Introduction

Whenever a Job notification is out the first thing we do is go to the salary section and check what is the remuneration for that particular job. In order to apply for that particular job and later put all the effort and hard-work to get selected, is a long and tiring process. If our efforts are not compensated satisfactorily, we might not really like to get into the long time consuming process.

When we go through the salary section we often see words like Pay Scale, Grade Pay, or even level one or two salary and it is common to get confused between these jargons and to know the perfect amount of salary that we are going to receive.

To understand what pay scale, grade pay, various numbers of levels and other technical terms, we first need to know what pay commission is and how it functions.

Pay Commission

The Constitution of India under Article 309 empowers the Parliament and State Government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or any State.

The Pay Commission was established by the Indian government to make recommendations regarding the compensation of central government employees. Since India gained its independence, seven pay commissions have been established to examine and suggest changes to the pay structures of all civil and military employees of the Indian government.

The main objective of these various Pay Commissions was to improve the pay structure of its employees so that they can attract better talent to public service. In this 21st century, the global economy has undergone a vast change and it has seriously impacted the living conditions of the salaried class. The economic value of the salaries paid to them earlier has diminished. The economy has become more and more consumerized. Therefore, to keep the salary structure of the employees viable, it has become necessary to improve the pay structure of their employees so that better, more competent and talented people could be attracted to governance.

In this background, the Seventh Central Pay Commission was constituted and the government framed certain Terms of Reference for this Commission. The salient features of the terms are to examine and review the existing pay structure and to recommend changes in the pay, allowances and other facilities as are desirable and feasible for civil employees as well as for the Defence Forces, having due regard to the historical and traditional parities.

The Ministry of finance vide notification dated 25th July 2016 issued rules for 7th pay commission. The rules include a Schedule which shows categorically what payment has to be made to different positions. The said schedule is called 7th pay matrix

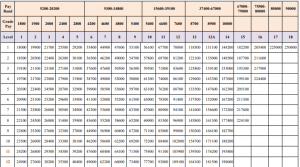

For the reference the table(7th pay matrix) is attached below.

Pay Band & Grade Pay

According to the table given above the first column shows the Pay band.

Pay Band is a pay scale according to the pay grades. It is a part of the salary process as it is used to rank different jobs by education, responsibility, location, and other multiple factors. The pay band structure is based on multiple factors and assigned pay grades should correlate with the salary range for the position with a minimum and maximum. Pay Band is used to define the compensation range for certain job profiles.

Here, Pay band is a part of an organized salary compensation plan, program or system. The Central and State Government has defined jobs, pay bands are used to distinguish the level of compensation given to certain ranges of jobs to have fewer levels of pay, alternative career tracks other than management, and barriers to hierarchy to motivate unconventional career moves. For example, entry-level positions might include security guard or karkoon. Those jobs and those of similar levels of responsibility might all be included in a named or numbered pay band that prescribed a range of pay.

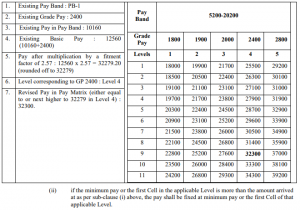

The detailed calculation process of salary according to the pay matrix table is given under Rule 7 of the Central Civil Services (Revised Pay) Rules, 2016.

As per Rule 7A(i), the pay in the applicable Level in the Pay Matrix shall be the pay obtained by multiplying the existing basic pay by a factor of 2.57, rounded off to the nearest rupee and the figure so arrived at will be located in that Level in the Pay Matrix and if such an identical figure corresponds to any Cell in the applicable Level of the Pay Matrix, the same shall be the pay, and if no such Cell is available in the applicable Level, the pay shall be fixed at the immediate next higher Cell in that applicable Level of the Pay Matrix.

The detailed table as mentioned in the Rules showing the calculation:

For example if your pay in Pay Band is 5200 (initial pay in pay band) and Grade Pay of 1800 then 5200+1800= 7000, now the said amount of 7000 would be multiplied to 2.57 as mentioned in the Rules. 7000 x 2.57= 17,990 so as per the rules the nearest amount the figure shall be fixed as pay level. Which in this case would be 18000/-.

The basic pay would increase as your experience at that job would increase as specified in vertical cells. For example if you continue to serve in the Basic Pay of 18000/- for 4 years then your basic pay would be 19700/- as mentioned in the table.

Dearness Allowance

However, the basic pay mentioned in the table is not the only amount of remuneration an employee receives. There are catena of benefits and further additions in the salary such as dearness allowance, HRA, TADA.

According to the Notification No. 1/1/2023-E.II(B) from the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure, the Dearness Allowance payable to Central Government employees was enhanced from rate of 38% to 42% of Basic pay with effect from 1st January 2023.

Here, DA would be calculated on the basic salary. For example if your basic salary is of 18,000/- then 42% DA would be of 7,560/-

House Rent Allowance

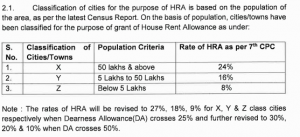

Apart from that the HRA (House Rent Allowance) is also provided to employees according to their place of duties. Currently cities are classified into three categories as ‘X’ ‘Y’ ‘Z’ on the basis of the population.

According to the Compendium released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in Notification No. 2/4/2022-E.II B, the classification of cities and rates of HRA as per 7th CPC was introduced.

See the table for reference

However, after enhancement of DA from 38% to 42% the HRA would be revised to 27%, 18%, and 9% respectively.

As above calculated the DA on Basic Salary, in the same manner HRA would also be calculated on the Basic Salary. Now considering that the duty of an employee’s Job is at ‘X’ category of city then HRA will be calculated at 27% of basic salary.

Here, continuing with the same example of calculation with a basic salary of 18000/-, the amount of HRA would be 4,840/-

Transport Allowance

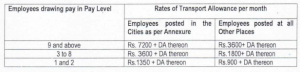

After calculation of DA and HRA, Central government employees are also provided with Transport Allowance (TA). After the 7th CPC the revised rates of Transport Allowance were released by the Ministry of Finance and Department of Expenditure in the Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B) wherein, a table giving detailed rates were produced.

The same table is reproduced hereinafter.

As mentioned above in the table, all the employees are given Transport Allowance according to their pay level and place of their duties. The list of annexed cities are given in the same Notification No. 21/5/2017-EII(B).

Again, continuing with the same example of calculation with a Basic Salary of 18000/- and assuming place of duty at the city mentioned in the annexure, the rate of Transport Allowance would be 1350/-

Apart from that, DA on TA is also provided as per the ongoing rate of DA. For example, if TA is 1350/- and rate of current DA on basic Salary is 42% then 42% of TA would be added to the calculation of gross salary. Here, DA on TA would be 567/-.

Calculation of Gross Salary

After calculating all the above benefits the Gross Salary is calculated.

Here, after calculating Basic Salary+DA+HRA+TA the gross salary would be 32,317/-

However, the Gross Salary is subject to few deductions such as NPS, Professional Tax, Medical as subject to the rules and directions by the Central Government. After the deductions from the Gross Salary an employee gets the Net Salary on hand.

However, it is pertinent to note that benefits such as HRA and TA are not absolute, these allowances are only admissible if an employee is not provided with a residence by the Central Government or facility of government transport.

