Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

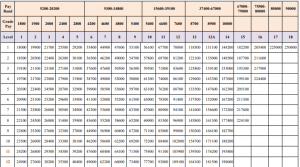

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

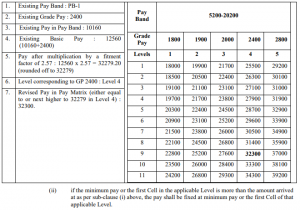

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

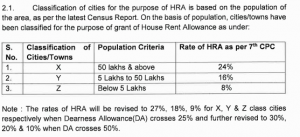

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

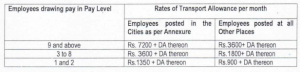

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Metro Rail Land Policy: Construction Act, Property Development, and Transit-Oriented Development

Executive Summary

Metro rail systems in India operate within a comprehensive legal framework that governs land acquisition, construction activities, property development, and transit-oriented development initiatives. The regulatory architecture encompasses the Metro Railways (Construction of Works) Act, 1978, the Metro Railway (Operations and Maintenance) Act, 2002, and the National Transit Oriented Development Policy, 2017, creating an integrated approach to urban mass transit infrastructure development. This analysis examines the statutory provisions, property development mechanisms, land value capture strategies, and transit-oriented development policies that shape contemporary metro rail land Policy in Indian metropolitan areas.

Introduction

Urban transportation infrastructure development in India has experienced unprecedented growth with over twenty cities implementing or planning metro rail systems across the country [1]. The legal framework governing metro rail land acquisition and policy has evolved significantly since the first underground metro system commenced operations in Kolkata in 1984. The Metropolitan cities of Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad, and numerous other urban centers now operate extensive metro networks requiring sophisticated metro rail land policy that balance public infrastructure needs with private property rights and commercial development opportunities [2].

The integration of land policy with transit infrastructure development represents a critical component of sustainable urban mobility planning, particularly as Indian cities grapple with rapid urbanization, traffic congestion, and environmental challenges associated with private vehicle dependence.

Statutory Framework: Metro Railways Construction Act, 1978

Legislative Foundation and Scope

The Metro Railways (Construction of Works) Act, 1978 serves as the primary legislation governing metro rail construction across Indian metropolitan areas [3]. Initially enacted to regulate the Kolkata Metro system, the Act was subsequently amended in 2009 to extend applicability to the National Capital Region and other metropolitan cities through central government notification after state consultation. This legislation forms a crucial part of the evolving metro rail land policy in India, shaping how urban transit projects are planned and executed.

The Act defines “metro railway” comprehensively to include all land within boundary marks, rail lines, sidings, yards, branches, stations, offices, ventilation systems, warehouses, workshops, manufacturing facilities, and associated infrastructure constructed for metro rail operations [3]. This expansive definition establishes the legal foundation for comprehensive land acquisition and development authority.

Land Acquisition Mechanisms

Section 6 of the Metro Railways (Construction of Works) Act, 1978 empowers metro railway administrations to acquire land, buildings, streets, roads, passages, or any rights of user or easement necessary for metro construction [3]. The acquisition process follows a structured procedure involving application to the Central Government, public notification, objection hearings, and formal declaration.

Section 7 mandates that upon receiving acquisition applications, the Central Government may issue notifications declaring intention to acquire specified properties for public purposes. The notification must provide brief descriptions of the land and intended metro railway project, with competent authorities required to publish notification substance in prescribed locations and manner [3].

Objection and Hearing Procedures

The Act establishes procedural safeguards through Section 9, providing twenty-one days from notification publication for interested persons to object to metro construction proposals [3]. Objections must be submitted in writing to competent authorities, who must provide hearing opportunities either personally, through agents, or via legal practitioners before issuing final orders allowing or disallowing objections.

Section 10 governs declaration procedures, stipulating that upon objection resolution or expiry of objection periods, competent authorities submit reports to the Central Government for formal acquisition declarations. Upon declaration publication, acquired land vests absolutely in the Central Government free from all encumbrances [3].

Compensation Framework

The compensation mechanism under Section 13 requires payment of amounts determined by competent authority orders, considering market value on notification dates, severance damages, consequential damages to other immovable property or earnings, and reasonable relocation expenses [3]. Appeal procedures to appellate authorities provide additional procedural protection for affected property owners.

Section 22 addresses compensation for construction prohibitions, requiring payment for losses sustained due to construction restrictions, including earnings diminution, market value reduction, demolition damages, and relocation expenses [3]. The comprehensive compensation framework reflects constitutional due process requirements while facilitating infrastructure development.

Contemporary Metro Rail Operations Framework

Metro Railway Operations and Maintenance Act, 2002

The Metro Railway (Operations and Maintenance) Act, 2002 governs operational aspects of metro rail systems, originally applying exclusively to Delhi but subsequently extended to other metropolitan areas excluding Kolkata [4]. The Act establishes Metro Railway Administrator (MRA) powers including property acquisition, development, alteration, and commercial utilization of metro railway land.

Section 6 grants MRA extensive powers to acquire, hold, and dispose of all property types, both movable and immovable, including rights to enter adjoining land for obstruction removal, signal visibility maintenance, and advertising revenue generation through hoarding erection [4]. These provisions enable comprehensive land utilization for both operational and commercial purposes.

Safety and Security Provisions

The operational framework incorporates stringent safety regulations including prohibitions on infectious disease carriers using metro systems, penalties for obstruction activities, and comprehensive enforcement mechanisms. Section 74 addresses sabotage with imprisonment terms ranging from three years to life, demonstrating the critical infrastructure protection priorities embedded within metro rail legislation [4].

Property Development and Commercial Utilization

Land Value Capture Mechanisms

Metro rail systems generate significant land value increases along transit corridors, creating opportunities for land value capture (LVC) to finance infrastructure development and operations. Research on the Bengaluru Metro demonstrates substantial property value appreciation near metro stations, though effective LVC implementation faces institutional and regulatory challenges [5].

The Bangalore Metro Rail Corporation Limited (BMRCL) has explored various LVC mechanisms including development-based revenue generation, though implementation has been constrained by fragmented land ownership, regulatory limitations, and insufficient plot amalgamation incentives [5]. Similar challenges affect other metro systems across India, highlighting the need for comprehensive policy reforms.

Commercial Development Strategies

Delhi Metro Rail Corporation (DMRC) has pioneered commercial property development through retail spaces, office complexes, and residential projects integrated with metro infrastructure [6]. The corporation’s property development initiatives demonstrate the potential for cross-subsidization of metro operations through strategic land utilization.

