran, constituting the bench, delivered a unanimous judgment that upheld the concurrent findings of CERC and APTEL [6]. The court established several important legal principles that will guide future coal shortage cost allocation disputes.

The Supreme Court categorically rejected the argument that any distribution company could claim priority for power supply based on the prior date of agreement or specific coal source allocations. The court observed that “coal supply from all sources has to be apportioned amongst all the three DISCOMs in proportion to the energy supplied to them.”

The judgment emphasized that appeals under Section 125 of the Electricity Act can only be entertained on substantial questions of law. The court noted that “unless it is found that the findings are perverse, arbitrary or in violation of statutory provisions, it will not be permissible for this Court to interfere with the same.”

Change in Law Provisions and Their Application

Understanding Change in Law Events

Change in Law provisions in power purchase agreements serve as risk allocation mechanisms that protect generating companies from unforeseen regulatory or legal changes that materially affect project economics [7]. These provisions typically allow generators to seek compensation for additional costs or reduced revenues resulting from changes in applicable laws, regulations, or government policies.

In the context of coal shortage scenarios, Change in Law events can be triggered when government policies or regulatory decisions force generators to alter their fuel procurement strategies, leading to increased operational costs. The application of these provisions requires careful analysis of causation, materiality, and the scope of compensable events.

Regulatory Treatment of Change in Law Claims

CERC has developed detailed guidelines for evaluating Change in Law claims, requiring generators to demonstrate direct causation between the legal/regulatory change and the claimed impact. The commission’s approach emphasizes the need for comprehensive documentation and quantitative analysis to support compensation claims.

The regulatory framework mandates that Change in Law compensation should be allocated among all beneficiaries in proportion to their contracted capacity or energy offtake. This approach ensures that the financial burden is distributed equitably, preventing any single purchaser from bearing disproportionate costs.

Cost Sharing Mechanisms in Power Purchase Agreements

Proportional Cost Sharing Principles

The principle of proportional cost sharing has emerged as the dominant framework for allocating unforeseen costs in the power sector. This approach distributes additional costs among all beneficiaries based on their contracted capacity or actual energy offtake, ensuring equitable treatment regardless of specific contractual provisions or temporal precedence.

Proportional allocation mechanisms serve multiple policy objectives, including maintaining sector stability, preventing cross-subsidization among different consumer categories, and ensuring that cost recovery remains aligned with benefit distribution. These principles have been consistently applied by regulatory authorities across various dispute scenarios.

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

The implementation of proportional cost sharing mechanisms faces several practical challenges, including accurate measurement of beneficiary shares, timing of cost recovery, and handling of disputes over allocation methodologies. Regulatory authorities have addressed these challenges through detailed procedural guidelines and standardized calculation methodologies.

CERC has issued specific regulations governing cost allocation procedures, requiring detailed documentation of costs, transparent calculation methodologies, and periodic reconciliation mechanisms. These measures ensure that cost sharing arrangements remain fair and administratively feasible.

Impact on Distribution Companies and Power Market Dynamics

Financial Implications for DISCOMs

The Supreme Court’s ruling on proportional cost sharing has significant financial implications for distribution companies across India. DISCOMs can no longer claim exemptions from sharing coal shortage costs based on specific contractual arrangements or temporal precedence, potentially increasing their financial exposure during coal shortage scenarios.

This judicial precedent requires DISCOMs to incorporate coal shortage risk provisions in their financial planning and tariff calculations [8]. Distribution companies must now account for potential cost sharing obligations when evaluating power purchase agreements and planning their procurement strategies.

Market Efficiency and Risk Distribution

The court’s decision promotes market efficiency by ensuring that risks associated with coal shortages are distributed among all market participants rather than concentrated on specific entities. This approach prevents market distortions that could arise from asymmetric risk allocation and encourages more balanced contractual arrangements.

The ruling also enhances predictability in cost allocation disputes, providing clear guidance to market participants on how coal shortage costs will be distributed. This predictability reduces transaction costs and facilitates more informed decision-making by power sector stakeholders.

Comparative Analysis with International Practices

Global Approaches to Fuel Shortage Cost Allocation

International power markets have developed various approaches to handle fuel shortage cost allocation, ranging from market-based mechanisms to regulatory cost recovery frameworks. European electricity markets typically rely on market mechanisms where generators bear fuel price risks, while regulated markets in developing countries often incorporate cost pass-through provisions similar to India’s approach.

