Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

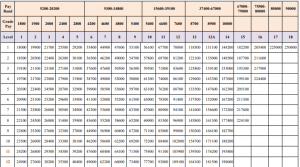

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

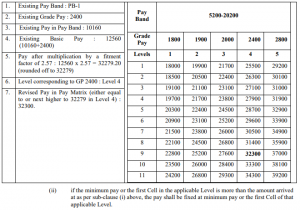

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

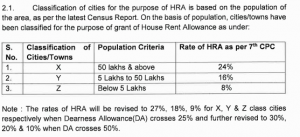

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

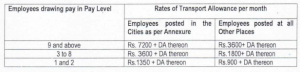

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Oil and Gas Land Rights: PNGRB Act, Pipeline ROW, and Exploration Licenses

Introduction

India’s oil and gas sector operates within a complex legal framework that balances federal regulatory authority with state land rights, creating a multifaceted system of land acquisition, pipeline development, and exploration licensing. The sector’s legal architecture encompasses three primary components: the Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board Act, 2006 (PNGRB Act) [1], the Petroleum and Minerals Pipelines (Acquisition of Right of User in Land) Act, 1962 [2], and the comprehensive exploration licensing regime under the Oilfields (Regulation and Development) Act, 1948 [3]. This framework demonstrates the intricate balance between Union regulatory powers and state land rights, particularly in light of recent Supreme Court jurisprudence on mineral taxation and land rights.

Constitutional Framework and Federal Structure

The constitutional division of powers between the Union and states forms the bedrock of oil and gas land rights in India. Article 246 of the Constitution places petroleum regulation under the Union List, specifically Entry 53 (regulation and development of oil fields and mineral oil resources) and Entry 54 (regulation of mines and mineral development) [4]. However, land acquisition, being a state subject under Entry 18 of the State List, creates a jurisdictional interface that requires careful legal navigation.

The recent Supreme Court judgment in Mineral Area Development Authority v. Steel Authority of India (2024) has significantly clarified the taxation landscape for mineral-bearing lands, holding by an 8:1 majority that states retain the power to tax mineral rights under Entry 50 of the State List, subject only to express limitations imposed by Parliament [5]. This decision, while primarily concerning mining, has potential implications for petroleum exploration and production activities, particularly regarding land taxation and revenue sharing.

PNGRB Act Framework and Pipeline Authorization

Regulatory Authority and Scope

The PNGRB Act, 2006, establishes a comprehensive regulatory framework for the midstream and downstream petroleum sector, excluding crude oil and natural gas production. Section 1(4) specifically delineates the Act’s application to “refining, processing, storage, transportation, distribution, marketing and sale of petroleum, petroleum products and natural gas excluding production of crude oil and natural gas” [6].

The PNGRB Act creates a specialized regulatory body with wide-ranging powers under Section 11, including authorization of entities to “lay, build, operate or expand a common carrier or contract carrier” and “lay, build, operate or expand city or local natural gas distribution network” [7]. This regulatory framework operates parallel to land acquisition requirements, creating a dual authorization system where PNGRB approval does not automatically confer land rights.

Pipeline Classification and Land Rights Interface

The PNGRB Act establishes a sophisticated classification system for pipelines, distinguishing between common carriers, contract carriers, and dedicated pipelines. Section 2(j) defines common carriers as “pipelines for transportation of petroleum, petroleum products and natural gas by more than one entity” on a “non-discriminatory open access basis” [8]. This classification system has significant implications for land acquisition, as different pipeline categories may require different approaches to obtaining land rights.

Recent litigation in IMC Limited v. Union of India has highlighted jurisdictional disputes regarding captive pipelines, with the Bombay High Court examining whether the Board has authority to regulate pipelines developed for self-use by entities [9]. This ongoing jurisprudential development affects the interplay between regulatory authorization and land acquisition for petroleum infrastructure.

Authorization Process and Land Acquisition Interface

Section 17 of the PNGRB Act mandates that entities seeking to lay, build, operate or expand pipelines must apply in writing to the Board for authorization. However, Section 19 clarifies that PNGRB authorization does not automatically provide land acquisition rights, stating that entities must separately “furnish the particulars of such activities to the Board within six months from the appointed day” [10].

Section 20 of the PNGRB Act provides for declaring existing pipelines as common or contract carriers, potentially affecting existing land rights and creating new obligations for landowners. While the provision does not itself grant land acquisition powers, it requires careful consideration of property rights and coordination with compensation mechanisms under the land acquisition framework.

Pipeline Rights of Way: The 1962 Act Framework

Legislative Architecture and Scope

The Petroleum and Minerals Pipelines (Acquisition of Right of User in Land) Act, 1962, provides the primary legal mechanism for acquiring land rights for pipeline development. The Act’s preamble establishes its purpose “to provide for the acquisition of right of user in land for laying pipelines for the transport of petroleum and minerals” [11].

Section 3 of the Act empowers the Central Government to acquire rights of user in land where it appears “necessary in the public interest to lay pipelines under such land for the transport of petroleum from one locality to another” [12]. This power extends to both onshore and offshore areas within India’s territorial jurisdiction.

Acquisition Process and Compensation Framework

The acquisition process under the 1962 Act follows a structured approach outlined in Sections 4-9. Section 4 grants extensive survey and investigation powers, allowing authorized persons to “enter upon and survey any land” and “dig or bore into the sub-soil” for determining pipeline feasibility [13].

Section 10 establishes a comprehensive compensation framework, requiring payment for “any damage, loss or injury sustained by any person interested in the land under which the pipeline is proposed to be, or is being, or has been laid” [14]. The compensation determination process involves a two-tier system: initial determination by a competent authority under Section 10(1), with appeal rights to the District Judge under Section 10(2).

The compensation criteria under Section 10(3) specifically address: removal of trees or standing crops, temporary severance of land, and injury to other property or earnings. However, the Act excludes compensation for structures or improvements made after the notification date, ensuring that landowners cannot enhance compensation through post-notification developments [15].

Interface with Environmental and Forest Clearances

Pipeline development under the 1962 Act requires coordination with environmental and forest clearance requirements. The Environmental Impact Assessment Notification, 2006, mandates environmental clearances for pipeline projects exceeding specified thresholds. Forest clearances under the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, are required for pipeline routes passing through forest areas.