Mumbai Metro implementation incorporates private-public partnership models for property development, with estimated costs of ₹350 crore per kilometer requiring innovative financing mechanisms including real estate development opportunities [7]. The integration of commercial development with transit infrastructure represents a critical component of financial sustainability for metro rail projects.

Real Estate Development Regulations

Property development along metro corridors requires compliance with multiple regulatory frameworks including local development authorities, environmental clearances, and metro-specific safety requirements. Section 20 of the Metro Railways (Construction of Works) Act, 1978 mandates that proposed developments along metro alignments require metro railway administration approval, with conditions imposed considering safety requirements and prescribed matters [3].

The regulatory framework balances development opportunities with operational safety, requiring coordination between metro authorities, local planning bodies, and private developers to ensure compatible land use patterns.

Transit-Oriented Development Policy Framework

National Transit Oriented Development Policy, 2017

The National Transit Oriented Development (TOD) Policy, 2017 establishes guidelines for state and city-level TOD policy formulation, emphasizing moderate to high-density mixed-use development within 800 meters of transit stations [8]. The policy framework promotes compact, walkable communities that maximize transit accessibility while reducing automobile dependence.

TOD implementation requires integration of land use planning, transportation infrastructure, and urban design to create sustainable, livable communities. The policy emphasizes the importance of mixed land uses, pedestrian-friendly environments, and multimodal connectivity to achieve urban development objectives [8].

Delhi Master Plan TOD Integration

Delhi’s Master Plan 2041 incorporates comprehensive TOD provisions defining influence zones along Mass Rapid Transit System (MRTS) corridors, including metro, Regional Rapid Transit System (RRTS), and railway networks [9]. The plan establishes density controls, mixed-use zoning, parking limitations, and public-private partnership mechanisms to promote TOD implementation.

The influence zone framework distinguishes between intense zones with higher development potential and standard zones with moderate density increases, providing flexibility for context-sensitive development while maintaining transit accessibility objectives [9]. Floor Space Index (FSI) variations between zones incentivize higher density development near transit stations.

Implementation Challenges and Opportunities

TOD implementation in Indian cities faces significant challenges including institutional coordination requirements, financing constraints, regulatory complexity, and existing development patterns [10]. The multiplicity of agencies involved in land use planning, transportation provision, and infrastructure development necessitates enhanced coordination mechanisms.

Unified Metropolitan Transport Authorities (UMTAs) recommended by the National Urban Transport Policy provide institutional frameworks for improved coordination, though implementation remains limited across most metropolitan areas [10]. Urban Transport Funds (UTFs) offer potential mechanisms for integrated financing of TOD initiatives.

Land Value Capture and Financing Mechanisms

Bengaluru Metro Case Study Analysis

The Bengaluru Metro experience demonstrates both opportunities and challenges in implementing land value capture for metro rail financing. Despite operational profitability, loan repayment timelines extending four decades highlight the importance of supplementary revenue generation through property development and land value capture [5].

BMRCL’s exploration of multiple LVC mechanisms including betterment levies, development charges, and property development partnerships reveals the complexity of implementing effective value capture in Indian urban contexts. Spatial considerations including inner-city versus peripheral development patterns significantly influence LVC potential.

Regulatory and Institutional Barriers

Existing planning regulations often fail to support TOD objectives, with small plot sizes, fragmented ownership, and inadequate amalgamation incentives limiting development potential. Setback requirements, ground coverage restrictions, and outdated zoning provisions constrain the ability to achieve desired density levels near transit stations [5].

The separation of land use planning authority from transit planning and implementation creates coordination challenges that impede effective TOD and LVC implementation. Integrated institutional frameworks and regulatory reforms are essential for realizing the full potential of transit-oriented development.

Financial Innovation and Public-Private Partnerships

Metro rail financing increasingly relies on innovative mechanisms including public-private partnerships, development rights transfers, and cross-subsidization through commercial property development. The success of these approaches depends on regulatory flexibility, institutional capacity, and market conditions that support private sector participation.

Land acquisition costs representing significant portions of total project expenses highlight the importance of strategic land assembly and value capture to improve project financial viability. The Namma Metro Phase 3 experience demonstrates ongoing challenges in land acquisition despite offering compensation at 200% of market value [11].

Urban Design and Multimodal Integration

Station Area Development Standards

TOD implementation requires comprehensive urban design standards that promote walkability, cycling infrastructure, and seamless multimodal connectivity. The integration of metro stations with bus terminals, auto-rickshaw stands, and non-motorized transport facilities enhances overall system accessibility and ridership.

Pedestrian infrastructure including covered walkways, escalators, elevators, and weather protection systems significantly influence TOD success by improving first and last-mile connectivity. The quality of pedestrian environments directly affects transit usage patterns and commercial development viability around stations.

Mixed-Use Development Integration

Successful TOD requires strategic integration of residential, commercial, office, and institutional uses within walking distance of transit stations. Zoning regulations must provide flexibility for mixed-use development while maintaining compatibility between different land use types.

The promotion of affordable housing within TOD areas addresses social equity concerns while supporting transit ridership through resident proximity to employment centers and services. Inclusionary housing policies and cross-subsidization mechanisms can facilitate affordable housing integration within market-rate developments.

Environmental and Sustainability Considerations

Carbon Emission Reduction

Metro rail systems contribute significantly to urban carbon emission reduction through modal shift from private vehicles to public transportation. The Delhi Metro’s recognition by the United Nations as the first metro system to receive carbon credits for greenhouse gas emission reduction demonstrates the environmental benefits of well-designed transit systems [6].

TOD policies that reduce automobile dependence and promote compact development patterns further enhance environmental benefits through reduced energy consumption, lower infrastructure costs per capita, and preservation of agricultural and natural areas through controlled urban growth.

Green Building Integration

Sustainable building practices within TOD areas, including energy-efficient design, renewable energy systems, water conservation, and waste management, contribute to overall environmental objectives and form an important aspect of metro rail land policy in India. Green building certification programs and incentive mechanisms can promote sustainable development practices within transit corridors.

The integration of green infrastructure including parks, urban forests, and stormwater management systems within TOD areas enhances livability while providing environmental services. Climate-responsive design principles become increasingly important as cities adapt to changing environmental conditions.

Comparative Analysis: International Best Practices

Asian Development Models

Cities like Hong Kong, Singapore, and Tokyo demonstrate successful integration of transit development with property development through comprehensive planning frameworks and institutional coordination. The Hong Kong Mass Transit Railway Corporation’s property development model provides significant revenue streams that support system expansion and operations.