Conclusion

Government service is not a contract. It is a status. The employees expect fair treatment from the government. The States should play a role model for the services. The Apex Court in the case of Bhupendra Nath Hazarika and another vs. State of Assam and others (reported in 2013(2)Sec 516) has observed as follows:

“………It should always be borne in mind that legitimate aspirations of the employees are not guillotined and a situation is not created where hopes end in despair. Hope for everyone is gloriously precious and that a model employer should not convert it to be deceitful and treacherous by playing a game of chess with their seniority. A sense of calm sensibility and concerned sincerity should be reflected in every step. An atmosphere of trust has to prevail and when the employees are absolutely sure that their trust shall not be betrayed and they shall be treated with dignified fairness then only the concept of good governance can be concretized. We say no more.”

The consideration while framing Rules and Laws on payment of wages, it should be ensured that employees do not suffer economic hardship so that they can deliver and render the best possible service to the country and make the governance vibrant and effective.

Written by Husain Trivedi Advocate

Airport Land Governance: AAI Act, Land Acquisition, Leasing, and Commercial Development

Abstract

Airport land governance in India operates through a complex regulatory framework encompassing the Airports Authority of India Act, 1994, land acquisition laws, leasing mechanisms, and commercial development regulations. This article examines the legal architecture governing airport land use, acquisition procedures, commercial leasing arrangements, and regulatory oversight mechanisms that shape India’s aviation infrastructure development.

Introduction

The governance of airport land in India represents a critical intersection of aviation law, property rights, and regulatory oversight. With India emerging as the world’s third-largest aviation market, the legal framework governing airport land has evolved to address complex issues surrounding acquisition, development, leasing, and commercial utilization. The regulatory landscape encompasses multiple statutes, regulatory authorities, and judicial precedents that collectively determine how airport land is acquired, managed, and commercially exploited.

The fundamental legal architecture rests upon three primary pillars: the constitutional framework for property rights, statutory provisions governing airport establishment and operation, and specialized regulations addressing commercial development. This framework has undergone significant evolution, particularly following the enactment of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, which replaced the colonial-era Land Acquisition Act, 1894.

Legal Framework Governing Airport Land

Constitutional Foundation

The constitutional foundation for airport land governance stems from Article 300A of the Constitution of India, which provides that “no person shall be deprived of his property save by authority of law.” [1] This fundamental principle establishes the legal requirement for due process in land acquisition, ensuring that any deprivation of property rights must follow established legal procedures and provide adequate compensation.

The Supreme Court has consistently interpreted Article 300A as requiring not merely compensation but also adherence to procedural safeguards. In a landmark ruling concerning land acquisition procedures, the Court established seven constitutional tests that must be satisfied for any lawful acquisition, emphasizing the right to notice, the right to be heard, and the right to fair compensation. [2]

The Airports Authority of India Act, 1994

The Airports Authority of India Act, 1994 (AAI Act) constitutes the primary legislation governing airport development and management in India. Section 19 of the AAI Act provides the statutory foundation for land acquisition, stating that “any land required by the Authority for the discharge of its functions under this Act shall be deemed to be needed for a public purpose and such land may be acquired for the Authority under the provisions of the Land Acquisition Act, 1894 or of any other corresponding law for the time being in force.” [3]

This provision establishes a presumption of public purpose for airport-related land acquisition, thereby streamlining the acquisition process. However, this presumption does not exempt airport authorities from complying with procedural requirements under applicable land acquisition laws. The AAI Act also empowers the Authority to establish airports and assist in private airport development through Section 12(3)(aa), which permits the Authority to “establish airports, or assist in the establishment of private airports, by rendering such technical, financial or other assistance which the Central Government may consider necessary for such purpose.”

The 2003 amendments to the AAI Act introduced significant provisions regarding private airports and leasing arrangements. Section 12A, inserted by the 2003 Amendment Act, enables the Authority to lease airport premises for better management, subject to Central Government approval. This provision states: “the Authority may, in the public interest or in the interest of better management of airports, make a lease of the premises of an airport (including buildings and structures thereon and appertaining thereto) to carry out some of its functions under section 12.”

Land Acquisition Framework

Evolution from the 1894 Act to the 2013 LARR Act

The transition from the Land Acquisition Act, 1894 to the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 (LARR Act) represents a paradigmatic shift in India’s approach to land acquisition. The 2013 Act introduced enhanced procedural safeguards, increased compensation mechanisms, and mandatory rehabilitation provisions.

Under the LARR Act, airport development falls within the definition of “infrastructure projects” for which land acquisition is permitted. However, the Act introduces stringent procedural requirements including Social Impact Assessment (SIA), mandatory consent provisions, and enhanced compensation formulas. For airport projects, the consent of at least 70% of affected families is required for public purpose acquisitions, while 80% consent is mandated for public-private partnership projects. [4]

The compensation structure under the LARR Act provides for payment of four times the market value for rural land and twice the market value for urban land. Additionally, the Act mandates rehabilitation and resettlement provisions for affected families, marking a significant departure from the compensation-only approach of the 1894 Act.

Procedural Requirements and Safeguards

The LARR Act establishes a comprehensive procedural framework beginning with preliminary notification under Section 11, followed by Social Impact Assessment under Section 4, and public hearing requirements under Section 5. The process culminates in a final declaration under Section 19, subject to approval by the appropriate government.

For airport projects, these procedures must be scrupulously followed, as demonstrated in recent judicial pronouncements. The Bombay High Court’s decision regarding Navi Mumbai International Airport land acquisition illustrates the consequences of procedural non-compliance. The Court quashed the Section 6 declaration, finding that authorities failed to justify invoking urgency provisions and denied affected landowners their statutory right to be heard under Section 5A. [5]

Commercial Development and Leasing Regulations

Regulatory Framework for Commercial Activities

Airport commercial development operates within a dual regulatory framework encompassing both aviation-specific regulations and general commercial law. The primary regulatory authority for commercial activities at airports is the Airports Economic Regulatory Authority of India (AERA), established under the Airports Economic Regulatory Authority of India Act, 2008.

AERA regulates tariffs and charges for aeronautical services at major airports, defined as airports handling more than 3.5 million passengers annually. The Authority’s jurisdiction extends to development fees, passenger service fees, and charges related to aeronautical services. However, AERA’s regulatory scope is limited to aeronautical services, with non-aeronautical commercial activities governed by general commercial law and AAI regulations.

The amendment to the AERA Act in 2019 raised the threshold for “major airports” from 1.5 million to 3.5 million passengers annually, thereby reducing the number of airports under direct AERA regulation from 32 to approximately 16. This change reflects the government’s intent to balance regulatory oversight with operational flexibility for smaller airports.

Leasing Mechanisms and Commercial Exploitation

Section 12A of the AAI Act provides the statutory foundation for airport leasing arrangements. This provision enables the Authority to lease airport premises to private operators, subject to Central Government approval. The lease must serve either public interest or better airport management, and cannot affect the Authority’s core functions relating to air traffic services and security.

Commercial leasing at airports encompasses various activities including retail outlets, food and beverage services, parking facilities, cargo handling, and ground support services. The AAI has developed standardized leasing policies that govern rental rates, escalation clauses, and operational requirements. Current lease rental rates are subject to periodic revision, with the Authority implementing a structured escalation mechanism. [6]

The commercial exploitation of airport land has become increasingly important for financial sustainability. Non-aeronautical revenue, which includes commercial leasing income, has grown from 10-15% of total AAI revenue in the early 1990s to 20-30% currently, though this remains significantly below international benchmarks where major airport operators derive 60-70% of revenue from non-aeronautical sources.