The Supreme Court’s judgment in T.N. Godavarman Thirumulpad v. Union of India has established strict guidelines for forest clearances, requiring prior approval from the Central Government for any non-forest use of forest land [16]. These requirements create additional layers of approval beyond the basic land acquisition process under the 1962 Act.

Exploration Licensing and Land Rights

Historical Evolution and Current Framework

India’s petroleum exploration licensing has evolved through several phases, from the nomination regime of the 1970s to the current Hydrocarbon Exploration and Licensing Policy (HELP) introduced in 2016. The Oilfields (Regulation and Development) Act, 1948, provides the foundational legal framework, empowering the Central Government to grant Petroleum Exploration Licenses (PEL) and Petroleum Mining Leases (PML) [17].

The Petroleum and Natural Gas Rules, 1959, enacted under the 1948 Act, provide detailed procedures for licensing. Rule 6 prohibits “prospecting or mining of petroleum except in pursuance of a licence or lease granted under these rules” [18]. The recent amendment in July 2018 expanded the definition of ‘petroleum’ to include shale and other unconventional hydrocarbons, broadening the regulatory scope.

Exploration License Framework and Land Access Rights

Under the current HELP framework, exploration licenses are granted through a competitive bidding process for blocks identified by the government. However, the Supreme Court’s decision in Threesiamma Jacob v. Geologist, Department of Mining and Geology (2013) has clarified that “ownership of sub-soil or mineral wealth should normally follow the ownership of the land, unless the owner of the land is deprived of the same by some valid process” [19].

This judicial pronouncement significantly impacts exploration licensing by recognizing private ownership rights in mineral resources, subject to valid governmental acquisition. The decision creates a framework where exploration companies must either negotiate private agreements with landowners or rely on governmental acquisition processes.

Production Sharing Contracts and Revenue Allocation

The exploration licensing framework operates through Production Sharing Contracts (PSCs) between the government and contractors. Under the model PSC framework, contractors bear exploration costs and risks while sharing production with the government according to predetermined formulas. The Revenue Sharing Model under HELP replaced the earlier profit-sharing mechanism, providing contractors with greater flexibility in cost recovery [20].

Section 6A of the Oilfields (Regulation and Development) Act, 1948, empowers the Central Government to levy royalty on petroleum production. The rate determination follows the Second Schedule of the Petroleum and Natural Gas Rules, 1959, with different rates for onshore and offshore production. Recent litigation in Udaipur Chamber of Commerce v. Union of India addresses whether Goods and Services Tax can be levied on petroleum royalties, with potential implications for overall tax treatment [21].

Judicial Interpretation and Case Law Development

Supreme Court Jurisprudence on Mineral Rights

The Supreme Court’s recent pronouncement in Mineral Area Development Authority v. Steel Authority of India has significant implications for petroleum exploration and production. The Court’s holding that states retain taxation powers over mineral rights, subject only to express Parliamentary limitations, potentially extends to petroleum-bearing lands, reinforcing the legal framework protecting oil and gas land rights. Justice B.V. Nagarathna’s dissenting opinion warned of potential “race to the bottom” scenarios in mineral taxation, which could affect petroleum sector investments [22].

The majority opinion’s distinction between royalty and tax – holding that “royalty is conceptually different from tax” and represents “contractual consideration paid by the mining lessee to the lessor” – provides clarity for petroleum sector revenue arrangements [23]. This distinction affects how petroleum companies structure their agreements with landowners and government entities.

Land Acquisition and Compensation Jurisprudence

The Supreme Court’s interpretation of compensation principles in various land acquisition cases affects petroleum infrastructure development. In State of Rajasthan v. Sharwan Kumar Kumawat, the Court emphasized that “there is neither a right nor it gets vested through an application made over a Government land” [24]. This principle applies to petroleum exploration license applications, confirming that applications do not create vested rights.

The Court’s approach to determining “public purpose” in land acquisition cases, particularly in the context of private company projects, affects petroleum infrastructure development. The requirement for demonstrating genuine public benefit rather than private commercial advantage influences how petroleum companies approach land acquisition for pipeline and infrastructure projects.

Contemporary Challenges and Regulatory Interface

Environmental Compliance and Land Use Integration

The intersection of petroleum exploration licensing with environmental regulations creates complex compliance requirements. The National Green Tribunal’s jurisdiction under the National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, extends to petroleum exploration and production activities affecting environmental quality. Recent NGT decisions have emphasized the need for comprehensive environmental impact assessments before granting exploration permissions, highlighting the importance of safeguarding oil and gas land rights during project planning.

The Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, and the Coastal Regulation Zone Notification further restrict exploration activities in ecologically sensitive areas. These restrictions require petroleum companies to demonstrate minimal environmental impact and often necessitate alternative route planning for pipeline projects.

State Government Interface and Dual Approval Requirements

The federal structure necessitates coordination between Union licensing authorities and state land acquisition agencies. While the Union government grants exploration licenses under the 1948 Act, state governments retain authority over land acquisition and local approvals. This dual approval system creates implementation challenges, particularly for cross-state pipeline projects.

Recent amendments to various state land acquisition acts have introduced additional requirements for petroleum projects. States like Rajasthan and Gujarat have specific provisions for petroleum exploration activities, requiring compliance with state-specific environmental and social requirements beyond Union regulations.

Technology Integration and Digital Land Records

The integration of digital land records with petroleum exploration databases presents both opportunities and challenges. The government’s Digital India Land Records Modernization program aims to create integrated databases linking exploration licenses with land ownership records. However, implementation challenges persist due to varying state systems and data quality issues.

Blockchain technology implementation for land record management, as piloted in states like Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, could potentially streamline the interface between exploration licensing and land rights verification. These technological developments may reduce disputes and enhance transparency in the land acquisition process.

Future Directions and Reform Considerations

Legislative Harmonization and Single Window Clearances

The current fragmented regulatory landscape requires multiple approvals from different agencies for petroleum projects. The proposed single window clearance mechanism under the proposed Indian Hydrocarbon Vision 2030 aims to streamline approvals while maintaining regulatory oversight. This reform would integrate PNGRB authorizations with land acquisition approvals and environmental clearances, helping to clarify and protect oil and gas land rights in the process.

The Law Commission of India’s recommendations on land acquisition reform emphasize the need for time-bound clearances and transparent compensation mechanisms. These recommendations, if implemented, would significantly affect petroleum infrastructure development timelines and costs.