The Indian model of proportional cost sharing aligns with international best practices that emphasize equitable risk distribution among market participants. However, the specific implementation details and regulatory oversight mechanisms reflect India’s unique market structure and developmental priorities.

Lessons from International Dispute Resolution

International experience suggests that clear regulatory guidelines and consistent judicial interpretation are crucial for effective dispute resolution in power sectors. The Supreme Court’s ruling provides such clarity for the Indian context, establishing precedents that align with global trends toward transparent and equitable cost allocation mechanisms.

Future Implications and Sector Development

Evolution of Regulatory Framework

The Supreme Court’s decision is likely to influence the evolution of India’s power sector regulatory framework, potentially leading to more detailed guidelines on coal shortage cost sharing mechanisms and risk distribution principles. Regulatory authorities may need to update their regulations to reflect the judicial interpretation and ensure consistent application across different scenarios.

Future regulatory developments may also address emerging challenges such as renewable energy integration, energy storage costs, and grid modernization expenses, applying similar proportional allocation principles established in the context of coal shortage cost sharing.

Impact on Power Purchase Agreement Design

The ruling will significantly impact how future power purchase agreements are structured, particularly regarding risk allocation clauses and cost sharing mechanisms. Developers and purchasers will need to carefully consider the implications of proportional cost sharing when negotiating contract terms and pricing structures [9].

Legal practitioners and industry participants must now account for the Supreme Court’s interpretation when drafting Change in Law provisions and cost allocation clauses, ensuring alignment with established judicial precedents while protecting their clients’ interests.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s ruling on coal shortage cost sharing represents a watershed moment in Indian power sector regulation, establishing clear principles for equitable cost allocation among market participants. The decision reinforces the regulatory framework’s emphasis on fair treatment and prevents any single entity from claiming preferential treatment based on contractual specifics or temporal precedence.

The judgment’s impact extends beyond the immediate parties, providing guidance for future disputes and influencing how power sector risks are allocated and managed. As India continues to develop its electricity markets and integrate renewable energy sources, these principles will serve as foundational elements for maintaining sector stability and promoting efficient market operations.

The ruling also demonstrates the importance of consistent regulatory interpretation and judicial review in maintaining confidence in India’s power sector regulatory framework. By upholding the decisions of CERC and APTEL, the Supreme Court has reinforced the credibility of sectoral regulators while establishing important precedents for future cost allocation disputes.

References

[1] Supreme Court of India. (2025). Haryana Power Purchase Centre (HPPC) and Others v. GMR Kamalanga Energy Limited and Others. 2025 LiveLaw (SC) 877. Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/pdf_upload/622920202025-09-08-619491.pdf

[2] Government of India. (2003). The Electricity Act, 2003. Act No. 36 of 2003.

[3] Central Electricity Regulatory Commission. (2024). CERC Functions and Jurisdiction.

[4] Appellate Tribunal for Electricity. (2024). Jurisdiction and Powers of APTEL.

[5] LiveLaw. (2025). “Supreme Court Dismisses Discom Appeals, Affirms All Purchasers Must Share Coal Shortage Costs Equally.” Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/supreme-court/electricity-act-supreme-court-dismisses-discom-appeals-affirms-all-purchasers-must-share-coal-shortage-costs-equally-303266

[6] SCC Online. (2025). “DISCOMs must share coal shortage costs equally, cannot claim priority for power supply.” Available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/09/10/supreme-court-discoms-coal-shortage-cost-sharing/

[7] Central Electricity Regulatory Commission. (2019). Guidelines for Determination of Tariff by Competitive Bidding Process for Procurement of Power from Grid Connected Solar PV Power Projects.

[8] Law Chakra. (2025). “Supreme Court Orders States To Settle Electricity Dues Within 4 Years.” Available at: https://lawchakra.in/supreme-court/settle-electricity-dues-in-4years/

[9] Global Legal Insights. (2024). “Energy Laws and Regulations 2025 | India.” Available at: https://www.globallegalinsights.com/practice-areas/energy-laws-and-regulations/india/

Supreme Court on Matrimonial FIR Quashing: Navneesh Aggarwal Case on Section 498A Misuse & Post-Divorce Criminal Proceedings

Introduction

The Supreme Court on matrimonial FIR quashing in Navneesh Aggarwal v. State of Haryana [1] has emerged as a landmark decision that addresses the delicate balance between protecting genuine victims of matrimonial cruelty and preventing the abuse of criminal justice machinery in post-divorce scenarios. This pivotal ruling underscores the Court’s commitment to ensuring that the criminal justice system is not weaponized to perpetuate bitterness and harassment between estranged spouses who have already moved on with their lives.