Public-Private Partnership Models

The AAI Act facilitates various public-private partnership models for airport development and operation. Section 12(3)(n) empowers the Authority to “form one or more companies under the Companies Act, 1956 or under any other law relating to companies to further the efficient discharge of the functions imposed on it by this Act.”

Several major Indian airports operate under PPP models, including Delhi International Airport Limited (DIAL), Mumbai International Airport Limited (MIAL), and Bangalore International Airport Limited (BIAL). These arrangements typically involve long-term concession agreements spanning 30-60 years, with private partners responsible for development, operation, and maintenance while AAI retains ownership of the underlying land.

Regulatory Oversight and Compliance

AERA’s Role in Tariff Regulation

The Airports Economic Regulatory Authority exercises regulatory oversight over tariff determination and service quality standards at major airports. AERA’s regulatory approach employs a multi-stage assessment process examining materiality, competition, and reasonableness of existing arrangements.

For tariff determination, AERA follows a regulatory building blocks approach, calculating fair rate of return based on weighted average cost of capital. The Authority has faced judicial scrutiny regarding its methodology, with the Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal (TDSAT) examining AERA’s discretionary powers in determining cost of equity. [7]

AERA’s regulatory framework distinguishes between aeronautical and non-aeronautical services, with direct regulation primarily focused on aeronautical services. Non-aeronautical services, including most commercial leasing activities, are subject to lighter regulatory oversight, allowing market forces to determine pricing and terms.

Environmental and Planning Regulations

Airport land development must comply with environmental clearance requirements under the Environment Protection Act, 1986 and associated rules. Major airport projects require Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and clearance from the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change.

The Aircraft Rules, 1937 establish technical requirements for aerodrome licensing, including specifications for runway dimensions, safety areas, and obstacle limitations. These regulations directly impact permissible land use within airport boundaries and surrounding areas, creating height restrictions and land use constraints that affect commercial development potential.

Case Law Analysis and Judicial Precedents

Supreme Court Jurisprudence on Airport Land Acquisition

The Supreme Court has established important precedents regarding airport land acquisition, particularly concerning the interpretation of “public purpose” and procedural requirements. In a 2007 judgment, the Court held that airport expansion and development constitute valid public purposes, noting that “the words used in the Notification, namely ‘the planned development of Delhi’ are wide enough to include the expansion and development of the airport. That is also a ‘public purpose’.” [8]

The Court’s jurisprudence emphasizes strict adherence to statutory procedures, regardless of the public benefit derived from airport development. Recent pronouncements have reinforced the principle that procedural compliance cannot be waived on grounds of public interest, establishing that land acquisition authorities must demonstrate clear justification for invoking urgency provisions.

Land Acquisition Compensation Disputes

Judicial decisions regarding compensation for airport land acquisition have established important precedents for valuation methodologies. Courts have consistently held that compensation must reflect market value at the time of acquisition, with appropriate consideration for development potential and locational advantages.

The Bombay High Court’s recent decision in airport land acquisition cases has emphasized the importance of comparable sales evidence and expert valuation in determining fair compensation. The Court rejected attempts to limit compensation based on purported restrictions on land use, holding that industrial development potential and airport proximity are legitimate factors for consideration in valuation. [9]

Challenges and Emerging Issues

Balancing Development Needs with Property Rights

The tension between infrastructure development imperatives and individual property rights remains a central challenge in airport land governance. While airport development serves broader public interests, the process often involves displacement of agricultural communities and disruption of traditional livelihoods.

The LARR Act’s emphasis on rehabilitation and resettlement represents an attempt to address these concerns, but implementation challenges persist. Social Impact Assessments frequently reveal significant adverse impacts on affected communities, requiring careful balancing of development benefits against social costs.

Commercial Viability and Financial Sustainability

Airport authorities face increasing pressure to enhance commercial revenue generation while maintaining operational efficiency and service quality. The regulatory framework must evolve to facilitate innovative commercial arrangements while ensuring that core aeronautical functions are not compromised.

The challenge is particularly acute for smaller airports where passenger traffic may not support extensive commercial development. Regulatory policies must provide sufficient flexibility to enable viable commercial models while maintaining appropriate oversight.

Technological Evolution and Land Use Efficiency

Advancing aviation technology and changing passenger expectations require continuous adaptation of airport facilities and land use patterns. The regulatory framework must accommodate emerging requirements such as cargo hubs, maintenance facilities, and integrated transport connectivity.

Regulatory authorities must balance the need for operational flexibility with requirements for environmental protection and community welfare. This involves developing adaptive regulatory approaches that can respond to technological change while maintaining essential safeguards.

Future Directions and Recommendations

Regulatory Reform Initiatives

The government has initiated several regulatory reforms aimed at streamlining airport development while strengthening procedural safeguards. The proposed amendments to the AAI Act seek to enhance operational flexibility while maintaining regulatory oversight.

Key reform priorities include simplification of land acquisition procedures for airport development, enhancement of commercial revenue opportunities, and strengthening of environmental and social safeguards. These reforms must balance competing objectives while ensuring compliance with constitutional requirements and international best practices.

Institutional Capacity Building

Effective implementation of the airport land governance framework requires enhanced institutional capacity across regulatory agencies, airport authorities, and judicial institutions. This includes technical expertise in valuation methodologies, environmental assessment, and regulatory economics.

Training programs for regulatory personnel and standardization of procedures across different authorities can improve consistency and efficiency in decision-making. Regular review and updating of regulatory guidelines ensures that the framework remains responsive to emerging challenges and opportunities.

Conclusion

Airport land governance in India operates within a complex legal framework that balances infrastructure development needs with property rights protection and commercial viability requirements. The evolution from the colonial-era land acquisition system to the current rights-based approach reflects broader constitutional and policy commitments to procedural fairness and just compensation.

The regulatory framework continues to evolve in response to changing aviation industry requirements, technological advancement, and judicial interpretation. Success in achieving efficient airport development while protecting individual rights depends on careful implementation of existing legal provisions and continued adaptation to emerging challenges.

The future of airport land governance will likely involve further integration of environmental, social, and economic considerations within a unified regulatory framework. This requires continued dialogue between regulatory authorities, industry stakeholders, and affected communities to ensure that airport development serves broader public interests while respecting individual rights and community welfare.

Effective airport land governance ultimately depends on the quality of institutional arrangements, the clarity of legal frameworks, and the commitment of all stakeholders to balanced and sustainable development. As India’s aviation sector continues to expand, the importance of robust and fair land governance mechanisms will only increase, requiring continued attention to legal reform, institutional capacity building, and stakeholder engagement.

References

[1] Constitution of India, Article 300A.

[3] Airports Authority of India Act, 1994, Section 19. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1979/1/AAairpoert1994__55.pdf

[5] Bombay High Court. Navi Mumbai Airport Land Acquisition Case. Available at: https://www.constructionworld.in/transport-infrastructure/aviation-and-airport-infra/bombay-hc-quashes-navi-mumbai-airport-land-acquisition-as-illegal/70111

[6] Airports Authority of India. Current Rates – Land Lease Rental. Available at: https://www.aai.aero/en/business-opportunities/current-rates

[7] Rules of Statutory Interpretation and the Airport Economic Regulatory Authority. Available at: https://www.mondaq.com/india/aviation/1406522/rules-of-statutory-interpretation-and-the-airport-economic-regulatory-authority

[8] Supreme Court of India. Delhi Airport Land Acquisition Case (2007) 5 SCC 231. Available at: https://www.aironline.in/legal-judgements/(2007)+3+CTC+574+(SC)

[9] Bombay High Court. Mumbai Airport Land Acquisition Reference Case. Available at: https://www.lawtext.in/judgement.php?bid=1295

LARR Act 2013: Sector-wise Implementation and Special Provisions in India

Introduction

The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 (LARR Act) [1] represents a paradigmatic shift in India’s approach to land acquisition, replacing the colonial-era Land Acquisition Act of 1894. This legislation embodies a human rights-based approach to development, ensuring that affected families become partners in development rather than victims of displacement. The Act’s sector-specific applications and special provisions demonstrate the legislature’s recognition that different types of projects require nuanced regulatory frameworks while maintaining the core principles of fair compensation, transparency, and rehabilitation.