Emerging Technologies and Regulatory Adaptation

The advent of unconventional petroleum resources, including shale gas and coal bed methane, requires adaptation of existing legal frameworks. The 2018 amendment to include unconventional hydrocarbons in the petroleum definition represents initial regulatory adaptation, but comprehensive framework development remains pending.

Carbon capture and storage technologies for enhanced oil recovery present new land use challenges not adequately addressed in current legislation. The development of specific regulations for these technologies will require careful consideration of long-term land use rights and environmental obligations.

Conclusion

India’s oil and gas land rights framework represents a complex interplay between federal regulatory authority and state land rights, creating both opportunities and challenges for sector development. The PNGRB Act, the Petroleum and Minerals Pipelines (Acquisition of Right of User in Land) Act, 1962, and the exploration licensing system under the Oilfields (Regulation and Development) Act, 1948, together form a comprehensive but sometimes fragmented legal structure.

Recent Supreme Court jurisprudence, particularly the Mineral Area Development Authority decision, has clarified important aspects of mineral taxation while leaving certain petroleum-specific issues for future determination. The Court’s emphasis on state taxation powers, subject to express Parliamentary limitations, provides a framework for understanding the evolving federal-state dynamics in petroleum sector regulation.

The sector’s future development will likely require legislative harmonization to address the current fragmentation between regulatory authorization under the PNGRB Act and land acquisition processes. The proposed single window clearance mechanism and technology integration initiatives represent positive steps toward streamlining the regulatory interface.

As India pursues energy security objectives while balancing environmental and social concerns, the oil and gas land rights framework will continue evolving to address emerging challenges including unconventional resources, carbon management technologies, and digital transformation initiatives. Success in this evolution will depend on maintaining the delicate balance between federal regulatory oversight, state land rights, and private investment incentives essential for sector growth.

References

[1] The Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board Act, 2006, Act No. 19 of 2006. Available at: https://pngrb.gov.in/pdf/Act/ACT_PNGRB.pdf

[2] The Petroleum and Minerals Pipelines (Acquisition of Right of User in Land) Act, 1962, Act No. 50 of 1962. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/1424

[3] The Oilfields (Regulation and Development) Act, 1948, Act No. 53 of 1948

[4] Constitution of India, Article 246 and Seventh Schedule

[5] Mineral Area Development Authority v. Steel Authority of India Ltd., 2024 SCC OnLine SC 1796

[6] The Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board Act, 2006, Section 1(4)

[7] The Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board Act, 2006, Section 11(c)

[8] The Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board Act, 2006, Section 2(j)

[9] IMC Limited v. Union of India, Bombay High Court, 2024

Authorized and Published by Prapti Bhatt

Coal Mining Land Governance: Coal Bearing Areas Act, Land Restoration, and Post-Mining Use

Abstract

Coal mining land governance in India operates through a complex regulatory framework that encompasses acquisition, environmental protection, restoration, and post-mining land use. This article examines the legal architecture governing coal-bearing areas, analyzing the Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition and Development) Act, 1957, environmental compliance mechanisms, land restoration obligations, and emerging frameworks for post-mining land utilization. The analysis reveals significant challenges in balancing energy security requirements with environmental protection and community rights, while highlighting recent policy developments aimed at sustainable mining practices and just transition principles.

Introduction

India’s coal mining sector, contributing approximately 70% of the country’s electricity generation, operates within a unique legal framework that prioritizes state control over coal resources while addressing environmental and social concerns. The governance of coal mining land involves multiple regulatory layers, from initial acquisition under specialized legislation to complex restoration requirements and emerging post-mining utilization policies.

The regulatory landscape has evolved significantly since the enactment of the Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition and Development) Act, 1957, responding to changing environmental consciousness, tribal rights recognition, and sustainable development imperatives. Contemporary Coal Mining Land Governance must reconcile competing demands for energy security, environmental protection, community welfare, and economic development within constitutional and international law frameworks.

The intersection of mining law with environmental protection, forest rights, and land acquisition legislation creates a complex regulatory matrix that requires careful analysis to understand the practical implications for mining operations, affected communities, and long-term land use planning.

Legal Framework for Coal Land Acquisition

The Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition and Development) Act, 1957

The Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition and Development) Act, 1957 (CBA Act) represents the foundational legislation governing coal land acquisition in India. Enacted to establish “greater public control over the coal mining industry,” the Act provides for state acquisition of unworked land containing or likely to contain coal deposits. [1]

Section 4 of the CBA Act establishes the preliminary notification mechanism, stating that “whenever it appears to the Central Government that coal is likely to be obtained from land in any locality, it may, by notification in the Official Gazette, give notice of its intention to prospect for coal therein.” This provision grants extensive prospecting rights, including powers to “enter upon and survey any land,” “dig or bore into the sub-soil,” and “do all other acts necessary to prospect for coal.”

The prospecting notification under Section 4(1) remains valid for two years, extendable by one additional year, during which existing prospecting licenses and mining leases cease to have effect. This suspension mechanism ensures state monopoly over coal exploration in notified areas, reflecting the Act’s emphasis on centralized resource control.

Following prospecting confirmation, Section 7 empowers the Central Government to issue acquisition notices within the prescribed timeframe. The acquisition process involves mandatory consideration of objections under Section 8, followed by declaration under Section 9, which results in absolute vesting “free from all encumbrances” under Section 10.

The Act’s compensation framework, detailed in Section 13, provides for payment based on actual expenditure incurred rather than market value, distinguishing it from general land acquisition legislation. For prospecting licenses, compensation covers “reasonable and bona fide expenditure actually incurred,” including license costs, mapping expenses, infrastructure development, and other prospecting operations.

Integration with Contemporary Land Acquisition Law

The CBA Act operates alongside the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 (LARR Act), creating a dual regulatory framework. While coal-bearing land acquisition follows CBA Act procedures, ancillary infrastructure development typically requires LARR Act compliance.

This dual framework generates procedural complexities, as mining companies must navigate different compensation mechanisms, public consultation requirements, and approval processes depending on the specific purpose of land acquisition. The Ministry of Coal clarifies that “mining rights and surface rights of a single patch of land may not be acquired under different Acts,” ensuring procedural consistency for individual parcels. [2]

Recent policy developments indicate growing integration between these frameworks, with emphasis on harmonizing compensation standards and procedural safeguards. The proposed CBA Amendment Bill, 2024, includes provisions for land return and community benefit sharing, reflecting contemporary land rights perspectives.