Japanese Joint Development (JD) practices integrate railway stations with commercial and residential development, creating vibrant urban centers that support both transit ridership and economic development. These models offer valuable lessons for Indian cities seeking to optimize land value capture and TOD implementation.

Financing and Governance Innovations

International experience demonstrates the importance of integrated governance structures that coordinate transportation planning, land use regulation, and infrastructure financing. Special purpose vehicles, development authorities, and regional coordination mechanisms provide institutional frameworks for effective TOD implementation.

Value capture mechanisms including betterment taxes, special assessment districts, and development impact fees offer potential revenue sources for transit infrastructure while ensuring that property owners who benefit from accessibility improvements contribute to system financing.

Future Directions and Policy Recommendations

Regulatory Reform Priorities

Comprehensive zoning reform to support mixed-use development, increased density near transit stations, and reduced parking requirements represents a critical priority for effective TOD implementation. Model zoning ordinances and form-based codes can provide templates for local adaptation while ensuring consistency with TOD objectives.

Streamlined approval processes for TOD projects including single-window clearances, fast-track permitting, and coordinated agency review can reduce development costs and timelines while maintaining appropriate regulatory oversight.

Institutional Capacity Development

The establishment of UMTAs in all metropolitan areas with metro rail systems would enhance coordination between transportation planning, land use regulation, and infrastructure development. These authorities require adequate funding, technical expertise, and regulatory authority to effectively implement integrated transportation and land use policies.

Professional capacity development for planners, engineers, and administrators involved in TOD implementation ensures that technical expertise keeps pace with policy innovation and project complexity. Training programs, professional exchange, and knowledge sharing platforms support institutional learning and best practice dissemination.

Technology Integration

Digital platforms for land records management, development application processing, and project monitoring can improve transparency, efficiency, and coordination among multiple agencies involved in TOD implementation. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and data analytics support evidence-based planning and performance monitoring.

Smart city initiatives can leverage technology to optimize transit operations, improve passenger experience, and enhance land use coordination. Real-time information systems, mobile applications, and integrated payment platforms support multimodal connectivity and system usability.

Conclusion

Metro rail land policy in India encompasses a sophisticated regulatory framework that addresses construction requirements, property development opportunities, and transit-oriented development objectives. The evolution from single-city legislation to comprehensive national policies reflects the growing recognition of metro rail systems as critical urban infrastructure requiring integrated approaches to land use and transportation planning.

The success of contemporary metro rail development depends on effective coordination between statutory frameworks, institutional mechanisms, and market forces that shape urban development patterns. The Metro Railways (Construction of Works) Act, 1978 provides the foundational legal authority for land acquisition and construction activities, while operational legislation and TOD policies create frameworks for sustainable development and revenue generation.

Property development and land value capture offer significant opportunities for metro rail system financing and urban development, though implementation requires regulatory reforms, institutional coordination, and innovative financing mechanisms. The experience of cities like Delhi, Mumbai, and Bengaluru demonstrates both the potential benefits and implementation challenges associated with transit-oriented development in Indian urban contexts.

Future policy development must address the complex interplay between regulatory frameworks, institutional capacity, financing mechanisms, and market dynamics that influence metro rail land policy effectiveness. The integration of environmental sustainability, social equity, and economic development objectives within comprehensive policy frameworks will determine the long-term success of metro rail systems in supporting sustainable urban development across India’s rapidly growing metropolitan areas.

The continued evolution of metro rail land policy must respond to changing urban dynamics, technological innovations, and environmental challenges while maintaining focus on the fundamental objective of providing efficient, accessible, and sustainable urban transportation infrastructure that serves all segments of society.

References

[1] JLRJS. (2023). The Metro Railways (Construction of Works) Act, 1978: Empowering Efficient Urban Transportation. Available at: https://jlrjs.com/the-metro-railways-construction-of-works-act-1978-empowering-efficient-urban-transportation/

[2] Wikipedia. (2024). Delhi Metro. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delhi_Metro

[3] Government of India. (1978). The Metro Railways (Construction of Works) Act, 1978. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1737/1/197833.pdf

[5] World Resources Institute. (2021). Synergizing Land Value Capture and Transit-Oriented Development: A Study of Bengaluru Metro. Available at: https://www.wri.org/research/synergizing-land-value-capture-tod

[6] Delhi Metro Rail Corporation. (2024). Property Development.

[7] Wikipedia. (2025). Mumbai Metro. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mumbai_Metro

[8] National Institute of Urban Affairs. (2017). Transit Oriented Development.

[9] ResearchGate. (2016). Transit Oriented Development Manual: Delhi TOD Policy and Regulations Interpretation. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329736642_Transit_Oriented_development_Manual_Delhi_TOD_policy_and_regulations_interpretation

[10] SlideShare. (2017). Implementing Transit Oriented Development in India. Available at: https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/implementing-transit-oriented-development-in-india/71221534

[11] Metro Rail News. (2024). Namma Metro Phase 3: BMRCL Faces Hurdles in Land Acquisition. Available at: https://metrorailnews.in/namma-metro-phase-3-bmrcl-faces-hurdles-in-land-acquisition/

Published and Authorized by Dhrutika Barad

Power Sector Land Rights: Electricity Act 2003, Transmission Corridors, and ROW Management

Introduction

The development of India’s electricity transmission infrastructure operates within a complex legal framework governing land acquisition and right-of-way (RoW) management. The legal paradigm for power sector land rights has evolved significantly since the enactment of the Electricity Act, 2003, establishing a regulatory architecture that balances public utility requirements with property rights protection. This framework encompasses statutory provisions, regulatory guidelines, and judicial interpretations that collectively govern how transmission utilities acquire and maintain access to land corridors essential for electricity infrastructure.

The transmission sector faces mounting challenges in securing power sector land rights as urbanization intensifies and environmental consciousness grows. Current estimates indicate that India’s transmission network capacity increased to 7.4 lakh MVA by March 2017, representing a 40% growth from 5.3 lakh MVA in March 2014 [1]. However, this expansion has been accompanied by increasing difficulties in obtaining right-of-way clearances and land access for transmission infrastructure, particularly in densely populated areas and environmentally sensitive zones.