The judgment represents a significant judicial intervention in matrimonial jurisprudence, particularly concerning the quashing of FIRs registered under Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code and related provisions. By invoking its extraordinary powers under Article 142 of the Constitution, the Supreme Court has established important precedents for determining when criminal proceedings arising from matrimonial disputes should be terminated to serve the broader interests of justice and judicial efficiency.

This decision comes at a time when Indian courts are grappling with an unprecedented number of matrimonial disputes, many of which involve cross-allegations and counter-cases that continue long after the actual marriage has ended. The Supreme Court on Matrimonial FIR Quashing in this case provides crucial guidance on how to distinguish between genuine cases requiring criminal prosecution and those that represent misuse of legal processes for ulterior motives.

Factual Matrix and Background

The case originated from a marriage solemnized in 2018 between the appellant husband and respondent wife, which quickly deteriorated due to irreconcilable differences. Within approximately ten months of the marriage, the respondent wife left the matrimonial home along with her daughter from a previous marriage, setting in motion a series of legal proceedings that would eventually reach the Supreme Court.

The matrimonial breakdown led to multiple cases being filed by both parties, creating a complex web of litigation that is unfortunately common in contemporary Indian matrimonial disputes. Among these proceedings was an FIR registered by the respondent wife against the appellant husband and his family members under Sections 323 (voluntarily causing hurt), 406 (criminal breach of trust), 498A (cruelty by husband or his relatives), and 506 (criminal intimidation) of the Indian Penal Code [2].

Following the grant of divorce, the appellant husband approached the Punjab and Haryana High Court under Section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, seeking quashing of the FIR and related criminal proceedings. However, the High Court dismissed the application, primarily on the grounds that certain allegations regarding victimization of the child had been sufficiently substantiated to warrant continuation of the criminal proceedings.

The High Court’s refusal to quash the proceedings led the appellant to approach the Supreme Court, arguing that the continuation of criminal cases after the finalization of divorce and mutual settlement served no legitimate purpose except to harass and burden the criminal justice system with disputes that were no longer live or relevant.

Legal Framework: Section 482 CrPC and Inherent Powers

Section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, forms the cornerstone of the High Courts’ inherent jurisdiction to quash criminal proceedings. This provision states that “nothing in this Code shall be deemed to limit or affect the inherent power of the High Court to make such orders as may be necessary to give effect to any order under this Code, or to prevent abuse of the process of any Court or otherwise to secure the ends of justice” [3].

The inherent powers under Section 482 are of wide amplitude and are designed to achieve two primary objectives: preventing abuse of the process of law and securing the ends of justice. These powers are not governed by rigid rules but are instead meant to be exercised based on the facts and circumstances of each case, with courts maintaining flexibility to address situations not specifically covered by the procedural code.

In matrimonial contexts, the application of Section 482 has evolved through judicial interpretation to recognize that continuation of criminal proceedings after resolution of matrimonial disputes may sometimes serve no legitimate purpose. Courts have consistently held that where parties have settled their differences and moved on with their lives, the continuation of criminal cases arising from past matrimonial discord may constitute abuse of the legal process.

The Supreme Court has previously established several parameters for exercising inherent powers in matrimonial disputes, including consideration of the nature of allegations, the conduct of parties post-separation, the likelihood of conviction, and the broader interests of justice. The Navneesh Aggarwal case builds upon this jurisprudential foundation while providing fresh insights into the application of these principles.

Analysis of Section 498A: Scope and Misuse

Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code, introduced in 1983, represents a significant legislative intervention designed to address the serious problem of cruelty against women in matrimonial relationships. The provision defines the offense of cruelty by husband or his relatives and prescribes punishment of imprisonment up to three years and fine. The section covers both physical and mental cruelty, including harassment for dowry demands.

While Section 498A was enacted with the laudable objective of protecting women from domestic violence and matrimonial cruelty, its implementation has revealed both strengths and challenges. The provision has undoubtedly served as an important deterrent against domestic violence and has empowered women to seek legal recourse against abusive husbands and in-laws. However, concerns have also been raised about its potential misuse in cases where it is invoked not to seek justice for genuine grievances but as a tool for harassment or negotiation in matrimonial disputes.