Environmental Compliance Framework

Statutory Environmental Requirements

Coal mining operations must comply with multiple environmental statutes, creating a layered regulatory framework. The Environment Protection Act, 1986, and associated rules establish the foundation for environmental clearance requirements, while sector-specific regulations address mining-related environmental impacts.

Environmental clearance under the Environmental Impact Assessment Notification, 2006, requires comprehensive assessment of mining projects exceeding prescribed thresholds. Coal mining projects above 150 hectares require Category A clearance from the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, while smaller projects fall under Category B clearance from State Environment Impact Assessment Authorities.

The Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, governs forest land diversion for mining purposes, requiring prior approval for any non-forestry use of forest land. Coal mining projects frequently involve forest land diversion, necessitating compliance with compensatory afforestation requirements and payment of Net Present Value for forest ecosystem services.

Water pollution control follows the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, requiring consent to establish and operate from State Pollution Control Boards. Air quality management operates under the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981, with stringent monitoring requirements for particulate matter and gaseous emissions.

Progressive Restoration Obligations

The regulatory framework mandates concurrent restoration during mining operations rather than post-closure rehabilitation alone. Coal companies must submit detailed Mine Closure Plans as part of environmental clearance applications, specifying restoration timelines, methodologies, and financial provisions.

Recent directions from the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change make re-grassing mandatory in mined-out areas “to make them suitable for the growth of flora and fauna once the mining activity is complete.” [3] This requirement follows Supreme Court orders emphasizing restoration to conditions “fit for the growth of fodder, flora and fauna.”

The implementation of satellite surveillance for land reclamation monitoring represents a significant advancement in enforcement capabilities. Coal companies must demonstrate progressive restoration through regular satellite-based assessments, with remedial measures required for non-compliance.

Financial assurance mechanisms include environmental guarantees and restoration bonds, calculated based on restoration costs and maintained throughout mining operations. These instruments ensure availability of funds for restoration activities regardless of operator financial conditions.

Forest Rights and Tribal Land Protection

The Forest Rights Act, 2006 Framework

The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 (Forest Rights Act), establishes crucial protections for tribal communities affected by coal mining operations. The Act recognizes individual land rights up to 4 hectares for lands under cultivation as of December 13, 2005, and community forest rights over traditional forest resources.

Section 4(2) of the Forest Rights Act provides specific protections against displacement, requiring scientific establishment of relocation necessity, public consultation processes, and consent of affected Gram Sabhas. For coal mining projects, this creates mandatory consultation requirements with recognized forest rights holders before project approval.

The intersection of coal mining with forest rights generates complex legal issues, particularly regarding community forest resource rights over mining areas. The Act grants communities rights to “protect, regenerate, conserve or manage any community forest resource that they have been traditionally protecting and conserving for sustainable use.” [4]

Mining project approvals must demonstrate compliance with Forest Rights Act requirements, including completion of rights recognition processes and appropriate consultation with rights holders. Failure to follow these procedures can result in project delays or cancellation, as demonstrated in several high-profile cases.

Community Consent and Benefit Sharing

The Panchayats (Extension to the Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 (PESA), strengthens tribal self-governance rights in mining contexts. PESA requires Gram Sabha consent for land acquisition and mineral resource exploitation in Scheduled Areas, creating additional procedural requirements for coal mining projects.

Recent policy developments emphasize benefit sharing mechanisms for mining-affected communities. The District Mineral Foundation framework, established under the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Amendment Act, 2015, requires contribution of mining revenues for affected area development.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Orissa Mining Corporation vs. Ministry of Environment & Forest represents a landmark recognition of community rights in mining contexts. The Court upheld Gram Sabha authority to reject mining projects, establishing precedent for community consent requirements in natural resource extraction. [5]

Land Restoration and Reclamation Requirements

Technical Standards and Methodologies

Coal mining restoration follows detailed technical standards specified in environmental clearance conditions and mining plans. The restoration process involves backfilling of mining voids, overburden dump reclamation, soil reconstruction, and vegetation establishment using native species.

Backfilling operations must achieve stable slope angles and proper drainage to prevent soil erosion and water contamination. Overburden dumps require scientific design for long-term stability, with progressive reclamation as mining advances rather than deferred restoration.

Soil reconstruction involves systematic preservation of topsoil during mining operations and its replacement during restoration. The process requires maintenance of soil fertility through appropriate amendments and organic matter incorporation to support vegetation establishment.

Vegetation restoration emphasizes native species selection and ecological restoration principles rather than simple tree plantation. Recent guidelines promote biodiversity conservation through habitat restoration and corridor creation for wildlife movement.

Monitoring and Compliance Mechanisms

The regulatory framework establishes comprehensive monitoring requirements for restoration activities. Satellite-based monitoring provides regular assessment of restoration progress, with quarterly reports required from mining operators.

Ground-truthing activities verify satellite observations through field inspections by regulatory authorities. These inspections assess restoration quality, vegetation survival rates, and compliance with approved restoration plans.

Water quality monitoring ensures that restored areas do not generate acid mine drainage or other contamination. Long-term monitoring requirements extend beyond mining operations to verify restoration sustainability.

Independent third-party monitoring provides additional verification of restoration progress. Environmental consultants conduct annual assessments of restoration activities, with reports submitted to regulatory authorities and made publicly available.

Financial Mechanisms and Enforcement

Environmental guarantees secure financial resources for restoration activities throughout mining operations. The guarantee amount reflects restoration costs calculated according to standardized methodologies, with periodic revision based on cost inflation and technical developments.

Progressive release of guarantees follows demonstrated restoration achievement, with final release contingent on successful completion of all restoration obligations. This mechanism incentivizes timely restoration and ensures fund availability for corrective measures.

Enforcement actions for restoration non-compliance include stop-work orders, environmental compensation, and license cancellation. Recent amendments strengthen penalty provisions and enable faster enforcement action for environmental violations.

Bank guarantee mechanisms ensure financial security even in cases of operator bankruptcy or abandonment. These instruments provide regulatory authorities with direct access to restoration funds without relying on operator financial capacity.

Post-Mining Land Use and Repurposing

Policy Framework for Land Utilization

The Cabinet approval of policy for land use acquired under the CBA Act, 2021, represents a significant development in post-mining land governance. The policy provides a framework for utilizing lands that are “no longer suitable or economically viable for coal mining activities” or “from which coal has been mined out/de-coaled and such land has been reclaimed.” [6]

The policy specifically allows land use for “setting up washeries, coal gasification and coal-to-chemical plants,” “energy-related infrastructure,” and “rehabilitation and resettlement of Project Affected Families.” This framework maintains government company ownership while enabling leasing arrangements for specified purposes.