Legal Framework Under the Electricity Act 2003

Statutory Provisions for Transmission Infrastructure

The Electricity Act, 2003 establishes the foundational legal framework for transmission line development and land acquisition, forming the statutory core of power sector land rights in India. Section 9 of the Act mandates that electricity supply from captive generating plants through the grid shall be regulated, while conferring rights of open access subject to transmission facility availability as determined by the Central Transmission Utility (CTU) or State Transmission Utility (STU) [2]. This provision creates the legal basis for transmission corridor development by establishing the statutory right to grid connectivity.

Section 14 of the Electricity Act, 2003 requires appropriate commissions to grant transmission licenses to qualified persons for electricity transmission within specified areas. The Act deems CTU, STUs, and appropriate governments engaged in transmission activities as licensed entities, thereby establishing clear regulatory authority over transmission infrastructure development. Under Section 40, transmission licensees bear the statutory duty to build, maintain, and operate efficient, coordinated, and economical transmission systems, creating legal obligations that justify land acquisition powers.

Powers of Land Access and Infrastructure Development

Section 67 of the Electricity Act, 2003 constitutes the primary statutory provision empowering licensees to access land for transmission infrastructure. This section permits licensees to open and break up soil and pavement of streets, railways, or tramways; open and break up sewers, drains, or tunnels; alter the position of existing lines, works, or pipes; lay down electric lines, electrical plant, and other works; repair, alter, or remove the same; and perform all acts necessary for transmission or supply of electricity [3].

The provision mandates that licensees cause minimal damage, detriment, and inconvenience while making full compensation for any damage caused. Where differences or disputes arise, including compensation amount disputes, the matter shall be determined by the appropriate commission. This creates a structured legal mechanism for resolving conflicts between transmission requirements and property rights.

Section 68 of the Electricity Act, 2003 addresses overhead line management, empowering Executive Magistrates or specified authorities to order removal of trees, structures, or objects that interrupt or interfere with electricity transmission. The provision requires reasonable compensation for pre-existing trees, recoverable from the licensee, establishing a balance between transmission operational requirements and property owner interests.

Regulatory Framework and Recent Developments

Central Electricity Authority Regulations 2022

The Central Electricity Authority (Technical Standards for Construction of Electrical Plants and Electric Lines) Regulations, 2022 establish detailed technical standards governing transmission line construction and RoW requirements. Schedule VII of these regulations defines specific RoW corridor specifications that form the basis for compensation calculations under recent Ministry of Power guidelines [4]. These regulations superseded earlier 2010 technical standards, reflecting technological advancements and evolving safety requirements in transmission infrastructure development.

The 2022 CEA Regulations incorporate provisions for contemporary technological options including monopole towers and High Temperature Low Sag (HTLS) conductors, which can reduce RoW width requirements. The regulations acknowledge that monopole structures require reduced footprints and fewer components, though they involve higher costs and transportation difficulties. This technological evolution has implications for land acquisition strategies and compensation frameworks.

Ministry of Power RoW Compensation Guidelines 2024

On June 14, 2024, the Ministry of Power issued revised guidelines for RoW compensation, superseding previous guidelines from October 15, 2015, June 16, 2020, and June 27, 2023. These guidelines apply exclusively to transmission lines of 66 kV and above, excluding sub-transmission and distribution lines below this voltage threshold [5]. The compensation framework establishes standardized rates based on land values as determined by circle rates, guideline values, or Stamp Act rates.

Under the 2024 guidelines, tower base compensation equals 200% of land value for the area enclosed by tower legs at ground level plus an additional one-meter extension on each side. RoW corridor compensation equals 30% of land value for the corridor area as defined in Schedule VII of the CEA Regulations 2022. These rates represent significant increases from earlier compensation structures, reflecting government recognition of landowner concerns and project delay issues.

The guidelines mandate one-time, upfront compensation payments through digital methods including Aadhaar-Enabled Payment System (AEPS) and Unified Payments Interface (UPI) where feasible. District Magistrates, District Collectors, or Deputy Commissioners determine compensation based on prevailing market rates where these exceed statutory rates. States and union territories may adopt these guidelines entirely or issue modified versions, with central guidelines applying in the absence of state-specific frameworks.

Implementation Mechanisms and Procedural Requirements

Land Acquisition Process

The transmission line land acquisition process operates through a structured methodology beginning with route survey and landowner identification. During check surveys at the execution stage, landowners whose properties fall within transmission line RoW are documented in accordance with Regulation 8a(B) of the CEA Regulations 2022. Transmission Service Providers (TSPs) bear responsibility for identifying landowners, issuing notices to proceed, and collecting necessary documentation including proof of identity and ownership, reflecting the legal safeguards built into power sector land rights.

Revenue officials verify land records against revenue maps to ensure accuracy in ownership determination and area calculations. For properties with multiple owners, TSPs must secure no-objection certificates from all co-owners, properly attested by village officials and revenue authorities. This process ensures legal clarity and prevents subsequent disputes regarding compensation entitlement.

Measurement procedures require TSP representatives to measure tower footing and corridor areas in the presence of landowners, obtaining signatures from both landowners and revenue officials on measurement sheets. This participatory approach enhances transparency and reduces potential conflicts over area calculations and compensation amounts.

Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

The Electricity Act, 2003 establishes dispute resolution mechanisms through appropriate commissions, which possess jurisdiction over compensation disputes under Section 67. Where differences arise regarding land rates or compensation amounts, District Magistrates or authorized magistrates address issues and determine appropriate compensation levels. This hierarchical approach provides multiple avenues for dispute resolution while maintaining administrative efficiency.

Recent judicial interpretations have clarified that transmission line installation does not constitute property acquisition under Article 30(1A) of the Constitution of India. In a significant 2023 Calcutta High Court decision, the court held that drawing high-tension lines does not amount to property acquisition, distinguishing transmission easements from permanent land acquisition [6]. This interpretation supports utility rights while clarifying constitutional limitations on transmission infrastructure challenges.

Environmental and Urban Planning Considerations

Forest and Environmental Clearances

Transmission line development in forested areas requires compliance with the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, and the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. These statutes impose additional procedural requirements beyond basic land acquisition processes, including environmental impact assessments and compensatory afforestation obligations. The Environmental (Protection) Act, 1986 further regulates transmission projects that may impact ecological systems.

Forest authorities maintain jurisdiction over scheduled trees including teak, while horticulture departments oversee fruit-bearing trees and agriculture departments assess crop damage values. The Rubber Board regulates compensation for rubber trees in applicable regions. This multi-agency approach ensures sector-specific expertise in damage assessment while complicating coordination requirements for transmission developers.