The Supreme Court has previously acknowledged the dual nature of Section 498A cases, recognizing that while genuine cases must be prosecuted vigorously, the legal system must also guard against false or exaggerated complaints that can cause serious harm to innocent family members. The Court has emphasized the need for careful evaluation of each case to distinguish between genuine complaints and those filed with ulterior motives.

In the context of post-divorce scenarios, the continued prosecution under Section 498A raises additional complexities. When a marriage has ended and parties have resolved their differences through divorce proceedings, the continuation of criminal cases based on past matrimonial conduct may sometimes serve no constructive purpose and may instead perpetuate animosity and legal harassment.

Supreme Court’s Reasoning and Judicial Approach

The Supreme Court’s decision in Navneesh Aggarwal demonstrates a nuanced understanding of the complexities involved in post-divorce criminal proceedings. The two-judge bench comprising Justice B.V. Nagarathna and Justice K.V. Viswanathan adopted a holistic approach that balanced multiple considerations including the finality of divorce, the settlement between parties, and the broader interests of judicial efficiency and fairness.

The Court’s primary reasoning centered on the principle that once a marital relationship has ended through divorce and parties have moved on with their individual lives, the continuation of criminal proceedings against family members, especially in the absence of specific and proximate allegations, serves no legitimate purpose. The Court observed that such continuation only prolongs bitterness and burdens the criminal justice system with disputes that are no longer live or relevant [4].

The judgment reflects the Court’s recognition that the criminal justice system should not become a vehicle for perpetuating post-divorce animosity. The Court emphasized that in appropriate cases, the power to quash criminal proceedings is essential to uphold fairness and bring closure to personal disputes that have run their course. This approach demonstrates judicial wisdom in recognizing that legal processes must serve constructive purposes rather than becoming instruments of ongoing harassment.

The Court also noted the significance of the fact that both parties had accepted the finality of the divorce decree and had entered into a comprehensive settlement that resolved all their differences. The existence of such a settlement, coupled with the withdrawal of other pending cases between the parties, indicated that the criminal proceedings were no longer serving any legitimate purpose.

Application of Article 142: Extraordinary Constitutional Powers

The Supreme Court’s invocation of Article 142 of the Constitution in this case represents a significant aspect of the judgment that deserves detailed analysis. Article 142 confers upon the Supreme Court the power to pass any decree or make any order necessary for doing complete justice in any cause or matter pending before it. This power is extraordinary in nature and is typically exercised in exceptional circumstances where ordinary legal remedies prove inadequate.

The Court’s decision to exercise Article 142 powers in Navneesh Aggarwal reflects its understanding that complete justice required not just the mechanical application of procedural rules but a comprehensive evaluation of the overall situation facing the parties. The Court recognized that the continuation of criminal proceedings in the specific circumstances of the case would result in injustice rather than serving the cause of justice.

The application of Article 142 in matrimonial contexts has evolved through various Supreme Court decisions, with the Court consistently emphasizing that these powers should be exercised judiciously and only when necessary to achieve complete justice. In matrimonial disputes, the Court has used these powers to quash proceedings, direct settlements, and provide relief that may not be available through ordinary legal processes.

The Navneesh Aggarwal judgment adds to this jurisprudential development by establishing that Article 142 powers can appropriately be used to quash post-divorce criminal proceedings where such proceedings serve no legitimate purpose and instead constitute harassment of the parties involved.

Balancing Victim Rights and Abuse Prevention

One of the most challenging aspects of matrimonial jurisprudence involves striking the right balance between protecting genuine victims of domestic violence and preventing abuse of legal processes by parties with ulterior motives. The Navneesh Aggarwal case illustrates how courts must navigate this delicate balance while ensuring that justice is served in both directions.

The Supreme Court’s approach in this case demonstrates sensitivity to the rights of genuine victims while simultaneously recognizing the need to prevent harassment through frivolous or vexatious criminal proceedings. The Court’s analysis focused on several key factors that help distinguish between genuine cases requiring prosecution and those that may represent misuse of legal processes.

First, the Court examined the timing of the criminal complaint relative to the divorce proceedings and settlement. The fact that parties had comprehensively settled their differences and moved on with their lives was given significant weight in determining that continued prosecution served no legitimate purpose. Second, the Court considered the specific nature of allegations and the availability of corroborating evidence to support the charges.

The judgment also reflects the Court’s understanding that the criminal justice system’s resources are finite and should be directed toward cases that genuinely require prosecution rather than being consumed by disputes that have essentially been resolved through other means. This approach serves both the interests of individual justice and broader judicial efficiency.