Leasing mechanisms follow “transparent, fair and competitive bid process” to achieve optimal value while preventing speculative land use. The policy establishes clear procedures for land allocation, lease terms, and performance monitoring to ensure productive utilization.

The integration of post-mining land use with renewable energy development reflects contemporary energy transition priorities. Coal companies can establish solar plants and other renewable infrastructure on restored mining areas, creating new revenue streams while supporting climate objectives.

Community-Centered Rehabilitation Models

Emerging approaches emphasize community participation in post-mining land use planning. The proposed “exact reclamation” model seeks to return restored land to original owners under corporate social responsibility frameworks, addressing land acquisition concerns while maintaining productive land use. [7]

Rehabilitation programs for Project Affected Families increasingly utilize post-mining land for resettlement purposes. This approach addresses displacement impacts while ensuring land productivity through planned development activities.

Skill development and livelihood programs prepare mining-dependent communities for post-mining economic activities. These programs focus on alternative employment opportunities in agriculture, forestry, small-scale industries, and service sectors.

Community forest management represents another avenue for post-mining land use, with restored areas designated for community forest resource management under Forest Rights Act provisions. This approach recognizes traditional ecological knowledge while providing sustainable livelihood opportunities.

Economic and Environmental Sustainability

Post-mining land use must achieve economic viability while maintaining environmental integrity. Sustainable land use models integrate economic development with ecological restoration, creating long-term value for communities and environment.

Agriculture development on restored mining land requires soil quality improvement and water resource development. Successful programs demonstrate productive agriculture on properly restored mining areas, providing food security and economic opportunities.

Eco-tourism development utilizes restored mining landscapes for recreational and educational purposes. Well-planned eco-tourism projects generate employment opportunities while showcasing successful restoration examples.

Carbon sequestration through forest restoration on post-mining land contributes to climate change mitigation while creating potential revenue through carbon credit mechanisms. These approaches align mining restoration with global climate objectives.

Challenges in Implementation and Compliance

Institutional Coordination Issues

The complexity of coal mining land governance creates significant coordination challenges among multiple regulatory authorities. Environmental clearances, forest approvals, tribal consultations, and mining permissions involve different agencies with varying timelines and requirements.

Delayed decision-making processes result from inadequate inter-agency coordination, creating uncertainty for mining operations and affected communities. Recent efforts to establish single-window clearance mechanisms aim to address these coordination challenges.

Capacity constraints affect regulatory implementation, particularly at state and district levels where technical expertise for environmental monitoring and restoration assessment may be limited. Training programs and technical assistance initiatives seek to address these capacity gaps.

Enforcement inconsistencies arise from varying interpretation of regulatory requirements across different jurisdictions. Standardized guidelines and regular training help ensure consistent implementation of environmental and social safeguards.

Mine Closure Implementation

India’s experience with formal mine closure reveals significant implementation challenges. Only three coal mines have achieved formal closure certificates despite guidelines introduced sixteen years ago, indicating systematic implementation problems. [8]

The slow pace of closure reflects complex procedural requirements, financial constraints, and institutional reluctance to relinquish land control. Recent identification of 299 mines for closure by Coal India Limited demonstrates growing attention to systematic closure implementation.

Financial constraints affect restoration quality and completion timelines. Many mining companies struggle to fund restoration activities adequately, leading to substandard restoration or abandoned sites requiring government intervention.

Lack of post-closure monitoring and maintenance affects restoration sustainability. Successful restoration requires long-term management beyond formal closure, necessitating institutional arrangements for ongoing stewardship as an essential part of Coal Mining Land Governance.

Community Rights and Displacement

Displacement of tribal and rural communities remains a persistent challenge in coal mining development. Despite legal protections, implementation gaps affect community rights recognition and rehabilitation effectiveness.

The intersection of traditional land rights with formal property systems creates legal uncertainties affecting compensation and rehabilitation. Community land tenure patterns often differ from formal legal recognition, complicating rights assessment and protection.

Inadequate consultation processes affect community participation in mining decisions. Meaningful consultation requires culturally appropriate mechanisms and adequate time for community decision-making, which formal procedures may not accommodate.

Gender-specific impacts of mining displacement receive insufficient attention in current frameworks. Women face particular challenges related to livelihood disruption, access to resources, and participation in rehabilitation programs, requiring targeted interventions. [9]

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Just Transition Framework Development

India’s development of mine closure frameworks with World Bank assistance emphasizes just transition principles focusing on “institutional governance, people and communities, and environmental reclamation and land repurposing.” [10] This approach recognizes the interconnected nature of environmental, social, and economic aspects of mining transitions.

The proposed RECLAIM framework represents a community engagement and development approach for mine closure and repurposing. This initiative emphasizes stakeholder participation, alternative livelihood development, and sustainable land use planning.

International cooperation on just transition provides technical and financial support for systematic mine closure implementation. Climate finance mechanisms may provide additional resources for restoration and alternative development activities.

Policy integration across sectors enables coordinated approaches to mining transitions. Integration of mining closure with renewable energy development, rural development, and environmental restoration creates synergistic opportunities for sustainable development.

Technological Innovation in Restoration

Advanced restoration technologies improve restoration outcomes while reducing costs and implementation timelines. Innovations include drone-based seeding, soil amendment techniques, and precision vegetation establishment methods.

Bioremidiation approaches utilize biological processes to address soil and water contamination issues. These technologies offer cost-effective solutions for legacy contamination while supporting ecosystem restoration objectives.

Digital monitoring systems provide real-time assessment of restoration progress and environmental compliance. Remote sensing, IoT sensors, and data analytics enable more effective monitoring and adaptive management.

Carbon capture and utilization technologies create opportunities for post-mining land use in climate change mitigation. These approaches may provide additional revenue streams while contributing to environmental objectives.

Regulatory Reform Initiatives

Proposed amendments to the CBA Act aim to modernize the regulatory framework while addressing contemporary land rights and environmental concerns. The Amendment Bill includes provisions for land return, benefit sharing, and enhanced community participation.

Integration of environmental and social safeguards within mining legislation seeks to streamline compliance while strengthening protection mechanisms. Unified environmental and social management systems reduce procedural complexity while improving outcomes.