Urban Area Challenges and Technological Solutions

Urban transmission corridor development faces increasing constraints due to space limitations, safety concerns, and property values. The 2024 guidelines specifically address urban area challenges by recommending various technological options to optimize space usage in RoW-constrained areas. These include steel pole structures, narrow-based lattice towers, multi-circuit and multi-voltage towers, single-side stringing with lattice or steel poles, cross-linked polyethylene underground cables, gas-insulated lines, compact towers with insulated cross-arms, and voltage source converter-based high-voltage direct current systems [7].

The selection of appropriate technology depends on RoW reduction potential, implementation feasibility, and overall cost considerations. While advanced technologies can reduce land requirements, they often involve higher capital costs and specialized technical requirements that may not be suitable for all geographic contexts.

Compensation Structures and Financial Frameworks

Current Compensation Rates and Calculation Methods

The 2024 Ministry of Power guidelines establish a two-tier compensation structure addressing both permanent tower base occupation and corridor restrictions. Tower base compensation at 200% of land value reflects the permanent nature of tower foundation occupation and associated access requirements. The 30% corridor compensation acknowledges reduced land utility due to height restrictions and safety clearances while permitting continued agricultural or other compatible land uses.

Land value determination follows a hierarchical approach beginning with official rates including circle rates, guideline values, or Stamp Act rates. Where market rates exceed these official values, compensation calculations utilize prevailing market rates as determined by competent district authorities. This mechanism ensures compensation reflects actual economic impact rather than potentially outdated official valuations.

Alternative Compensation Mechanisms

The guidelines recognize alternative compensation methods including Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) policies implemented by state and union territory governments. Where landowners accept TDR or other alternative compensation arrangements, licensees must deposit equivalent compensation amounts with relevant corporations, municipalities, local development authorities, or state governments. This flexibility accommodates varying local conditions and landowner preferences while ensuring adequate compensation provision.

Digital payment mechanisms including AEPS and UPI facilitate transparent and efficient compensation disbursement. The preference for digital payments enhances accountability and reduces corruption risks while providing clear documentation of compensation transactions for both regulatory compliance and dispute prevention purposes.

Recent Judicial Developments and Case Law

Constitutional and Property Rights Perspectives

Recent judicial decisions have clarified the relationship between transmission line development and fundamental property rights. The Calcutta High Court’s 2023 decision in the matter concerning West Bengal State Electricity Transmission Co. Ltd. established that high-tension transmission line installation does not constitute property acquisition under Article 30(1A) of the Constitution. The court emphasized that transmission lines serve substantial public interests while distinguishing between easement rights and permanent acquisition [6].

This judicial interpretation supports the legal framework established by the Electricity Act, 2003 and Telegraph Act, 1885, confirming that transmission utilities possess statutory rights to establish necessary infrastructure without formal land acquisition procedures. The decision clarifies that compensation claims should be assessed upon completion of work rather than treated as acquisition proceedings, providing legal certainty for transmission development while preserving landowner compensation rights.

Eminent Domain and Public Purpose Considerations

The Supreme Court has consistently recognized electricity transmission as serving legitimate public purposes justifying eminent domain exercise where necessary. The Court’s emphasis on deference to legislative determinations of public use applies to transmission infrastructure development, provided that such determinations possess reasonable foundation and serve genuine public interests, thereby reinforcing the constitutional basis of power sector land rights.

Recent Supreme Court guidance on land acquisition constitutional tests emphasizes procedural rights including adequate notice, fair compensation, and due process protections. These principles apply to transmission line development where formal acquisition procedures are required, ensuring constitutional compliance while facilitating infrastructure development for public benefit.

Interstate and Central Government Coordination

Role of Central Transmission Utility

The Central Transmission Utility plays a pivotal role in interstate transmission corridor development and coordination. CTU responsibilities include ensuring adequate transmission facility availability for open access rights, coordinating with generating companies for electricity transmission, and maintaining grid standards for efficient system operation. These functions require CTU to balance competing demands for transmission capacity while ensuring equitable access for all grid users.

CTU coordination with State Transmission Utilities becomes essential for interstate transmission projects that cross multiple jurisdictions. The legal framework requires coordination mechanisms that respect state autonomy while ensuring national grid integrity and efficiency. This balance reflects constitutional principles governing federal-state relationships in infrastructure development.

Central Government Policy Initiatives

The Central Government has recognized transmission corridor development as essential for renewable energy integration and grid modernization. Recent policy initiatives include the Green Energy Corridor project and interstate transmission system strengthening programs designed to accommodate increased renewable energy capacity. These initiatives require coordinated land acquisition strategies and standardized compensation frameworks to ensure efficient implementation.

The 2024 RoW compensation guidelines represent one element of broader government efforts to address transmission development constraints. By standardizing compensation calculations and establishing transparent procedures, the guidelines aim to reduce project delays and facilitate renewable energy target achievement while ensuring fair treatment of affected landowners.

Future Outlook and Emerging Challenges

Technological Evolution and Land Use Optimization

Advancing transmission technologies offer potential solutions to land acquisition challenges through reduced RoW requirements and enhanced system efficiency. High Temperature Low Sag conductors, compact tower designs, and underground cable technologies can minimize land impacts while maintaining system reliability. However, technology adoption requires careful cost-benefit analysis and consideration of local geographic and economic conditions.

The Central Electricity Authority’s recent report on RoW width calculation for contemporary technological options provides guidance for optimizing land use in transmission corridor development. This technical guidance supports informed decision-making regarding technology selection and compensation framework application in specific project contexts.

Environmental and Social Impact Management

Growing environmental consciousness and community awareness require enhanced attention to environmental and social impact management in transmission development. The legal framework must evolve to address climate change considerations, biodiversity protection requirements, and community consultation processes while maintaining infrastructure development efficiency.

Future regulatory developments may incorporate more sophisticated environmental assessment requirements and community engagement protocols. These developments will require coordination between electricity sector regulators and environmental authorities to ensure integrated decision-making processes that address multiple policy objectives.

Conclusion

The legal framework governing power sector land rights in India represents a sophisticated balance between public infrastructure requirements and private property protection. The Electricity Act, 2003 provides foundational statutory authority for transmission development, while recent regulatory developments including the 2024 Ministry of Power guidelines establish practical mechanisms for fair compensation and efficient project implementation.

Current challenges in transmission corridor development reflect broader tensions between infrastructure modernization imperatives and property rights protection. The legal system’s evolution toward standardized compensation frameworks and transparent procedures demonstrates governmental recognition of these challenges while maintaining commitment to electricity sector development objectives.