Legislative Framework and Constitutional Basis

The LARR Act 2013 derives its constitutional authority from Article 300-A of the Constitution, which provides that “no person shall be deprived of his property save by authority of law” [2]. The Supreme Court has consistently held that while the right to property ceased to be a fundamental right after the 44th Amendment in 1978, it remains a constitutional and human right requiring scrupulous adherence to legal procedures [3].

Section 2 of the LARR Act 2013 delineates the scope of application, establishing two distinct categories of land acquisition. Subsection (1) applies when the government acquires land for its own use, including Public Sector Undertakings and public purposes. Subsection (2) extends the Act’s provisions to acquisitions for public-private partnerships and private companies, with mandatory consent requirements of 70% and 80% respectively [4].

Sector-wise Implementation Framework

Infrastructure Projects and Linear Developments

The LARR Act 2013 Act provides comprehensive coverage for infrastructure projects under Section 2(1)(b), which encompasses all activities listed in the Government of India’s Infrastructure Notification of March 27, 2012 [5]. This includes railways, highways, power lines, irrigation canals, and telecommunications infrastructure. The special significance of linear infrastructure projects is recognized through specific exemptions under Section 10(4), which excludes linear projects from the restrictions on acquisition of irrigated multi-cropped land [6].

For railways specifically, the Act maintains the existing framework under the Railways Act, 1989, which is listed in the Fourth Schedule as an exempted legislation. However, the compensation, rehabilitation, and resettlement provisions must be harmonized with the LARR Act within the prescribed timeframe. The Supreme Court’s interpretation in various cases has clarified that while procedural provisions of specific acts remain applicable, compensation standards must align with the enhanced provisions of the LARR Act.

Defence and National Security Projects

Section 2(1)(a) accords special status to acquisitions for “strategic purposes relating to naval, military, air force, and armed forces of the Union, including central paramilitary forces or any work vital to national security or defence of India or State police, safety of the people” [7]. This provision recognizes the sovereign imperative of national security while ensuring that even defence-related acquisitions are subject to fair compensation principles.

The urgency provisions under Section 40 permit expedited acquisition for defence purposes, allowing the Collector to take possession within thirty days of publication of notice under Section 21. However, the Act mandates payment of 80% of estimated compensation before taking possession and provides for additional compensation of 75% of the total compensation amount, except where the project affects sovereignty and integrity of India [8].

Mining and Mineral Development

Mining activities fall under the infrastructure category as specified in Section 2(1)(b)(iii), which includes “project for industrial corridors or mining activities” [9]. The Act’s application to mining represents a significant departure from earlier regimes, bringing mining operations under the comprehensive rehabilitation and resettlement framework.

The Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition and Development) Act, 1957, and the Land Acquisition (Mines) Act, 1885, are included in the Fourth Schedule, indicating that specific mining legislation continues to govern procedural aspects while compensation provisions must align with the LARR Act [10]. This dual framework ensures specialized treatment for mining operations while guaranteeing enhanced compensation to affected communities.

Atomic Energy and Special Economic Zones

The Atomic Energy Act, 1962, occupies a unique position in the LARR framework, being specifically exempted under Section 105 and listed in the Fourth Schedule. This exemption acknowledges the specialized nature of atomic energy projects and the need for maintaining the existing statutory framework under the Department of Atomic Energy [11]. Similarly, the Special Economic Zones Act, 2005, maintains its distinct procedural framework while ensuring that compensation standards remain consistent with the LARR Act.

Industrial Corridors and Manufacturing Zones

Section 2(1)(b)(iii) specifically addresses “project for industrial corridors or mining activities, national investment and manufacturing zones, as designated in the National Manufacturing Policy” [12]. This provision reflects the government’s focus on developing industrial infrastructure while ensuring that such development does not compromise the rights of affected communities.

State governments have utilized their legislative powers under Article 254(2) to create specialized frameworks for industrial projects. The Andhra Pradesh Land Acquisition Laws (Revival of Operation, Amendment, and Validation) Act, 2019, exemplifies this approach, though its constitutional validity was upheld by the Supreme Court [13].

Special Provisions and Exemptions

Scheduled Areas and Tribal Rights

Chapter VI of the LARR Act 2013 contains detailed provisions for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, recognizing their special vulnerability to displacement. Section 41 mandates that “as far as possible, no acquisition of land shall be made in the Scheduled Areas” and requires prior consent of Gram Sabha or Panchayats in all cases of acquisition in Scheduled Areas [14].

The Act requires preparation of a Development Plan for projects involving displacement of Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes, including procedures for settling land rights and restoring titles. Section 42 ensures continuity of reservation benefits and statutory safeguards in resettlement areas, regardless of whether the resettlement area falls within Scheduled Areas [15].

Social Impact Assessment and Environmental Safeguards

The mandatory Social Impact Assessment under Section 4 represents a fundamental innovation in land acquisition law. The assessment must evaluate whether the proposed acquisition serves public purpose, estimate affected families, assess the extent of displacement, and determine if the proposed land area is the absolute minimum required [16].

Section 6 provides for simultaneous Environmental Impact Assessment, ensuring comprehensive evaluation of project impacts. However, for irrigation projects where Environmental Impact Assessment is mandatory under other laws, the Social Impact Assessment provisions do not apply [17].

Food Security Safeguards

Section 10 establishes comprehensive safeguards for food security, prohibiting acquisition of irrigated multi-cropped land except under exceptional circumstances as demonstrable last resort. The Act requires that aggregate acquisition of such land for all projects in a district or state shall not exceed limits notified by the appropriate government [18].

The provision for developing equivalent culturable wasteland or depositing equivalent value for agricultural enhancement demonstrates the legislature’s commitment to maintaining agricultural productivity while permitting necessary development.

Judicial Interpretation and Case Law

Section 24 and Transitional Provisions

The Supreme Court’s Constitution Bench judgment in Indore Development Authority v. Manoharlal (2020) 8 SCC 129 settled the interpretation of Section 24, which governs the transition from the 1894 Act to the 2013 Act [19]. The Court clarified that land acquisition proceedings under the 1894 Act are deemed to have lapsed if an award was made five years or more prior to the commencement of the 2013 Act, but physical possession was not taken and compensation was not paid.

The judgment overruled the earlier decision in Pune Municipal Corporation v. Harakchand Misrimal Solanki (2014) 3 SCC 183, holding that compensation is considered “paid” even if deposited in government treasury, not necessarily requiring court deposit [20]. This interpretation significantly impacts the number of lapsed acquisitions and the subsequent application of enhanced compensation under the 2013 Act.

Consent Requirements and Public Purpose

The Supreme Court has consistently upheld the consent requirements for private company acquisitions, recognizing them as essential safeguards against arbitrary acquisition. The Court’s approach to interpreting “public purpose” has evolved to ensure that private benefit does not masquerade as public purpose, particularly in the context of acquisitions for subsequent transfer to private entities [21].