Performance-based regulation emphasizes outcomes rather than prescriptive procedures, enabling innovation while maintaining environmental and social standards. This approach provides operators with flexibility in achieving restoration and community benefit objectives.

Strengthened enforcement mechanisms include enhanced penalties, faster dispute resolution, and improved monitoring capabilities. These reforms aim to ensure effective implementation of environmental and social safeguards throughout mining operations.

Case Law Analysis and Judicial Precedents

Supreme Court Jurisprudence on Mining and Environment

The Supreme Court has established important precedents regarding environmental protection in mining contexts. The Court’s emphasis on sustainable development principles requires balancing economic development with environmental protection and community rights, which directly shapes the evolution of coal mining land governance in India.

In environmental protection cases, the Court has consistently emphasized the precautionary principle and the polluter pays principle as fundamental to environmental jurisprudence. These principles require mining operators to demonstrate environmental safety and bear the costs of environmental protection and restoration.

The Court’s recognition of community rights in natural resource management, particularly in cases involving tribal communities, has strengthened legal protections for mining-affected populations. These decisions emphasize the importance of meaningful consultation and consent in mining project approval.

Constitutional interpretation regarding Article 21 (right to life) has expanded to include environmental rights, creating additional legal obligations for mining operators. This jurisprudence requires demonstration that mining operations do not compromise fundamental rights to clean environment and sustainable livelihoods.

Forest Rights and Mining Interface

Judicial decisions regarding the intersection of forest rights and mining have clarified the supremacy of community rights over mineral extraction in protected areas. The Niyamgiri case represents a landmark decision upholding Gram Sabha authority to reject mining projects affecting sacred sites and community rights.

Court interpretations of the Forest Rights Act emphasize the mandatory nature of rights recognition processes before any displacement or land acquisition. Mining projects cannot proceed without completing forest rights recognition and obtaining appropriate community consent.

The judicial emphasis on scientific assessment of relocation necessity requires mining proponents to demonstrate that alternative development approaches are not feasible. This standard creates significant procedural requirements for projects affecting forest rights holders.

Environmental court decisions increasingly recognize the interconnection between biodiversity conservation, community rights, and sustainable development. These decisions require integrated approaches to mining development that address ecological and social dimensions comprehensively, reinforcing the role of coal mining land governance in balancing competing interests.

Conclusion

Coal mining land governance in India represents a complex intersection of energy security requirements, environmental protection obligations, and community rights recognition. The regulatory framework has evolved from simple acquisition procedures to sophisticated environmental and social safeguard systems, reflecting broader changes in development paradigms and legal consciousness.

The Coal Bearing Areas Act, while providing effective mechanisms for state control over coal resources, requires modernization to address contemporary environmental and social concerns. Recent policy developments, including post-mining land use frameworks and just transition initiatives, demonstrate growing recognition of the need for sustainable mining practices.

Environmental compliance frameworks have strengthened significantly over recent decades, with mandatory restoration requirements, satellite monitoring, and financial guarantee mechanisms improving restoration outcomes. However, implementation challenges persist, particularly regarding mine closure completion and long-term restoration sustainability.

The recognition of forest rights and tribal community protections creates important legal safeguards while requiring careful integration with mining development procedures. Meaningful implementation of these protections demands genuine consultation processes, benefit sharing mechanisms, and alternative development opportunities for affected communities.

Post-mining land use represents an emerging frontier in mining governance, with significant potential for sustainable development outcomes. Successful implementation requires integrated planning, community participation, and long-term institutional commitments to restoration and alternative livelihood development.

The future of coal mining land governance depends on successful integration of environmental protection, community rights, and economic development within frameworks that support India’s energy transition objectives. This integration requires continued legal innovation, institutional capacity building, and stakeholder engagement to achieve sustainable outcomes for environment, communities, and national development.

Effective coal mining land governance ultimately requires recognition that mineral extraction is temporary while environmental and social impacts are long-term. Sustainable approaches must internalize these long-term costs and benefits within mining decision-making processes, ensuring that mineral development contributes to sustainable development rather than undermining environmental and social foundations for future generations.

References

[1] Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition and Development) Act, 1957, Preamble. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/13051/1/a1957-20.pdf

[2] Ministry of Coal. Land Acquisition Under CBA Act 1957. Available at: https://www.coal.gov.in/en/major-statistics/land-acq-under-cba-act-1957

[3] Government Makes Re-grassing of Mined-out Areas Mandatory. Mongabay India. Available at: https://india.mongabay.com/2020/01/government-makes-re-grassing-of-mined-out-areas-mandatory/

[4] The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006.

[5] Undoing Historical Injustice: The Role of the Forest Rights Act. Indian Law Review. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/24730580.2020.1783941

[6] Prime Minister’s Office. Cabinet Approves Policy for Use of Land Acquired under CBA Act, 1957. Available at: https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/news_updates/cabinet-approves-policy-for-use-of-land-acquired-under-the-coal-bearing-areas-acquisition-development-act-1957/

[7] Mishra, A.K. A New Model of Exact Reclamation of Post-mining Land. Journal of the Geological Society of India. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12594-017-0604-0

[8] India’s Coal Mine Closure Crisis Threatens Just Transition. The Wire.

[9] How Unplanned Coal Mine Closures are Affecting Dependent Communities. Mongabay India. Available at: https://india.mongabay.com/2024/03/how-unplanned-coal-mine-closures-in-india-are-affecting-dependent-communities-especially-women/

Published and written by Vishal Davda

Defence Land Administration: Legal Framework for Cantonment Acts, Land Management, and Civilian Interface in India

Introduction

Defence land administration in India represents a unique intersection of military requirements, civilian governance, and constitutional principles that has evolved over more than two centuries. With approximately 17.13 lakh acres of defence land spread across the country, including 2 lakh acres within 61 notified cantonments [1], the legal framework governing defence estates requires sophisticated balancing of strategic imperatives with civilian rights and democratic governance. The transition from the colonial-era Cantonments Act, 1924 to the modern Cantonments Act, 2006 [2] reflects India’s commitment to democratic decentralization while maintaining military operational effectiveness.

The constitutional foundation for defence land administration rests on Entry 3 of the Union List in the Seventh Schedule, which grants the Union Government exclusive authority over defence matters, including urban self-governance in cantonments [3]. This federal oversight operates through a complex regulatory matrix encompassing the Cantonments Act, 2006, Cantonment Land Administration Rules (CLAR) of 1925 and 1937 [4], Acquisition, Custody and Relinquishment (ACR) Rules, 1944 [5], and various judicial precedents that have shaped the civilian-military interface in defence territories.