Future success in power sector land rights management will depend on continued coordination between legal frameworks, technological innovation, and stakeholder engagement processes. The balance achieved between utility operational requirements and landowner interests will significantly influence India’s capacity to achieve renewable energy targets and grid modernization objectives while maintaining social and environmental sustainability standards.

The emerging legal paradigm emphasizes procedural transparency, fair compensation, and technological optimization as key elements in sustainable transmission infrastructure development. This approach provides a foundation for addressing future challenges while preserving the legal certainty necessary for continued investment in India’s electricity transmission infrastructure.

References

[1] SCC Times. (2021). Transmission of Electricity. Retrieved from https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2018/01/24/transmission-of-electricity/

[3] EPR Magazine. (2023). Right of Way (ROW) Challenges in the Construction of Transmission lines. Retrieved from https://www.eprmagazine.com/special-report/right-of-way-row-challenges-in-the-construction-of-transmission-lines/

[5] Mercom India. (2024). Government Issues Compensation Guidelines for Transmission Line Right of Way. Retrieved from https://www.mercomindia.com/compensation-guidelines-transmission-line

[6] SCC Blog. (2023). High Tension line not constitute property acquisition under Article 30(1A) of Constitution of India: Calcutta High Court. Retrieved from https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2023/09/27/high-tension-line-not-constitute-property-acquisition-under-article-301a-of-constitution-of-india-cal-hc-scc-blog/

[7] Power Line Magazine. (2024). Optimising Space Usage: MoP releases guidelines for RoW compensation. Retrieved from https://powerline.net.in/2024/07/30/optimising-space-usage-mop-releases-guidelines-for-row-compensation/

[8] TND India. (2024). CEA releases report on right-of-way width calculation. Retrieved from https://www.tndindia.com/cea-releases-report-on-right-of-way-width-calculation/

[9] BTG Advaya. (2024). Revised RoW Compensation Guidelines for Transmission Lines. Retrieved from https://www.btgadvaya.com/post/revised-row-compensation-guidelines-for-transmission-lines

Private Limited Company Registration Online in India – Step-by-Step Guide

Starting a new business in India often comes with the big question: Which type of company should I register? For most entrepreneurs, the safest and most trusted option is Private Limited Company Registration Online in India. It gives your business a legal identity, protects your assets, and builds credibility with banks, investors, and customers.

The entire process of registering a private limited company online can be done through the MCA (Ministry of Corporate Affairs) portal using the SPICe+ form. No need to visit government offices—everything is digital and streamlined.

Quick Snapshot

- What you get: A separate legal entity, limited liability, and better funding options.

- Where it happens: MCA (Ministry of Corporate Affairs) portal, using the integrated SPICe+

form. - How long it takes: Usually 5–10 working days (if documents are clean and the name is

approved). - What you’ll need: KYC docs for directors/shareholders, registered office proof, and a few

basic details.

Why choose a Private Limited Company Registration Online in India?

Out of all the business structures available in India, a Private Limited Company registration is the most flexible and reliable. Here’s why:

Limited liability: Your assets stay protected.

- Investor-friendly: VCs, banks, and serious clients prefer Pvt Ltd.

- Separate legal identity: more credibility and easier contracts.

- ESOPs & scaling: Easy to issue shares and bring in talent.

Short answer: If you’re building for scale, Pvt Ltd is usually the best fit.

Who can apply for Private Limited Company Registration Online in India?

- Directors: Minimum 2; at least one resident in India.

- Shareholders: Minimum 2 (can be the same people as directors).

- Capital: No minimum paid-up capital requirement.

- Registered office: Must have an address in India.

Documents Required for Private Limited Company Registration Online in India

To complete the registration smoothly, you’ll need a few basic documents from the directors, shareholders, and the registered office.

- For Directors/Shareholders: PAN (or Passport for foreigners), one ID proof, and recent

address proof. - For Registered Office: Latest utility bill, rent/ownership proof, and NOC if rented.

- Other: 2–3 name options and a short business activity description.

Step by Step Process for Private Limited Company Registration Online in India

Here is the process of private limited company registration online in India you’ll follow on the MCA

portal.

Step 1: Get Digital Signatures (DSC)

Every proposed director needs a DSC for e-filings. It’s quick, done via verified providers. Keep your KYC handy.

Step 2: DIN (Director Identification Number)

If you’re a new director, DIN is allotted within the SPICe+ filing itself (no separate pre-application needed).

Step 3: Company Name Approval – SPICe+ (Part A)

Apply for Company Name Approval under SPICe+ Part A.

Tips:

- Choose a distinct name (check the MCA database and do a basic trademark search).

- Keep 2–3 options ready.

Confident about your name? You can jump straight to Part B and file name + incorporation together.

Step 4: Fill SPICe+ (Part B) + Linked Forms

This is the core of the Private Limited Company registration online in India.

You’ll complete:

- SPICe+ Part B (main incorporation details)

- e-MOA (INC-33) and e-AOA (INC-34)

- AGILE-PRO-S (PAN, TAN, optional GST, EPFO, ESIC, Profession Tax—state-wise—and

even bank account) - INC-9 declaration (auto-generated for most cases)

Double-check director details, shareholding, registered office, and object clause (business activity).

Step 5: Pay Government Fees & Stamp Duty

Fees vary by state and authorized capital. You’ll also pay for PAN & TAN. This is where “private limited company registration fees in India” isn’t one fixed number—it depends on your setup.

Step 6: ROC Scrutiny

The Registrar of Companies reviews your application. If anything’s unclear, you may get a query (a simple resubmission usually solves it).

Step 7: Certificate of Incorporation (COI), PAN & TAN

Once approved, you’ll receive the Certificate of Incorporation, plus PAN & TAN. Your company legally exists from this date.

Timeline & Cost

- Timeline for company registration in India:

5–10 working days, assuming name approval and documents are in order. - Cost:

- Government fees and stamp duty vary by state & authorized capital.

- Professional fees: depend on your consultant and scope (name checks, drafting MOA/AOA, re-submissions, etc.).

Pro tip: Clear documents + a strong name choice = fewer delays and less back-and-forth.

After Incorporation (don’t skip these)

- Open the current bank account (unless already handled via AGILE-PRO-S).

- Issue share certificates and maintain statutory registers.

- Appoint an auditor within 30 days.

- Apply for GST registration (if applicable).

- Set up accounting, payroll, TDS, and quarterly/annual MCA filings.

- Get your invoices, letterheads, and website updated with the new CIN.