Compensation Mechanisms and Rehabilitation Framework

Enhanced Compensation Structure

The Act establishes a comprehensive compensation framework under Sections 26-30, requiring market value determination based on stamp duty values, average sale prices, or consented amounts, whichever is higher. The compensation is then multiplied by factors specified in the First Schedule – four times market value for rural areas and twice for urban areas [22].

Additionally, Section 30 mandates solatium equivalent to 100% of compensation amount, and Section 69 provides for 12% annual interest from the date of notification until award or possession, whichever is earlier [23].

Rehabilitation and Resettlement Entitlements

The Second Schedule provides detailed rehabilitation and resettlement entitlements, including employment for one member of each affected family, residential plots, transportation allowance, and various monetary benefits. The Third Schedule mandates provision of infrastructural amenities in resettlement areas, ensuring that displaced communities have access to basic services [24].

State Amendments and Regional Variations

Several states have enacted amendments to address local requirements while maintaining the Act’s core principles. The Maharashtra Act 37 of 2018 and Andhra Pradesh Act 22 of 2018 introduce provisions for lump sum payments in lieu of detailed rehabilitation and resettlement for certain categories of projects [25].

These amendments demonstrate the federal structure’s flexibility in allowing states to adapt the central framework to local conditions while ensuring that fundamental rights of affected persons are not compromised.

Contemporary Challenges and Future Directions

The implementation of the LARR Act 2013 aces several challenges, including delays in Social Impact Assessment completion, consent procurement difficulties, and inadequate rehabilitation infrastructure. The recent Supreme Court observations in various cases indicate the need for balancing development imperatives with individual rights protection.

The Act’s emphasis on making affected persons “partners in development” through enhanced compensation and comprehensive rehabilitation represents a progressive approach that could serve as a model for other developing countries facing similar development-displacement dilemmas.

Conclusion

The LARR Act, 2013, through its sector-specific provisions and special safeguards, represents a comprehensive attempt to balance development needs with human rights protection. The Act’s recognition of different sectoral requirements while maintaining universal principles of fair compensation and rehabilitation demonstrates sophisticated legislative drafting adapted to India’s diverse development landscape.

The judicial interpretation of key provisions, particularly Section 24, has provided necessary clarity while highlighting the ongoing tension between development imperatives and individual rights. As India continues its infrastructure development trajectory, the LARR Act’s framework provides both the flexibility for sectoral adaptation and the rigidity necessary for rights protection.

The success of the Act ultimately depends on effective implementation, adequate budgetary allocation for rehabilitation, and continued judicial oversight to ensure that the legislative intent of making affected persons partners in development is realized in practice.

References

[1] The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, Act No. 30 of 2013. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2121

[2] Constitution of India, Article 300-A. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/constitution/

[3] Haryana State Industrial and Infrastructure Development Corporation v. Deepak Aggarwal, 2022 SCC OnLine SC 644

[4] The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, Section 2

[5] Government of India, Department of Economic Affairs Notification No. 13/6/2009-INF, dated March 27, 2012

[6] The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, Section 10(4)

[7] The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, Section 2(1)(a)

[8] The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, Section 40

[9] The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, Section 2(1)(b)(iii)

[10] The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, Fourth Schedule

Railway Land Administration: Acquisition, Leasing, Encroachment, and Commercial Use

Executive Summary

Railway land administration in India operates within a complex legal framework governing acquisition, leasing, encroachment management, and commercial utilization. The regulatory structure encompasses multiple statutes including The Railways Act, 1989, Land Acquisition Act, 1894, and recent policy initiatives under the PM Gati Shakti framework. This comprehensive analysis examines the legal mechanisms, procedural requirements, and judicial interpretations that shape railway land management practices in contemporary India.

Introduction

Indian Railways, being one of the world’s largest railway networks spanning over 67,000 kilometers, requires extensive land holdings for operational efficiency and infrastructure development [1]. The administration of railway land involves intricate legal processes that balance public interest in transportation infrastructure with private property rights and commercial opportunities. The legal framework has evolved significantly, particularly following the introduction of the PM Gati Shakti National Master Plan, which aims to integrate multimodal connectivity and enhance logistics efficiency [2].

Statutory Framework for Railway Land Acquisition

The Railways Act, 1989: Core Provisions

The Railways Act, 1989 serves as the primary legislation governing railway land acquisition through Chapter IVA, which incorporates sections 20A through 20O [3]. These provisions establish a comprehensive mechanism for acquiring land specifically for railway projects, distinct from general land acquisition procedures.

Section 20A of the Railways Act, 1989 empowers the Central Government to acquire land for special railway projects. The provision states: “Where the Central Government is satisfied that for a public purpose any land is required for execution of a special railway project, it may, by notification, declare its intention to acquire such land” [4]. This notification must provide a brief description of both the land and the special railway project for which acquisition is intended.

The procedural safeguards embedded within Section 20B authorize competent authorities to conduct inspections, surveys, measurements, valuations, and enquiries upon notification under Section 20A. Importantly, the statute mandates compensation for damages caused during preliminary activities such as surveying, digging, or boundary marking, with payment required within six months of work completion [5].

Objection and Hearing Procedures

Section 20D establishes crucial procedural rights for affected landowners, providing a thirty-day window from notification publication for submitting objections to land acquisition. The competent authority must consider these objections and provide reasoned decisions, ensuring due process compliance [6]. This provision gained significant judicial attention in the case of Nareshbhai Bhagubhai v. Union of India, where the Supreme Court emphasized that objections must be properly considered and disposed of after providing adequate hearing opportunities to affected parties [7].

Declaration and Vesting Process

Following objection disposal or expiry of the objection period, Section 20E mandates submission of a report to the Central Government, which then issues a declaration notification. Upon publication of this declaration, the land vests absolutely in the Central Government free from all encumbrances, subject to compensation payment as determined under Section 20F [8].

Compensation Mechanisms

The compensation framework under Section 20F encompasses multiple components: market value on the notification date, severance damages, consequential damages to other immovable property or earnings, and reasonable relocation expenses. Additionally, a mandatory sixty percent solatium is awarded over the market value, acknowledging the compulsory nature of acquisition [9].

Contemporary Land Leasing and Commercial Use Framework

PM Gati Shakti Land Policy Revolution

The Union Cabinet’s approval of the revised railway land policy in September 2022 marked a paradigmatic shift in railway land utilization [2]. The Policy for Management of Railway Land, issued through Railway Board’s Master Circular dated October 4, 2022, supersedes all previous guidelines and introduces market-oriented leasing mechanisms aligned with the PM Gati Shakti framework [10].

This policy transformation extends lease periods from five years to thirty-five years for cargo-related activities, while reducing annual lease charges from six percent to 1.5 percent of market value. The reform aims to attract private investment in cargo terminals and multimodal logistics infrastructure, potentially generating approximately 1.2 lakh employment opportunities [2].

Permitted Commercial Activities

The revised framework categorizes permitted activities into distinct classifications. Cargo terminals and related facilities receive preferential treatment with thirty-five-year lease terms at 1.5 percent annual charges with six percent escalation. Public utility infrastructure including electricity, gas, water supply, telecommunications, and urban transport systems qualify for similar terms under the integrated development mandate [10].

Social infrastructure development receives exceptional consideration, with hospitals established through public-private partnerships and Kendriya Vidyalaya schools permitted on sixty-year leases at nominal rates of one rupee per square meter annually. Renewable energy projects for exclusive railway use enjoy thirty-five-year terms at the same nominal rate [10].