The legal architecture governing defence land administration must address multiple competing demands: operational security requirements, civilian population needs within cantonment areas, property rights protection, environmental compliance, and democratic participation. The dual nature of cantonments as both military installations and civilian municipalities creates jurisdictional complexities that require careful navigation by defence authorities, civilian administrators, and judicial institutions.

Constitutional Framework and Legislative Evolution

Constitutional Basis for Defence Land Administration

The constitutional foundation for defence land administration emerges from the distribution of powers between the Union and State governments under the Seventh Schedule. Entry 3 of the Union List establishes defence as an exclusive Union subject, extending to “Naval, military and air force works” and including matters concerning land acquisition and administration for defence purposes. Article 243P(e) of the Constitution defines municipalities as “institutions of self-government,” [6] which becomes particularly relevant for cantonment boards that are deemed municipalities under this provision.

The 74th Constitutional Amendment Act, 1992, which introduced Part IXA relating to municipalities, significantly impacted cantonment governance. Section 10(2) of the Cantonments Act, 2006 explicitly states that “every Board shall be deemed to be a municipality under clause (e) of Article 243P of the Constitution” [2]. This constitutional recognition ensures that cantonment boards operate as urban local bodies while maintaining their special character as defence establishments.

The constitutional framework creates a unique federal arrangement where Union Government exercises direct control over municipal functions within cantonments, contrasting with the general pattern of state control over municipal administration. This arrangement reflects the strategic importance of maintaining unified command over defence territories while ensuring democratic governance for civilian populations.

The Cantonments Act, 2006: Modernizing Defence Governance

The Cantonments Act, 2006, which replaced the colonial-era legislation, represents a fundamental shift toward democratic governance in defence territories. The Act’s stated objective is “to consolidate and amend the law relating to the administration of cantonments with a view to impart greater democratisation, improvement of their financial base to make provisions for developmental activities” [2]. This legislative evolution recognizes the changing character of cantonments from purely military installations to mixed civilian-military communities.

Chapter II of the Act addresses the definition and delimitation of cantonments, empowering the Central Government to declare any area as a cantonment “where any part of the forces is quartered” or areas required “for the service of such forces” [2]. Section 4 provides for the establishment of cantonment boards, while Section 10 specifies the municipal status of these boards, ensuring they function as democratic institutions while serving defence requirements.

The Act establishes four categories of cantonments based on population criteria: Category I (above 50,000), Category II (10,000 to 50,000), Category III (2,500 to 10,000), and Category IV (below 2,500) [2]. This classification system enables differentiated governance structures appropriate to varying demographic and administrative requirements while maintaining consistent legal frameworks across all cantonment areas.

Integration with Municipal Constitutional Framework

The integration of cantonment boards with the constitutional framework for municipalities creates both opportunities and challenges. Article 243W empowers municipalities with “such powers and responsibilities as may be necessary to enable them to function as effective institutions of self-government” [7]. For cantonment boards, this constitutional mandate must be reconciled with military operational requirements and security considerations.

The Twelfth Schedule of the Constitution lists eighteen functions that may be entrusted to municipalities, including urban planning, water supply, public health, and fire services [7]. Cantonment boards exercise these functions within the constraints imposed by defence requirements, creating a unique model of civil-military cooperation in urban governance. The Station Commander serves as the ex-officio President of the cantonment board, ensuring military interests are represented in civilian governance processes.

Land Management Framework and Regulatory Structure

Cantonment Land Administration Rules (CLAR) Framework

The administration of defence land within cantonments operates under a sophisticated regulatory framework established by the Cantonment Land Administration Rules of 1925 and 1937 [4]. These rules, formulated under the original Cantonments Act, continue to govern land transactions and property rights within cantonment areas. Rule 3 of CLAR 1937 provides for the maintenance of a General Land Register (GLR) for all land within the cantonment, serving as the definitive record of rights and interests.

The CLAR framework distinguishes between different categories of land within cantonments, including military areas, civil areas, and bazaar areas. Civil areas accommodate civilian residents and commercial activities, while military areas remain under direct service control. This zoning approach facilitates the coexistence of civilian and military activities while maintaining operational security and administrative efficiency.

The rules establish detailed procedures for land allocation, lease execution, and property transfers within cantonments. Rule 27 of CLAR 1937 provides for the regularization of unauthorized occupations, subject to payment of appropriate charges and compliance with cantonment regulations. These provisions balance the need for orderly land administration with practical realities of mixed civilian-military occupation patterns.

ACR Rules for Extra-Cantonment Defence Lands

Defence lands situated outside notified cantonments, comprising approximately 15 lakh acres, are governed by the Acquisition, Custody and Relinquishment of Military Lands in India (ACR) Rules, 1944 [5]. These rules establish procedures for acquiring land for defence purposes, maintaining custody of defence properties, and relinquishing surplus lands to civilian authorities. The ACR framework operates through Defence Estates Officers who maintain Military Lands Registers (MLR) similar to the General Lands Registers maintained for cantonment areas.

The ACR Rules provide statutory authority for land acquisition necessary for defence installations, training areas, ranges, and associated infrastructure. Rule 14 of the ACR Rules establishes procedures for determining compensation for land acquired for military purposes, ensuring fair treatment of affected landowners while expediting acquisition processes essential for national security.

The historical development of the ACR framework reflects changing military requirements and administrative practices. Originally promulgated as the Acquisition, Custody and Relinquishment of Military Lands Rules, 1927, the current 1944 Rules were formulated to address expanded defence land requirements during World War II and subsequent military modernization programs.

The Role of Indian Defence Estates Service (IDES)

The Indian Defence Estates Service (IDES), established in the 1940s as the Military Lands and Cantonments Service, serves as the specialized administrative cadre responsible for defence land management and cantonment administration [8]. IDES officers function as Chief Executive Officers of cantonment boards and Defence Estates Officers for military lands outside cantonments, ensuring professional administration of defence properties while maintaining civilian-military coordination.

The IDES cadre currently comprises 189 officers managing 61 cantonments and 37 Defence Estates Office Circles across the country [8]. These officers exercise statutory powers under the Cantonments Act, CLAR, and ACR Rules, including authority to grant leases, regulate land use, collect revenue, and enforce compliance with defence land administration policies. The service operates under the Directorate General Defence Estates (DGDE), which formulates policies and coordinates defence land administration nationwide.