Common mistakes to avoid

- Weak name search: Similar names or trademark conflicts invite rejection.

- Address proof too old: Keep documents within the last 2–3 months.

- Object clause mismatch: Your MOA should reflect your business activity.

- Rushing filings: A second pair of eyes saves days.

Pvt Ltd vs LLP

When choosing a business structure, it’s important to understand how a Private Limited Company differs from an LLP registration. Here’s a simple comparison:

| Factor | Private Limited Company | LLP |

| Ownership | Shares | Partnership interest |

| Funding | VC/PE friendly | Less common |

| Compliance | Higher | Moderate |

| ESOPs | Easy | Not typical |

If you want equity funding or ESOPs, a Pvt Ltd is generally better.

FAQs

1) How to do Private Limited Company Registration?

Complete Private Limited Company Registration in India via the MCA portal: get DSC, file SPICe+ Part A & B, submit e-MOA, e-AOA, and AGILE-PRO-S, pay fees, and receive COI, PAN, and TAN.

2) How long does Private Limited Company Registration online in India take?

Private limited company registration online in India usually takes 5–10 working days if the documents are correct and the company name is approved. Errors or missing documents cause delays.

3) What are the costs/fees for private limited company registration in India?

Fees include government charges, stamp duty, and professional fees. Optional services like GST or trademark filing are extra. The total cost depends on the state and authorized capital for Private Limited Company Registration Online in India.

4) Is minimum capital required for a private limited company registration in India?

No minimum paid-up capital is needed for Private Limited Company Registration in India. You can start with ₹1, making it simple for startups and small businesses.

5) Can a foreign national be a director in a private limited company registered in India?

Yes, foreign nationals can be directors, but at least one director must be an Indian resident for Private Limited Company Registration in India, as per MCA rules.

Port Land Management: Legal Framework for Major Ports, Land Use, and Coastal Development in India

Introduction

Port land management in India operates within a complex regulatory framework that balances developmental imperatives with environmental conservation and constitutional protections. The evolution from the Major Ports Trust Act, 1963 to the Major Port Authorities Act, 2021 [1] represents a fundamental shift in governance philosophy, moving from a trust-based model to a modern landlord port system aligned with global best practices. This transformation occurs against the backdrop of rigorous coastal regulation through the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Notification, 2019 [2], environmental protection mandates under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 [3], and land acquisition frameworks governed by contemporary legislation.

The legal architecture governing port land management reflects India’s strategic vision for becoming a global maritime hub while ensuring sustainable coastal development. With over 7,500 kilometers of coastline and twelve major ports handling approximately 60% of the country’s cargo traffic, the regulatory framework must address competing demands for port expansion, environmental protection, and community rights. The interplay between federal and state jurisdictions, combined with constitutional imperatives and international maritime obligations, creates a sophisticated legal matrix that requires careful navigation by port authorities, developers, and regulatory bodies.

Legislative Evolution and Current Framework

The Major Port Authorities Act, 2021

The Major Port Authorities Act, 2021, which came into force on November 3, 2021, fundamentally restructured the governance of India’s major ports [1]. Section 3 of the Act establishes the Board of Major Port Authority as the apex body for port administration, replacing the earlier trustee model with a corporate governance structure designed to enhance efficiency and transparency. The Act provides for “regulation, operation and planning of Major Ports in India and to vest the administration, control and management of such ports upon the Boards of Major Port Authorities” [1].

Chapter III of the Act, dealing with Management and Administration, contains crucial provisions for land management. Section 22 empowers the Board to acquire, hold, and dispose of property, including land, while Section 24 provides for planning and development activities. The Act introduces a landlord port model where the port authority functions as a landlord, leasing land and infrastructure to private operators while retaining ownership and regulatory control. This model facilitates private investment while maintaining public oversight of strategic assets.

The Act grants significant autonomy to port authorities in land use decisions within their notified limits. Section 25 empowers Boards to impose rates and charges for various services, including land use, while ensuring competitive pricing that promotes efficient port operations. The planning provisions under Section 24 require port authorities to prepare master plans that optimize land utilization while complying with environmental and safety regulations.

Constitutional and Land Acquisition Framework

Port development inevitably requires land acquisition, which operates under the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 [4]. For port projects, land acquisition must satisfy the public purpose test established under Article 300A of the Constitution, which provides that “no person shall be deprived of his property save by authority of law.” The Supreme Court’s recent judgment in Kolkata Municipal Corporation v. Bimal Kumar Shah [5] established seven constitutional tests for land acquisition, emphasizing procedural due process and fair compensation.

The Land Ports Authority of India Act, 2010 [6] provides a parallel framework for land border infrastructure, demonstrating the comprehensive approach to transport infrastructure development. Section 11 of this Act deems any land needed by the Authority as required for public purpose, streamlining acquisition processes while maintaining constitutional safeguards.

Port authorities must navigate the tension between development needs and property rights, particularly in coastal areas where land values are substantial and communities have traditional claims. The 2013 Act’s emphasis on rehabilitation and resettlement ensures that affected communities receive fair compensation and alternative livelihoods, particularly relevant for fishing communities displaced by port expansion.

Coastal Regulation and Environmental Framework

The Coastal Regulation Zone Notification, 2019

The CRZ Notification, 2019, issued under Section 3 of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, establishes a zoning system that significantly impacts port land management [2]. The notification divides coastal areas into four categories, each with specific development restrictions and permissions. CRZ-I areas, comprising ecologically sensitive zones like mangroves and coral reefs, impose the strictest limitations on development, permitting only essential infrastructure like “ports, harbours, jetties, wharves, quays, slipways, bridges, hover ports for coast guard, sea links” [2].

CRZ-II areas, covering urban areas developed up to the shoreline, allow port-related activities within municipal limits, providing flexibility for existing port cities to expand their maritime infrastructure. The notification’s provision that “NDZ shall not be applicable in such areas falling within notified Port limits” [2] creates important exemptions for established port areas, recognizing the operational necessities of port functions.

The 2019 notification introduced significant reforms benefiting port development. The reduction of No Development Zone (NDZ) requirements from 200 meters to 50 meters in CRZ-IIIA areas (densely populated rural areas) provides additional land for port-related activities. The streamlining of clearance procedures, with state-level authorities handling CRZ-II and CRZ-III clearances while the Ministry retains oversight for ecologically sensitive CRZ-I and marine CRZ-IV areas, expedites project approvals.