Digital Processing and Approval Mechanisms

The Indian Railways Lease License Processing System (IR-LSPS) and Indian Railways Rail Bhoomi Crossing Seva (IR-RBCS) provide online platforms for application submission and approval processing. The policy mandates specific timeframes: fifteen days for small-diameter utility crossings, sixty days for other way-leave permissions, and ninety days for land lease approvals [10].

Encroachment Management and Legal Remedies

Jurisdictional Framework

Railway land encroachment presents complex legal challenges requiring coordination between railway authorities, local administration, and judicial oversight. The Public Premises (Eviction of Unauthorised Occupants) Act, 1971 provides statutory mechanisms for removing unauthorized occupants from public premises, including railway land [11].

Judicial Precedents and Enforcement Challenges

The Haldwani railway land encroachment case exemplifies the tension between property rights and public interest. The Uttarakhand High Court’s comprehensive order in December 2022 addressed unauthorized occupation of 78 acres of railway land by approximately 4,365 homes housing 50,000 residents [12]. The Supreme Court’s subsequent intervention requiring rehabilitation planning before eviction demonstrates judicial recognition of humanitarian considerations in encroachment removal.

The case analysis reveals that nazul land classifications and historical municipal arrangements complicate title determination. The High Court concluded that railway land vested through the 1959 notification remained railway property despite municipal management arrangements, invalidating subsequent transactions [12].

Regulatory Compliance and Enforcement

Railway authorities possess inherent powers to prevent and remove encroachments under various statutory provisions. However, enforcement must comply with constitutional due process requirements, including adequate notice, hearing opportunities, and consideration of rehabilitation needs for vulnerable populations [11].

Market Valuation and Financial Implications

Valuation Methodology

The current policy establishes market value determination based on prevalent circle rates, ready reckoner rates, or guidance values at lease agreement execution. For cargo terminals, industrial rates apply where specified by state authorities. The framework recognizes state-specific logistics industry incentives, requiring railways to provide equivalent discounts [10].

Revenue Generation and Economic Impact

The liberalized leasing policy projects substantial revenue enhancement through increased private participation in railway infrastructure development. The policy’s emphasis on competitive bidding for new cargo facilities while protecting existing operators through migration options balances market efficiency with stakeholder interests [2].

The integration of 300 PM Gati Shakti cargo terminals over five years represents significant infrastructure investment, potentially reducing national logistics costs and enhancing rail freight modal share [2].

Right of Way and Infrastructure Development

Crossing Permissions and Utility Integration

The policy framework accommodates various infrastructure requirements through differentiated charging structures. Underground utilities including optical fiber cables, water pipelines, and telecommunications infrastructure receive simplified approval processes with reduced fees, facilitating integrated development [10].

Metro and rapid rail transit systems receive special consideration with depth-based charging mechanisms. Underground structures exceeding thirty meters depth qualify for nominal fees of ten thousand rupees annually, encouraging deep infrastructure development that minimizes surface disruption [10].

Environmental and Safety Considerations

Railway land utilization must comply with environmental clearances and safety regulations. The thirty-meter restricted zone from railway tracks requires railway consent for construction activities, ensuring operational safety while permitting compatible development [6].

Dispute Resolution and Administrative Remedies

Internal Grievance Mechanisms

The policy establishes divisional-level dispute resolution through standing committees comprising three officers from engineering, finance, and user departments. Divisional Railway Managers exercise final authority over land allocation disputes, subject to judicial review [10].

Judicial Oversight and Constitutional Safeguards

Courts exercise supervisory jurisdiction over railway land administration decisions, particularly regarding acquisition procedures and compensation adequacy. The Supreme Court’s recognition of property rights as fundamental human rights in Vidya Devi v. State of Himachal Pradesh reinforces constitutional protection against arbitrary state action [13].

Future Directions and Policy Implications

Integration with National Infrastructure Planning

The PM Gati Shakti framework’s emphasis on multimodal connectivity requires continued coordination between railway land policy and broader infrastructure development initiatives. The online approval systems represent technological advancement in administrative efficiency while maintaining regulatory oversight [2].

Sustainable Development Considerations

Future policy development must balance commercial utilization with environmental sustainability and social equity. The framework’s provision for renewable energy projects and public utilities reflects growing emphasis on sustainable infrastructure development [10].

Conclusion

Railway land administration in India operates within a sophisticated legal framework that continues evolving to meet contemporary infrastructure demands while protecting stakeholder interests. The recent policy liberalization under PM Gati Shakti represents a significant advancement in regulatory modernization, potentially transforming railway land from a static asset to a dynamic platform for integrated infrastructure development.

The success of these reforms depends on effective implementation, stakeholder coordination, and continued judicial oversight ensuring constitutional compliance. In this context, railway land administration emphasizes transparency through online systems, competitive allocation mechanisms, and defined timeframes, establishing a foundation for efficient land utilization that serves broader national development objectives while respecting individual property rights and due process requirements.

References

[1] Indian Railways. (2024). Annual Statistical Statement 2023-24. Ministry of Railways, Government of India. Available at: https://indianrailways.gov.in/

[2] Press Information Bureau. (2022). Cabinet approves policy on long term leasing of Railways Land for implementing PM Gati Shakti framework. Press Release. Available at: https://www.pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1857411

[3] The Railways Act, 1989. Act No. 24 of 1989. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/1908

[4] Section 20A, The Railways Act, 1989. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/101714962/

[5] The Railways Act, 1989, Chapter IVA. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1022405/

[6] Legal Service India. (2024). Acquisition of land under the Indian Railways Act 1989. Available at: https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-5079-acquisition-of-land-under-the-indian-railways-act-1989.html

[7] Nareshbhai Bhagubhai v. Union of India, Supreme Court of India, August 13, 2019. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/25628246/

[8] Government Staff. (2022). Policy for Management of Railway Land – Railway Board’s Master Circular dated 04.10.2022. Available at: https://www.govtstaff.com/2022/10/policy-for-management-of-railway-land-railway-boards-master-circular.html

[9] Union of India v. Ramchandra, Supreme Court of India, August 11, 2022. Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/65735726/

[10] Railway Board. (2022). Master Circular on Policy for Management of Railway Land. Circular No. 2021/LML/25/5, dated October 4, 2022.

NHAI Land Acquisition and Management: Legal Framework, Challenges, and Future Directions

Introduction

The National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) stands as the cornerstone of India’s highway infrastructure development, tasked with the monumental responsibility of managing over 150,000 kilometers of national highways across the country [1]. Established under the National Highways Authority of India Act, 1988, NHAI operates as an autonomous body under the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH), wielding significant powers in land acquisition, highway maintenance, right-of-way management, and infrastructure development [2]. The complexity of NHAI’s land management operations encompasses a intricate web of legal frameworks, regulatory compliance, and operational challenges that demand comprehensive understanding of both statutory provisions and judicial interpretations.

The legal foundation for NHAI’s land management activities rests primarily on two pivotal legislations: the National Highways Act, 1956, and the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 (RFCTLARR Act) [3]. These statutory frameworks create a unique paradigm where traditional land acquisition procedures are modified to accommodate the specific requirements of highway development, while ensuring fair compensation and rehabilitation for affected landowners.