The professional expertise of IDES officers in land administration, property law, and municipal governance ensures effective management of defence estates while maintaining sensitivity to civilian needs and constitutional requirements. The service’s specialized training and experience enable navigation of complex legal and administrative challenges inherent in defence land management.

Civilian Interface and Democratic Governance

Cantonment Board Structure and Representation

The governance structure of cantonment boards reflects the unique dual character of these territories as both military installations and civilian municipalities. Each cantonment board consists of equal numbers of elected and nominated members, ensuring balanced representation of civilian and military interests. The Station Commander serves as the ex-officio President, while an IDES officer functions as Chief Executive Officer and Member-Secretary [2].

Elected members represent civilian residents through democratic processes governed by the Cantonment Electoral Rules, 2007. These elections follow principles established in the Constitution for municipal governance, including reservations for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and women. The democratic representation ensures civilian voices are heard in cantonment administration while maintaining military oversight of security-sensitive decisions.

Nominated members include representatives of various government departments and military units, ensuring technical expertise and interdepartmental coordination in cantonment governance. This mixed composition facilitates informed decision-making on complex issues requiring both civilian and military perspectives, from urban planning to security management.

Civilian Rights and Property Administration

Civilian residents within cantonments enjoy property rights and municipal services comparable to those available in civilian municipalities, subject to restrictions necessary for military security. The Cantonments Act, 2006 recognizes existing property rights while establishing procedures for their regulation and transfer. Section 10(2) ensures that cantonment boards implement Central Government schemes for social welfare, public health, hygiene, safety, water supply, sanitation, and education [2].

Property transactions within cantonments require compliance with both civilian property laws and military security regulations. The conversion of leasehold properties to freehold status, particularly in civil areas of cantonments, represents a significant policy development that enhances civilian property rights while maintaining defence oversight. These conversions are governed by detailed procedures ensuring compliance with cantonment regulations and appropriate compensation to defence authorities.

The interface between civilian property rights and military requirements occasionally generates conflicts requiring judicial intervention. Courts have consistently recognized the special character of cantonment areas while protecting legitimate civilian interests. The Supreme Court’s observation in various defence land cases emphasizes the need for transparent procedures and fair compensation when civilian interests are affected by military requirements.

Municipal Services and Civic Administration

Cantonment boards exercise municipal functions including water supply, sanitation, waste management, road maintenance, street lighting, and public health services. These functions are performed under the oversight of the Station Commander and Chief Executive Officer, ensuring coordination with military requirements and security considerations. The provision of quality municipal services attracts civilian residents to cantonment areas, creating economically viable mixed communities.

The financial base of cantonment boards derives from property taxes, service charges, fees, and grants from the Central Government. Section 344 of the Cantonments Act provides for the Central Government to pay service charges to cantonment boards for services provided to military installations [2]. This financial arrangement ensures adequate resources for municipal service delivery while recognizing the special burden imposed by military presence.

Educational institutions within cantonments, including schools managed by cantonment boards, serve both military and civilian populations. These institutions often achieve high standards due to disciplined environments and adequate resources, making cantonment areas attractive to civilian families. The integration of civilian and military children in cantonment schools promotes social cohesion and mutual understanding between communities.

Judicial Interpretation and Case Law Development

Supreme Court Jurisprudence on Defence Land Rights

The Supreme Court has developed substantial jurisprudence addressing the interface between defence requirements and civilian rights in cantonment areas. The landmark case of Sahodara Devi v. Government of India [9] established important principles regarding the regularization of unauthorized occupations under CLAR 1937. The Court recognized the authority of defence establishments to regularize unauthorized constructions subject to payment of appropriate charges and compliance with cantonment regulations.

Recent judicial observations by the Supreme Court regarding irregularities in defence land allotment to private entities highlight the importance of transparent procedures and accountability in defence land management. The Court’s concern about the conversion of cantonment land for commercial purposes without proper authorization underscores the need for rigorous compliance with statutory procedures and appropriate oversight mechanisms.

The judicial approach balances respect for defence requirements with protection of civilian rights and proper administration of public resources. Courts have emphasized that defence land, being public property held in trust for national security, must be administered transparently and in accordance with established legal procedures. Unauthorized diversions or irregular allotments violate public trust and undermine both military security and civilian confidence in defence administration.

High Court Decisions on Property Rights and Conversions

Various High Courts have addressed specific issues arising from the civilian-military interface in cantonment areas. The Allahabad High Court’s decision regarding the grant of leases under Rule 27 of CLAR 1937 established important precedents for the regularization of property rights in cantonment areas. These decisions emphasize the discretionary nature of regularization while requiring fair consideration of civilian interests and compliance with prescribed procedures.

The Karnataka High Court’s interpretation of land classification under CLAR 1937 in Shri Narendra Madhusudan Murkumbi v. Director General Defence Estates [10] clarified the authority of defence officials to reclassify lands within cantonments subject to prescribed procedures and appropriate approvals. The judgment emphasized the importance of maintaining accurate land records and following established procedures for land administration within cantonment areas.

High Court jurisprudence has consistently recognized the special character of cantonment areas while ensuring that administrative discretion is exercised fairly and in accordance with established legal principles. These decisions provide important guidance for defence administrators and civilian residents navigating the complex legal landscape of cantonment property administration.

Property Conversion and Freehold Rights

The conversion of leasehold properties to freehold status in civil areas of cantonments represents a significant development in defence land policy. This conversion process, governed by detailed guidelines and procedures, enables civilian residents to acquire full ownership rights while ensuring appropriate compensation to defence authorities. The policy reflects recognition of the permanent civilian character of established civil areas within cantonments.

The Supreme Court’s approach to property conversion cases emphasizes the need for transparent procedures, fair valuation, and proper authorization. The Court has noted that conversion policies must balance civilian property rights with defence requirements and ensure that public resources are properly utilized. Irregular conversions or inadequate compensation undermine both civilian confidence and defence interests.

The conversion process typically involves detailed surveys, valuation assessments, and payment of conversion charges calculated according to prescribed formulae. These procedures ensure that defence authorities receive fair compensation for relinquishing proprietary interests while enabling civilian residents to secure full ownership rights in their properties.

Challenges and Contemporary Issues

Security Considerations and Civilian Access