Environmental Protection Act Integration

Section 3 of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, empowers the Central Government to “take all such measures as it deems necessary or expedient for the purpose of protecting and improving the quality of the environment and preventing, controlling and abating environmental pollution” [3]. This broad mandate encompasses port development activities, requiring Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) for major projects and compliance with pollution control standards.

The Act’s Section 3(3) enables the constitution of specialized authorities for environmental protection [3], leading to the establishment of the National Coastal Zone Management Authority (NCZMA) and State Coastal Zone Management Authorities (SCZMA). These bodies possess delegated powers under Section 5 of the Act to issue directions for environmental protection in coastal areas, directly affecting port land use decisions.

Port authorities must obtain environmental clearances before commencing major development projects. However, the Supreme Court in National Highway Authority of India v. P.V. Krishnamoorthy [7] clarified that environmental clearance is not required for land acquisition notifications but must be obtained before actual construction begins. This distinction provides operational flexibility while maintaining environmental safeguards.

Land Use Planning and Development Control

Master Planning and Zoning

Port land management requires sophisticated planning frameworks that balance operational efficiency with regulatory compliance. The Major Port Authorities Act, 2021, mandates comprehensive master planning that integrates port operations with urban development and environmental protection. These plans must consider cargo projections, infrastructure requirements, environmental constraints, and community impacts.

The planning process involves multiple stakeholders including port authorities, state governments, urban development agencies, and environmental regulators. Port master plans must align with Coastal Zone Management Plans (CZMP) prepared under the CRZ Notification, ensuring consistency between port development and coastal conservation objectives. The integration of these planning frameworks prevents conflicts between developmental aspirations and environmental imperatives.

Land use within port areas follows functional zoning principles, segregating operational areas (berths, storage, handling), administrative zones, industrial areas for port-based industries, and buffer zones for environmental protection. This zoning approach optimizes land utilization while maintaining safety standards and environmental compliance.

Private Participation and Land Leasing

The landlord port model facilitates private investment through long-term land leasing arrangements. Port authorities retain land ownership while granting usage rights to private operators for specific terminals or facilities. These arrangements typically involve Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) or Build-Own-Operate-Transfer (BOOT) models that incentivize private investment while ensuring public asset protection.

Land lease agreements must comply with the Major Port Authorities Act’s provisions on competitive bidding and transparent allocation processes. The Tariff Authority for Major Ports (TAMP) regulates pricing structures, ensuring that land lease rates remain competitive while generating reasonable returns for port authorities. These regulatory mechanisms prevent arbitrary pricing and promote efficient land utilization.

The legal framework provides security of tenure for private investors while maintaining port authority oversight of land use. Lease agreements include performance standards, environmental compliance requirements, and provisions for lease termination in case of violations. This balanced approach encourages investment while protecting public interests.

Judicial Developments and Case Law

Supreme Court Jurisprudence on Land Acquisition

The Supreme Court’s evolving jurisprudence on land acquisition significantly impacts port development projects. The landmark judgment in Indore Development Authority v. Manoharlal [8] clarified that land acquisition proceedings do not lapse merely due to non-payment of compensation if the state takes physical possession of the land. This ruling provides certainty for port authorities undertaking large-scale land acquisition for expansion projects.

In A.V. Papayya Sastry v. Government of A.P. [9], the Court addressed port-specific land acquisition issues, recognizing the strategic importance of port development while emphasizing the need for fair compensation. The judgment established that Port Trust Authorities (now Port Authorities) possess the authority to initiate land acquisition proceedings under the Land Acquisition Act, 1894, for port development purposes.

The Court’s emphasis on procedural due process in land acquisition cases affects port development timelines. The seven constitutional tests established in Kolkata Municipal Corporation v. Bimal Kumar Shah [5] require port authorities to ensure proper notice, fair compensation assessment, and rehabilitation planning before acquiring private land. These requirements, while protecting individual rights, necessitate careful project planning and stakeholder consultation.

Environmental Law Enforcement

Judicial enforcement of environmental regulations has shaped port development practices. The Supreme Court’s intervention in cases involving CRZ violations has established strict accountability standards for port authorities. The demolition orders for unauthorized constructions in coastal areas, including the Maradu apartment complex case in Kerala, demonstrate the Court’s commitment to environmental protection.

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) has emerged as a crucial forum for environmental disputes related to port development. The Tribunal’s jurisdiction over Environment (Protection) Act violations includes CRZ non-compliance, requiring port authorities to maintain rigorous environmental monitoring and compliance systems. The NGT’s power to impose penalties and order remediation has strengthened environmental enforcement in the port sector.

Regulatory Compliance and Operational Challenges

Multi-Agency Coordination

Port land management involves coordination among multiple regulatory agencies with overlapping jurisdictions. Port authorities must navigate federal ministries (Ports, Environment, Defence), state governments, coastal zone management authorities, pollution control boards, and local municipal bodies. This complex regulatory landscape requires sophisticated compliance management systems and stakeholder engagement strategies.

The challenge intensifies in cases involving sensitive areas like defence installations, where clearances from the Ministry of Defence become mandatory. The Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB) guidelines require additional clearances for port developments near nuclear facilities, adding another layer of regulatory complexity.

Effective coordination mechanisms include joint clearance committees, single-window clearance systems, and integrated project monitoring frameworks. The government’s emphasis on ease of doing business has led to initiatives for streamlining approvals, though implementation remains challenging given the legitimate concerns of different regulatory agencies.

Enforcement Mechanisms and Penalties

The regulatory framework provides robust enforcement mechanisms for violations of land use and environmental norms. The Environment (Protection) Act prescribes penalties including imprisonment up to five years and fines up to Rs. 1 lakh for violations [3]. The CRZ Notification provides for prosecution of unauthorized activities in regulated zones, with additional powers for demolition of illegal structures.

Port authorities face potential liability for violations by their lessees or contractors. The principle of vicarious liability applies where port authorities fail to exercise adequate oversight of land use by private operators. This creates incentives for rigorous monitoring and compliance enforcement within port areas.

The enforcement framework includes administrative penalties, criminal prosecution, and civil remedies. Environmental compensation principles, as developed by the NGT, require violators to pay for ecological restoration and community compensation. These multifaceted enforcement mechanisms ensure serious consequences for non-compliance.

Future Directions and Policy Implications

Sustainable Development Integration

The evolving legal framework increasingly emphasizes sustainable development principles that balance economic growth with environmental protection and social equity. The Major Port Authorities Act’s emphasis on planning and the CRZ Notification’s scientific approach to coastal management reflect this integration. Future developments likely involve stronger environmental performance standards and enhanced community participation in port planning.