Legal Framework Governing NHAI Land Acquisition

The National Highways Act, 1956: Core Provisions

The National Highways Act, 1956, serves as the primary legislative instrument empowering NHAI to acquire land for highway development. Section 3A of the Act establishes the fundamental power of the Central Government to acquire land for public purposes. The section stipulates: “Where the Central Government is satisfied that for a public purpose any land is required for the building, maintenance, management or operation of a national highway or part thereof, it may, by notification in the Official Gazette, declare its intention to acquire such land” [4].

The procedural framework under the National Highways Act follows a structured approach beginning with the issuance of a notification under Section 3A. This notification must provide a brief description of the land proposed for acquisition and requires publication in two local newspapers, one of which must be in the vernacular language. The competent authority bears the responsibility of ensuring widespread dissemination of acquisition intentions, thereby fulfilling the constitutional mandate of due process.

Section 3B of the Act grants extensive survey powers to authorized personnel, including the authority to conduct inspections, measurements, valuations, and enquiries. These provisions enable NHAI representatives to “make any inspection, survey, measurement, valuation or enquiry; take levels; dig or bore into sub-soil; set out boundaries and intended lines of work; mark such levels, boundaries and lines placing marks and cutting trenches” [5]. Such comprehensive survey powers are essential for accurate project planning and land requirement assessment.

The objection mechanism under Section 3C provides affected landowners with the opportunity to challenge the proposed acquisition. Any person interested in the land may object within twenty-one days from the publication of the Section 3A notification. The competent authority must provide a fair hearing and may allow or disallow objections after due consideration. Significantly, Section 3C(3) declares that orders made by the competent authority under this provision are final, limiting further judicial review at this stage.

Section 3D establishes the declaration of acquisition procedure. Upon completion of the objection process, the competent authority submits a report to the Central Government, which then declares through Official Gazette notification that the land should be acquired. The Act provides that “on the publication of the declaration under sub-section (1), the land shall vest absolutely in the Central Government free from all encumbrances” [6]. This vesting provision represents a crucial aspect of the acquisition process, as it transfers ownership immediately upon publication, regardless of compensation payment status.

Compensation Determination Under the National Highways Act

Section 3G outlines the compensation determination mechanism, establishing a dual-track approach. The competent authority initially determines compensation amounts, but if either party finds the amount unacceptable, the matter proceeds to arbitration. The arbitrator, appointed by the Central Government, applies the provisions of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, to resolve disputes.

The factors for compensation determination under Section 3G(7) include: “(a) the market value of the land on the date of publication of the notification under section 3A; (b) the damage, if any, sustained by the person interested at the time of taking possession of the land, by reason of the severing of such land from other land; (c) the damage, if any, sustained by the person interested at the time of taking possession of the land, by reason of the acquisition injuriously affecting his other immovable property in any manner, or his earnings; (d) if, in consequences of the acquisition of the land, the person interested is compelled to change his residence or place of business, the reasonable expenses, if any, incidental to such change” [7]. These provisions make NHAI Land Acquisition a carefully regulated process that balances infrastructure needs with the rights of affected landowners

Integration with RFCTLARR Act, 2013

The relationship between the National Highways Act, 1956, and the RFCTLARR Act, 2013, represents one of the most complex aspects of NHAI land acquisition. Section 105 of the RFCTLARR Act initially excluded enactments specified in the Fourth Schedule, including the National Highways Act, from its application. However, subsequent amendments and judicial interpretations have significantly modified this position.

The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways issued comprehensive guidelines on December 28, 2017, clarifying the applicability of RFCTLARR Act provisions to National Highway acquisitions [8]. These guidelines, developed in consultation with the Attorney General of India, establish that compensation determination under highway acquisitions must follow the First Schedule of the RFCTLARR Act, even when the acquisition is conducted under the National Highways Act.

Judicial Developments and Case Law

Supreme Court Clarifications on Compensation

The Supreme Court’s decision in National Highways Authority of India vs. Sri P. Nagaraju (2022) provides crucial guidance on compensation determination under the National Highways Act [9]. The Court addressed the interaction between Section 3G(7)(a) of the National Highways Act and the RFCTLARR Act’s compensation provisions, particularly regarding the relevant date for market value determination.

The Court emphasized that Section 3G(7)(a) mandates consideration of “the market value of the land on the date of publication of the notification under section 3A.” However, the judgment also recognized the applicability of RFCTLARR Act’s First Schedule provisions through the notification dated August 28, 2015, which extended RFCTLARR Act benefits to acquisitions under enactments specified in the Fourth Schedule.

In Union of India & Anr. vs. Tarsem Singh & Ors., the Supreme Court addressed discrimination concerns arising from differential compensation structures between the National Highways Act and the Land Acquisition Act, 1894. The Court held that “non-grant of solatium and interest to lands acquired under the National Highways Act, 1956, which is available if lands are acquired under the Land Acquisition Act, is bad in law and violative of Article 14 of the Constitution of India” [10].

Procedural Clarity from Recent Judgments

The Supreme Court in Haryana State Industrial and Infrastructure Development Corporation vs. Deepak Aggarwal (2022) clarified the meaning of “initiation” under Section 24(1) of the RFCTLARR Act. The Court held that “land acquisition proceedings under the L.A. Act begin with the publication of a notification under sub-section (1) of Section 4” for the purposes of determining whether RFCTLARR Act compensation provisions apply to ongoing acquisitions [11].

This interpretation has significant implications for NHAI acquisitions initiated before January 1, 2014, but not completed by that date. Such acquisitions benefit from enhanced compensation under the RFCTLARR Act while following the streamlined procedures of the National Highways Act.

Right-of-Way Management and Regulatory Framework

Defining Right-of-Way Parameters

Right-of-way (ROW) management constitutes a critical component of NHAI’s operational mandate, encompassing not merely the carriageway but the entire corridor required for highway operations. Section 4 of the National Highways Act provides that national highways include “all lands appurtenant thereto, whether demarcated or not; all bridges, culverts, tunnels, causeways, carriageways and other structures constructed on or across such highways; and all fences, trees, posts and boundary, furlong and milestones of such highways or any land appurtenant to such highways” [12].

The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways has established detailed guidelines for ROW management, specifying minimum width requirements based on highway categories. Express highways require a minimum ROW of 60 meters, while four-lane highways need 45 meters, and two-lane highways require 30 meters. These specifications ensure adequate space for future expansion, utility corridors, and safety considerations.

Access Control and Encroachment Prevention

The Standing Committee on Transport, Tourism and Culture noted in its February 2024 report that “encroachment is a prominent reason for accidents on national highways” [13]. The Committee recommended implementing stricter penalties for encroachment violations and streamlining legal processes for swift resolution.

NHAI has responded to encroachment challenges through multiple initiatives. The authority conducts regular surveys using satellite imagery and GIS mapping to document unauthorized constructions within ROW limits. Legal proceedings under Section 8B of the National Highways Act enable prosecution of individuals causing mischief to national highways, with penalties including imprisonment up to five years.

The Ministry has also issued revised guidelines for access permission, establishing standardized procedures for legitimate access to national highways while preventing unauthorized entry points that compromise traffic flow and safety.

Infrastructure Development and Maintenance Obligations

Statutory Responsibilities Under Section 5

Section 5 of the National Highways Act places the responsibility for highway development and maintenance squarely on the Central Government. The provision states: “It shall be the responsibility of the Central Government to develop and maintain in proper repair all national highways” [14]. However, the section also permits delegation of these functions to state governments or subordinate authorities under specified conditions.

NHAI’s role as the implementing agency for highway development has evolved significantly since its establishment. The authority now manages construction contracts worth thousands of crores, oversees public-private partnerships, and ensures compliance with environmental and safety standards across its extensive network.