Impact on Criminal Justice Administration

The Supreme Court’s decision in Navneesh Aggarwal has significant implications for the administration of criminal justice in matrimonial contexts. By establishing clear parameters for when post-divorce criminal proceedings should be quashed, the judgment provides valuable guidance to lower courts dealing with similar situations.

The decision contributes to judicial efficiency by reducing the burden on criminal courts that are already overburdened with pending cases. When criminal proceedings arise from matrimonial disputes that have been comprehensively resolved through divorce and settlement, their continuation often represents an inefficient use of judicial resources that could be better deployed in addressing genuine criminal matters.

The judgment also has implications for the conduct of matrimonial litigation more broadly. By signaling that criminal complaints filed primarily for harassment or negotiation purposes may be quashed when circumstances warrant, the Court provides a deterrent against the misuse of criminal law in matrimonial contexts.

From a systemic perspective, the decision encourages parties to matrimonial disputes to seek comprehensive resolution of their differences rather than allowing criminal proceedings to linger indefinitely. This approach promotes finality in matrimonial disputes and helps prevent the perpetuation of conflicts through multiple legal forums.

Precedential Value and Future Applications

The Navneesh Aggarwal judgment establishes important precedents that will guide future decisions involving post-divorce criminal proceedings. The Court’s analysis provides a framework for evaluating when criminal proceedings arising from matrimonial disputes should be permitted to continue and when they should be quashed in the interests of justice.

The precedential value of the supreme court on matrimonial FIR quashing decision lies particularly in its establishment of factors that courts should consider when evaluating applications for quashing matrimonial FIRs. These factors include the finality of divorce proceedings, the existence of comprehensive settlements between parties, the specific nature of criminal allegations, and the broader question of whether continued prosecution serves any legitimate purpose.

The judgment also establishes the principle that courts should be vigilant against allowing the criminal justice system to become a tool for post-divorce harassment. This principle has broad applications beyond the specific facts of the Navneesh Aggarwal case and can guide judicial decision-making in various matrimonial contexts.

Future applications of this precedent are likely to focus on the specific factual circumstances of each case, with courts examining whether the continuation of criminal proceedings serves legitimate purposes or merely perpetuates disputes that have been otherwise resolved.

Challenges in Implementation

While the Supreme Court’s decision provides valuable guidance, its implementation at the trial court and high court levels may face several practical challenges. One significant challenge involves the determination of when parties have truly “moved on” with their lives and when criminal proceedings have become purely vexatious rather than serving legitimate purposes.

Trial courts and high courts will need to develop appropriate mechanisms for evaluating the genuineness of settlements and the completeness of dispute resolution in matrimonial contexts. This evaluation requires careful examination of the circumstances surrounding divorce proceedings, the nature of any settlements reached, and the conduct of parties both during and after matrimonial litigation.

Another challenge involves ensuring that the precedent established in Navneesh Aggarwal is not misused by parties seeking to escape legitimate criminal prosecution. Courts will need to maintain vigilance against attempts to characterize genuine criminal cases as mere matrimonial disputes that should be quashed following divorce.

The implementation of the judgment also requires careful attention to the rights of victims who may have legitimate grievances that extend beyond the matrimonial relationship itself. Courts must ensure that the principle of quashing post-divorce proceedings is applied appropriately without prejudicing the rights of genuine victims of criminal conduct.

Comparative Analysis with Related Jurisprudence

The Supreme Court’s approach in Navneesh Aggarwal can be understood in the context of broader jurisprudential developments concerning matrimonial disputes and criminal proceedings. The Court has consistently evolved its approach to these issues, recognizing the need to balance competing interests while ensuring that legal processes serve constructive purposes.

Previous Supreme Court decisions have established various principles governing the quashing of matrimonial FIR, including the importance of genuine settlements, the role of compromise in non-compoundable offenses, and the application of inherent powers to prevent abuse of legal processes. The Navneesh Aggarwal judgment builds upon this foundation while providing additional clarity on the specific context of post-divorce proceedings.

The decision also reflects broader trends in Indian matrimonial jurisprudence toward recognizing the finality of divorce and the importance of allowing parties to move forward with their lives without being encumbered by lingering legal disputes. This approach aligns with contemporary understandings of family law that emphasize resolution and closure rather than perpetual litigation.

International comparative analysis reveals similar approaches in other common law jurisdictions, where courts have recognized the importance of preventing the misuse of criminal law in domestic contexts while maintaining protection for genuine victims of domestic violence.

Policy Implications and Recommendations