Funding Mechanisms and Financial Framework

The Union Budget allocated ₹1.68 lakh crore to NHAI for the financial year 2024-25, representing a substantial commitment to highway infrastructure development [15]. This allocation supports various funding mechanisms including:

Direct budgetary support for critical projects requiring government intervention Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) models enabling private sector participation Hybrid Annuity Model (HAM) combining government and private funding Infrastructure Investment Trusts (InvITs) for asset monetization

The National Highways Fee (Determination of Rates and Collection) Rules authorize NHAI to collect tolls and fees for services rendered on national highways. Section 7 of the National Highways Act provides the legal foundation for fee collection, while Section 8A enables agreements with private entities for highway development and maintenance in exchange for toll collection rights.

Environmental and Social Compliance

NHAI’s infrastructure development activities are subject to comprehensive environmental and social compliance requirements. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification, 2006, mandates environmental clearance for highway projects exceeding specified thresholds. Projects requiring land acquisition above certain limits must also obtain forest clearance under the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980.

The RFCTLARR Act’s Second and Third Schedules, applicable to NHAI acquisitions through the 2015 notification, establish detailed rehabilitation and resettlement obligations. These include providing replacement land, housing assistance, employment opportunities, and infrastructure development in affected areas.

Regulatory Challenges and Operational Issues

Land Acquisition Delays and Cost Escalation

The Standing Committee on Transport, Tourism and Culture observed that “tenders worth Rs 50,000 crore invited by NHAI are pending for 9-14 months” due to land acquisition challenges [16]. The Committee recommended that “at least 95% of continuous land stretch should be acquired and possessed at the time of bidding, to avoid delays.”

Land acquisition delays stem from multiple factors including complex legal procedures, disputes over compensation, environmental clearances, and local resistance. The requirement for multiple approvals from different authorities creates coordination challenges that can extend project timelines significantly.

Recent data indicates that highway project awards from April 2023 to November 2023 amounted to only 2,815 kilometers, approximately half the projects awarded during the same period in the preceding fiscal year. This decline reflects the ongoing challenges in land acquisition and ROW procurement.

Technological Solutions and Digital Initiatives

NHAI has embraced technological solutions to address operational challenges. The BhoomiRashi portal, launched on April 1, 2018, streamlines the land acquisition process by providing simultaneous Hindi translation, linking to e-gazette for expeditious publication, and offering predefined formats for notifications [17].

The portal includes an award calculator for error-free compensation determination and has processed 8,629 land acquisition notifications since its launch. Nearly 11,70,000 people have visited the portal, demonstrating its effectiveness in improving transparency and accessibility.

The “Harit Path” mobile application enables monitoring of plantations along national highways, supporting NHAI’s environmental commitments. This digital infrastructure represents a significant advancement in project management and stakeholder engagement.

Future Directions and Policy Considerations

Integration of Green Highway Initiatives

NHAI’s Green Highways Division has been entrusted with planning, implementation, and monitoring of roadside plantations along one lakh kilometers of national highways. This initiative aims to generate one lakh direct employment opportunities in the plantation sector over ten years while enhancing environmental sustainability.

The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways launched the green highways program in 2016, emphasizing the integration of environmental considerations into highway development. Future policy directions likely will emphasize climate resilience, carbon neutrality, and ecosystem preservation.

Technological Innovation and Smart Infrastructure

The memorandum of understanding between NHAI and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) for satellite mapping of highways represents a significant step toward smart infrastructure development. Future initiatives may include intelligent transportation systems, automated toll collection, and real-time traffic management.

The government’s emphasis on securitized green bonds for BOT projects may provide sustainable financing mechanisms while promoting environmentally responsible development. These financial innovations could ease funding requirements for both NHAI and private concessionaires.

Legislative and Regulatory Reforms

The May 15, 2024 circular issued by the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways regarding RFCTLARR Act applicability reflects ongoing efforts to clarify legal frameworks [18]. Future reforms may focus on streamlining procedures, reducing approval timelines, and enhancing coordination between different regulatory authorities.

The integration of digital processes, standardized procedures, and transparent mechanisms will likely continue evolving to meet the challenges of large-scale infrastructure development while ensuring compliance with constitutional and statutory requirements.

Conclusion

NHAI Land Acquisition represents a complex intersection of statutory authority, constitutional obligations, and practical challenges in infrastructure development. The evolution of legal frameworks, particularly the integration of RFCTLARR Act provisions with National Highways Act procedures, demonstrates the dynamic nature of land acquisition law in India.

The success of NHAI’s mandate depends critically on effective coordination between legal compliance, community engagement, environmental protection, and operational efficiency. Recent technological initiatives and policy reforms indicate a positive trajectory toward more transparent, efficient, and sustainable highway development.

Future developments in NHAI land acquisition and management will likely emphasize digital transformation, environmental sustainability, and enhanced stakeholder participation while maintaining the constitutional imperatives of due process and fair compensation. The authority’s ability to adapt to these evolving requirements will determine its effectiveness in delivering India’s ambitious highway infrastructure goals.

The comprehensive legal framework governing NHAI’s operations, supported by evolving judicial interpretations and technological innovations, provides a robust foundation for addressing the complex challenges of modern highway development. Continued refinement of these systems will be essential for meeting India’s growing transportation needs while protecting the rights and interests of affected communities.

References

[1] Vajira Mandravi. “National Highways Authority of India.” Current Affairs, 2024. Available at: https://vajiramandravi.com/current-affairs/national-highways-authority-of-india/

[2] Ministry of Road Transport & Highways. “Land Acquisition.” Government of India. Available at: https://morth.nic.in/land-acquisition

[3] SCC Times. “Income Tax on Compulsory Acquisition Under the NHAI Act.” SCC Times, February 6, 2024. Available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2024/05/10/income-tax-on-compulsory-acquisition-under-the-nhai-act/

[4] India Code. “The National Highways Act, 1956.” Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1651/1/AAA1956____48.pdf

[5] Indian Kanoon. “Section 3A in The National Highways Act, 1956.” Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/160012649/

[6] Indian Kanoon. “Section 3D in The National Highways Act, 1956.” Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/2070234/

[7] Indian Kanoon. “The National Highways Act, 1956.” Available at: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1222415/

[8] Fox Mandal. “NHAI issues Circular on Land Acquisition Laws.” June 8, 2024. Available at: https://www.foxmandal.in/News/nhai-issues-circular-on-land-acquisition-laws/

[9] Legal Research Wing. “Supreme Court clarifies land compensation under National Highways Act: NHAI vs. Nagaraju (2022).” July 11, 2022. Available at: https://research.grhari.com/supreme-court-clarifies-land-compensation-under-national-highways-act-national-highways-authority-of-india-vs-sri-p-nagaraju-2022/

[10] IBC Laws. “Union of India & Anr. Vs. Tarsem Singh & Ors. – Supreme Court.” Available at: https://ibclaw.in/union-of-india-anr-vs-tarsem-singh-ors-supreme-court/

[11] LiveLaw. “Sec 24(1) RFCTLARR Act- Land Acquisition Proceedings Get ‘Initiated’ From Publication Of Sec 4(1) Notification Under 1894 Act: Supreme Court.” July 31, 2022. Available at: https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/supreme-court-rfctlarr-initiation-issuance-publication-land-acquisition-haryana-state-industrial-and-infrastructure-development-corporation-vs-deepak-aggarwal-2022-livelaw-sc-644-205255